Of the many disparities between U.S. and Communist airpower in the Vietnam War, among the most striking was the almost total lack of air-to-ground capability possessed by the North Vietnamese. In contrast to the large-scale and complex air assaults flown by U.S. warplanes, the Vietnamese People’s Air Force, or VPAF, was almost entirely committed to missions in defense of the North. But one highly notable exception took place 50 years ago this week, when VPAF MiGs flew a daring raid against U.S. Navy warships on station in the Gulf of Tonkin — it would be the only such attack against American warships during that long conflict.

The planning for what was to be a bold attempt to strike a blow against the overwhelming U.S. naval power in the region began in 1971. Since VPAF MiG pilots had, until now, concentrated on attacking U.S. aircraft in the air, special training would be required to stage this new kind of mission. From a total of 10 MiG-17F Fresco pilots selected from the 923rd Fighter Regiment, six were eventually judged capable of flying anti-ship missions. At least one of their instructors was a Cuban, known only as “Ernesto.”

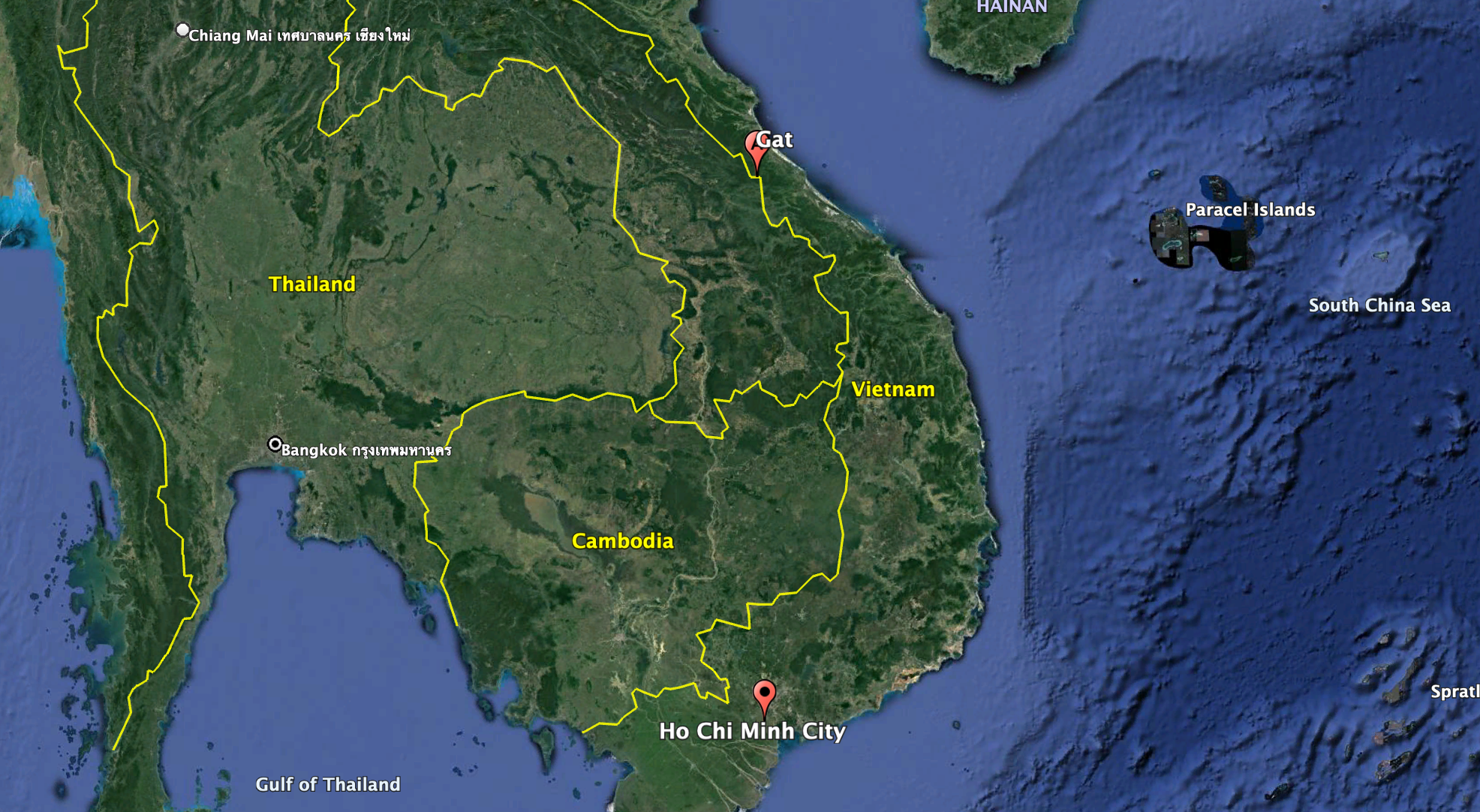

Since the attack would be taking place outside of the VPAF’s usual operating area, a new airfield had to be constructed, in secrecy, at Gat, in Quang Binh province, on the border with Laos. Meanwhile, a radar unit was established close to the port of Nhat Le, from where the positions of U.S. Navy warships in the Gulf would be monitored.

