Defense contractor Anduril’s announcement last week that it had acquired aviation firm Blue Force Technologies and its Fury drone design was a major development for both firms. Beyond the acquisition being massive ‘next steps’ in the evolution of Fury and for Anduril’s rapidly evolving portfolio, it serves as a glimpse of some of the foundational changes that are on the horizon for the historically rigid air combat aircraft industry and its primary benefactor, the Pentagon.

The War Zone has been following the development of Fury very closely since it was publicly announced and this piece is based on multiple interviews with Blue Force Technologies and Anduril over the past two and a half years.

It details how a small underdog aerospace company set out to disrupt the air combat space by taking a big swing and how that swing just got much, much bigger.

This is the story of Fury.

The Acquisition

Pitched in the past primarily as a pilotless ‘red air’ aggressor jet, Fury’s design could take on a slew of other roles and missions — which Anduril is betting on. This comes at a time when the U.S. military is actively pushing for huge new fleets of highly autonomous uncrewed combat aircraft. The U.S. Air Force’s drone requirements, in particular, have changed massively in the last few years, and Fury finds itself well-positioned to be highly relevant to that service’s needs.

Anduril revealed its acquisition of Blue Force Technologies on September 7. As a result of this, the latter company has ceased to exist as an independent brand and it, including its approximately 90 employees and two separate facilities in the Raleigh, North Carolina area, is now operating as a division of Anduril.

“What Blue Force has done is the same thing that Anduril has always done since we’ve been a company, which is build up conviction about capabilities and technologies that need to exist and then move out to develop and build and field them wherever possible,” Chris Brose, Anduril’s chief strategy officer, told The War Zone in an interview last Friday. “That’s what Blue Force did with Fury. That’s what Anduril has done across the board with a lot of capabilities.”

“So, I think in this respect, the acquisition of Blue Force for Anduril is another step in that process,” Brose, who is also the author of The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare, added. “So, it’s a recognition that this is where our own journey has been moving.”

California-headquartered Anduril has an increasingly diverse portfolio, but has focused heavily on artificial intelligence software and smaller drones since its founding in 2017. It is not in the business of building larger, high-performance unmanned aircraft — yet.

Fury was a central factor in the discussions that led to Anduril’s acquisition of Blue Force Technologies, but the latter company’s work extended well beyond that drone. It specialized in advanced concept design and engineering, rapid prototyping services, including in the digital space using advanced modeling tools, and carbon fiber composite manufacturing.

The acquisition of Blue Force Technologies “started with some initial conversations – we were all in this ecosystem, Anduril providing mission autonomy and other capabilities… we were an air vehicle provider trying to find a collaborator in order to provide that solution,” Andrew Van Timmeren, director of Air Dominance Systems for Anduril, told The War Zone in a separate interview last week. “It’s just two companies looking to make a difference in the same space and… it was just kind of natural for us to come together.”

Van Timmeren was previously vice president of Blue Force Technologies and is a retired U.S. Air Force fighter pilot who flew F-22 Raptors. He still often goes by his callsign “Scar.”

“It’s a real complementarity between not just the visions that I think motivated Blue Force Technologies to design, develop, and build Fury, and the vision that Anduril has had in pursuit that we’ve been down in terms of software and other kinds of autonomous systems, but also now the ability to bring those things together and really start to get after these more complex warfighting problems that increasingly the Department of Defense is demanding,” according to Anduril’s Brose.

But to really understand how all this came to be and its potential impact in the air combat space, we must look back to the genesis of Fury and how Blue Force’s vision was truly ahead of its time.

The origins of Fury

The development of Fury traces its origins back to the late 2010s as an advanced drone concept of Blue Force Technologies, initially dubbed Grackle, according to Anduril’s Van Timmeren. The company was able to present the idea of Grackle to the Air Force, including to Gen. James “Mike” Holmes. Holmes was deputy chief of Staff for Strategic Plans and Requirements from August 2014 until March 2017 and then became head of Air Combat Command, where he served until his retirement in 2020. Air Combat Command oversees the bulk of the Air Force’s tactical combat aircraft, as well as most of its crewed and uncrewed intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) fleets.

“We’re just a small business, but we got this pretty novel idea: nap-in-the-earth fighter[-like drone]” intended to primarily perform intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions, Van Timmeren told The War Zone. “And they said, ‘sorry guys, we don’t have… a formal requirement for [that] … but keep at it kid, keep going.'”

“Somebody in that briefing actually pulled them off… to the side of the meeting, or after the meeting in the hallway, and said, ‘Have you looked at high-performance aircraft for adversary air purposes?'” he continued.

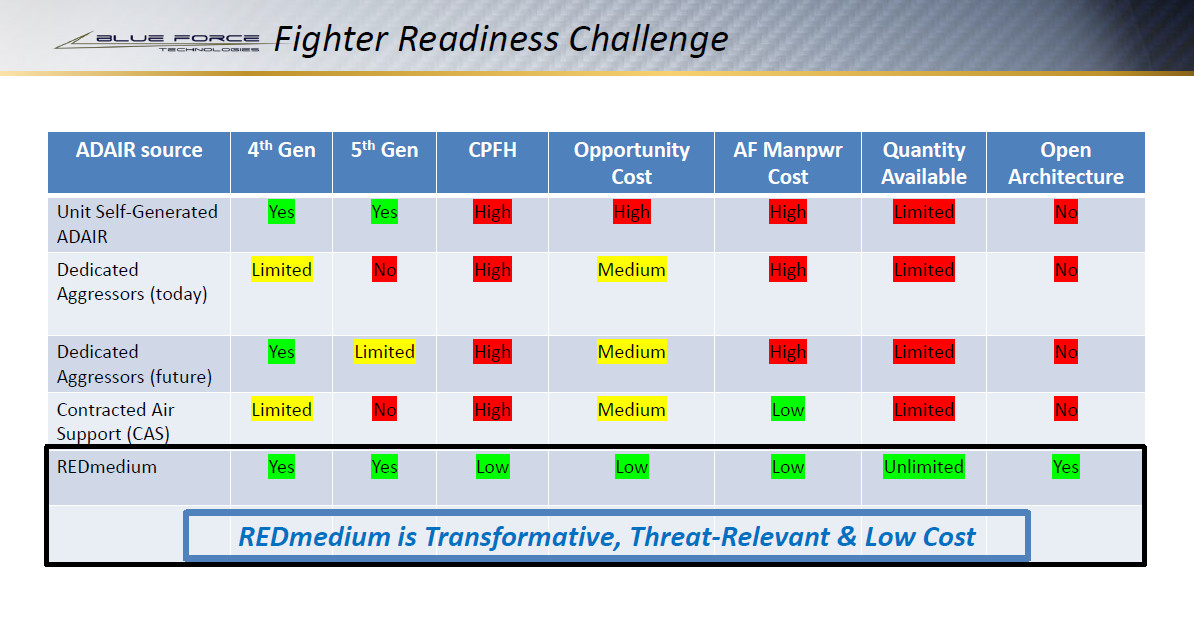

Adversary air (ADAIR), also known as “red air” or aggressors, refers to mock aerial opponents utilized during training and test and evaluation activities. At this point in time, contractor-owned and operated aggressor services was a business area that had already been growing for years and was on the cusp of an even greater expansion in terms of U.S. military contracts. However, most companies in this space used – and still do today – vintage tactical jets, or even aging business jets, which are expensive to operate and cannot simulate current-generation threats. With such old and finicky platforms making up most of the commercial adversary air fleet, the area looked ripe for disruption, which Blue Force Technologies aimed to do.

The Grackle concept subsequently evolved into what was first dubbed REDmedium and then was renamed Fury. Between 2019 and 2020, Blue Force Technologies conducted initial work on the project using a combination of internal funding and small contracts from a U.S. Air Force organization called AFWERX. The Air Force established AFWERX in 2017 as an internal technology incubator intended to help speed up the development and acquisition of new technologies.

