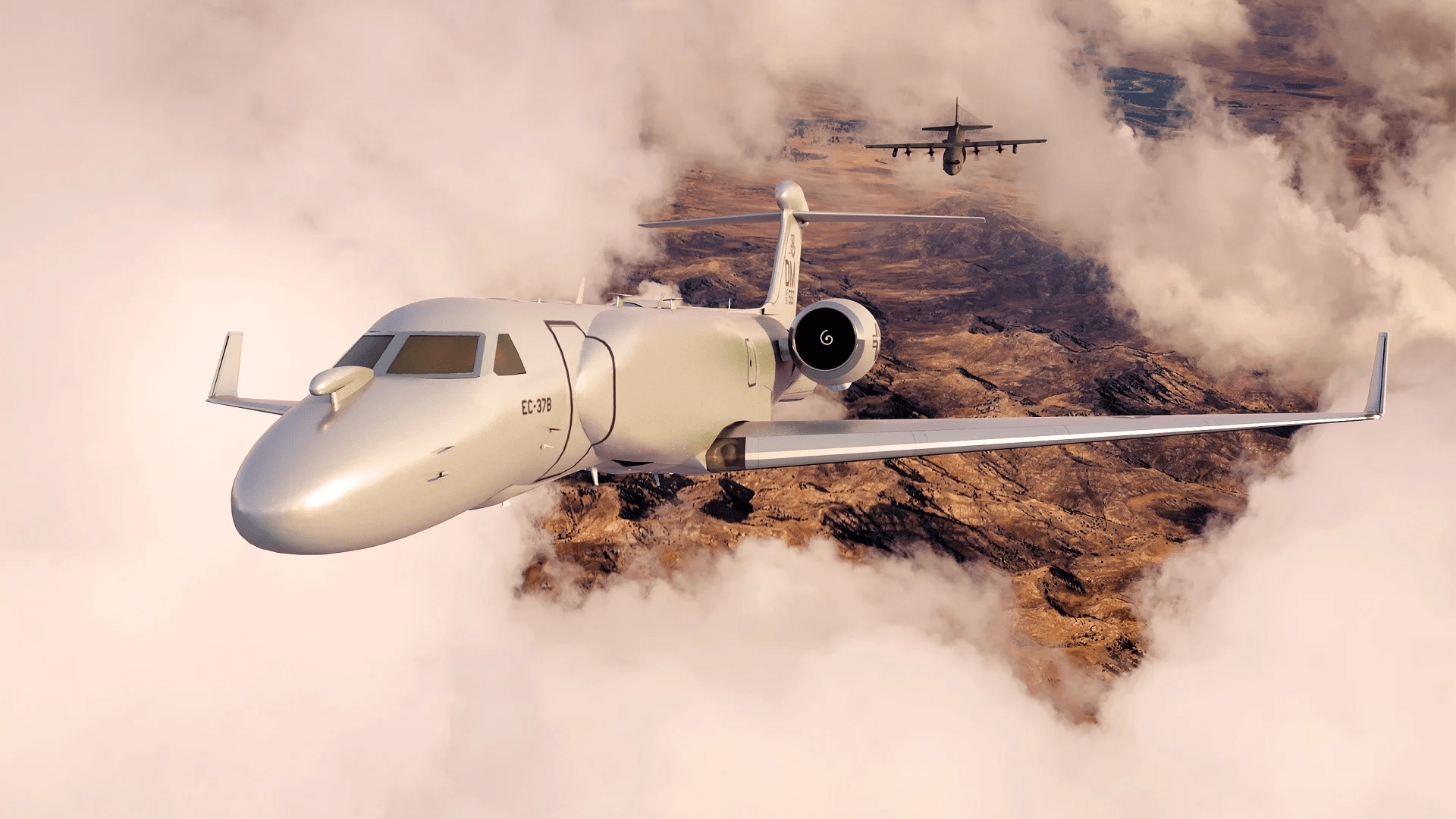

A U.S. Air Force officer with ties to the EC-37B Compass Call program has shed light on the issues affecting the system’s progression to The War Zone and made it clear just how exciting the type’s capabilities are set to be. According to the officer, the proposed Department of Defense budget for Fiscal Year 2023 presents significant implications in regard to the program’s fate now that certain cuts have threatened the EC-37’s force strength.

