“Makes you feel like they are just keeping things from you.”

That’s how Colin Scoggins describes the U.S. military’s response to a potential unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) sighting during his time with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) at Boston Air Route Traffic Control Center. Scoggins is now retired, but his recountings of various instances when he and his colleagues saw mysterious blips on their radars or heard reports of other sightings are timelessly intriguing.

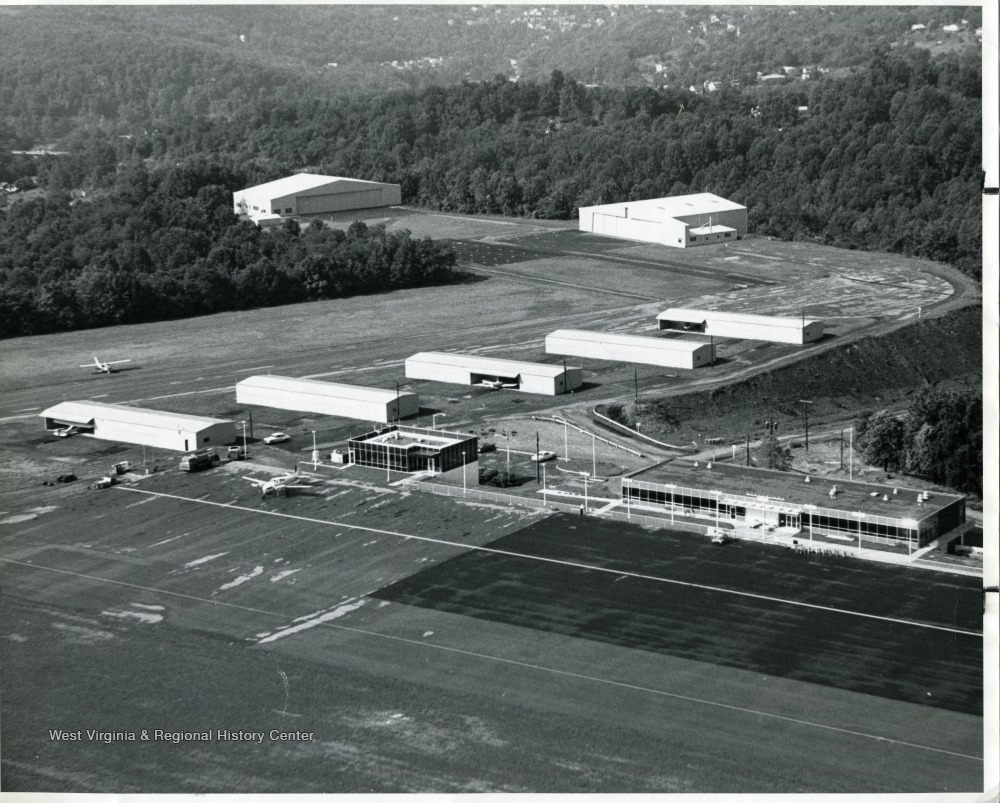

Scoggins began his career with the U.S. Air Force, working on fighter jets like the F-4 Phantom as a crew chief. Once he got out, he started school at West Virginia University and slung drinks part-time at a local bar to pay the bills. It was at this establishment that he happened to meet three air traffic controllers (ATC) who were working the tower at Morgantown Municipal Airport in the spring of 1981.

“They were joking about going on strike in June, and I was almost thinking about going back into service,” Scoggins told The War Zone. “And they said, ‘No, you should become a controller.’ So, I actually took the test back then, and then they ended up going on strike in August and I had already moved back up to the northeast and I called over to the regional and told them that I was interested in, you know, becoming a controller.”

Unfortunately, he was told that the test he had already taken was out of date and that he’d need to take the new one. Upon passing the updated exam, Scoggins found out it could be about a year until he learned whether or not he had gotten the gig. Young, in a relationship, recently accepted into Northeastern University, and in need of reliable income, Scoggins once again considered going back into the Air Force. That was until just a couple of days after Christmas when a request for an interview turned up in the mail. In 1982, Scoggins started training for his position with the FAA.

Once officially hired, he worked the airspace in northern Maine until a powerlifting accident resulted in a shoulder injury that required Scoggins to take medication for an extended period of time. Because of that, he was taken off the floor and moved to the aerospace office where he would work throughout his healing process. After working in this role and serving a bit more time on the floor, Boston Center’s military liaison was removed from his position in 1995, and Scoggins was asked to work both the military and civilian airspace sides of his department in the interim. Then in about 2005, he was relieved from his controller position and became Boston Center’s military specialist until he retired in 2016.

With over three decades of experience working for both the military and the FAA, Scoggins isn’t short on stories. Retellings ranging from some of the first RQ-4 landings to his hand in the tragic United 93 flight are just a couple of the career-defining moments that Scoggins could share, but his experience with strange things that occurred in or near the nation’s airspace is nonetheless notable. While some were either quickly or gradually debunked, the happenings still act as unique insight into how the FAA and the military handled UAP sightings, especially prior to 9/11.

In terms of UAP protocol, Scoggins explained that his department had a relatively standard requirement to report anything they had seen or received accounts of to the team’s supervisor who would then pass it along to the operational manager. He said it was also procedure to report it to the military, and for Scoggins, that meant contacting the Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS).