“We avoid referring to this [the internal funding] as IR&D [independent research and development] funding because, for large OEMs [original equipment manufacturer] with a lot of cost-reimbursable contracts, they get to charge their IR&D to the government,” Scott Bledsoe, then president of Blue Force Technologies, told The War Zone in 2021. “In our case, we are not able to take advantage of that, so our internal funding is profit from commercial activities that our owners have elected to re-invest in the program.”

“We… have applied to AFWERX’s STRATFI [strategic financing] program to take advantage of SBIR [Small Business Innovation Research] matching funds which will make the program look 1/3 less expensive to the Air Force,” Bledsoe, an aviation industry veteran who previously worked for a number of other companies, including Northrop Grumman subsidiary Scaled Composites, well known for its often unusual and forward-thinking designs, added at that time. He is now

chief engineer, air vehicles and general manager, Aerostructures at Anduril, according to his profile on LinkedIn.

Though not a large existing aerospace or defense contractor, Blue Force Technologies did have a history of working with big-name aviation firms like Boeing as well as the U.S. military, through the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). From the beginning, the manufacturing of complex carbon fiber composite structures was a major component of the company’s business. That experience factored directly into the development of Fury.

In March 2022, AFWERX selected Blue Force Technologies’ STRATFI proposal, a deal that had an initial value of $9 million and a $50 million ceiling. Later that month, the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) announced that its Aerospace Systems Directorate had awarded Blue Force Technologies a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) contract for work on Fury specifically to support a program called Bandit.

“The Bandit program aims to provide an air vehicle solution for the unmanned ADAIR capability which, when integrated with autonomy, mission payloads, and sensors, will revolutionize the adversary air training mission and provide key opportunities for pilots to interact with the unmanned systems in a training environment,” an AFRL press release at the time explained. “The air vehicle is a part of a proposed autonomy-based system providing adversary air training for Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps fighter crews at greatly reduced costs compared to current manned capabilities.”

“These small unmanned ADAIR systems can be flown in training scenarios so that fighter pilots can train against tactically relevant adversaries in threat representative numbers,” Alyson Turri, the Bandit Program manager at AFRL, said in a statement accompanying that release. “The goal is to develop an unmanned platform that looks like a fifth-generation adversary with similar vehicle capabilities.”

Fury takes shape

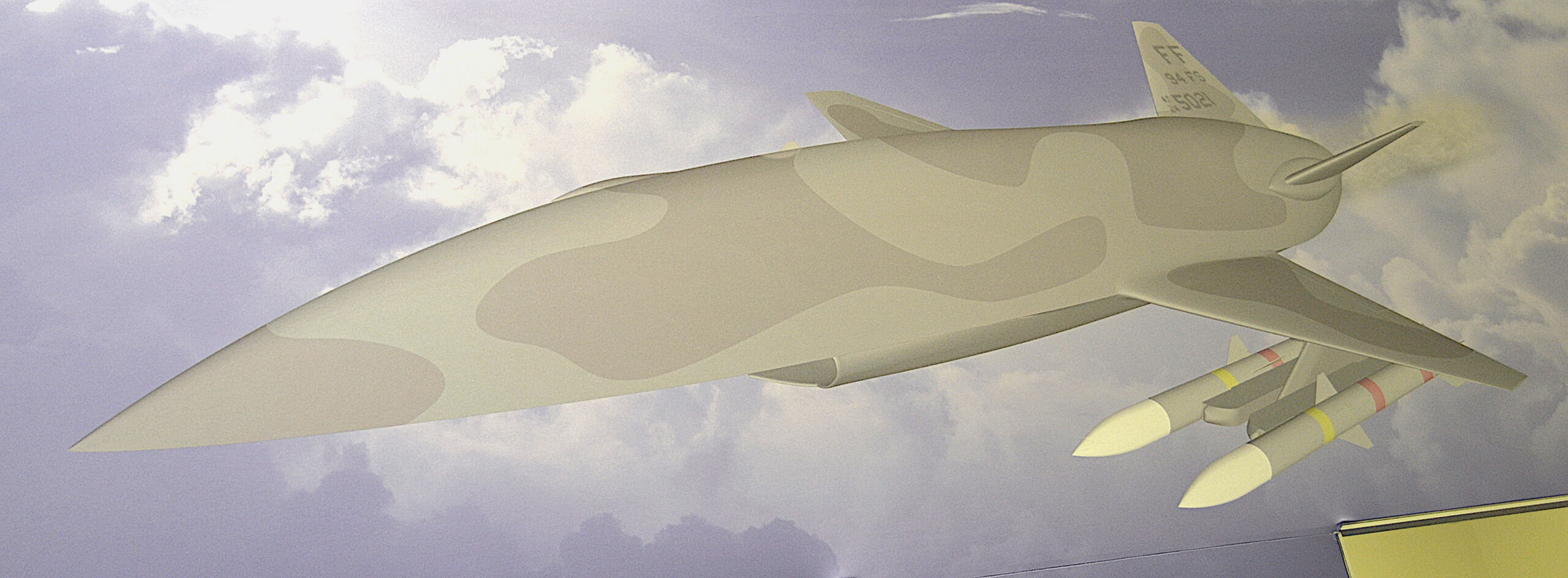

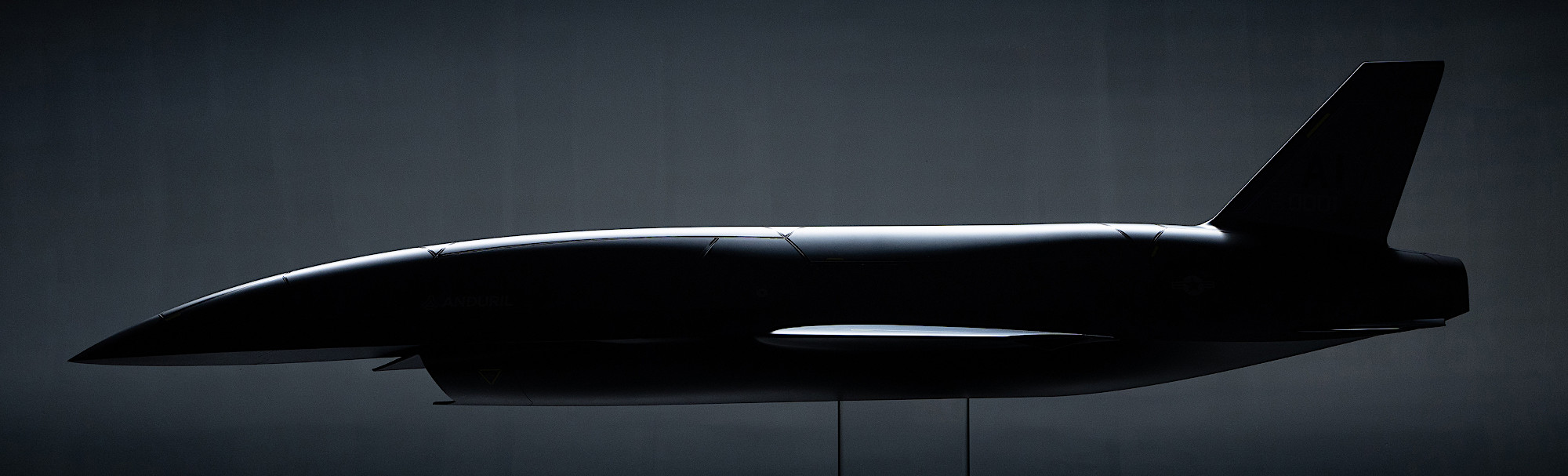

Well before 2022, Fury’s design had solidified around a broadly fighter-like planform with some stealthy attributes and tricycle landing gear intended to take off and land from established runways like a conventional aircraft. It has a single ventral air intake for the engine under the central fuselage and relatively traditional nose, wing, and tail sections. In the past, Blue Force Technologies said it expected it to be around 20 feet long and have a wingspan of some 17 feet, or about half the physical size of an F-16 Viper fighter.

At the time the AFWERX and AFRL deals were announced, there was no work being done to actually construct a Fury prototype, but Blue Force Technologies had built what it called an “iron bird” to do integration and testing work in the meantime. This test fixture, which was made out of welded steel, according to Van Timmeren, had real actuators and other systems linked to computers that allowed engineers to get valuable data on how various hardware and software components worked and interacted with each other ahead of future fabrication, as well as ground and flight tests, of a full-up prototype.