The EC-37B is the Air Force’s answer to its aging EC-130H Compass Call fleet, and you can read all about the replacement in this past War Zone piece. Both aircraft were designed to serve the overall Compass Call mission, which is described by the Air Force as “disrupting enemy command and control communications, radar, and navigation systems to restrict battlespace coordination.” With some airframes dating back to the Vietnam War, the Air Force’s 14 legacy EC-130H aircraft will now see many of their already proven electronic warfare technologies ‘cross-decked’ into their business jet-based successors under a conversion program conducted by L3Harris.

Under the program, L3Harris will remove as much of the EC-130H’s Compass Call equipment as possible, upgrade it, and then reinstall it on the EC-37B’s new highly modified Gulfstream G550 business jet airframes. BAE Systems will also be involved in this aspect of the contract between L3Harris and the Air Force by overseeing the systems integration portion of the cross-deck effort.

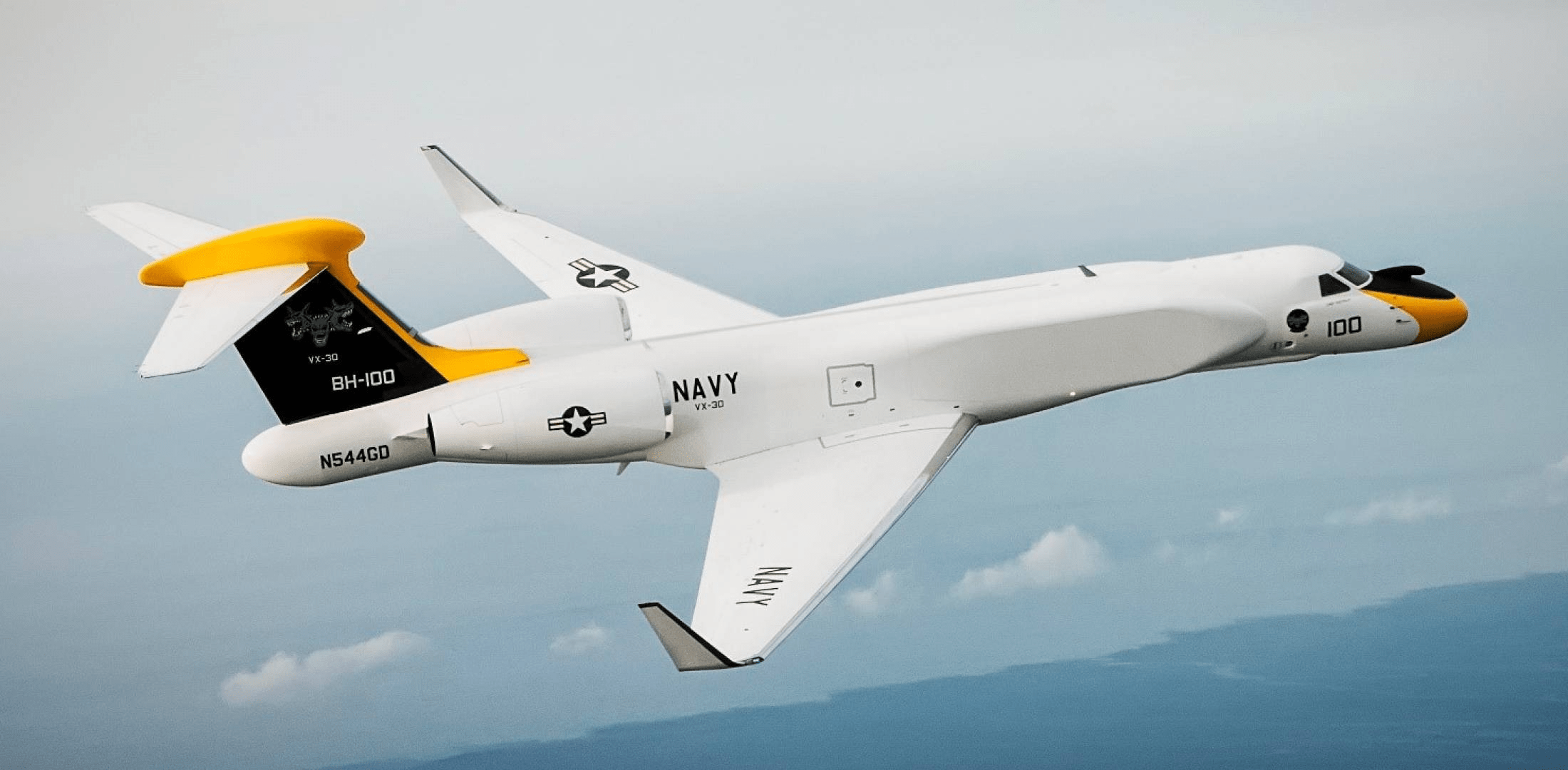

Both the EC-37B, as well as the U.S. Navy’s NC-37B missile tracking jet, use the Israeli Eitam Conformal Airborne Early Warning (CAEW) aircraft’s modified G550 airframe configuration. The type’s ability to reach higher altitudes allows it to provide effects across the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) over longer distances and larger areas, and the business jet’s overall design offers increased speed and endurance, as well.

The boost in capability that the CAEW/G550 airframe is expected to provide for the Compass Call mission will also be supported by the various electronics that will round out the new EC-37B jet. While the conversion process is primarily about cross-decking between airframes, the EC-37Bs will receive an improved overall suite of systems in addition to the benefits that the underlying aircraft offers over the EC-130H. Equipment designed to provide critical stand-off electronic warfare jamming support, other kinds of electronic attacks, and a secondary intelligence gathering functionality will likely continue to cement Compass Call in its role as a reliable, multi-use, stand-off electronic warfare capability. That is if the program receives the right attention and funding.

