Days after announcing it had completed testing of its new-generation XA100 engine under the Adaptive Engine Transition Program, or AETP, General Electric confirmed to The War Zone that it is now looking at inserting that same potentially revolutionary technology into the short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) F-35B stealth fighter. Previously, the XA100 was being tailored only as an option for the conventional takeoff and landing F-35A and the U.S. Navy’s F-35C carrier variant. Meanwhile, the AETP effort is also serving as a stepping stone toward future powerplants for the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) family of systems and beyond.

Speaking to The War Zone, David Tweedie, GE Edison Works’ vice president and general manager for Advanced Products, confirmed that, “within the last few weeks,” the company has concluded a technical integration study looking at what it would take to modify the XA100 and integrate it with the F-35B. The company has assessed how the F-35B’s performance would be improved as a result, but is remaining tight-lipped about this and the wider requirements that drove the study.

“I am happy to report that we were able to show a technical solution there that did meet the technical goals that were put out and it was a very collaborative and productive effort, with both Lockheed Martin and the Joint Program Office,” Tweedie said. “Now, the B-model user community will have options for multiple engine companies moving forward as they think about their modernization needs, which is something they have never had.”

Designed for the F-35A and C, with the aim of having “100 percent part-number commonality” across those two variants, the XA100 is one of two engines that have been developed under the AETP effort, launched in 2016, the other being the rival XA101 from Pratt & Whitney. Currently, all three versions of the F-35 are powered by the Pratt & Whitney F135 turbofan. Work on an alternative engine, the F136 from GE and Rolls-Royce, was controversially canceled in 2011 after reaching relative maturity after years of work and billions of dollars spent.

AETP is already being billed as the next big thing in /.fighter aircraft propulsion. For GE, the XA100 represents the “third revolution” in this field, after the switch from piston engines to single-stream turbojets in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and then the introduction of two-stream, mixed-flow turbofans in the 1970s that accompanied the arrival of what are now termed fourth-generation fighters.

While scaled to be installed in the F-35 in the first instance, GE’s XA100 aims to pioneer a broader set of technologies that will provide a leap in performance for both fifth- and sixth-generation fighters.