While it didn’t have a physical prototype yet, Blue Force Technologies still had very clear performance and capability targets for the Fury design, which was expected to have a maximum gross takeoff weight of around 5,000 pounds. The drone would be constructed predominantly from carbon fiber and be powered by a single 4,000-pound thrust class Williams International FJ44-4M turbofan engine. An FJ44-series engine was and remains a very logical choice given that versions of these fuel-efficient turbofans are in widespread use, including with business jets like a chunk of the popular Cessna Citation family, and there are well-established supply chains and support infrastructure globally to sustain them as a result. A version of a commercial engine in such widespread use could even allow them to potentially be put on a cost-per-hour program contract, where all engine costs are fixed.

In terms of targeted performance, Blue Force Technologies had designed Fury to be able to fly at altitudes up to 50,000 feet and at transonic speeds of up to around Mach 0.95. The goal was for the airframe to be able to perform at up to +9 Gs and down to -3 Gs for short periods, and be able to pull +4.5 Gs for more sustained portions of its flight while operating at around 20,000 feet, all depending on the drone’s exact loadout.

Anduril’s Van Timmeren told The War Zone last week that Fury’s expected size and performance specifications remain unchanged. He also disclosed a focus on good short-field performance, that is to say being able to take off from and land on shorter runways, in the drone’s design.

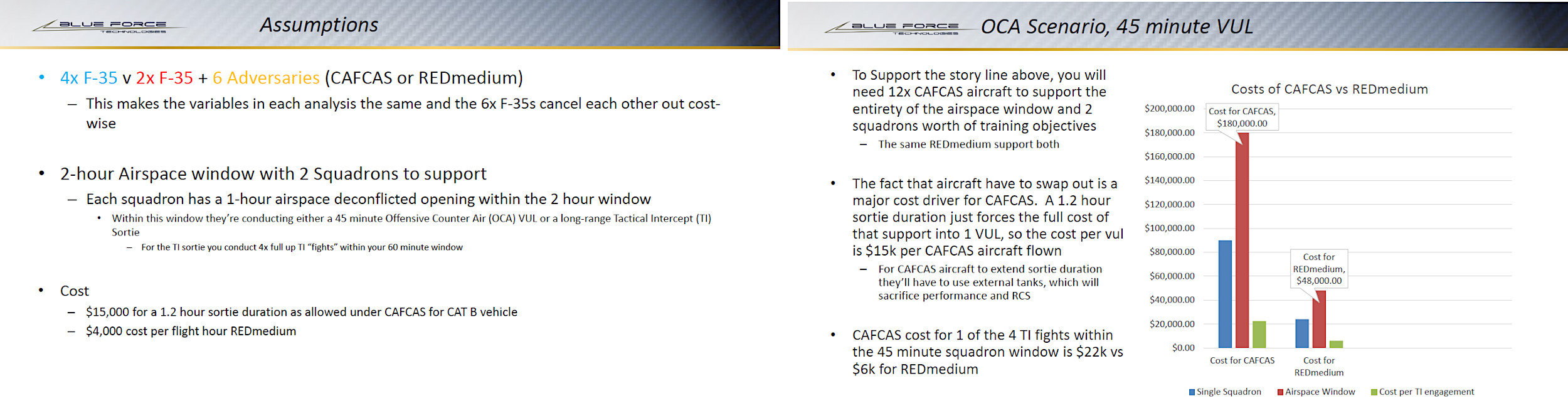

“Our market research has shown that you can do very credible ADAIR work at high subsonic speeds,” Blue Force Technologies President Bledsoe had told The War Zone in 2021. “The CAF CAS [Combat Air Force Contracted Air Support] contract is instructive here: its structure shows that RF [radiofrequency spectrum] and EA [electronic attack] capabilities are more important than top speed.”

CAF CAS is an Air Force program that dates back to the late 2010s and has provided a multi-year, multi-billion dollar contracting vehicle for hiring private contractors to provide “red air” aggressor support for training exercises and other activities.

“We want to be well positioned to take advantage of the rapid evolution in engines,” Bledsoe had added at that time. “One of our strengths as a company is an in-house propulsion flowpath design group, so we have the ability to quickly evaluate new cycles from engine companies and perform our own inlet/exhaust duct design to match engine and airframe.”

“We want to increase top speed and the primary limiting factor is that in-production engines in this thrust class currently are all designed for business jet applications,” he continued. “We have done some basic [six degrees of freedom] work to find maneuvers that would allow us to go supersonic for a short period of time as a near-term enhancement. Longer-term, we are working on augmentor technology that would allow us to break Mach 1 in level flight, as well as working with an engine OEM [original equipment manufacturer] on a next-generation engine that may be able to get us there.”

In January of this year, Blue Force Technologies announced that it, in cooperation with AFRL, had completed a successful ground test of a portion of Fury’s propulsion system.

An emphasis on modularity

From the outset, Fury was designed to be highly modular with the ability to accommodate various payloads, weighing up to 400 pounds in total, internally to give the drone additional capabilities, as required. These could include active electronically-scanned (AESA) radars, infrared search and track (IRST) sensors, and electronic warfare suites. By 2022, Blue Force Technologies had already built a representative modular nose section for the “iron bird” test fixture to support payload integration testing.

Fury is “a ‘Software-defined aircraft,’ which means that we can alter the vehicle performance, sensor usage, and jamming capabilities in flight depending upon which adversary platform we are trying to match, the loadout they would be carrying, and the tactics they would employ,” Blue Force’s Bledsoe explained back in 2021.

Overall, “we are looking for it [Fury] to look, act, and smell like a fifth-generation fighter. So, it can replicate, you know, the pacing threats, which everybody knows in the air domain,” Van Timmeren added in a previous interview with The War Zone in 2022, referring to things like China’s J-20 stealth fighter and, to a lesser extent, Russia’s Su-57 advanced combat jet. “We want it [Fury] to be the appropriate physical size, but also that… [it takes into account] radar cross-section, and we’re looking to manage that appropriately.”

“We want to make sure we integrate payloads that would facilitate an F-35 guy or a Raptor guy… looking down on their glass and having it ‘see…’ have it displayed as what they want it to be,” he added.

A modular, open-architecture approach inherently presents advantages when it comes to upgrading a system or otherwise adding in new functionality down the line. This, in turn, can have cost benefits, as well.

So far, Blue Force Technologies, and now Anduril, have declined to offer a specific unit cost target for Fury.

“We are going to be [in] what has been defined as the ‘attritable’ space, somewhere between two to $20 million dollars — we are leaning more towards the lower end of that span — as far as purchase cost of an aircraft,” Van Timmeren told The War Zone last year. “When it comes to cost per flying hour… we are going to be looking at the low single-digit thousands [of dollars] per hour.”

It is not clear at this time if these targets have changed or not.

The term attritable typically reflects aircraft designed with a balance between price and capabilities, which is intended to make it less of a problem from various perspectives if they don’t return after their sorties. Another useful framing is to view designs described this way as being cheap enough to allow for greater willingness to lose them on high-risk missions while still being capable enough to be relevant for those tasks.

In the interview last week, Van Timmeren said that the central focus cost-wise for Fury is currently on affordability, a term of art that the U.S. Air Force has been increasingly using instead of attritability. Still, as with ‘attritable,’ the specific definition of what qualifies as ‘affordable’ remains somewhat nebulous, as you can read more about in detail here.

