It’s difficult to overstate the significance of the V-2 rocket. Named the A-4 (Aggregat 4) by German Army Ordnance, the rocket was dubbed “Vergeltungswaffe Zwei” (“Vengeance Weapon Two”) by the Nazi propaganda ministry in 1944. The world’s first liquid-propellant rocket vehicle to be built in large numbers and the first ballistic missile, the V-2’s shadow extends well into the 20th century — with its design inspiring many modern-day rockets and launch vehicles. Even Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its use of short-range ballistic missiles early on, as well as other standoff weapons today – from repurposed surface-to-air missiles to Iranian drones – can draw a line to the use of Germany’s ‘Vengeance Weapons.’

Now, historian Dr. Charlie Hall traces the history of the V-2 from its Nazi origins to its impact on intercontinental ballistic missile development later in the 20th century. In the first of three special articles, he explores the development of the V-2 in World War II and its early post-war afterlife.

Part One: The Dawn of the Missile Age

On September 8, 1944, the face of warfare was forever changed by two explosions. The first took place in Maisons-Alfort, a suburb to the south-east of Paris, at around 11:00 AM, claiming six lives and causing injury to 36 others. The second occurred on Staveley Road in Chiswick, a leafy and well-heeled part of west London, at approximately 6:45 PM. The explosion rocked the surrounding houses, even though there were no bomber aircraft overhead and the air raid siren had not sounded. It caused thousands of pounds worth of damage and claimed three lives – 63-year-old Ada Harrison, three-year-old Rosemary Clarke, and Sapper Bernard Browning, on leave from the Royal Engineers. These nine unfortunate souls, in Paris and London, were the first ever victims of a ballistic missile attack.

The weapon which had killed them was the V-2 rocket, launched by Nazi artillery units stationed in Belgium and the Netherlands – the one which hit Chiswick had been fired from a location some 200 miles away. Traveling faster than the speed of sound, the V-2 arrived without warning; the rushing noise it made as it hurtled to earth could only be heard after it had hit its target. Its payload was a one-ton high explosive warhead, which shattered windows, knocked down walls, and left an enormous crater in the middle of the street.

The speed and surprise of its arrival, and the destruction that it delivered, made the V-2 the herald of a new era of warfare. Every long-range ballistic missile used since 1944 has been built on the foundations laid by the V-2. Not just that, but the technology which allowed the Nazis to kill people in Paris and London in September 1944, also took the first men to the moon, less than 25 years later, in July 1969.

Despite its dark roots, the V-2 is an icon of twentieth-century warfare and of technological accomplishment. Surviving examples stand today in the atria of both the Imperial War Museum in London and the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, exemplifying its ability to straddle two worlds. In this article, I will sketch out how the V-2 was developed, the story of its deployment during World War II, and how its true potential was not fully realized until after 1945.

The arrival of the V-2 in September 1944 may have come as a shock to the people of Paris and London, but its development had been underway for many years, and the foundations on which it was based can be traced back to the 1920s.

After World War I, Europe and the U.S. underwent a major surge in public interest in science and technology. Its potential for violent destruction had been seen on the battlefields of Belgium and northern France, but now there was a desire to see how it could be wielded for more peaceful ends.