By April 18, 1972, the VPAF was ready to put its plan into action. A pair of MiG-17s, specially adapted to carry bombs, took off from their usual base at Kep, northeast of Hanoi. After a stopover at Gia Lam in the North Vietnamese capital, and at Vinh, the two ferry pilots arrived at Gat. Here, according to some accounts, the silver-colored jets received a hastily applied camouflage scheme.

Shortly before midnight on April 18, the radar at Nhat Le picked up four U.S. warships that were approaching the North Vietnamese coast around Quang Binh before taking up station between six and nine miles from the shore.

By the morning of the 19th, there was another group of two warships in the area, but VPAF hopes of launching an airstrike had to be abandoned due to heavy fog. By the afternoon another group of three U.S. warships had been identified.

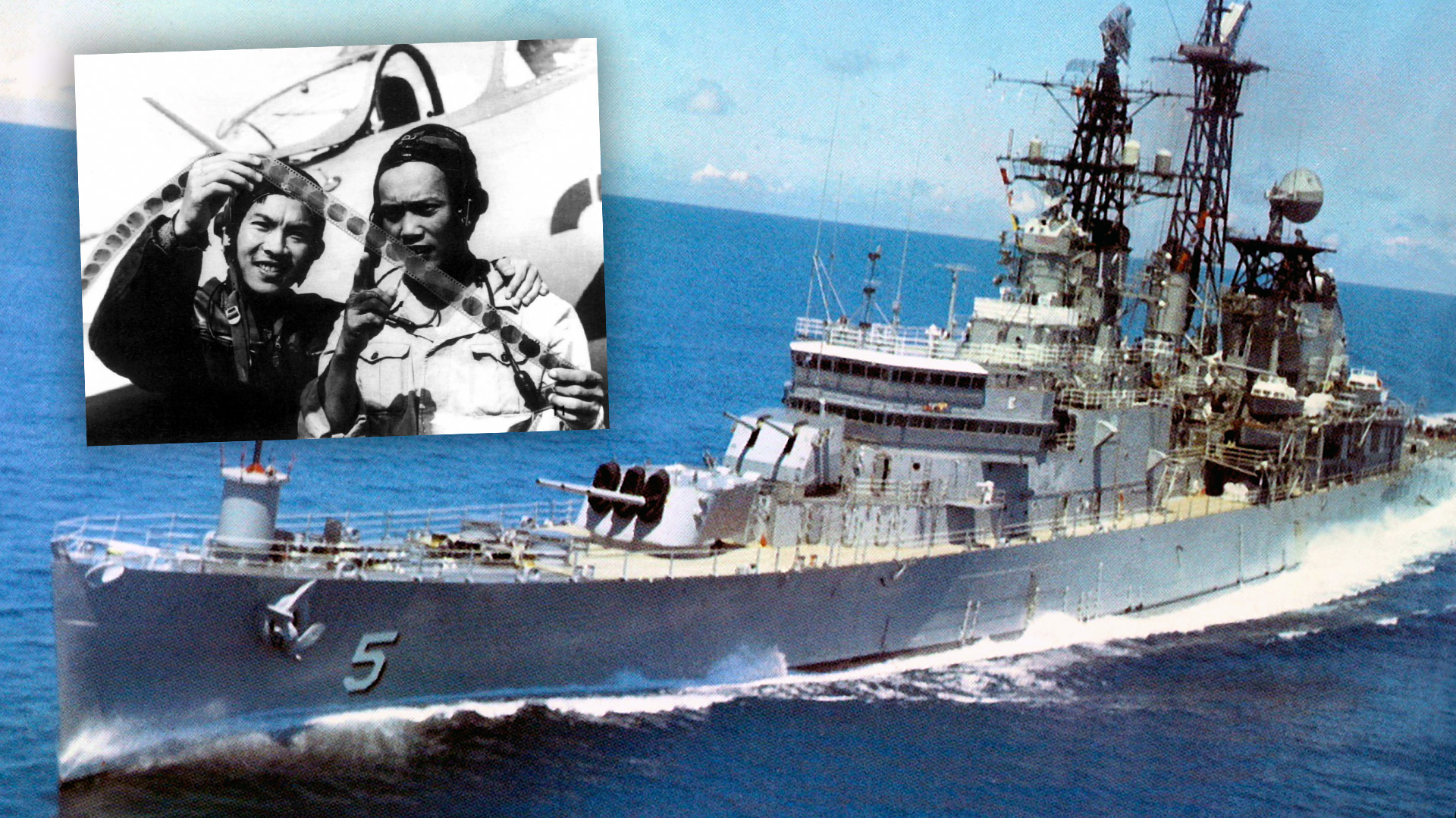

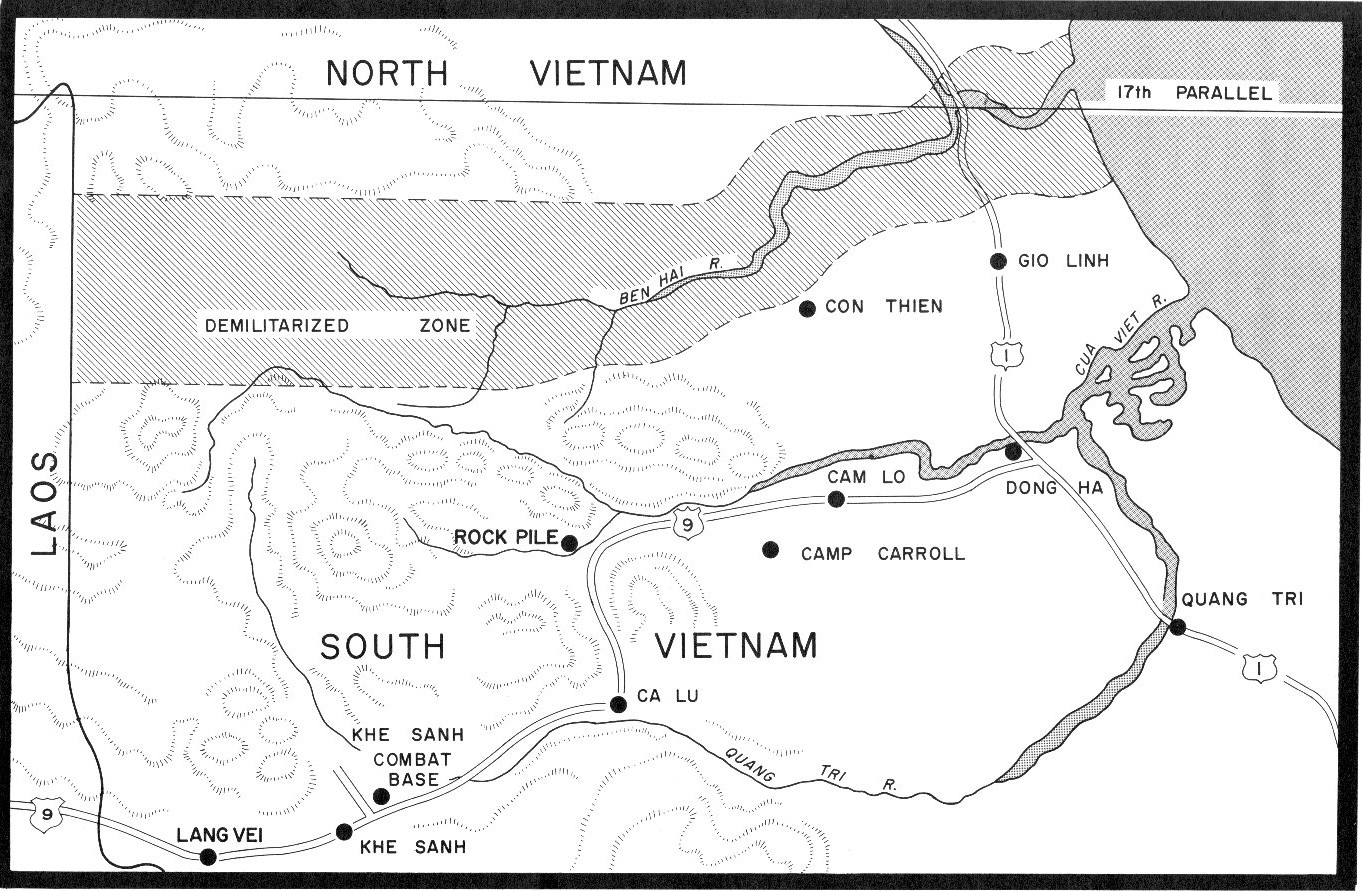

Finally, at 4:05 PM local time, the two selected pilots, Le Xuan Di and Nguyen Van Bay, were given orders to take off. Aware that they themselves could soon be targets for the U.S. Navy once their presence was detected, they flew low toward a hill close to the coast before making a turn to the right. From here they could see what appeared to be puffs of smoke from the warships, indicating that they had begun to engage targets along the coast. U.S. accounts record that the warships were striking positions close to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), near the 17th parallel, the provisional border between North and South Vietnam.