Controlling Fury as an aggressor

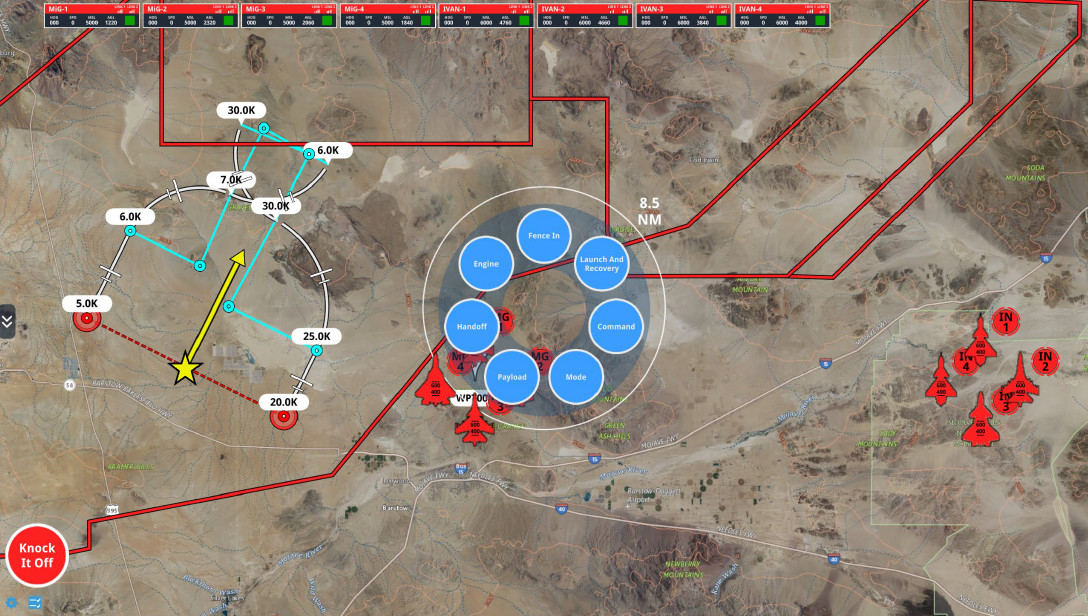

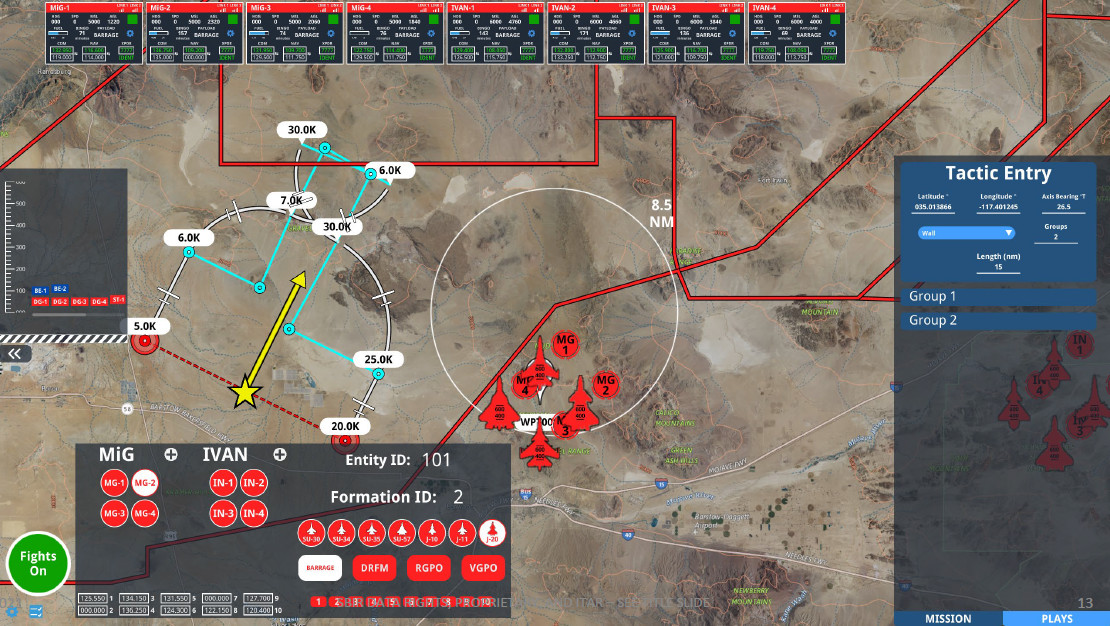

In terms of actually operating Fury, the goal was for the drones to have a semi-autonomous control arrangement for their adversary mission. The expectation has been that the drones will receive instructions via a control system on the ground, but then carry out those tasks in an automatic fashion that is monitored by humans.

“We are working with Autonodyne, which is a spinout of the avionics company Avidyne. We are developing an ADAIR-focused version of their GCS [ground control system] that is really a supervisory console more than a traditional GCS,” Blue Force Technologies’ President Bledsoe told The War Zone in 2021. “Our goal is for it to be completely intuitive for a fighter pilot to sit down and create ‘plays’ in the same way that they currently create them in Powerpoint for their kneeboard.”

Autonodyne has a long history of building customizable ground control systems for a wide variety of uncrewed aircraft, as can be seen in the video below and which you can read more about here.

“In working with the Air Force, we believe it is important that one operator be able to supervise 4-8 aircraft from a single GCS. In typical usage, the operator loads multiple plays in the aircraft, receives verification from the 6dof [six degrees of freedom] that the mission is within the capabilities of the aircraft. The operator sits on top of the outer loop, and can intervene with pre-defined actions related to sensor employment, jamming, or reactions to blue missile shots,” Bledsoe had added. “The GCS has… data for all participants, as well as perfect awareness of red aircraft routes, so it will ensure deconfliction of all aircraft during a vul.”

“Vul” is short for “vulnerability window,” a term used to describe the period in which aerial combat, either mock or real, actually occurs within the course of a sortie.

“We are leaving the mission computer architected and open, and with enough horsepower on it to facilitate the layering in of whatever autonomy solution the government would like,” Van Timmeren said in the context of the company’s current contract with the Air Force in his interview with The War Zone in 2022. He cited work being done by the Air Force as part of its Golden Horde program and by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) through its Air Combat Evolution (ACE) project as examples of potential sources of relevant technology. Golden Horde is centered on the development of autonomous networked munitions capabilities, while ACE’s primary focus has been on exploring how artificial intelligence (AI) could be utilized in crewed and uncrewed aircraft to help automate various aspects of air combat.

Even at the time, these were just some of the known projects the U.S. military was pursuing with regard to advanced autonomous capabilities and supporting developments, especially in AI and machine learning. This arena has only grown since then. Additional work on autonomy capabilities, as well as other research and development related to advanced uncrewed aircraft, has been, and still is, occurring in the classified realm.

It is also worth noting that the underlying software in drones with high degrees of autonomy can make use of data collected on each sortie to ‘learn’ how to better perform. This machine learning aspect would have been a major part of the Fury aggressor program. It is possible to mature those algorithms entirely in a digital space, too, running simulated engagements thousands or even millions of times to allow the system to better perform on actual missions.

In his most recent interview with The War Zone last week, Van Timmeren also further highlighted the benefits of machine learning when paired with unmanned systems.

“As we do anything in life [as humans], your muscles can grow strong as you do with repetition, especially with appropriate learning and instruction. And as you don’t do something, it’s a muscle that atrophies, right?” Van Timmeren said. “You go weeks out of the jet in the [F-22] Raptor and get back in and be like, ‘Okay, take this a little bit slower. Let me try and get all that squared away.’ Because even your brain is a muscle and its pathways can atrophy.

With “an unmanned system like this [Fury], when leveraging some semblance of mission autonomy, those muscles don’t… atrophy. … If you train it to do something yesterday, a month from now, that memory is still stored at that level,” he continued. “Leveraging realistic simulators, you have the opportunity to train [an uncrewed aircraft] without even using it at all.”

“And that actually encompasses the human operators, as well,” Van Timmeren noted. “As an autonomous air vehicle, you still want to have a human on-the-loop. You’re trying to remove them out of the loop. They’re not in it like in the cockpit, but they’re on it providing maybe mission command. And you can do all of that without the actual periods flying… [using] advanced mission autonomy capabilities.”

An uncrewed aggressor revolution?

For many years, Blue Force Technologies had made a detailed case for how Fury’s combination of capabilities would make it an ideal “red air” aggressor for many mission types.