Throughout the year, The War Zone used publicly available Defense Department budget documents to assess the military’s goals as they pertain to the EC-37B Compass Call. In June, the U.S. House of Representatives moved to add $37 billion to the proposed defense budget for Fiscal Year 2023, and $883.7 million is meant to procure four more EC-37B jets. On the surface, it appeared that the Air Force was ready to prioritize its Compass Call fleet as the spending increase would boost the service’s original plan of buying only 10 EC-37Bs to 14, a one-for-one replacement of the existing EC-130Hs.

However, speaking to The War Zone on the condition of anonymity, the Air Force officer divulged that this isn’t the whole story.

The reality is that the Air Force underestimated the cost of implementing what is known as the EC-37B’s system-wide open reconfigurable dynamic architecture (SWORD-A) capability, which is intended to facilitate rapid upgrades for the jet. Because of this and other higher-priority modernization efforts, the service realigned funding from procurement to research and development by cutting the initial purchase of four additional EC-37Bs in Fiscal Year 2022.

Therefore, according to the Air Force officer we spoke with, the proposed additional buy of four EC-37B aircraft seen in the Fiscal Year 2023 budget request documents is instead aimed at getting the service back to its original purchase of 10 electronic warfare jets, not 14. Despite 10 jets having been the target number for a while now, the officer insisted that such a fleet would still not be enough to fight in future high-end conflicts and offered their argument as to why Compass Call shouldn’t be underfunded, as well as some unique insights into the type’s next-generation capabilities that underpin its value proposition.

Here is that exchange:

Emma: Can you flesh out the complications the Defense Department is grappling with in ordering new EC-37s?

Air Force Officer: In the Fiscal Year 2022 execution, we basically presented a budget-neutral plan, meaning we stayed within the numbers that we were given to develop our program. We pushed aircraft purchases into the future so that we could have that money for an aircraft purchase to work on modernization of the aircraft, specifically SWORD-A, which I will touch on later, because that capability is necessary based on emerging threats and how the electromagnetic battlefield has developed the way it has.

Due to a corporate decision, the Air Force did not show the budget request data beyond Fiscal Year 2022. So, what they saw is that we were asking for six aircraft and the modernization money for SWORD-A. Because they made a decision to not look forward, which they typically do, they did not see us ask for aircraft in the following years, so they took it as six.

