For their time, pirates were among the most fearsome threats that any sailor could encounter on the high seas. They were known for their brutality, cruelty, and the fear they instilled in all their victims. While The War Zone has previously explored the unique cultural cachet and mythmaking that has accompanied the history of piracy ever since its heyday, it now turns its attention to pirates’ use of weaponry — often the key to their success.

It is the early 18th century, the height of the Golden Age of Piracy. Pirates roam throughout the Caribbean and up and down the coast of North America seeking loot and riches. They have become known as terrors of the seas due to their harsh battle tactics. Once they arrive in popular shipping lanes — perhaps near the Carolinas or a plantation island like Jamaica — they select their victim: a merchant ship full of valuable goods such as textiles, sugar, and rum. The pirates pursue the ship until it cannot escape their grasp.

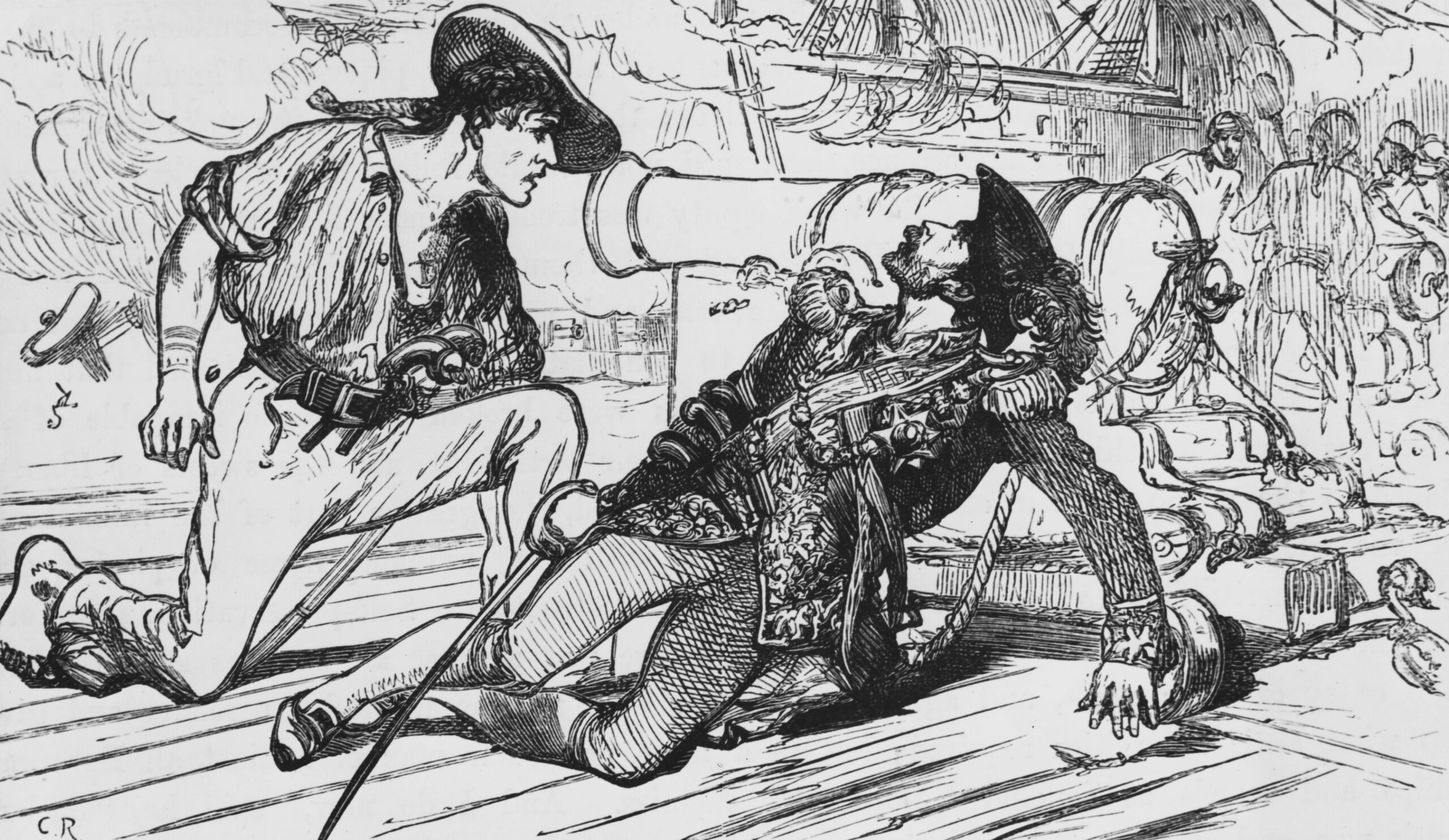

Every crewmember aboard a pirate ship is tense with anticipation. They all have their roles. The gunners are below deck readying the cannons with various types of shot. Cabin boys are prepared to grab more gunpowder, weapons, or anything else that might be needed in battle. Those aboard deck face their foe, cutlasses shoved through their belts and pistols strapped around their midsection for easy access. They wait for their captain’s orders before unleashing their fury.

