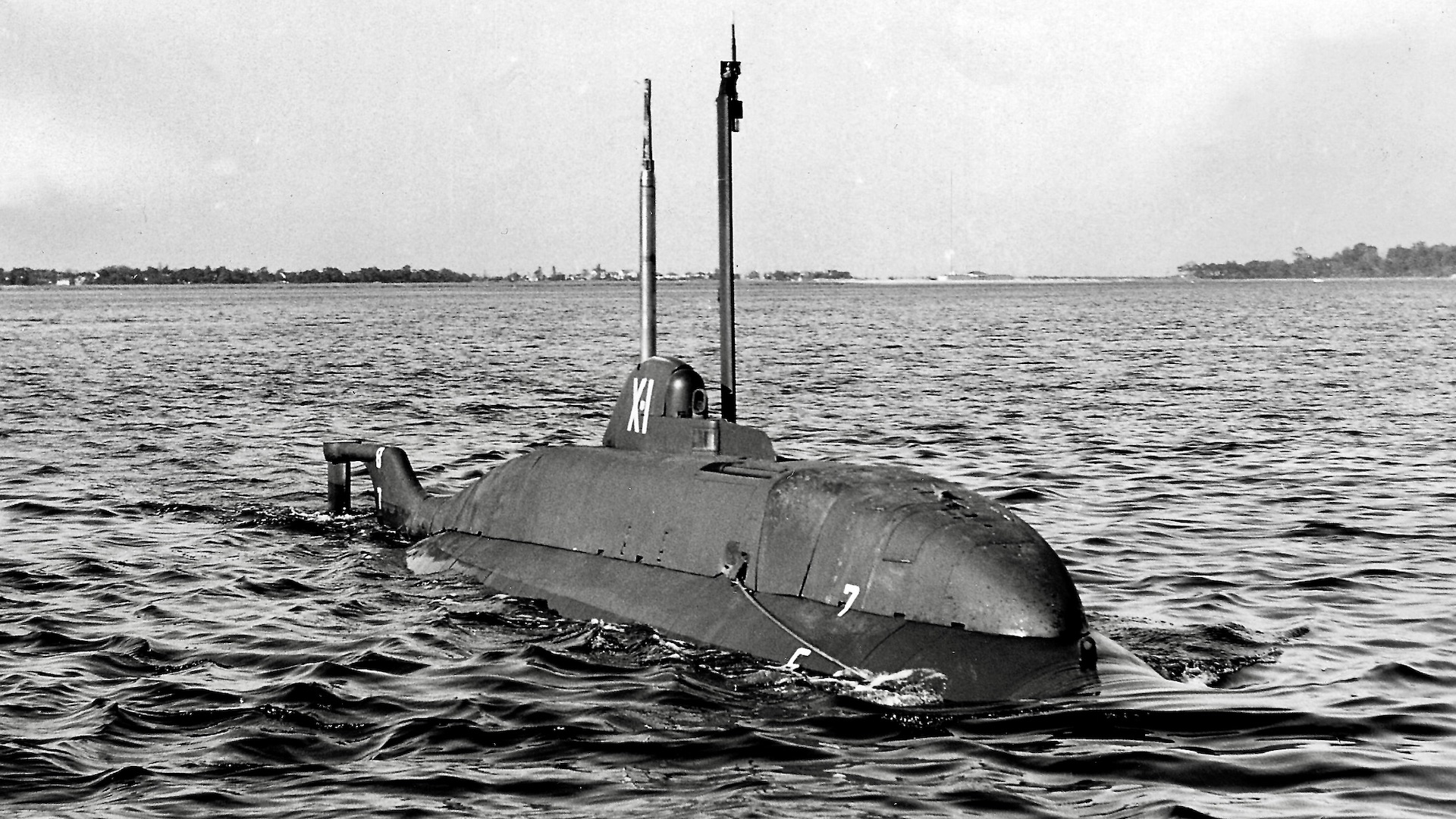

On September 7, 1955, the U.S. Navy’s first midget submarine – USS X-1, or SS X-1 – was launched at Oyster Bay, Long Island. Archival footage of the launch, where the diminutive vessel can be seen cruising past the Balao class submarine USS Bergall (SS-320), may seem comical. Yet the development of the midget submarine – midget submarines meaning small displacement submarines with their own propulsion system that can be operated by a handful of crew – represented something of a novelty for the U.S. Navy at the time.