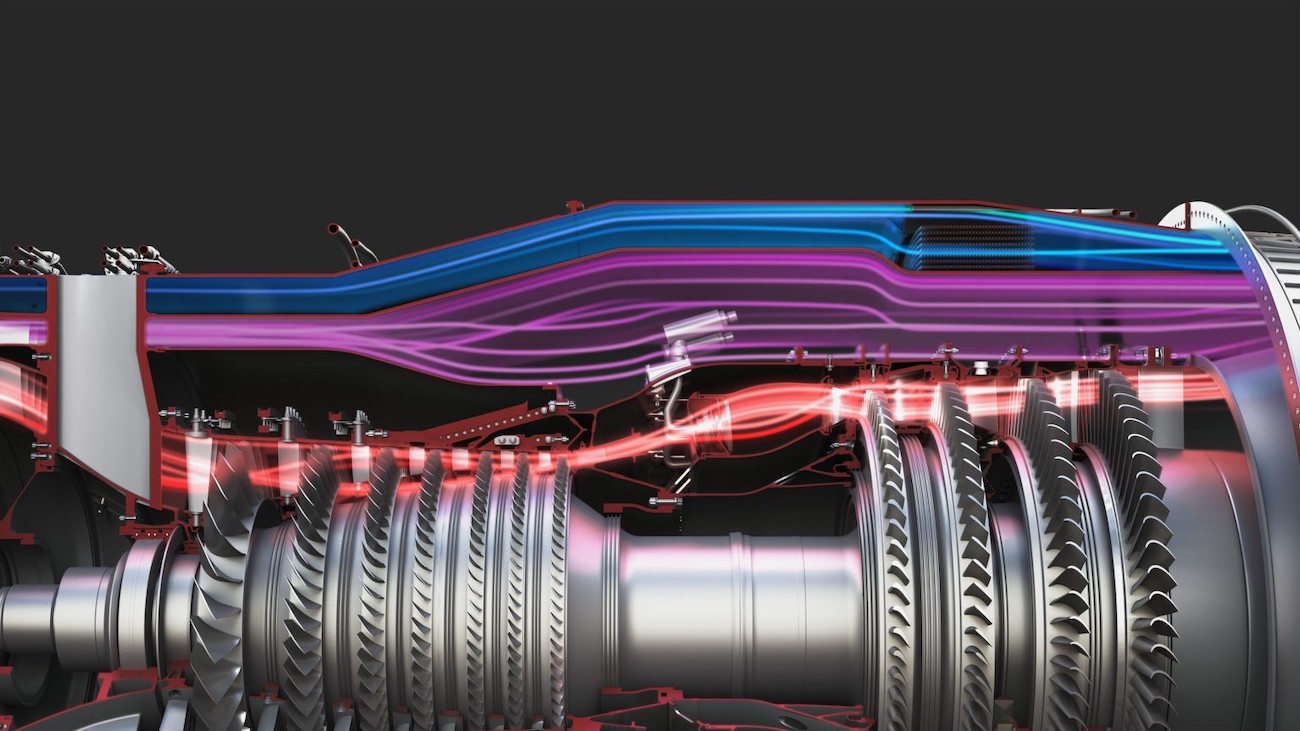

To achieve this, the XA100 relies on three fundamental new innovations.

First, it uses an adaptive cycle engine. This allows a single powerplant to harness the advantages offered by traditional commercial mixed-flow turbofans — primarily subsonic fuel efficiency — as well as the benefits of typical two-stream fighter engines: high speed, rapid acceleration, and generous thrust-to-weight performance.

As Tweedie explained, an adaptive cycle engine like the XA100 provides the best of both worlds: “An engine that can be reconfigured in flight, adjust its bypass ratio to operate more like a commercial engine in a fuel-efficient mode, in subsonic cruise and loiter conditions, but then still have the ability to flex into a more traditional high-thrust mode for combat acceleration, high-Mach performance.”

Second, the XA100 is based around a three-stream architecture. “That third stream is primarily there to serve as a thermal management heat sink,” Tweedie said. This requirement is primarily driven by the exponential growth in thermal management demands for fifth- and sixth-generation fighters. Increasingly, it will be a challenge to service the thermal demands of advanced new mission systems and potentially even directed-energy weapons.

The third and final innovation concerns advanced materials and manufacturing techniques. For GE, this has involved transitioning its hot section flow-path components from the nickel-based superalloys that have been standard for decades, to ceramic-based materials. “We initiated that in our commercial world, now we’re taking it to the next level in our military space,” Tweedie outlined. “Those materials can run hotter and that’s how you get more performance; they’re lighter, and even at those hotter temperatures, they’re significantly more durable. So you move the curve on both performance and durability, which is unusual.”

New manufacturing techniques include additive manufacturing, also referred to as 3D printing. Tweedie explained that a “significant portion” of the XA100 is manufactured additively, including certain components that couldn’t be made using traditional manufacturing techniques.

Putting these three things together has reportedly yielded impressive results in the XA100. In terms of performance, compared with traditional engines like the F135 used in the F-35, the XA100 is said to be 25 percent more fuel efficient, offers between 10 and 20 percent more thrust at different points of the flight envelope, provides double the thermal management, and meets or exceeds current durability requirements. These figures match the goals that the Air Force has set out publicly in the past for the AEPT effort. Installing an XA100 in an F-35A should translate to 30 percent more range and acceleration increased by more than 20 percent.

The durability point, especially, has resonance for the Joint Strike Fighter program, which has had a number of engine-related issues through the years. Things reached a particularly low point last year when a full 15 percent of U.S. Air Force F-35As were without functioning engines due to excessive wear on their turbine rotor blades. In recent months, The War Zone has reported on how the F-35 continues to be plagued by a lack of parts for its F135 engines, as well as the people and places to fix them.

Clearly, the Air Force sees the potential in the new XA100 and XA101 and has, according to GE, invested over $4.4 billion in new fighter engine technologies since 2007, including under AETP.

Since the engine fit requirements of the F-35A and the F-35C are very similar, the XA100 has always been intended for the carrier variant as well, although it’s being run as an Air Force program. The Air Force “fully supported” this approach, Tweedie confirmed.

The three main factors to consider in ensuring the XA100 is also suitable for the F-35C are the marinization of certain components to ensure they function as advertised in a shipborne environment, maintenance requirements that are compatible with the more limited facilities available on the ship, and compatibility with the larger tailhook on the F-35C, which provides certain physical constraints.

The result, in Tweedie’s words, is an engine that “can seamlessly fit in the F-35C and we will have a 100 percent part-number common solution between the F-35A and the C. And I think that’s unique within the two competitors that are playing in this space.”