“Understand most controllers are a certain personality,” Scoggins said. “Normally we are controlling individuals. We like to control pretty much everything and none of us have any patience. I still don’t have any patience today after being retired for six years.”

Sometimes, though, Scoggins said that a particularly busy day would only warrant an acknowledgment of a possible incident before time constraints would require that the team moved on. Others would lead to dedicated investigations.

“As far as how most controllers feel if they are real, I think most think they are,” Scoggins said. “And whether they believe they are not from our world, I am sure there are a few. I would think most believe they are probably from our world and probably our own government.”

He added that there was a small percentage of conspiracy theorists among the ATCs, just as there are in the general public, who will believe what they want to believe. Although, he doesn’t recall ever being told not to report his findings, nor did he think that any controller felt as though their job was in jeopardy if they did.

“I had three instances I can think of,” Scoggins said. “One of them was definitely a meteor smashing into the ocean. One pilot saw it and thought it was a UFO. Another guy that was flying at a 90-degree angle from him saw it and said, ‘No, it’s definitely a meteor that went right to the ocean.’ So we could write that one off.”

Meteors are often mistaken by onlookers as UAPs or UFOs. The chunks of cosmic rock both big and small hurtle through space all the time, sometimes entering the Earth’s atmosphere and emanating a fiery glow as they burn up. This can also cause the meteor to break apart, eventually becoming multiple pieces so tiny in size that it essentially vanishes into thin air. These characteristics could lead many to believe they had just seen a UFO despite it being a common celestial occurrence.

“Another one was at dusk or dawn,” Scoggins said. “We had a Boeing 747 pilot swear that one of the passengers seated in the back said that they saw rockets fired at their plane. Back then we used to have air traffic assistants for tracking systems and they were usually ex-pilots. This guy was an ex-Boeing 747 right seater and he says, ‘You know what my guess is? Was it in a turn?’ And I told him, yeah, and he goes, ‘At dusk or dawn the light can shoot out the window across the wing, and then when they straighten the wing back up the light comes back at you.’”

Because such an optical illusion could convince someone with an untrained eye that a rocket was being fired at their plane, Scoggins was the first to admit that the air traffic assistant’s guess was totally viable. But he made sure to take into consideration the specific airspace that the 747 was flying in at the time.

“That pilot was near warning area 102, which was sometimes used for live fire, but normally it was not,” Scoggins added. “We also didn’t have any military activity going on in warning area 102 at the time, so it couldn’t have been a rocket fired at them because we had nobody up there.”

According to GlobalSecurity, warning area 102 is a part of the Boston Area Complex in the waters adjacent to the coasts of Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and New York. The overall military operating area also includes warning areas 103 and 104, Small Point Mining Range, and submarine transit lanes. In terms of military activity that is carried out in this area, beyond aerial training, those operations could include surface-to-air gunnery, anti-submarine warfare tactics, and both surface and subsurface exercises.

Scoggins used this knowledge to help him determine whether a rocket or missile had actually been fired not only at the aforementioned 747 but at the tragic Trans World Airlines flight 800 (TWA 800) that crashed during the middle stretch of his career, as well. Before the reasoning behind the TWA 800’s explosion was ultimately reached, there were claims that a missile had been fired at the airliner.

“Now it wasn’t but a couple of years later when TWA 800 went down, and I spent two years working on that,” Scoggins said. “I had to look for any military activity that was going on at the time and possibly could have shot a rocket, and we had a C-130 out there at the time in warning area 105, but they wouldn’t have been firing any rockets.”

After a four-year National Transportation Safety Board investigation, Scoggins’ work paired with the help of all other experts and departments that were involved later determined that TWA 800’s disastrous mid-air explosion was caused by flammable fuel vapors in the center fuel tank likely from a short circuit. The incident killed all 230 people on board. But that wasn’t the last of Scoggins’ encounters with strange events in the airspace around and off of America’s east coast.

“The only other one we did have was a high-moving aircraft at 49,000 feet on a straight line passing over New York City doing about 900 knots,” Scoggins said. “We brought it up to the military three or four times and they just kept saying, ‘Nope, we don’t see anything.’ And I think it was definitely a [real radar] target. So my guess is that the military knew who it was, and they weren’t going to tell us.”

Scoggins is confident in this assertion because, before 9/11, he said that the military shared the same radars that Boston Center used on the coast. He explained that if he was using the radar located in Riverhead out of Long Island, so was the military. If he was using Bucks Harbor radar up in Maine, the military was looking at the exact same thing.

He even added that the military actually owned those sites and often adjusted them and did work on them. For some perspective, he went on to mention that his department also had a site out in Skowhegan, Maine which was called an Air Traffic Control Radar Beacon System and those were non-military and didn’t look for raw radar returns. However, Bucks Harbor and Riverhead did have the raw, primary radar that the military actually used, so Scoggins was sure that the Pentagon was looking at the exact same information but insisted that they hadn’t seen anything.

“The military has a lot of stuff,” Scoggins said. “I’m not really a believer of actual UFOs, but I’m a firm believer that if the SR-71 was made in the 1960s, I’m sure we have a lot better crap out there now. Who knows what we really have, but I know there are other controllers out there that have seen a lot more.”

Thank you to Colin Scoggins for taking the time to recount his experiences with the FAA for this piece.

Contact the author: Emma@thewarzone.com