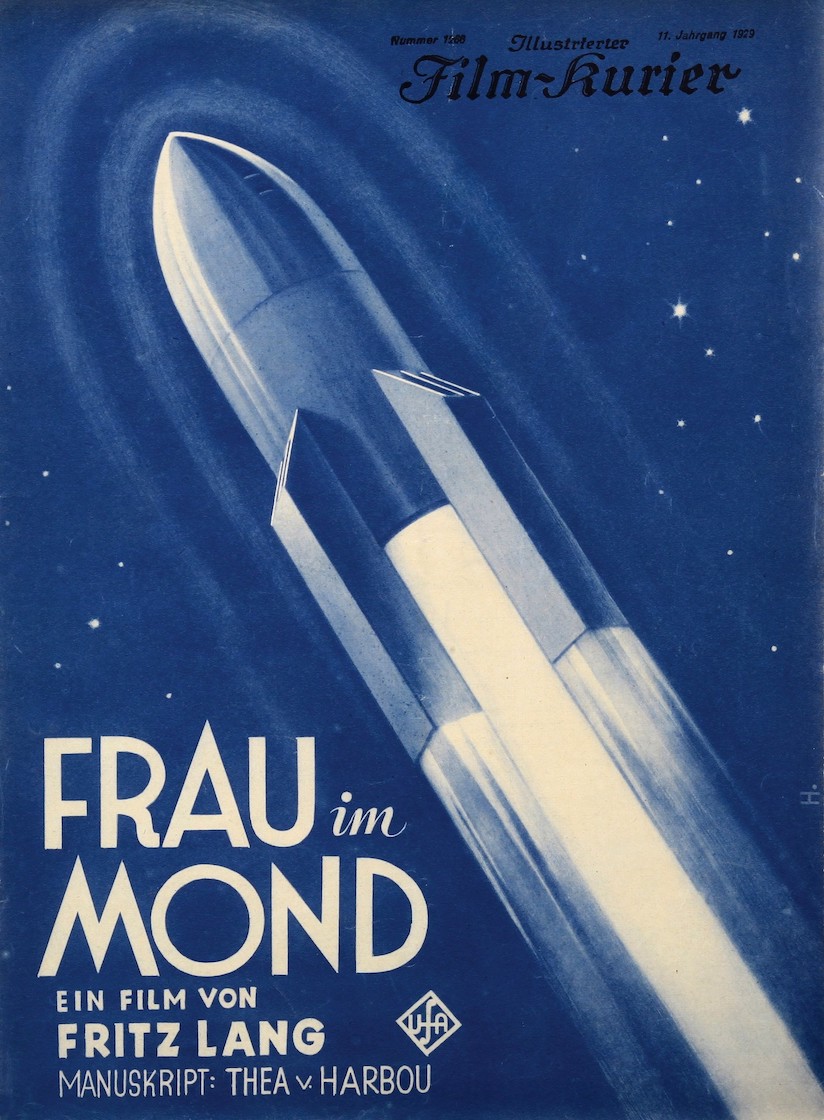

Rocketry was just one area of newly enthusiastic scientific endeavor. Far-sighted engineers, like Robert Goddard in the U.S. and Hermann Oberth in Germany, not only conducted pioneering experiments but actively sought to whip up public support for this new technology. Oberth even served as technical advisor on Frau im Mond, a path-breaking and remarkably realistic science fiction film directed by Fritz Lang, about a rocket-powered journey to the moon.

Young people across the world were inspired by these experiments, and their fictional representations, leading many to pursue careers in engineering. Chief among these individuals, at least as far as the story of the V-2 goes, was Wernher von Braun. Born in 1912 in Prussia to a wealthy family – his father was a politician and civil servant, his mother a member of the minor nobility – he developed a passion for astronomy, and an aptitude for physics and mathematics, while still a child.

When he turned 18, he began his studies in mechanical engineering at the Technical University of Berlin, and also joined fellow enthusiastic amateurs in the Spaceflight Society. In 1934, he completed his doctorate in physics at Friedrich-Wilhelm University and began his career just as Adolf Hitler was consolidating power. Hitler’s ambitions for a major war of domination in Europe meant that there was demand, and thus funding, for a military rocketry program. Von Braun – ever the pragmatist – set aside his dreams of space travel and followed the money, beginning work on a long-range ballistic missile for the Nazis.

By the time war broke out in 1939, von Braun was technical director of a massive army research center at Peenemünde, on Germany’s Baltic coast, where he was responsible for developing the A-4 – a missile that would later be known as the V-2. In July 1943, von Braun and his associates traveled to Hitler’s secret Wolf’s Lair headquarters and screened a short film of a V-2 launch. The Fuhrer was so impressed that he reportedly said, “if we had had these rockets in 1939, we should never have had this war.” Orders were given to commence mass production.

One month later, plans were thrown into disarray when the Royal Air Force conducted a major bombing raid on Peenemünde, as they suspected it was being used to produce rockets. The raid was only a limited success, but it did force the Nazi regime to move the rocket manufacturing facilities to an underground factory, known as the Mittelwerk, built into the Harz Mountains at Nordhausen, where this top-priority project would be safe from any further Allied bombs.

Here, in horrendous conditions, slave laborers from the nearby Dora concentration camp were worked to death on the production of V-2 rockets. Laboring and living far underground, they were deprived of fresh air and natural light, as well as food and rest, and were subject to the arbitrary violence of their SS guards. Indeed, more people died building the V-2 than were ever killed by it in action.

By the time the first V-2 rocket hit Paris and London, World War II had less than a year left to run, and the tide had firmly turned against Germany. The Red Army’s hard-won victory at Stalingrad in early 1943 had been followed by the steady rollback of Nazi forces in the East, while June 1944 had seen troops from the U.S., Britain, Canada and their allies land in Normandy and begin their assault from the West. Hitler knew he needed a dramatic transformation in fortunes if he had any hope of staving off a terrible defeat.

As such, he ordered the beginning of the vengeance weapon campaign. Vengeance Weapon 1 (or V-1) was a flying bomb (an early cruise missile) that had been developed by the Luftwaffe in parallel with the V-2. The first of these were launched against Britain on June 13, 1944, only a week after D-Day. They proved a nasty shock to those in the firing line but a series of counter-measures – anti-aircraft fire, barrage balloons, and attack by fighter aircraft – meant that their impact could quickly be reduced.

Then, in September, as we have seen, Vengeance Weapon 2, or the V-2, arrived. There were no adequate countermeasures against this faster-moving missile and Allied commanders knew the only solution was to overrun the launch sites in France and the Low Countries.

Londoners faced with this new threat throughout the autumn and winter of 1944-45 responded in various ways. Some reacted with abject terror: “It’s awful isn’t it? You never know whether you’re going to be here from one moment to the next.” Others were more fatalistic: “What I say is if your name’s on it you’ll get it. No good worrying ‘cos you can’t do anything about it.”

