Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall has hinted at the existence of a new intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) platform, something that has long been a topic of discussion around the future of U.S. Air Force capabilities. Frequently, such a platform has been understood as a very stealthy, long-range, high-altitude surveillance drone commonly referred to as the RQ-180, although there are other possibilities, too, and even an RQ-180 would only be one facet in a larger constellation of next-generation ISR systems.

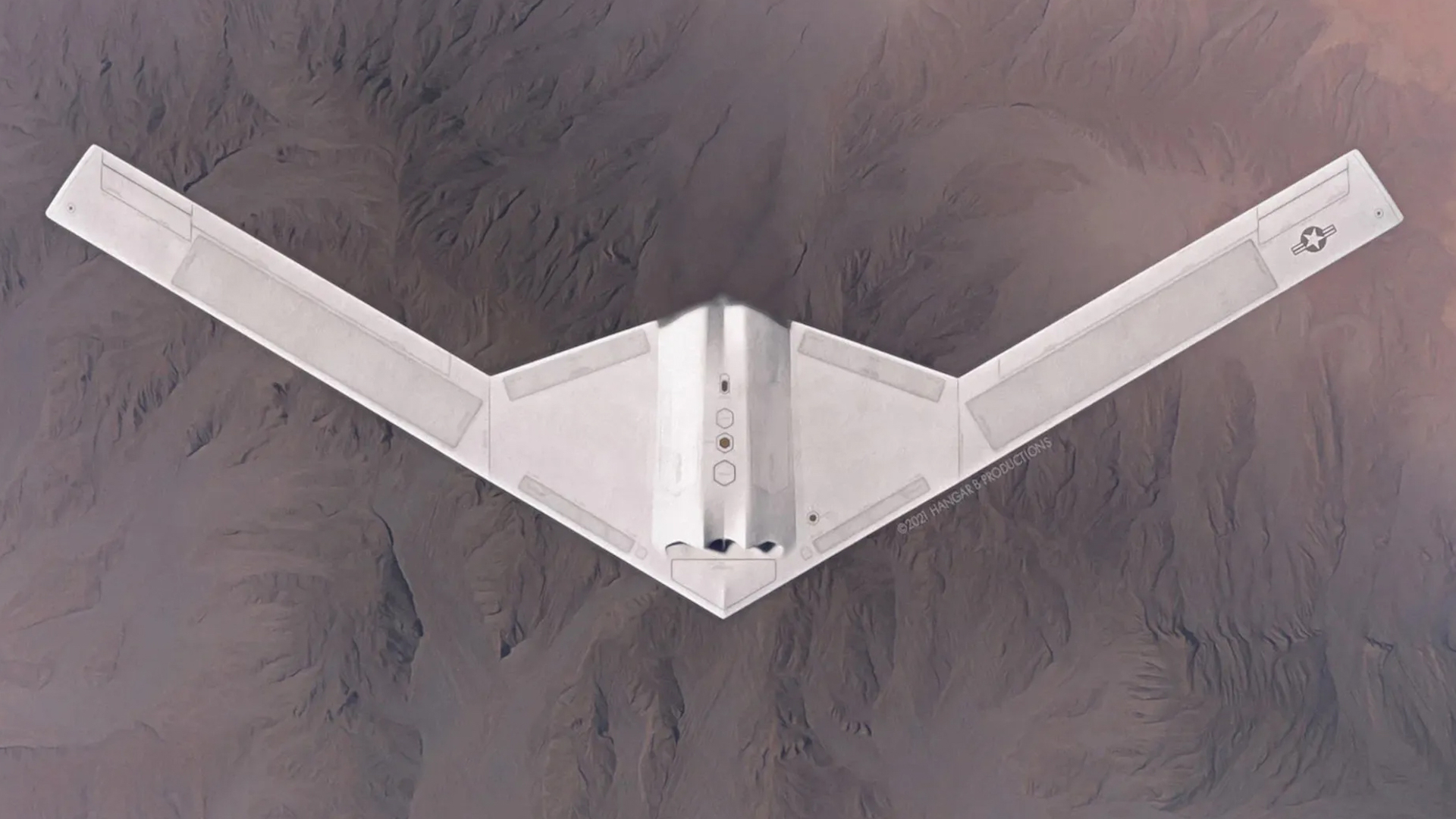

A notional rendering of what the high- and long-flying RQ-180 stealth drone might look like appears at the top of this story. While it has been widely posited that the RQ-180, or at least progenitors of it, have been flying for years and may be operational at least in small numbers and to a limited degree, there is no guarantee that such a system continues to receive the Air Force’s backing. This is especially true as space-based distributed constellations are quickly gaining favor throughout the DoD. These are highly resilient to attacks and offer persistent surveillance of target areas that was unheard of in past low earth orbit-based sensing systems. In fact, one program for this kind of capability is deep in development now and it appears aimed at doing at least part of what a notional RQ-180 would likely be tasked with doing. In other words, just because an RQ-180-like aircraft exists, it doesn’t mean its future is guaranteed.

Speaking at a roundtable event on Sunday, just before the opening of the Farnborough International Airshow in England, Kendall was responding to a question from Chris Pocock, a long-time aviation journalist, author, and expert on the U-2 Dragon Lady spy plane. Pocock was asking the Air Force chief about plans for the airborne ISR layer once the U-2 Dragon Lady and RQ-4 Global Hawk are withdrawn — moves that will follow the previous retirement of the E-8C Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System (JSTARS).

“What is that airborne layer? You’re retiring JSTARS, you’re retiring the U-2, you’re retiring Global Hawk,” Pocock said.