Inspired by existing (notably British) midget submarines, USS X-1 was designed to bolster U.S. coastal defense, particularly against adversary submarines, in the 1950s. In order to trace the development of USS X-1, we need to look back to the use of midget submarines in wartime.

During World War II, with its submarine patrols covering large areas of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, the U.S. Navy had little reason to explore midget submarine capabilities. Yet with the fall of the Axis powers, as naval analyst H. I. Sutton notes, examples of such ‘sneak craft’ fell into American hands.

German Biber and Seehund midget submarines, as well as Italian Maiale human torpedoes, became available to inspect and, following the success of British midget submarines of the period, the U.S. Navy began to look more closely at the idea of creating its own midget submarines.

The utility of midget submarines as reconnaissance and surveillance craft was not lost on the Navy during the war, it should be noted. Five Type A midget submarines, for example, were used by the Japanese Navy the night before the Pearl Harbor raid of December 7, 1941, in order to provide reconnaissance. At least one of the Japanese Navy’s midget submarines successfully entered the harbor, before being sunk by USS Monaghan (DD-354).

Indeed, America’s very first submarine built in 1775, the Turtle, a proto-midget submarine in its own right, was also originally designed for covert operations, specifically in attaching explosive charges to Royal Navy ships during the Revolutionary War. In many ways, the U.S. Navy was harking back to the granddad of midget submarines in its decision to develop what eventually became USS X-1.

Geni via Wikimedia Commons

Initial efforts by the Navy to develop its own midget submarines began in the late 1940s. Owing to the success of the Royal Navy in deploying this type of vessel, the U.S. Navy was briefly loaned a British XE class midget submarine, XE-7, in 1950 for testing purposes. 12 XE class submarines came into Royal Navy service in 1944, designed for operations in the Asia-Pacific theater. These were improved versions of the X class midget submarines, built between 1943-44 – several X class midget submarines were famously used in Operation Source, the Allied effort to neutralize the German battleships Lützow, Tirpitz, and Scharnhorst, in September 1943.

The Royal Navy went on to build four more midget submarines between 1954-55 based on the XE class, which were known as the Stickleback class.

XE-7 was principally used in harbor defense drills off the U.S. East Coast while on loan to the Navy. As Sutton highlights, the vessel retained its Royal Navy crew as Navy Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) practiced locking out of the ‘wet and dry’ chamber. While XE-7 was only on temporary loan, serious consideration was given by the Navy to permanently leasing XE-7’s sister ship, XE-9, from the Royal Navy, but this never occurred.

Although it was envisaged that the Navy would eventually have four of its own ‘X craft’ midget submarines – with plans for their construction having been drawn up in the late 1940s – the project was ultimately scaled back to just one vessel.

USS X-1, the lone submarine to emerge from the project, was built by the aerospace manufacturing company Fairchild Aircraft during the mid 1950s. The vessel was laid down on June 8, 1954, at Deer Park, Long Island, by the Engine Division of Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corp. As we have seen, the vessel was launched on September 7, 1955, at Oyster Bay, Long Island. USS X-1 was subsequently delivered to the Navy just a month later on October 6. On October 7, the submarine was placed into service, with Lieutenant Kevin Hanlon at its command.

In terms of design, USS X-1 featured a number of similarities to the Royal Navy’s X class. Proportionally, the two types of midget submarine were broadly similar, bar USS X-1’s larger beam and draft. USS X-1 ran a total length of around 50 feet, a beam of roughly seven feet, and a draft just over six feet, whereas the general characteristics of the Royal Navy’s X class were as follows: roughly 51-52 feet in length, roughly six feet for the beam, and around five feet for the draft.