The flight leader, Le Xuan Di, reported to the ground controllers that he had sighted two U.S. Navy warships at a distance of around six or seven miles. Unknown to him at the time, one of the vessels was the USS Higbee (DD-806), a Gearing class destroyer. With the ships in sight, the VPAF pilots were given permission to launch their attack.

Speaking to historian Istvan Toperczer, Nguyen Van Bay recalled:

“Over the sea, Le Xuan Di turned to the left toward the USS Higbee and increased his speed to 800km/h, while aiming at the ship. At a distance of 750 meters, he released his bombs and broke to the left. Both of the 250-kilogram bombs hit the ship.”

Le Xuan Di reported his success to ground control and touched down at Gat at 4:18 PM. Landing too fast, his jet overran the end of the runway and ended up in the arrester barrier. Neither pilot nor jet was harmed.

While Le Xuan Di had prosecuted his attack, Nguyen Van Bay had flown on, toward the Dinh river, where he spotted another two ships to the northeast of those that his flight leader had attacked. By the time he’d seen them he was too close to mount an attack and had to make a second pass. He also dropped his two 250-kg bombs 750 meters from one of the warships, which turned out to be the Galveston class light cruiser USS Oklahoma City (CLG-5).

“Le Xuan Di asked me on the radio: “All right?” I answered, “Not really,” since I thought I had missed my target, After returning to base at 1622 hours, I was told that a 30-meter-high column of smoke was seen out at sea, and later something burst into flames.”

The two attacks had indeed been pressed home with accuracy, with both the USS Higbee and the USS Oklahoma City having been hit.

On the Higbee, the superstructure sustained serious damage, while the rear gun mounting, with its two 5-inch guns, was completely destroyed. The damage also affected the destroyer’s steering and propulsion. Four sailors who’d been outside the turret at the time of the attack, due to an earlier ‘hang fire’, in which a round gets jammed in the gun, were wounded. The Higbee was repaired at Subic Bay in the Philippines and was finally decommissioned in 1979.

The Oklahoma City, which was the flagship of the Seventh Fleet, received only minor damage to the stern, although this was initially attributed to shore fire.

On the U.S. side, there were claims that a MiG was shot down during the raid by a Terrier surface-to-air missile fired from the Belknap class destroyer-leader USS Sterett (DLG-31). While this doesn’t tally with the Vietnamese account, the same cruiser reportedly detected three, not two MiGs, approaching the U.S. warships. There are also reports that Sterett shot down an SS-N-2 Styx anti-ship missile during the incident, although there is no evidence that this weapon had been delivered to North Vietnam as of 1972.

In another discrepancy between U.S. and Vietnamese histories, the American accounts describe North Vietnamese torpedo boats and shore batteries being involved in the action on April 19. There are claims that the Sterett successfully engaged two suspected North Vietnamese torpedo boats later the same day. However, the Vietnamese only acknowledge that these additional naval assets became involved several days later, on the 27th.

U.S. retaliation for the anti-shipping strike came later the same day, with an attack on Dong Hoi Air Base. Then, apparently after discovering its location, the airfield at Gat was hit the following day, with one MiG-17 there being damaged.

While the VPAF attack had been broadly successful, especially considering it was the first of its kind, there were no follow-ups. Partly, this was because of the Americans stepping up raids on military targets, railways, and other infrastructure in the North, which meant the MiGs were tied up on defensive duties once again. The decision was made to concentrate the fighter force, including the MiG-17s of the 923rd Fighter Regiment, for the protection of Hanoi and Hai Phong. Before long, they would be clashing with U.S. aircraft in some of the biggest aerial battles of the war.

Nevertheless, for the North Vietnamese, the attack on the Higbee and Oklahoma City was of enormous propaganda value, demonstrating the will and the capability to strike back against the might of the U.S. Navy. This was, after all, the first time since World War II that the Seventh Fleet had come under attack from the air.

In the history of the Vietnam War, the anti-ship attack by Le Xuan Di and Nguyen Van Bay is now little more than a footnote, but its significance at the time, especially as a morale-booster to the communists, should not be understated. Reflecting its continued importance in the Vietnamese account of the war, the Bay’s MiG-17 from the April 19, 1972 raid is now preserved at the VPAF Museum in Hanoi.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com