Kendall’s response was intriguing, describing that future ISR layer as “a combination of things.”

“I mentioned E-7 at the beginning of the conversation,” Kendall continued. “That’s part of that layer. So, we’re making progress on that, as I said before. We’re retaining some of the [E-3 Sentry] AWACSs, for example, to help transition smoothly over to a combination of … space-based capabilities and new systems like the E-7. So there’s a mix of systems in there, some of which there’s not much I can say about them.”

At least one of the systems that the Secretary of the Air Force cannot say much about is likely the aforementioned ‘RQ-180.’

Of course, as we’ve discussed in the past, various tiers of uncrewed ISR aircraft are in development in the classified and unclassified realm, or even possibly already in limited service, to help meet the USAF’s requirements. Also distributing these tasks to multiple desperate aircraft, including multi-role manned and unmanned types, and fusing the data they collect via advanced networking is also clearly a part of this solution. As Kendall mentioned and as we detailed at the top of this article, the Air Force is also busily working on new distributed ISR satellite constellations.

Still, no matter how advanced these satellite constellations are, they will still lack some of the versatility and flexibility that platforms operating in the earth’s atmosphere, uncrewed or otherwise, can provide. There is also a need for redundancy when it comes to gathering this critical information. While it appears the USAF is stepping backwards in terms of visible platforms available for gathering key battlefield and general intelligence data over large areas, the need for this data has only grown exponentially, and that is certainly recognized by USAF planners.

What Kendall’s statement underlines is that there is not a one-size-fits-all replacement, or single platform that will supersede the capabilities currently provided by the U-2, RQ-4, and E-8C. The end result is certain to focus on distributed concepts, both terrestrial and in space, that will collectively leverage advanced computing and networking architectures to not only collect huge amounts of data but to prioritize the parts of that data that actually matter so it can best be exploited it in near real-time.

The Air Force’s current plan is to divest the last of the U-2s in 2026, although members of Congress are attempting to prevent the service from retiring its fleet of these high-flying Cold War-era jets.

The Air Force is also planning to retire its remaining RQ-4 high-altitude, long-endurance drones by the end of the 2027 Fiscal Year.

Already retired is the E-8C, which completed its final operational deployment in June last year and was finally retired last November.

In the past, the withdrawal of the U-2 and RQ-4 have been seen as likely evidence that the Air Force has a suitable uncrewed replacement getting close to entering service, or perhaps even being employed operationally on some level.

It’s notable, too, that earlier legislation had included a path to proceeding with retiring the U-2 only if the Pentagon could certify that certain stipulations had been met. This included the insistence that the resulting capability gap would be filled in a cost-effective manner, something you can read more about here.

A major argument in favor of retiring both the U-2 and the RQ-4 is these platforms’ increasing vulnerability to air defenses, even those now fielded by lower-tier potential adversaries. In the case of facing off against near-peer competitors like China and Russia, the survivability of the U-2 and the RQ-4 is extremely questionable, with even just the ability to get close enough to bring their sensors to bear now being deeply challenged. In the case of China, especially, the threat is only growing, as its military continues to expand its anti-access and area denial bubbles and extend these ever further from the mainland.

When news of the plan to retire the last of the RQ-4 emerged, in July 2022, Ann Stefanek, an Air Force spokesperson, told Breaking Defense:

“Our ability to win future high-end conflicts requires accelerating investment in connected, survivable platforms and accepting short-term risks by divesting legacy ISR assets that offer limited capability against peer and near-peer threats.”

A very public demonstration of the RQ-4’s vulnerability came in June 2019, when a BAMS-D drone — a U.S. Navy variant of the Global Hawk — was shot down by Iran over the Persian Gulf. There followed a very public discussion about the utility of the Global Hawk family in future higher-end conflicts against opponents with more robust air defense networks.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that the sensor capabilities of the U-2 and the RQ-4 are still very valuable.

These high-flying ISR platforms can carry an extensive array of different imaging, signals intelligence, radar, and other sensors simultaneously. Unlike space-based assets, U-2s and RQ-4s can and do regularly deploy to different forward locations, from where they offer a uniquely flexible and unpredictable intelligence-gathering capability, able to quickly orbit over a particular area of interest for extended periods of time.

With this in mind, it’s generally accepted that one critical part of the Air Force’s new-look airborne ISR layer will be a long-range, high-altitude spy drone that is also stealthy, meaning it’s able to penetrate the kinds of air defenses within which a U-2 or RQ-4 wouldn’t be able to safely operate, despite the long reach of their sensors. Once there, it will be able to persist for long periods of time, sucking up critical intelligence while the enemy doesn’t even know anyone is looking.

In fact, Kendall’s reference at the weekend is only the latest clue pointing to the existence of a platform the existence of which makes sense for the Pentagon. In addition to this primary role, the RQ-180, or variants of it, could also serve as an electronic attack and communications and data-sharing node, too. This is all based on the understanding that a stealthy high-end drone of this kind would secure the funding that it needs, something that is becoming more questionable as the Air Force starts to look at ways of driving down the costs of big-ticket programs such as the crewed fighter at the heart of its Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) initiative.

While still guarded, the Secretary of the Air Force’s recent words do underline the understanding that legacy ISR platforms, once considered irreplaceable to operations, are now judged too vulnerable to survive.

As these legacy platforms continue to be phased out, the Air Force is obviously investing in more modern and survivable systems. At this point, we still don’t know if the RQ-180 will end up being one of those systems, and in what capacity, but Kendall’s statement certainly appears to add credence to claims of its existence.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com