Integrating more stealthy fifth-generation aggressors, or at least surrogates, crewed and uncrewed, that can come close to portraying them, into large-scale exercises and more routine training has been a growing priority for the Air Force, as well as the U.S. Navy and Marines, for years now already. There is also a need to emulate ever-more capable enemy cruise missiles, including stealthy types. Just having enough targets in the air of any kind to represent a peer threat scenario has also been a major hurdle to overcome.

Data that Blue Force Technologies previously provided to The War Zone said that the Air Force, by itself, had a requirement for around 100,000 ADAIR sorties every year, the vast majority of which involve beyond visual range (BVR) training scenarios. This total includes support for large-scale exercises and more routine training, and can involve simulating hostile fighters and other aerial threats like incoming cruise missiles.

It’s just a fact that private red air contractors, and even many U.S. military units, simply cannot fully represent high-end opponents in a training environment. Adversary air companies continue to primarily fly very dated combat jets at significant cost, and are only now beginning to transition a small portion of their fleets to fourth-generation fighters. Upgraded radars, infrared search and track systems, datalinks, and electronic warfare systems can allow older jets to act as surrogates for newer fighters, but only to a certain degree.

This was part of the reason why Air Force officials revealed last year that they were not planning to exercise an option to extend a contract with private adversary firm Draken International to provide its services at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada.

Further underscoring this reality, earlier this year, the Air Force reactivated the 65th Aggressor Squadron at Nellis, the service’s premier air combat training hub, equipped with F-35A Joint Strike Fighters. This is the Air Force’s first dedicated adversary unit with stealth fighter jets and is officially focused primarily on replicating Chinese threats during daily training and large exercises, including iterations of the world-renowned Red Flag series.

At the same time, it is equally true that it would be prohibitively costly to operate and maintain an aggressor force of sufficient size to meet the still-growing demand for advanced adversaries equipped with crewed stealth fighters like the F-35A. This is something The War Zone has highlighted on multiple occasions in the past.

This was the overall ecosystem in which Blue Force Technologies had presented Fury as a potential game changer in the past, specifically with regard to advantages in terms of costs to operate and maintain, and overall flexibility.

Blue Force Technologies’ Bledsoe told The War Zone back in 2021 that the company was targeting a flight hour cost of “under $5,000” for Fury. This number may have grown since then, but if it is anywhere near it, it has the ability to result in a major disruption for the commercial adversary air space. Flight hour costs fluctuate regularly due to a variety of factors, including basic inflation, but the cost-per-flight hour to operate an F-35A Joint Strike Fighter has been pegged at around $36,000 in recent years. The price per hour to fly the F-22 is roughly double that. If Fury can indeed be flown for anywhere near $5,000 per hour, that would make it far cheaper to operate than even older non-stealthy fighters. For example, this would be roughly around a quarter of what it costs per hour to operate an F-16C/D Viper. Even older, lower-performance, nearly antique tactical jets that make up the majority of the contracted red-air missions today cost significantly more to fly per hour.

The previously stated goals for Fury included being economical beyond just the per-hour flight cost metric. Blue Force Technologies envisioned a typical training sortie lasting just over four hours. The drone would carry an additional hour’s worth of fuel in reserve to help ensure it can get back safely in the event that it has to fly around bad weather, misses its initial landing attempt, needs to divert to an alternate airfield, or runs into other issues.

“We want to break the paradigm of ‘one vul per sortie’ … so that we spend less time doing ‘admin’ phases of flight (takeoff, cruise out, cruise home, landing),” Bledsoe explained in 2021. “If you look at typical contractor ADAIR [adversary air] today, it’s a 20-minute vul at 100nm [nautical miles] in a 1.2-hour flight, so the blue training value delivered is small, and timing becomes crucial to getting everyone set in the airspace at the right time.”

“Our vehicle… carries internal fuel for two x 40 minute vuls per sortie at 150nm radius. This means we can takeoff prior to the fighters we are training with, cruise to the far side of a typical special use airspace, do 40 minutes of training, reset and loiter [for] 30 minutes, then train another group of blue air for 40 minutes, before cruising home,” he added. “All in, we provide a lot of flexibility, as we can do three vuls at a more typical radius.”

Bledsoe further noted that the range and endurance benefits could be of significant interest to the Navy and Marines, especially during training from a carrier offshore. “We can cruise out farther if we need to meet a Navy carrier or USMC F-35B’s underway. Right now the latter struggle with the short legs that F-5’s bring as an adversary,” he said.

The Air Force has been increasingly conducting large-scale training exercises in off-shore ranges, and doing so with Navy and Marine assets, including carrier strike groups in the past couple of years. This is being driven directly by the U.S. military-wide push to prepare for a potential future high-end conflict in the Pacific region against China.

A need for adversaries in more places

In the past, Blue Force Technologies highlighted how Fury’s low cost and overall flexibility could offer a way to relatively rapidly inject a diverse array of additional mock opponents into a particular training scenario or just increase the overall volume of adversaries available for an exercise. It has long been clear to the Air Force and others that realistic training for higher-end conflicts demands not only more advanced aggressors, but larger physical areas to train in and the ability to flood those zones with real, representative threats.

In his 2022 interview with The War Zone, Van Timmeren pointed out that between five and 10 Furies could potentially be operated for the same per-hour cost as a single F-35. “You suddenly get the mass that you’re looking for in order to replicate what the adversary could be throwing at us,” which in turn “creates a completely different and immensely more challenging scenario for the operators,” he said at that time.

An uncrewed system like Fury allows for significant additional capacity to be generated in large-scale training events without the need for crewed platforms or pilots to fly them. At the same time, they could still be layered together with crewed aircraft, if desired, as part of a larger threat mosaic.

Perhaps more importantly, a very-low-cost uncrewed system with very limited logistical and infrastructure requirements, as Fury is intended to be, is ideally suited to providing lower-end aggressor support on a more routine basis. Individual fighter squadrons in the Air Force, as well as the Navy and Marine Corps, and other armed forces, often conduct air-to-air training on an almost day-to-day basis, which requires the unit to “self-generate” an opposing force from its own pilots.

“Aside from dedicated aggressor units that exist as specialized units, nobody in a squadron wants to go fly red air,” Blue Force Technology’s Bledsoe said in 2021. The value of those training hours to the adversary pilot are low. He added that this could mean senior instructor pilots, who are often tasked with flying the aggressor mission, could spend more time actually instructing from the ‘blue’ side.

So, the less time friendly jets from units not dedicated to the aggressor mission spend flying red air sorties, the more flying hours they can spend on more beneficial training or operational activities. This also preserves precious airframe hours on fighters, helping to reduce the overall wear and tear on very costly combat aviation fleets.

This will only become a more pronounced issue for the Air Force, among others, as it transitions to a tactical combat jet force made up primarily of fifth and eventually sixth-generation stealth combat aircraft, which have significantly higher sustainment requirements than their fourth-generation predecessors. This reality has recently been underscored by difficulties that the Air Force, as well as the Navy and Marine Corps, have been having in maintaining the readiness of their respective F-35 stealth fighter fleets due to problems in sustaining the F135 engines that power those jets.

At dedicated training bases, where many pilots are learning the basics of their tactical platform, the need for expensive manned aggressors is even less pronounced under many circumstances. Often times, basic intercept training that does not require a high-end asset will be flown ‘in-house’ or by adversary contractors operating old jet trainers or fighters. Fury could potentially accomplish these missions in a more flexible and less costly manner.

Fury’s operational footprint may ultimately be small enough to allow it to be more readily and flexibly moved by trucks on the ground to and from staging bases. This could include smaller airports and airfields with shorter runways and more limited facilities, rather than formal military bases. This would take pressure off of major air bases that are already close to being maxed out operationally, especially during large training exercises. Any issues with integrating unmanned assets into this installation air traffic flow could also be avoided by using smaller airports closer to the training areas.

“There are a number of different transport mechanisms that we’re looking for, because… logistics are the challenge and so we want to maximize the impact of mobility while minimizing the impact on the logistics chain,” Van Timmeren told The War Zone in the interview last week. “So there’s a sweet spot in there that we’re looking at exploring.”

Not just mimicking fighters

Over the years, Blue Force Technologies highlighted how Fury had the potential to be employed in the aggressor role in more novel ways, especially if the drone could remain aloft for a longer period of time.

