During the dawn of aerial combat in World War I, flyers came up with inventive ways of practicing using their aircraft-mounted machine guns. The image above is a case in point. Taken on July 17, 1918, it depicts a Royal Air Force (RAF) Pilot Officer conducting target practice from a moving ‘cockpit’ as it hurtles around a curved track at the RAF’s Rang-du-Fliers gunnery school at Berck in northern France.

At this late stage of the war, the RAF was actually still an extremely new branch of the British military. Formally activated on April 1, 1918, it was born from a merger of the British Army’s Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Navy’s Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), which had together served as Britain’s air forces up to this point during the war. In many ways, the image at the top of this story highlights the rapid transformation of airpower during the war, and the technological advances which accompanied this, especially through the addition of machine guns to airplanes. Aerial gunnery was an entirely new aspect of warfare born of World War I, which demanded that flyers engage adversaries in three dimensional combat.

During World War I, the use of airpower was closely linked with the collection of intelligence. Flying high above the battlefield dominated by enemy trenches, early wartime aircraft like the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 (a single-engine biplane) performed reconnaissance missions that helped keep commanders abreast of enemy maneuvers on the ground. These early aircraft featured wooden-framed fuselages, with wooden main spars and ribs on their wings. By the end of August 1914, airplane reconnaissance was the primary means by which armies received operational information. These reconnaissance missions were enhanced in early 1915 with the introduction of cameras fitted to aircraft.

Pilots and observers often carried basic weapons on reconnaissance missions in the early stages of the war, including handguns for use against enemy aircrews. This was hugely impractical, however, and as airplane technologies developed the need for fighter (as well as bomber) aircraft arose. From 1915, German fighters began brandishing forward-facing machine guns, thanks to the Dutch aircraft manufacturer Anthony Fokker’s perfection of an existing French invention that allowed bullets to be fired through airplanes’ moving propellers. British and French fighters soon followed.

Biplane designs continued to be produced as the best compromise between speed and maneuverability, but aircraft fuselages were streamlined and covered in fabric. At first, fighters typically performed ‘lone wolf’ missions, but it quickly became apparent that flying in pairs or groups was more effective at providing reconnaissance support — thus the notions of mutual observation, firepower, and support grew.

In 1916, with German fighter aircraft dominating the skies into the spring of that year, British pilot and observer training shifted to reflect the growing need for aircraft machine gun training. Although reconnaissance training was still the top priority, new pilots — instructed at various RFC and RNAS training schools across the United Kingdom — were expected to undergo three to six hours of practical instruction on machine gun use.

With the majority of pilots and observers being trained in the United Kingdom, and with those personnel receiving superior training to men in France, it was decided that improvements should be made to field training in order to provide men the opportunity to further practice firing machine guns in simulated flying conditions closer to the front.

Attempts to improve field training near the front began to gain momentum in the middle of 1916, as retired RAF Wing Commander and author C. G. Jefford indicates in his book, Observers and Navigators: And Other Non-Pilot Aircrew in the RFC, RNAS and RAF. It was decided by the RFC in the summer of 1916 that an Aerial Musketry Range (later referred to as a Gunnery Range) should be established at Camiers, near Étaples, in northern France. However, it took some time for the range to be established, which was finally opened in November 1916. Towed banners and fixed targets suspended from balloons were used for air-to-air training, while air-to-ground ranges were also installed.

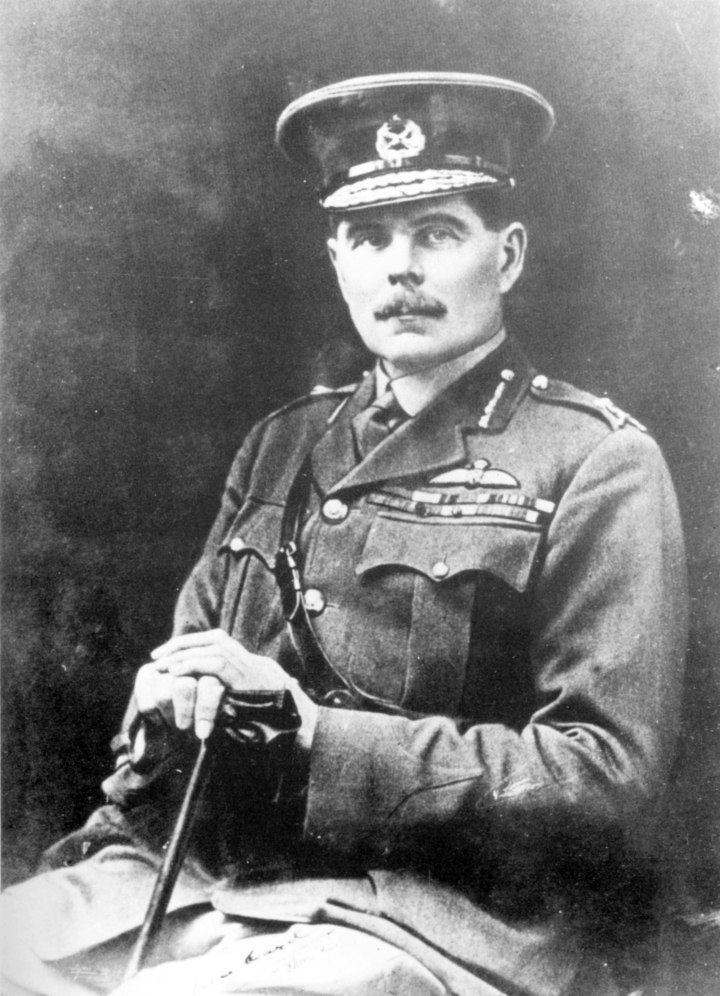

The facilities at Camiers remained in use until March 1917. While it was envisaged that they would only be used during the winter of 1916–1917, Hugh Trenchard, the then-commander of the Royal Flying Corps (and later the first Marshal of the Royal Air Force) announced in August 1917 that Camiers would be reopened during the winter of 1917–1918. Alongside Camiers’ reopening and expansion, two further gunnery training facilities were opened in France in the summer of 1918. One was established at Setques, further north; the other was established at Rang-du-Fliers.