As well as the ship itself, items such as muskets, pistols, cutlasses, cannons, and even flags were vital to pirates’ success and survival. They needed to keep all their equipment in top shape and therefore pirates were much more diligent, careful, and organized than most other sailors of their time — a reality about pirates that might be difficult to imagine. But without careful weapon care and usage, the pirate endeavor would undoubtedly fail.

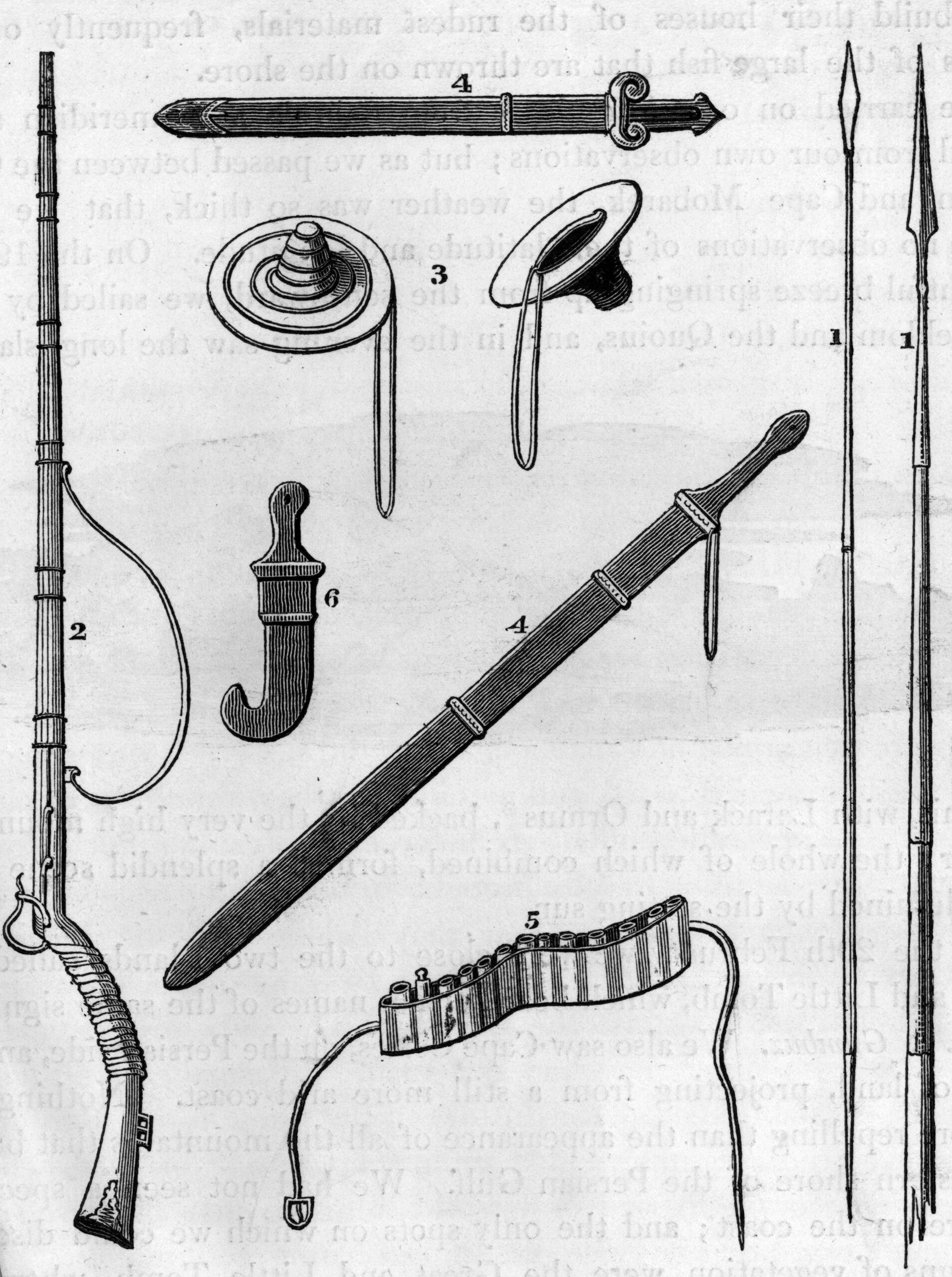

The first thing pirates had to do to maintain safety on their ships was to protect their gunpowder. The tiniest bit of spilled powder could be the cause of a massive explosion during battle, so it had to be closely monitored at all times. This was no easy feat at sea because gunpowder cannot get wet, or it becomes useless. Even if wet powder managed to dry, it would never work the same again. One of the ways to alleviate this risk was by spreading out the powder among various pirates. They wore cartouche boxes on their belts or shoulder straps, which contained tightly wrapped cartridges of powder.