As an example, in 2022, Van Timmeren described a notional scenario to The War Zone where a group of Fury drones might be playing the part of enemy cruise missiles in an exercise. After they either ‘shot down’ or successfully ‘hit’ their targets, they could fly back to a designated assembly area, ‘regenerate,’ and return to the active exercise zone to act as mock fighters or something else entirely. This would be further enabled by software-defined payloads that could be quickly switched from pumping out emissions and possessing the sensor signature representative of one type of threat to another.

“They [the Furies] all can come out as something else, or stay as cruise missiles. They can climb, ascend, descend, change their profile,” Van Timmeren had said last year. “So you absolutely can mix and match as desired.”

Cruise missiles are a particular area of concern for the U.S. military. Fears have been steadily growing about the threats they pose to U.S. forces abroad in the context of a future conflict and to sensitive military and non-military targets within the United States. Chinese and Russian progress in the development of increasingly more advanced designs, and new platforms to launch them from, such as new very-quiet submarines, has underscored these fears among American officials, as has the war in Ukraine.

The U.S. Air Force is now leading a Department of Defense-wide effort to explore new cruise missile defense options, including the establishment of new domestic surface-to-air missile sites, for protecting targets within the United States. It has already been working to expand its ability to defend against these threats, including through the upgrading of a large number of F-16C fighter jets with new AESA radars. The service previously did the same for a portion of its F-15C/D Eagle fleet, in large part to improve the ability of those fighters to perform the counter-cruise missile mission. The service, in cooperation with the U.S. Army, has also been exploring new and expanded ground-based cruise missile defense capabilities.

“If there’s anything that the war in Ukraine has taught us, is the value of cruise missile defense. And if you look around at what we do for cruise missile training and practice, in the joint DOD force right now, it is not replicative at all what a cruise missile does, as far as radar cross-section, blind profile, etc,” Van Timmeren pointed out last year. “We’re using Learjets or our CAF CAS [Combat Air Force Contracted Air Support] partners to pretend to be cruise missiles. And that’s just not okay.”

“So I think that this is going to open up a whole new market, especially if homeland defense and defense of the Pacific is important to us, cruise missiles are going to be something that we definitely want to be comfortable defending against,” he continued.

Improving air and missile defense capabilities in the Pacific is a major priority for the U.S. military at present. These efforts include plans to significantly expand the defensive infrastructure on or around the highly strategic U.S. island of Guam in the western Pacific, as you can read more about here.

Today, the Navy’s surface fleet constantly trains against the cruise missile threat on a daily basis. This is accomplished by manned aircraft, like the aforementioned business jets, as well as vintage fighter aircraft that pack electronic warfare and radar emission simulator pods. Existing, far less capable drones are also used, but they need to be refurbished and/or reset after each use or are disposed of on their mission. Fury could potentially offer a much less expensive, more adaptable, and threat-representative cruise missile surrogate than these existing solutions, at least for a good chunk of the potential mission profiles required.

Pivoting to become much more than just an aggressor

With Anduril’s acquisition of Blue Force Technologies, the focus on Fury as an aggressor has been replaced by a much broader pitch. The new Fury website explicitly presents the drone as a “high-performance, multi-mission platform” that could be configured to support various mission sets.

Fury has always had obvious potential to be much more than an aggressor, or at least as a starting place for future variants and derivatives optimized for other roles. This is something we raised repeatedly from our earliest interviews with the Blue Force team. And, as Van Timmeren noted, Blue Force Technologies’ original Grackle concept that gave birth to Fury had actually been focused on the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) mission set.

Even before Anduril acquired Blue Force Technologies and began actively promoting the pilotless jet as a multi-mission platform, there had been growing indications the project’s focus had gone well beyond just ADAIR.

Blue Force Technologies’ booth at the Air & Space Forces Association’s 2022 Air, Space & Cyber Conference featured artwork, seen below, depicting a more robust uncrewed combat air vehicle (UCAV) derivative design with a new, stealthy twin v-shaped tail configuration and carrying radar-guided air-to-air missiles under its wings. On the show floor, Van Timmeren told The War Zone that he could not provide any additional details about the rendering at that time.

In its press release regarding the ground test in January, Blue Force Technologies had specifically highlighted how Fury itself could “be adapted for other Autonomous Collaborative Platform (ACP) mission areas.” A notional “YFQ-XX” prototype fighter drone designation was also seen written on the side of the test figure in the picture that was released along with that announcement.

Timing is everything

What has changed since Blue Force Technologies first began shopping the Grackle/Fury concept is that the demand for a lower cost, high-performance combat drone it was told in 2017 didn’t exist does now and in a very big way.

For years, the U.S. military had largely relegated work on highly autonomous uncrewed systems of various types, including advanced uncrewed combat air vehicles, to the realm of experimentation, at least publicly. The War Zone has been calling attention to the worrisome reality of this situation for years now, especially with regard to the development of uncrewed combat air vehicles (UCAV).

There has since been a complete about-face and the U.S. military is very actively pushing to operationalize these kinds of capabilities to support various mission sets. The biggest recent development in this arena that is directly relevant to what is now Anduril’s Fury drone was the Air Force’s announcement last year that it was actively planning around the future acquisition of at least 1,000 Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA).

CCA is part of the Air Force’s larger Next-Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) initiative that also includes separate work on a sixth-generation stealthy combat jet, as well as new weapons, sensors, networking and battle management capabilities, advanced jet engines, and more.

The CCA program is currently centered on the development and purchase of at least one type of drone with a high degree of autonomy primarily intended to work closely together with crewed fifth and sixth-generation combat jets in a so-called ‘loyal wingman’ capacity. The 1,000-CCA acquisition plan is based on a concept of operations that envisions two of these drones being paired with each of 200 future NGAD combat jets, as well as 300 F-35A Joint Strike Fighters.

At the same time, the Air Force has already said that it could acquire far more than 1,000 CCAs and they could be of multiple types intended to take on additional mission sets. The service has a number of separate efforts ongoing that are also expected to feed into the CCA ecosystem, including a separate project ostensibly focused on advanced uncrewed aggressors that Air Combat Command has been running, called ADAIR-UX.

“Air Combat Command is hosting the industry days to build market research and discuss how semi-autonomous adversary air can complement existing adversary air capabilities and be a foundational building block for Collaborative Combat Aircraft prototypes,” ACC’s public affairs office told The War Zone in a statement in October 2022. At that time, ACC also stressed that the command did not see uncrewed platforms fully supplanting crewed aggressors in the future.

Even when it was being pitched primarily as an aggressor drone, the vision for Fury included it offering a lower-risk way to prove out broader concepts of operations for uncrewed aircraft and help gain trust in those capabilities. The U.S. military regularly stresses that the need for operators to gain trust in highly autonomous systems to be able to perform tasks as expected will be key to successfully operationalizing these platforms. Integrating them with crewed assets not just in the air, but on the ground, is also a large part of figuring out how this unmanned air combat pivot will all play out, as is how these drones will be organized into units and where they will be based. You can read all about these issues here.

“I think this aircraft [Fury] is going to present an opportunity for… the Air Force to develop trust. There is no unmanned fighter, you know, out there. And so how does ATC [air traffic control] interact with an unmanned fighter? How does ground control interact with an unmanned fighter? You know, how does the FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] interact with something that’s not a 0.5 Mach UAS [uncrewed aircraft system]? It’s going to perform like a fighter. How do we maintain something [like this?],” Van Timmeren had explained to The War Zone last year. “This is going to be an opportunity in the training environment to learn and grow through all that.”

“The CCA ecosystem can really grow off of what we learn here,” he added.

There is also the Air Force’s secretive Off-Board Sensing Station (OBSS) drone program. General Atomics is currently on contract under that effort to demonstrate a highly modular drone concept, called Gambit, which is centered on a common ‘chassis‘ that uses different airframe designs.

The Air Force has previously identified the service’s Skyborg program, DARPA’s ACE project, and Australia’s Airpower Teaming System (ATS) program as “technology feeders” for CCA.