Because that happened, the aircraft ultimately ended up on an unfunded priority list. We asked for $75 million for spare engines, and we got support from the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) and the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC), and others, but it didn’t get funded. Now we’re kind of doing the same thing again this year where we have HASC and SASC support for the four aircraft purchase, which would bring us to a total of 10, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to get funded.

The Air Force basically gets a budget and they get a big number and they have to spread that across all of their programs. And there’s a lot of things that we’re trying to do right now to modernize, so they just had to make cuts. They made a lot of cuts, and we happened to be one of them. In the fiscal year 2023 budget, they cut the purchases completely, so all remaining purchases beyond the six currently on contract are cut to “pay higher priority bills” is how it’s worded.

Whenever they make a cut, Congress is able to poke at it. That’s what happened with Rep. Don Bacon (R-NE) from Nebraska when he publicly stated that the Air Force has promised to pay for four more aircraft. So, we have some winning comms because we have a representative in the House, so that’s been helpful, and because of all this, the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) has required that we do a study on EC-37 survivability, capacity, and effectiveness. So, that’s being worked on right now to give the OSD the reasoning as to why we need these aircraft.

Emma: Tell me more about SWORD-A as it pertains to EC-37 and electronic warfare platforms as a whole. How will this affect how the EC-37 operates and fights in the EMS?

Air Force Officer: We developed the term SWORD-A to communicate with Congress because they needed something specific that they would remember, but we refer to that as our Baseline Four capability, which is already funded and on the roadmap to being developed. We’ve actually just finished our critical design review for it. SWORD-A is a complete hardware change in the aircraft and will transition to a completely open mission system to allow for maximum flexibility.

SABER, which I’ll also get into later, was basically a very small form factor software-defined radio that developed a road map for SWORD-A, or Baseline Four. These both align with the 350th Spectrum Warfare Wing‘s vision of dominating the EMS. That’s the whole point of the wing. They enable rapid reprogramming and rapid fielding of new capabilities.

They also ensure that the platform does not become vendor locked and is specifically developed to support full-spectrum operations. We anticipate that it’s going to influence other standards development, as well. When you look at Microsoft or Apple, they say, ‘Here is my software, if you would like to develop an app or a program for our software, here are our standards on the lines of code that you must write.’

Right now our platform is leading the way in having an open standard. The F-35 and the F-22 — their software does not talk to each other. They were developed to be secured and only in their platform, whereas we are saying ‘I want to have commonality and the ability to leverage any capability that the Joint Force has. And to put on my platform, because I do have the ability to stand off a significant distance from the threat, and I have a ton of power.’

And that’s SABER and SWORD-A in a nutshell. SABER was basically the crawling stage of getting to SWORD-A, and Baseline Four delivery is set for 2027.

Emma: Will EC-37s be survivable against a peer state A2/AD threat like China?

Air Force Officer: I always enjoy this question because even the study from OSD is kind of nonsense because we can look at a lot of aircraft — we have our C-135, we have our E-7, we have AWACS — and yet EC-37 flies higher, faster, and further away than all of them. So the question of survivability is interesting. For the EC-130, there’s no question: No, it’s not survivable. It can’t get as close as it needs to be to do its mission, but the EC-37 changes that because it flies 40,000 feet, can fly Mach 0.7, and flies a long way away.

Most of those questions are inspired by Chinese missile development, too. They have some long-range things, and that is why that question is always posed, to ask what effects it’s going to bring and if it will even survive once it gets airborne.

The obvious answer is yes.

Based on the EC-37’s range, altitude, and airspeed it is a much more survivable platform than the current iteration. And that was the entire intent of transitioning the platform from a -130 variant to a G550 variant.

Emma: What does the EC-37 bring to the table that the EC-130 did not?

Air Force Officer: In 2016 when we articulated the need for the new aircraft, it was because of the survivability argument. So the intent was to transition the current capability into a new platform. That being said, this is a new baseline. This is Baseline Three, the current EC-130 is Baseline Two. So it does come with increased efficiencies and operator actions, and it does come with some modernization and increased targets.

Most of that is through a capability mentioned earlier called SABER. SABER is a software-defined radio that is kind of like an iPhone and we would have an app store. So what this ‘iPhone on a plane’ will do is hook into our transmitters and basically, the programs would run on it, and we’d be able to counter emerging threats quicker because all you have to do is update the App Store, push a software update to the app to get the increased capability so that App Store and the techniques to counter radars, comms, things like that are being worked quickly through the 350th Spectrum Warfare Wing in Eglin.