Now, GE is looking beyond the F-35A and C toward the F-35B, where the integration challenge is significantly greater. After all, the STOVL version’s powerplant arrangement adds a lift fan at the front, roll posts on the side, and a swiveling exhaust nozzle at the back. “You’ve got to physically integrate with all those things, that’s the challenge the B provides,” Tweedie remarked.

In fact, such were the challenges involved that integrating the XA100 on the F-35B was initially judged beyond the scope of GE’s activities. Things changed roughly a year ago when, in Tweedie’s words, “We reached the point where we had a good XA100 design, we know what we’ve got, we had a little bit of bandwidth and some customer requests from the Joint Program Office.”

While recognizing that the baseline XA100 would not fit in the F-35B ‘as is,’ the question became one of assessing what additional and unique efforts would be needed to integrate it with the F-35B — and what capabilities they would end up with. What GE found was a viable path to bring the XA100, or a variant of it, to the F-35B.

Tweedie confirmed that the company’s analysis showed that the new engine for the F-35B “meet the goals that the B-model community has thrown out there for improvements they would like.” Since these requirements have not been made public, GE is not at liberty to divulge them. But it might well be assumed that the Marine Corps, Joint Program Office, Lockheed Martin, and potentially also other F-35B operators share the Air Force’s desire for more power, range, fuel efficiency, and reliability. All these factors are likely to be increasing demand in a potential conflict with China in the Asia Pacific region — something that some military leaders could happen sooner rather than later.

However, there are some different requirements, too, and not just in terms of STOVL propulsion configuration. “The B-model user community as part of this study did articulate their own look at propulsion improvements they’d like to see to meet their emerging needs, and they’re not identical [to the Air Force],” Tweedie said.

The issue of range is certainly one that has specific importance to the kinds of missions envisioned in Asia Pacific contingencies and it has a particular bearing on the F-35B, which has the smallest fuel load of the three variants: 13,500 pounds compared to around 18,500 pounds for the F-35A, and 19,750 pounds for the F-35C. That results in a combat radius of 400 nautical miles for the F-35B, while the equivalent figure for the F-35C is 675 nautical miles. In its latest Aviation Plan, the Marine Corps identified external fuel tanks as one part of the modernization plan for the F-35B, but does not mention re-engining.

What we know for certain is that undisclosed F-35B operators have shared with GE the performance improvement goals that they want to see in the jet, and the company has, within the last few weeks, determined that its engine can meet them. Tweedie also noted that Rolls-Royce, responsible for the F-35B’s lift fan, was a participant in the latest study.

For the time being, XA100 remains an Air Force initiative, although there are clearly encouraging signs for GE that the Navy and Marine Corps might also want to leverage the additional performance it can offer all F-35 variants.