Boeing has already developed and been actively flight-testing a stealthy drone, now known as the MQ-28 Ghost Bat, for the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) under ATS. The Air Force, through the Pentagon, has also acquired at least one MQ-28 to support its own advanced drone and autonomy test programs.

Uncrewed XQ-58 Valkyries and UTAP-22 Makos from Kratos and Avengers from General Atomics, as well as the X-62A Variable Stability In-flight Simulator Test Aircraft (VISTA) test jet, are also being employed in this research and development effort. VISTA is a heavily modified F-16D Viper fighter and has the ability to directly mimic the flight characteristics of a wide variety of crewed and uncrewed aircraft.

Interest in CCA-type drones extends beyond the Air Force, as well. The U.S. Navy has its own separate NGAD program, which includes work on similarly advanced uncrewed companions for its crewed tactical jet fleets, including the future sixth-generation F/A-XX. The two services are collaborating closely on various aspects of their respective NGAD efforts, including the development of systems that will allow them to seamlessly exchange control of drones during future operations.

There are a host of other advanced drone projects that we know about, and many more are certain to exist in the classified realm, which could be relevant to the CCA effort or similar programs elsewhere across the U.S. military. Just last week, General Atomics announced that it had been selected to build an air-to-air missile-armed drone that fighters and bombers could launch in mid-air and control as part of the next stage of DARPA’s LongShot program.

Even with these examples, the degree to which the overall landscape across the U.S. military has changed when it comes to uncrewed systems and autonomy in recent years cannot be overstated. The entire Department of Defense has fully pivoted to the position that the acquisition of large quantities of advanced autonomous uncrewed platforms is critical.

This was just recently underscored by the Pentagon’s announcement of a new initiative called Replicator last month. Replicator is not a program itself and will have no direct funding, and is more about helping to put new emphasis behind existing projects to help field “thousands” of “small, smart, [and] cheap” autonomous uncrewed systems in the coming years.

“This is about driving culture change just as much as technology change, and about replicating best practices just as much as products so we can gain military advantage faster,” Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks, who is overseeing Replicator, explained during a talk at a conference hosted by Defense News last week. “This doesn’t require a joint program office or re-shuffling deck chairs in any other way.”

The main takeaway here is that the U.S. Air Force, in particular, now has a strategy that outright relies on high-performance and complex unmanned aircraft to overcome major issues it faces with pacing and force structure, especially in regards to China. Drones that seem to have very similar basic attributes as Fury are now likely to be in demand by the hundreds if not thousands in the very near term. Anduril believes it can be a new and disruptive leader in this space.

What a difference just half a decade or so makes.

Fury’s future with Anduril

“I think the bigger point is, all of this is kind of in furtherance of the vision that we’ve had really since the beginning days of our company, which is that the future of military competition is increasingly going to be decided by large quantities of lower-cost autonomous systems in all domains,” Anduril’s chief strategist Brose told The War Zone last week. “And there’s a version of that that’s right for CENTCOM [U.S. Central Command, which oversees military operating in the Middle East], there is a version of that that’s right for Ukraine.”

“The version of that that is going to be right for INDOPACOM [U.S. Indo-Pacific Command] requires systems with the kind of performance parameters that Fury has, longer range, faster speeds, greater payload capacity, greater survivability, but still coming in at that low cost, kind of attritable attribute,” he continued. “So, for us… a lot of the work we’ve done has been building up the underlying software capabilities required to make that vision true… That’s what Lattice for mission autonomy has done and is increasingly becoming… there’s underlying elements… in terms of kind of networking, mesh network management, the kinds of things required to make a world of large quantity, autonomous systems true and viable and effective.”

Anduril plans to make use of Lattice, which it describes as an “artificial intelligence-enabled software platform that enables teams of autonomous systems to dynamically collaborate to achieve complex missions, under human supervision, as well as mesh networking capabilities, together with Fury. Chief strategist Brose told The War Zone that the company would be open to pairing the drone with third-party autonomy software and other systems, as well.

“Lattice for mission autonomy is an incredible piece of software. If the government wants to buy Fury and put someone else’s autonomy and software on it, they absolutely can do that and we support that. Similarly, if they want to buy Lattice for mission autonomy and integrate it into a third-party aircraft that isn’t Fury or another aircraft that Anduril manufacturers, they can do that, as well,” Brose said. “The point for us is optionality and giving the government the ability to compose and recompose different technologies to meet operational needs that are hard to define and rapidly changing.”

Blue Force Technologies had already been able to start maturing the underlying software required to enable Fury’s semi-autonomous capabilities and its flight dynamics before the acquisition.

“In May [2023], we were able to get a whole bunch of playtests done on [the X-62A] VISTA out at Edwards [Air Force Base in California,” Van Timmeren told The War Zone last week. “We actually had our ground control station on the ground – the guys up in VISTA had their hands up in the air and VISTA was receiving commands from our GCS and turning like Fury would. And, so, we’re getting relevant performance characterization from a number of different areas, whether it be ground test and in flight test with a surrogate.”

Beyond Lattice, Brose elaborated in further detail on what the future might hold for Fury when speaking to The War Zone this past Friday. This still includes the aggressor component, but that could just as much end up being a secondary capability that can be used during peacetime on an otherwise fully combat-capable drone.

“Our belief is that there are multiple applications for Fury. Obviously, the aggressor air, ‘red’ air applications… the United States Air Force is getting smaller. We don’t have enough pilots. How you’re going to actually train the Air Force is going to have to change and here, too, I have to believe that autonomous systems are going to be a central part of how we get out of that problem.”

“On the flip side, there’s obviously sort of ‘blue’ and offensive applications for a system like this. Again, multi-purpose. I think in that respect, this is a story that’s still unfolding from the government, in terms of where exactly they’re going. What are the specific opportunities to be able to compete for across the services? … Even if you’re moving in advance of the government, in advance of the requirements process, if it’s a capability that you have convinced yourself is solving meaningful operational problems for the joint force, just move.”

…

“With respect to this specific application, Blue Force has been working on it for four years. They’re well ahead of most of industry, to include Anduril. And to accelerate the existence of a capability that we believe the United States needs, allies and partners need, both for offensive, as well as defensive and training and other mission requirements, this is something … we just need to do.”

Still, Anduril, with its deep portfolio of software, communications, and other enabling capabilities, has a clear eye on the fact that it will take much more than just an air vehicle to make something like Fury meet its true potential.

“The challenge for systems like these is going to be how they scale and how you manage a distributed network, in a tactical environment, likely in a highly contested environment, to be able to keep these systems operating, communicating, connected with one another… So, in this respect, fury would be a node in that network… it would have the computing capability on board to do things like sensor processing and fusion, to be able to make sense of its operational environment, relative to other systems that it would be operating with, manned or unmanned. And then the amount of information that would have to be passed around that network would be relatively small and prioritized based on the operations that that family and systems is performing.”

“So that it enables the kinds of capabilities that are going to have to exist to make this an effective weapon system. The ability to route information dynamically across that network to be able to do things like cross-platform sensor, fusion, automated target recognition, of course, and do all of this as nodes are dropping in and dropping out of the network and the network is scaling and needing to scale to pretty significant numbers.”

Van Timmeren, in his new role at Anduril, separately told The War Zone last week about how excited he was about the new parent company’s “willingness to provide the resources to dramatically accelerate us getting to [first] flight.”

It still remains to be seen exactly when Fury might take to the sky for the first time. What we do know now is that Anduril is planning on making significant new investments in the project, and in the rest of what was formerly Blue Force Technologies to make further use of its specialized experience and knowledge base. This could mean additional advanced drone projects in the future, but for now, the focus is getting Fury into the air.

Disrupting the U.S. defense industrial base

Brose also stressed to The War Zone how Anduril believes core changes to planning within the defense industrial base, and general culture shifts related to it, are just as important as any individual platform, if not more so, if the U.S. military wants to realize its uncrewed future and outpace its adversaries. He also highlighted how the acquisition of Blue Force Technologies, and especially its advanced manufacturing capabilities, is particularly important to the company’s vision in this regard, saying:

“I think this [manufacturing] is going to be a critical part of this story. Obviously, the war in Ukraine has put into high relief the challenges that our traditional defense industrial base has. A lot of that has been driven by government actions over many decades, where we’re not buying enough of the things that we need and then we’re surprised that we’re running out of weapons when we actually get into a fight. I think the important point here is how completely off the mark the defense sector is in terms of what large-scale production really means.”