With gunpowder properly stored away, pirates had to make sure to care for their muskets. The musket was so important to them that Alexander Exquemelin, author of The History of the Buccaneers of America, first published in 1678, claimed that “[pirates] name the musket their arm” as if it was actually part of their body. This weapon was a long-barreled, large-bored, and club-butted flintlock that had roots in pirates’ days of buccaneering. If they sailed a ship that did not have any cannons, which was extremely rare but possible, muskets became their most important lifeline because they often gave pirates the upper hand in battles (if they managed to fire them accurately). Their firing range to ensure true fatal effectiveness was 250 yards, although they could fire up to 500 yards. Muskets required dexterity and skill to work properly and avoid unnecessary death to the operator.

The pirate operated their musket by half-cocking the hammer and safety position while taking the cartridge out of their cartouche box. Using their teeth, they would rip the cartridge open, pour in a small amount of powder, and close the frizzen (the L-shaped piece of steel hinged at the front of the weapon). The rest of the powder was poured down the barrel followed by a small metal ball that was pushed down with a narrow ramrod at least three times to secure it. Once the pirate was certain that their musket was fully and accurately loaded, they would lower it to waist height, draw the hammer back to full-cock, raise the musket to their shoulder, aim, and fire.

All of this had to be done during the heat of battle and often took an expert shooter up to 20 seconds — an eternity in such a life-or-death situation. Mistakes easily happened. The pirate’s mouth might water and get the powder wet, preventing its firing. If their hands shook, they might drop the cartridge altogether or they might bungle the ramrod and miss the mouth of the pistol. Ideally, a pirate needed to have at least two loaded muskets on their person when they entered the battle.

Despite the pirates’ devotion to their muskets, the most commonly used weapons were pistols and cutlasses. Pistols were close-range weapons, meant to only be fired at no more than three yards. The barrels were a foot long, making them excellent clubs after discharging a bullet. Some pirates carried several pistols on their body. According to Captain Charles Johnson, author of the 1724 book A General History of Pyrates, the pirate Edward Teach (commonly known as Blackbeard) wore “a sling over his shoulder, with three braces of pistols, hanging in holsters, like bandoliers.”

If a pirate chose not to use a firing weapon, they likely grabbed their cutlass. Cutlasses, unlike swords, had short, sturdy blades with a strong protective hilt often made of iron or brass. The shorter blades allowed for small, fast thrusts rather than engaging in intricate swordfights. Their small size was ideal for a pirate to keep one on themselves during times of extreme physical duress in compact spaces. Like the pistol, they were meant for close combat.

Cutlasses and pistols were so important they became an emblem on some pirates’ flags, such as Jack Rackham who designed the iconic version of the Jolly Roger with a skull and crossed cutlasses during his pirate career in the 1710s and 1720. Several years later in 1726, the American Weekly Mercury reported that a group of pirates off the coast of Curacao flew “with their Black Silk Flag before them, with a representation of a Man in full Proportion, with a Cutlass in one Hand and a Pistol in the other Extended…”

There is little known about pirates’ fighting techniques with their cutlasses. We can only get an idea from modern practices, which are nothing like the crowded heat of battle on a rocking ship. As stated above, this weapon was specifically made for basic cuts, thrusts, and parries like broadsword or fencing techniques rather than swords, which were much longer and required more distance between opponents. The goal was to hit the opponent without receiving an injury by controlling the victim’s blade or using deliberate thrusting, which left that person vulnerable.

Cutlasses had a blade usually only between 28 and 34 inches, which is why pirates were partial to them. Broadswords, on the other hand, were much longer and took up too much room on the body. According to Benerson Little, the author of The Sea Rover’s Practice, training for combat with broadswords was a difficult endeavor because pirate ships were already too crowded with items such as “cannons, bitts [upright posts on the ship’s deck for fastening mooring lines and cables], masts, rigging, coamings, hatches, and scuttles, not to mention the many implements and accessories of war strewn about.” There just was not enough room to practice proper sword-fighting techniques with larger weapons.

Ships were armed with cannons, known as guns, of various sizes for battle, which defined the pirates’ vessels. By the 18th century, English guns were named by their weight, and they ranged anywhere from four to as large as 16 pounds. Other European ships could have guns up to 24 pounds. These weapons were usually made of iron or bronze, but the latter was rare because it was extremely expensive.