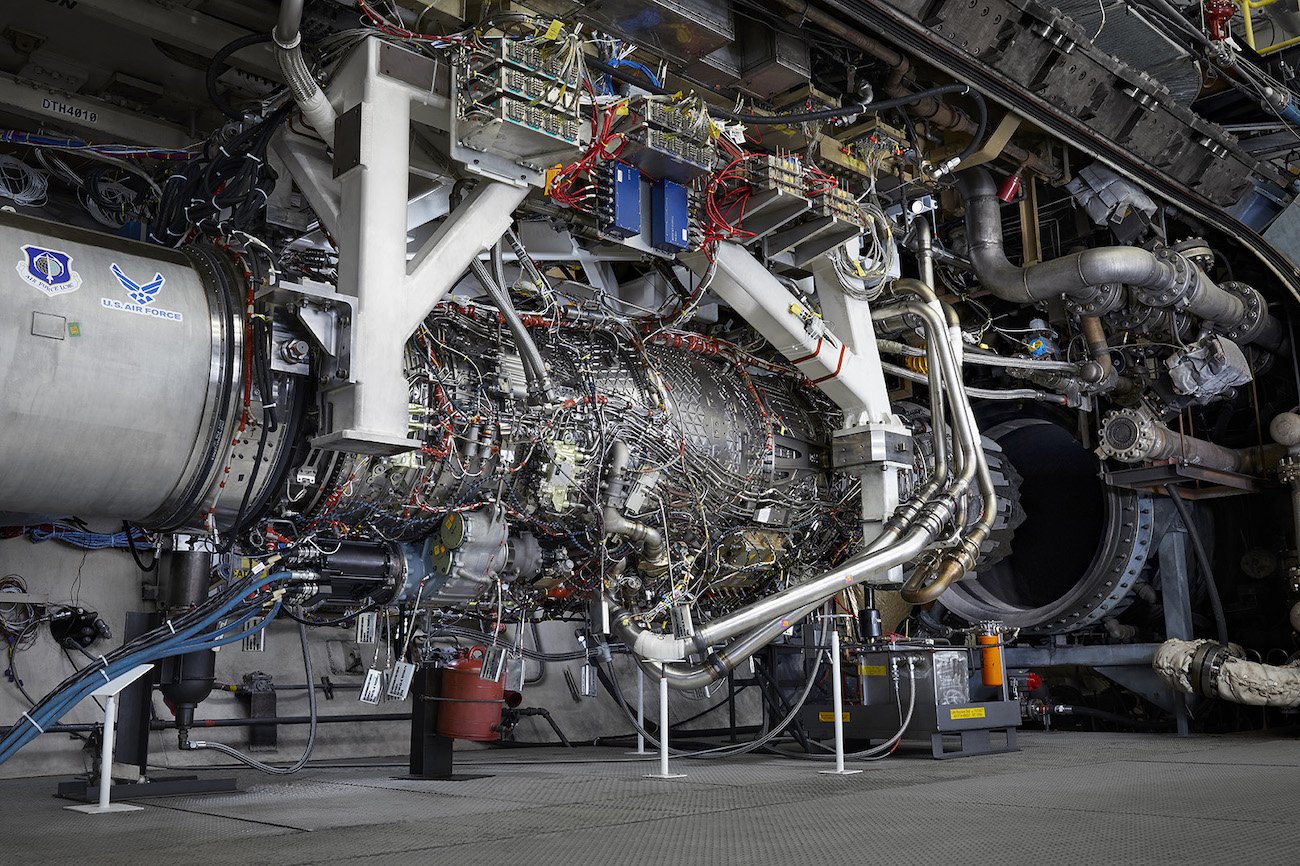

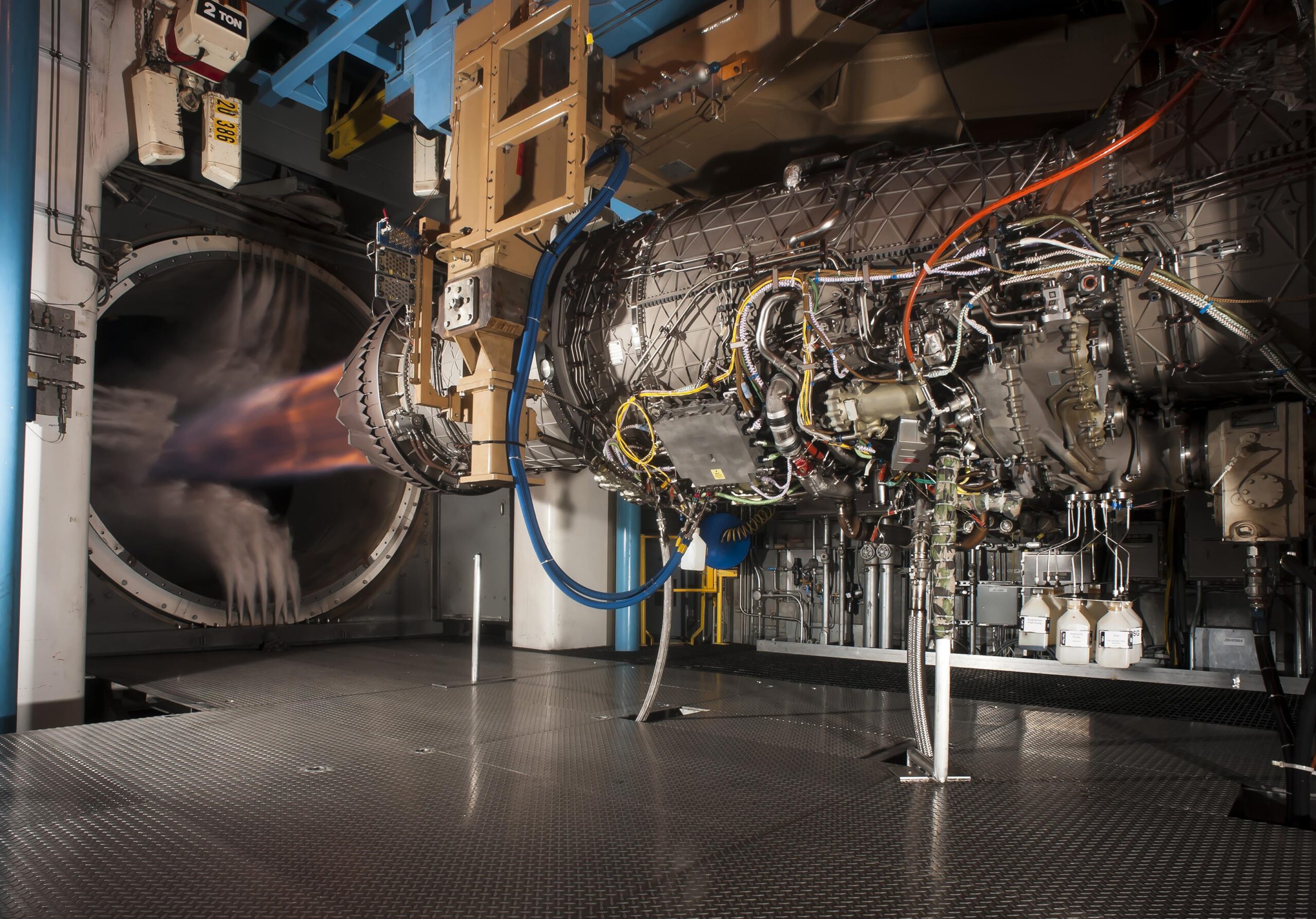

In the meantime, the company recently announced that it had wrapped up the second and final phase of XA100 testing under the AETP initiative, marking the final major contract milestone of the program.

This effort has been pursued under an aggressive schedule, which aims to have a next-generation engine for the F-35A ready for production before the end of the decade, providing the project continues to find support.

Tweedie explained the significance of this testing milestone: “We have now demonstrated in a flight-ready full-up systems demonstration, across the simulated flight envelope, at the Arnold Engineering Development Complex, that this technology works, it’s mature and it’s ready for low-risk EMD manufacturing and development programs, which is the whole goal of this multi-year opportunity.”

So far, the Air Force has supported the F-35A re-engining initiative, with Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall being a particular proponent of the effort.

GE is hopeful now that Kendall’s announced desire that a decision be made on F-35A re-engining in the fiscal year 2024 budget cycle comes to pass. “Those deliberations we believe are happening as we speak,” Tweedie explained. “We think it’s very critical that the time is now to make a decision to bring this capability to the F-35.”

Therefore, next February could bring confirmation of where this effort goes next, and to what degree GE will be involved in it.

“We’re certainly hopeful that there is an EMD program start laid into the fiscal 2024 budget,” Tweedie added. “The Air Force has set a target and we think we can meet a fiscal 2028 initial service release and qualification of the vehicle.”

Should the XA100 be selected for the F-35A, GE says that it could be introduced to the production line as part of a block upgrade, or it could be retrofitted to existing aircraft with the original F135 engine. “I think there’s a lot of different options that are under consideration,” Tweedie noted. “What we have done is design this for seamless integration into the F-35 jet. So, certainly, the block upgrade introduction could be done seamlessly. We also believe that retrofits could be done pretty affordably with very minimal changes, if any, to the aircraft. We really see this as both forward compatible and backward compatible and that’s an option for the Air Force, the Navy, and all the partners and FMS customers who’ve already procured a number of assets. We think that both are economically viable and certainly technically viable.”

On the other hand, there is still the option that the Pentagon will opt for a more modest approach to re-engining the F-35, with the F135 Enhanced Engine Package, an update of the existing powerplant that is being offered by Pratt & Whitney. It may even decide to stick with the baseline F135 and invest funds to modernize other aspects of the Joint Strike Fighter, but this seems less likely, bearing in mind Joint Program Office officials’ previous statements.