“So, as an example… the Air Force is now maxing out production of JASSM [the Lockheed Martin AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile]. It’s coming in around, you know, a little over 500 weapons per year, at the cost of about 1.3 million dollars apiece. At the same time, Tesla is producing [4,000] to 5,000 cars per week at the price of $36,000 a car. I concede that JASSM and weapons like it are incredibly complex systems, but it is hard to argue that they are that much more complex and that much more expensive than a Tesla that is going to have human life in it.”

“Again, this gets into a different kind of military system that you can buy at greater velocity and greater scale [which] allows you to begin completely changing your approach to manufacturing and utilizing all of the advances that have also occurred in manufacturing over the past couple of decades. So much of the attention with respect to technology and innovation goes toward artificial intelligence and autonomous systems. But there’s been a revolution in manufacturing as well, which traditional defense industry has also largely been left behind on.”

“And that is an area that Anduril has consistently been pushing on and moving forward. And the prospect of being able to build and field systems in larger quantities, because there is an actual government recognition and government demand for those systems and the necessity of those systems, again, is an incredibly exciting opportunity to do this differently and generate a completely different and superior warfighting capability to the joint force at a much-reduced price.”

…

“Historically, when the Department of Defense has thought about unmanned systems, especially unmanned systems of this size and complexity, they don’t buy very many of them. Whereas I would argue the value of systems like this is only returned when you get to hyperscale. That’s when you really see the knee in the curve in terms of the capability and game-changing effects that a group of autonomous systems like this can deliver on behalf of the warfighter. The challenge that comes along with that is the ability to keep those systems operating in a dynamic network environment with lossy comms, and all of the associated challenges that are going to exist in that highly contested environment.”

Brose continues with the larger potential implications of the rapid changes in the DoD’s strategy towards unmanned systems and projects like Fury:

“The thing that’s exciting about a system like this [Fury] is that it totally breaks the model that the Department of Defense has traditionally thought of in terms of requirements programming, budgeting, sustainment. It inverts it, ideally, in the sense that I’m not going to have a very long RDT&E [research, development, test, and evaluation] period that leads to a relatively small procurement and then decades [of] development.”

“What should happen is, if the Department actually completes the swing on things that they have been talking about, the Deputy Secretary’s announcement of Replicator, Secretary Kendall’s announcement of 1,000s of CCAs. This is the right level of ambition. And they are capabilities that can be procured now or in the very near future. And if they’re procured in large quantities, you begin to create a market that didn’t exist before and, inside of that market, you’ve now created sub-markets for capabilities that, again, previously weren’t able to exist — lower-cost sensors, lower-cost weapons, and things that are incredibly necessary to realize the vision of autonomous air systems in the high-end fight. But also a way of changing the way [the] Defense [Department] accesses the best technology.”

These points are ones that have not been lost on the U.S. Air Force, in particular, which often talks about the almost unsustainable growing costs of advanced crewed aircraft. For instance, the current Secretary of the Air Force, Frank Kendall, has said it expects the unit cost for its future crewed NGAD combat jets to be “multiple hundreds of millions of dollars.”

This, in turn, has prompted significant interest in novel ways to reduce traditional development, acquisition, and sustainment costs, including trying to leverage commercial manufacturing advances. Digital engineering and rapid prototyping capabilities, which Blue Force Technologies had also specialized in, have been another major focus area.

“The Bandit program is about demonstrating ever tighter model-to-hardware prototype development cycles for autonomous collaborative platforms, and this integrated propulsion flowpath test is indicative of that approach,” Alyson Turri, the program’s manager at AFRL, highlighted in a statement accompanying the announcement of Fury’s successful engine run in January. “After making the engine selection in June 2022, the AFRL and Blue Force Technologies team worked to finalize test objectives and procedures concurrently with Blue Force’s hardware build to ensure this full-scale test came together in under six months.”

It is worth noting that the Air Force has begun to push back somewhat on digital design and engineering concepts, at least when it comes to the expectation that they will lead to revolutionary advances in efficiency. In May, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said he believed what these digital tools had to offer had been “over-hyped” in recent years, but that they can still be expected to have a substantial positive impact, as you can read more about here.

At the same time, the argument can and has often been made, as The War Zone has repeatedly highlighted, that the U.S. military cannot continue to use its long-standing processes and expect to field critical capabilities and otherwise foster the innovation necessary to maintain its edge in the long term. When it comes to advanced uncrewed aerial systems with high degrees of autonomy, China’s aerospace industry is increasingly moving towards parity with its U.S. counterparts, if not potentially moving faster in some regards.

Not moving as fast as possible to develop potentially game-changing autonomous systems could prove very problematic in the future. For instance, wargames conducted by the U.S. military, or by independent organizations operating under its auspices, routinely show that relatively low-cost drones with high degrees of autonomy working as networked swarms could be a game changer in any future conflict over Taiwan.

How the Air Force and the Navy will end up moving forward their plans to acquire CCA-type drones and other advanced highly autonomous uncrewed systems (military-wide) remains to be seen. Anduril’s Brose acknowledged that, his company’s vision notwithstanding, it is still very much up to the customer to define the requirements and the acquisition plan. As a concluding thought in his interview last week he told The War Zone the following:

“I think from our perspective, what is very exciting is if the government gets into a model of buying new capabilities more often, buying them at larger scales, not keeping them around for long operations and maintenance periods, but getting rid of them, retiring them and transferring them to allies, partners or others, and buying new again, you are constantly refreshing that technology. You’re creating a market incentive for constant modernization at the platform level, at the mission system level, [and] at the software level.”

“And through the application of open systems architectures, open and extensible software capabilities, digital design, and all the other things that Anduril is bringing to bear in this regard, and Blue Force Technologies was making possible in its own right, you now have an ability to do rapid technology insertion and prevent the unfortunate experience that we’ve had all too often over the past few decades where a prime integrator is able to lock technology down at the platform level, and is incentivized to do so perversely. And the government cannot update these subsystems at the speed that they need to be able to update them to keep those as modern weapons systems.”

“That’s harder to do when you’re talking about fifth and sixth-gen manned aircraft, where you’re only buying a small number of those systems ever. It is a very different problem to be able to work that with autonomous systems, low-cost attritable systems where you can buy new more often, you can buy in larger scales, and you can get openness and constant modernization through the act of procurement. That is, that is incredibly exciting. And, you know, we’ll see where this journey goes.”

Altogether, Fury’s origin story can be viewed as something of a microcosm of a broader evolution in how the U.S. military is changing its views on uncrewed, highly autonomous systems and the way it may end up buying advanced weapons in the future. Anduril’s recent acquisition of Blue Force Technologies is similarly positioned to be an important part of that story, which is still very much in the early stages of being written. At its core, it is shaping up to be a tale about how America’s notoriously rigid defense industrial base will have to change in order to meet future demands. The resulting shifts could very well see many new airframers come into the fold, shattering the current reality in which a dwindling number of ‘prime’ aircraft makers are largely the sole source for frontline tactical aircraft that require decades-long development times and locked intellectual property rights.

The very idea that two somewhat unlikely, but highly creative companies have joined forces in an attempt to change the way the DoD’s tactical aircraft procurement is done via a relevant capability certainly isn’t going unnoticed by the existing power players in the space. This is not just in regards to the threat posed to their own uncrewed aircraft opportunities and initiatives that are also trying to catch the winds of change in their sails, but also due to the glimpse of the changes in the marketplace on the horizon that it foreshadows.

Still, Anduril has a lot to prove when it comes to Fury and making what was once a small team’s ambitious dream into an operational reality, but it would be hard to argue that their timing could be any better for making that happen.

And with that, it seems clearer than ever that Fury’s story is still just beginning.

Contact the authors: joe@thedrive.com and tyler@thedrive.com