Round shot was the most common form of cannonball and was used against hulls and masts at further distances. If a ship was at close range, the cannons were fitted with two round shots, which were large cannon balls used to damage hulls and rigging on ships. Grapeshots were also used, which were small canvas bags packed with multiple small iron or lead balls that exploded on impact, sending wood shards and shrapnel everywhere. These were used when pirates intended to face their foes in armed combat or if they wanted to damage their victims’ defenses enough so they could get aboard. Case shot was similar to grapeshot except they were small packets of iron shards and other various pieces of scrap metal that also exploded on impact. However, unlike grapeshot, case shot was intended specifically to maim or kill the pirates’ victims.

Cannons were mounted on bed carriages with wheels to allow for movement and to reduce recoil. Eighteenth-century cannons had some limitations in that they were only managed with two tackles, which were hooked from the carriage to the eyebolts. While cannons were extremely effective in damaging other ships, they also posed a great risk to their own crew because gunners were always right in the line of enemy fire.

Swivel guns were a type of cannon used on smaller ships and were muzzle-loaded, like muskets. These were smaller and intended to specifically target people on the enemy ship.

Once the pirates had their weapons assembled, they were ready for battle.

Each person had a specific role to guarantee success. Hammocks were stowed into the hold or mounted against the walls of the ship to provide extra protection against cannon hits and flying splinters. Canvas and other types of cloth were run along the rails around the ship’s perimeter to give the pirates some concealment to lead a better surprise attack if necessary.

The gunners had the most important role: overseeing the readying and loading of the cannons. Two or three men, on average, worked on each gun while an officer stood ready to command anywhere between five and 10 guns at a time.

Amid all this harried preparation, the gunners had to make sure the powder stayed dry so the cannons could fire shot. Like musket preparations, gunners prepared gunpowder, shot, cartridges, rammers, and handspikes to load each cannon.

Not only that, but they also had to cast protections against fires from their own guns or any that might hit their ship. One solution was to spill water onto the deck hoping it would stay wet enough to prevent anything from catching fire. In the meantime, the carpenter made sure to check the pumps and prepared shot plugs and lead sheets to deal with any holes. The surgeon waited in the cockpit of the ship, ready to treat the wounded as they would undoubtedly start pouring in minutes after the commencement of battle.

Finally, the captain would ready the crew with a hearty speech, and everyone would take a dram of liquor to fortify their courage. Once battle began, a ship could be completely decimated. If the pirates’ firepower was powerful enough, they could literally smash their foes’ vessels into pieces.

Some of the pirates’ most important weapons might be less obvious, one being fear tactics in battle. The purpose was to get their victims to surrender as fast as possible to avoid a long-drawn-out bloody battle.

Displaying the pirate flag was the most effective way to avoid intense conflict because it immediately informed their victims of the terror the pirates were about to unleash upon them.

Finally, the most important weapon above all else was the ship itself. The design of a pirate’s ship could be the difference between survival and failure. Pirate ships were extremely varied, and pirates often had to improvise to make them as efficient as possible. Ships had to be exceptionally seaworthy since pirates sailed around the Atlantic for extended amounts of time fighting and braving extreme storms. The ideal ship had to be fast enough to attack and sail off quickly enough that its victims would not catch up with it. Not only did a ship have to be fast, but it also had to be large enough to accommodate numerous guns to be as threatening as possible. The size and prowess of a ship encouraged pirates’ foes to surrender quickly and move up the maritime hierarchy.

Large, heavily armed ships gave pirates a certain prestige and amount of pride. However, size could be a problem. They could not always find a port that could support them. A large ship also limited the number of safe shores to hide and repair the ship, often by turning it on its side and caulking the bottom. If pirates sailed in large ships, they had to remain in active posture, constantly deployed. The only way they could hide in smaller inlets or rivers was if they switched out their large ships for shallow-draft vessels like sloops.

No matter what, though, any ship of any size required maintenance and care. In many ways, a small ship, of between 30 and 60 tons, was ideal because it was suited for navigating areas crowded with craggy coasts and narrow inlets while being faster than any larger ships that might pursue it. Smaller vessels were also easier to maintain and would represent less of a financial risk.

Without carefully maintained items such as muskets, pistols, cutlasses, flags, and ships, pirates would not have been able to be successful in their battles. Very often, the difference between life and death was their discipline in taking care of their materiel. These weapons were so important that they were even part of the pirates’ identities. They brandished their deadly instruments and intimidated their victims into surrender. If that did not work, then they were more than prepared to fight to the death with their pride in their hands.

Rebecca Simon’s latest book, The Pirates’ Code: Laws and Life Aboard Ship is out now from Reaktion Books.

Contact the editor: thomas@thedrive.com