We have an EMS-dominant strategy. If we lose the spectrum, we lose the ability to communicate, to work together, and so we would lose no matter how good our missiles or airplanes are. So SABER allows us to get away from vendor lock. And that’s commonly what we refer to as a bad thing, where you are owned by Lockheed or Boeing, or in our case by BAE Systems, and they basically control everything. And it’s for business practices and making money, but it also kills your ability to field things fast.

And think about your cell phone or your computers like, my goodness, they increase in capability so fast, and so does military technology now because it’s all interwoven. So you have to be able to keep up. And that’s the whole point of SABER on EC-37. SABER is being tested on the EC-130, but again, the issue with using SABER on EC-130 is the plane can’t fly high enough or fast enough. So to put it in a fight where it’s currently designed to be, it would just get shot down. It’s basically like a showstopper. It can’t fly in the airspace, so it doesn’t matter what capability it has on it.

Putting that capability on the -37 allows us to bring the effects from a lot further away. The altitude gives you an increased radar horizon. We’re looking at 250 nautical miles away to provide effects to something like communication or radar on the ground and looking at 400 miles to provide effects in the air-to-air type of delivery, so if you’re looking to target a fighter aircraft. And that’s based on a power increase and the ability of the airframe just to fly higher.

Emma: What parts of the compass call system from the EC-130 fit into the G550’s significantly disparate airframe?

Air Force Officer: That has been a struggle, specifically weight and balance, but they’ve had to do some obsolescence with the switch from one aircraft to the other, meaning we’ve had to get rid of old technology and go with new technology because it’s smaller and weighs less. So there has been a lot of modification to what hardware’s being brought over. Baseline Three was originally supposed to be put on an EC-130, but because of the smaller aircraft, we’ve had to find ways to put it on a G550-based aircraft.

That’s all going just fine, ironically, because there’s money behind it. So while we’re having issues with funding the four additional aircraft, we have the money to get the six aircraft full-up, and we have money to continue to iterate those six aircraft. But yes, there have been weight considerations and hardware changes to support a smaller aircraft dynamic and a smaller crew. We’ve used some automation because of the smaller crew, and the overall space and size.

But that doesn’t change the fact that I don’t know of a more powerful airborne jammer in the world than the one we have. If you look on the -130 there are big pods out the wingtips, and that’s an active electronically scanned array (AESA), and that has been put into the cheeks of the G550 variant. Those big bulges on the side, that’s basically a big transmit antenna, and then all the amplifiers to get all the power stacked inside right behind it at each side.

We were also able to get that power into lower frequency ranges by moving it into the EC-37, which is helpful because if we’re flying high, we can fly higher and further away and still have the same capability, which gives you more survivability. That used to be called our SPEAR pod on the -130, and now it’s just an AESA. That’s what is keeping us alive, just because it’s got so much power.

Emma: What does the Israeli CAEW G550 configuration bring to the fight for Compass Call?

Air Force Officer: Right so with the AESA radars that took the place of the SPEAR pods on the EC-130 and were moved into the EC-37’s cheek, we’ve had to expand its range more effectively in lower frequency ranges, which ultimately gave us more power in those frequency ranges, too. So, that pod is able to steer the beams off of the antenna a lot more efficiently because there’s no wingtip in the way. If you look at the SPEAR pod, there’s still about 10 to 15 feet of wing beyond the pod, so it kind of blocks its ability to jam up into very high altitudes.

Since we don’t have this issue with the cheek-mounted AESA, this allows us to look into multi-domain effects for targeting things at really high altitudes.

Emma: How much in common will the EC-37 be with the Navy’s NC-37?

Air Force Officer: We basically share platforms, and that’s about it. So avionics, engines, flight controls, airframe. But as far as inside, like the mission equipment and the arrays, all that, it’s all being purpose-built specifically for us by BAE, and it doesn’t have anything in common with what the NC-37 does.

Emma: Are there any other unique elements of this new platform that you would like to highlight? Is it aerial refueling capable?