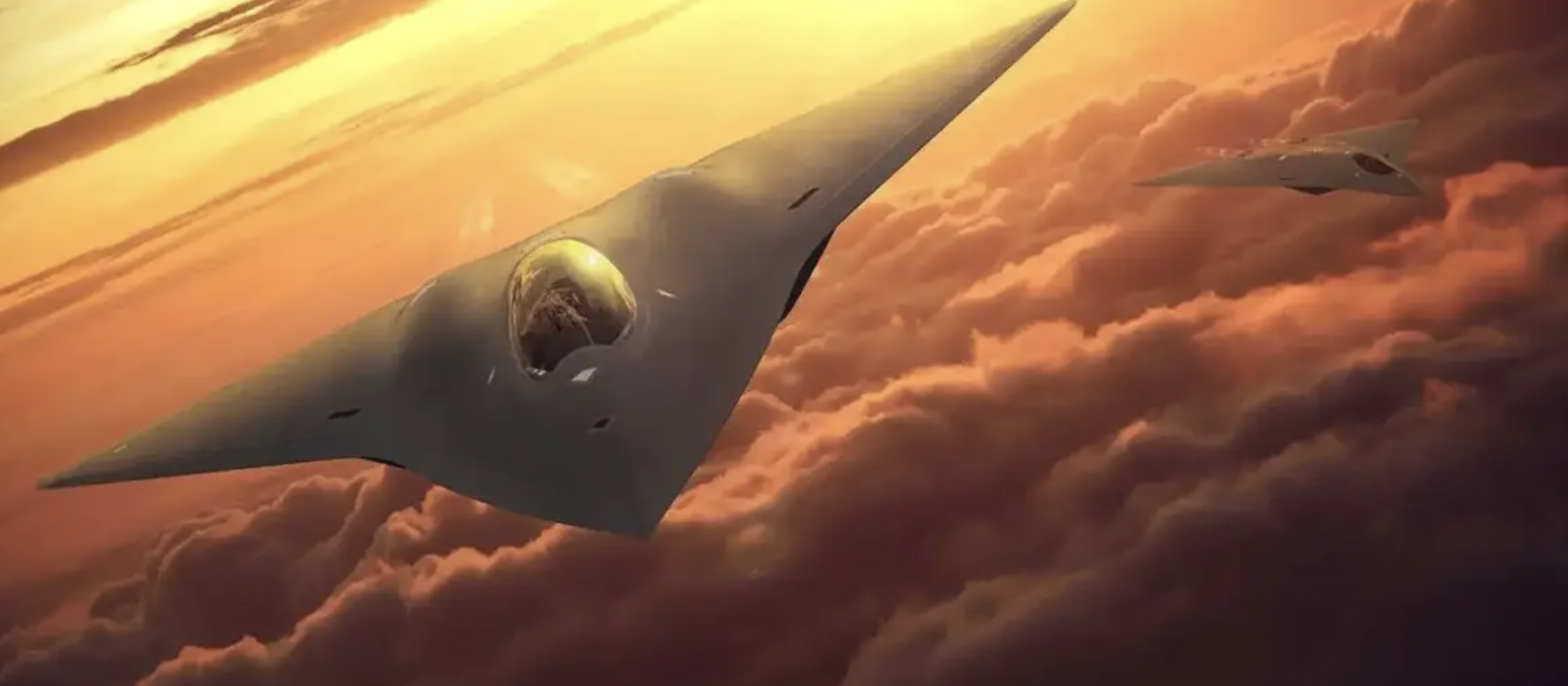

Then, beyond the F-35, the XA100 developed most recently under AETP, is also feeding into a next-generation propulsion effort for the NGAD family of systems. Details of this effort, known as the Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion program, or NGAP, are sparse, befitting the secretive nature of the wider NGAD initiative. However, we do know that the Air Force has awarded large potential contracts to both engine companies (GE and Pratt & Whitney) and three “weapons systems contractors” — the established airframers Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman. Under this arrangement, GE explained, the engine companies will tailor propulsion system designs for a “variety of airframe concepts” produced by the three airframers.

Tweedie describes NGAP as “a parallel and related effort” to AETP, and that it will result in engines that “are unique in size and configuration and optimized for the NGAD family of systems” in the same way that the AETP engines, GE’s XA100 and Pratt & Whitney’s XA101, are sized and optimized specifically for the F-35.

Another XA100 spinoff could see the engine, or, more likely, technologies that it’s proven out, being used to re-engine ‘legacy’ fighters, too. While Tweedie reiterated that “direct transition to the F-35 was always the prime path,” he also noted that “there was a look at whether you can spin upgrades back into propulsion systems, perhaps to power F-15s and F-16s, as an example.” He confirmed that GE continues to work with the Air Force on looking at opportunities of this kind, but that they only make sense if the investment-versus-capability equation adds up.

With its XA100, GE is seeking to do nothing less than transform the fighter aircraft propulsion industry. Exactly how that plan develops remains to be seen, although the fact that all three F-35 variants are now being considered for re-engining only reinforces the fact that the XA100 is very much designed around the Joint Strike Fighter. But at the same time, the XA100, however it fares with the F-35 program, seems to be already feeding valuable information into future air combat systems. As such, it could well prove to be a cornerstone in the continued evolution of U.S. airpower.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com