Both of these responses would no doubt have pleased Hitler, who knew the best hope of the V-2s – too few in number and too inaccurate to seriously cripple infrastructure or industry – was to deal a powerful blow to the morale of war-weary civilians. He would perhaps have been less thrilled with the comments of one 90-year-old woman who, when asked what she thought of the rockets, replied “The rockets, dearie? I can’t say I’ve ever noticed them.”

Certainly, the V-2 did not live up to Nazi hopes of it being a war-winning weapon. It had almost no effect on the course of a conflict which was already being decided by the sheer volume of resources – weapons, raw materials, finances, manpower – available to the Allies. But it is perhaps unfair to judge the V-2 against such unrealistic criteria.

London was hit by 1,115 V-2 rockets over a seven-month period, each of which delivered a one-ton explosive warhead. This resulted in the destruction of 20,000 houses and the loss of 2,855 lives. For comparison, over just two days in February 1945, Allied bombers dropped 3,900 tons of explosives and incendiaries on Dresden, resulting in approximately 24,000 fatalities and the obliteration of a 1,600-acre area in the city center.

The Nazi regime could not produce the V-2 in great enough numbers, or ensure they hit their target with sufficient frequency, to make a serious dent in the Allied war effort. Moreover, the resources needed to sustain the V-2 program were so substantial that they left other, perhaps more valuable, parts of the German war machine, such as fighter aircraft, neglected. The physicist Freeman Dyson, who worked for the RAF during the war, commented that the Nazis’ focus on the V-2 “was almost as good as if Hitler had adopted a policy of unilateral disarmament.”

Some have surmised that the V-2 ultimately arrived too late to turn the tide of the war back in Germany’s favor. However, it is perhaps more accurate to suggest that the V-2 arrived too soon – before the advent of guidance technology sophisticated enough to guarantee real accuracy – to fully realize its true potential.

It was that potential, however, that ensured the V-2 had a lifespan beyond World War II. As soon as the Nazis signed the unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945 – and in some cases beforehand – Allied officials began combing through the laboratories, factories, and research facilities of the ruined Reich, looking to extract anything of worth developed, produced, or invented by Germany during the war.

The V-2 was practically at the top of that list. It offered visions of a new type of warfare that could be fought at great distance without needing to put one’s own soldiers or aircrews into harm’s way. With the advent of the atomic age after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, it seemed like the ideal delivery system for these new and supremely powerful warheads. One American journalist, writing just two weeks after the atomic bombs were dropped, described the coupling of atomic energy with rocket propulsion as a “Frankenstein’s monster,” resulting in “the most terrible weapon ever known”.

This was heightened even further by the onset of the Cold War. All the victorious Allies now began preparing for a new conflict; one that might well need to be fought between continents and where the ability to strike at distance could prove to be the difference between victory and defeat. The V-2 seemed to provide the shortcut to future ballistic missile superiority.

The Allies took different approaches to unlocking the secrets of the V-2. The British conducted Operation Backfire, in which three captured V-2s were launched from the German North Sea town of Cuxhaven, under experimental conditions. One of the launches was even attended by foreign dignitaries and members of the Press.

The U.S. and the Soviet Union planned on a more long-term basis. As well as evacuating tons of materiel – complete rockets, various components, blueprints, laboratory equipment, machine tools – they also sought to secure the services of the scientists and engineers who had worked on the V-2 program.

Both sides offered lucrative deals and attractive conditions, and neither were above applying a bit of pressure as well. The Soviets even kidnapped some specialists who were less keen to head east of their own volition. In this race for the human spoils of war, the U.S. seized the biggest prize – Wernher von Braun and his team – but both were able to provide their own nascent rocketry programs with a major infusion of German expertise and experience.

In the Soviet Union, efforts to unlock the secrets of the V-2 yielded the world’s first inter-continental ballistic missile – the R-7 – in May 1957, and a vehicle capable of launching the first artificial satellite – Sputnik I – was put into space in October of that same year. In the U.S., the V-2 provided the foundation of both their ballistic missile program and their space program. Wernher von Braun’s wartime accomplishments were eclipsed by his design of the Saturn V rocket which took men to the moon in 1969.

The story of the V-2, then, is a complicated one. Developed by those who dreamed of space travel, it was used to rain destruction on London, Paris and Antwerp, among other places, and cost the lives of thousands who were forced to build it in the most appalling conditions. It failed to deliver on Hitler’s promise of a ‘wonder weapon’ which would change the course of the war but, in the years after 1945, it proved to have a more transformative effect on conflict, and on human endeavor more widely, than anyone could have predicted – which will be explored more deeply in the next article.

Dr. Charlie Hall is Lecturer in Modern European History at the University of Kent, UK. Charlie’s research centers on ideology, propaganda, and society in twentieth-century Europe and Britain. His first book, British Exploitation of German Science and Technology, 1943-1949 (Routledge, 2019), explores how Britain made use of Nazi equipment and expertise after World War II.

Contact the editor: oliver@thewarzone.com