Air Force Officer: It is not capable of being refueled in flight. And some people look at that as a problem, but the G550, even the G650, and these corporate jets in general, they’re all about seeing how far they can get these rich people all across the world without having to stop. So they fly really fast, really high, and have an impressive flight duration. Right now we’re looking at around 10.8 hours of flight duration and with weight savings, we’re continuing to look at around 11 hours of flight time.

That is a really long time to be flying. Any longer than that and you start to get into crew duty limitations. Different aircraft have different parameters for that, but the EC-37’s is 16 hours max, and that includes what time you show up for work, and we typically show up three hours prior to take-off. You add 11 and three and you’re at about 14 hours, so aerial refueling would only give us about two more hours on station to provide effects.

So it’s not aerially refuelable, but there’s also a problem with having enough fuel available to conduct war. The fighters eat up a lot of gas, and everyone has a fuel bill, and a lot of complications with conducting wars is making sure they get enough gas. That’s why part of our pitch for the EC-37 is saying that we won’t require fuel, we’ll just support with aircraft.

Emma: What do the bulges above the nose and on the rear of the tail do?

Air Force Officer: The bulge on the nose is empty, there is no current development for that. I wish I knew what the Israelis used it for. I think they might have a laser rangefinder in there, or some sort of infrared technology would make some sense, but that’s a complete guess.

As far as the tail goes, that is also empty at the moment, but we’re exploring the viability of placing an advanced ultra-low frequency array in that space. We’ve already sent the dimensions out to industry, and they’ve responded with some pretty good products. It’s a very small space to go low frequency because the lower frequency you go, the bigger antenna you need.

Emma: Will it have cognitive EW capabilities? How about the ability to network and work cooperatively with other EW platforms such as the EA-18G?

Air Force Officer: The phrase ‘cognitive EW’ is thrown around a little bit too much for how undefined it actually is. We are trying to stay away from that a little bit just because we don’t want to tie our capability to that, even though we’ve demonstrated numerous cognitive EW capabilities.

While there’s no formal definition, the program has been experimenting with artificial intelligence and machine learning to automate some interactions with the EMS and better complement lower crew size. So we definitely have some applications that do cognitive electronic warfare, but it’s a spectrum. A lot of people will use AI and machine learning and say it’s cognitive, but that’s not it. However, using open architecture through SABER and SWORD-A offers developers an easy path to test cognitive capabilities.

As for networking, we have a lot of external communications links to allow us to integrate and collaborate with the larger force package, specifically the Growlers. That being said, with stuff like SABER and SWORD-A, I have the ability to take most of the Growler’s capabilities, like their lines of code that are used to jam radars, and I can take all of those lines of code and I can do it farther away because I have more power. So, we already have a lot of their target information.

And this is good because the government already paid for target X and target Y, and they paid for it through their prime, and so if I went to BAE to pay for target X and target Y too, it’s basically like the government’s paid the same money to two different people for the same thing.

So, SWORD-A and SABER will basically allow us to share among the Air Force. I could take an F-35 waveform, an F-22 waveform, a B-21 waveform, or a Growler waveform and I can put it on my plane, and we can all work together to figure out who needs to do what because we all have similarities.

Emma: Give us your final argument. Knowing all of this, why should the OSD approve the purchase of four more EC-37s?

Air Force Officer: The EC-37 should be a 90% mission-capable rate. We’ve seen the issues that the Air Force has had with other aircraft availability and mission-capable rates, even with the F-22 and the F-35. It’s very hard to keep our fancy airplanes flying because they’re like Ferraris. They perform at a high level and then require significant maintenance. So, that’s a big change. A 90% rate is huge. It means when you want to fly, it’ll be ready to fly, which is not how it is with other aircraft.

We are also working to make sure that our electronic warfare capabilities are accurately depicted and ingested. And the virtual test and training center, which is the Nellis Air Force Base virtual environment that they’re currently working on, exists for the same reason I’m talking to you, to make sure that the combat Air Force understands what electronic warfare buys you.

And ultimately what we buy is time, and often that’s all we need. EC-37 will help make it so we can wage war on our own timeline and not let the enemy determine how and when we’re going to fight.

Contact the author: Emma@thewarzone.com