Both the Setques and Rang-du-Fliers facilities were attached to separate Aeroplane Supply Depots — Setques serving Aeroplane Supply Depot Number 1 at Marquise, and Rang-du-Fliers serving Aeroplane Supply Depot Number 2 at Berck. Here, it was intended that the gunnery training facilities would allow replacement pilots and observers from the ‘pilots pool’ to continue practicing with machine guns while on the ground.

The picture of the Pilot Officer training, seen at the top of this story, and others taken at Rang-du-Fliers were from the camera of Second Lieutenant David McLellan. All are now housed at the Imperial War Museum (IWM) in London, and they give clues as to what the RAF was trying to achieve in its gunnery schools in France.

Improving pilots’ reactions and aiming under pressure was a big part of the equation here. Despite the relatively low speeds of aircraft during the period, firing machine guns aboard airplanes was very different from firing machine guns on the ground. This required the ability to operate aircraft guns in motion – the speed of aircraft, which would have felt especially fast to new flyers, added additional layers of difficulty for pilots and observers firing from moving positions. Combine that with hitting a quickly maneuvering target and things got very complicated. This was a three-dimensional, highly dynamic gunnery activity unlike anything before it. The image above clearly shows a silhouette ‘target’ in the distance. Designed to resemble various German aircraft of the period, notably the Fokker D.VII, targets were constructed by RAF mechanics, mounted on wooden boards, and placed at various spots around the improvised track.

Few details exist as to how the moving ‘cockpit’ was constructed, or indeed how it was powered. It’s possible that it may have relied on forward momentum (and the design on the track in relation to the sand dunes) in order to generate speed rather than being powered by an engine or motors.

The image provides a clear indication of the machine gun being used, however. The gun’s distinctive top-mounted pan magazine gives it away as a Lewis light machine gun. These guns armed practically all RFC, RNAS, and later RAF, fighters in the latter years of the war, and featured key advantages for the user. Using a gas-operated long-stroke gas piston and a rotating open bolt for its action, the Lewis gun was able to fire 500-600 .303 caliber rounds per minute, accurate up to around 2,625 feet. Rounds were fed via a pan-like magazine on the top of the gun. On the ground, Lewis guns were most commonly used with 47-round magazines, but a 97-round type was also developed for use on aircraft-mounted examples.

Significant weight was saved when using Lewis guns because airflow while airborne was significant enough to cool them, allowing for their ‘cooling jackets’ to be removed. Reduced weight and added maneuverability were combined when the guns were mounted upon ‘Scarff rings’ — a type of machine gun mounting invented by Warrant Officer (Gunner) F. W. Scarff of the Admiralty Air Department during the war for use on two-seater aircraft. This allowed the Lewis gun to be elevated and rotated around to fire on targets over a wide envelope while in flight.

The Lewis gun’s light weight, ability to fire rapidly, and maneuverability attached to Scarff rings, made them a particularly attractive choice for observers/gunners, often in support of heavier Vickers machine guns fired by pilots — a notable armaments configuration of the Bristol F2B Fighter. The combination of Lewis guns and Scarff rings was important for aircraft defense, particularly as aerial combat expanded during the war, with rear Lewis gunners providing vital cover to pilots firing in forward-facing positions.

Initially configured in a single-gun setup (notably on the Sopwith Triplane, which was introduced in late 1916) and later in twin-gun variations (including on the Sopwith Camel, which was used extensively by both the RNAS and RFC after it entered service in mid-1917), the Vickers featured a gas-boost recoil action, firing .303 caliber rounds at a slower rate of 400-500 rounds per minute. Unlike the Lewis gun, however, the Vickers was accurate at greater distances.

Pilots had a chance to train with these machine guns at Rang-du-Fliers, too. The image below shows a Pilot Officer in a raised cockpit firing the distinctive Vickers machine gun (recognizable by its indented barrel). Unlike the moving cockpit used for Lewis gun training, the cockpit here is suspended upon a wooden contraption which, presumably, allows it to be rotated side-to-side. Moreover, as part of this training setup, the targets themselves were moveable. The caption to another image taken of Vickers machine gun training at Rang-du-Fliers notes that targets would disappear after six seconds, with the system being manually operated via a set of electric controls behind the cockpit.

The gunner school at Rang-du-Fliers clearly went to great lengths to simulate the conditions of air warfare for pilots. By the summer of 1918, control of the skies over the battlefields was very much in French and British hands, while the war itself would only continue for a few more months. More than anything, the images from Rang-du-Fliers bring home just how far airpower and the emerging technologies that underpinned it transformed during the years of World War I, including how pilots and observers were increasingly trained to use machine guns.

As World War I ushered in the dawn of aerial combat and ground-based simulation to service it, more elaborate schemes to simulate aerial gunning on the ground followed. This form of training become commonplace and critical by World War II, during which the significance of air-to-air combat was paramount.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com