The decision to increase the size of USS X-1’s hull was made in order to improve operational conditions, affording more space when it was operated by two individuals. Improvements were also made in order to allow the vessel to be operated by a single man, with duplicate controls and multiple periscopes installed. USS X-1 also featured a more rounded bow, while hydroplanes were also added in order to improve the vessel’s maneuverability. The vessel also included a diver lock-out chamber.

Arguably the main distinction between USS X-1 and its Royal Navy counterparts relates to its engine. Unlike the standard diesel engines of the X class and XE class, USS X-1 featured a more advanced, closed-cycle hydrogen peroxide diesel engine, similar in principle to the engine on the German Type-XVII coastal submarine. When submerged, USS X-1’s engine relied on the catalytic decomposition of the hydrogen peroxide to generate oxygen (on the surface, a small air inlet was used to operate the engine).

The hydrogen peroxide – a colorless liquid that is often used as a bleaching agent in high quantities and can cause irritation to the eyes, nose, skin, and throat if ingested – was transported onto the vessel in rubber bags, surrounded by seawater. In using hydrogen peroxide, it was envisaged that USS X-1 would be able to travel at faster speeds without the need to resurface.

When the vessel was placed into service in October 1955, it began work in a research capacity in order to test the Navy’s ability to defend harbors against small, adversary submarines. The vessel was also designed for more offensive purposes – principally, as a means of attacking enemy ships using its side-mounted charges which, according to Sutton, would be dropped below the target vessel.

While the Navy Underwater Demolition Teams were interested in utilizing midget submarines for beach reconnaissance, with hopes for four X-1 submarines in support of UDT-2 (which, along with UDT-1, was one of the original UDT groups formed during World War II), hopes for multiple midget submarines were dashed by procurement politics. U.S. Submarine Force, unhappy with the decision of providing UDT groups with their own dedicated submarines, only agreed to one midget submarine being built under the condition that USS X-1 would also be a Submarine Force vessel.

Ultimately, USS X-1’s use of hydrogen peroxide proved to be near fatal. On May 20, 1957, its hydrogen peroxide bags blew up. No personnel were injured in the explosion, thankfully, but the blast was significant enough that the vessel’s entire bow section was blown off entirely. As a result, it was refitted with a regular diesel-electric drive engine.

By this stage, however, with focus having swiftly moved towards nuclear-powered submarine technology, the desire to keep USS X-1 as an active service vessel waned. On December 2, 1957, X-1 was taken out of service and inactivated in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After being towed to Annapolis, Maryland, in December 1960, it was reactivated (and painted in vivid colors) in order to perform experimental duties for Submarine Squadron 6 at the Small Craft Facility of the Severn River Command in Chesapeake Bay. USS X-1 was taken out of service for good on February 16, 1973. In April of that year, the vessel was transferred to the Naval Ship Research and Development Center, Annapolis, and by July it was slated for use as a historical exhibit. USS X-1 is now preserved at the Submarine Force Museum at Grotton, Connecticut.

Although USS X-1 was something of a novelty for the U.S. Navy in the immediate postwar period, the legacy of its midget submarine efforts can be seen into the latter twentieth century and even the twenty-first century.

For decades, U.S. Navy SEALS have used self-propelled ‘wet’ SEAL Delivery Vehicles (SDV), meaning that passengers must wear wetsuits and breathing apparatus due to the lack of a pressurized hull. Other small self-propelled underwater vehicles used by the Navy in the latter twentieth and early twenty-first centuries include, for example, the deep-submergence rescue vehicles DSRV-1 Mystic and DSRV-2 Avalon. Both were launched in the 1970s but were retired from service in 2008 and 2000, respectively.

More recently in 2016, it was revealed that U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) awarded Lockheed Martin a $236 million contract for various ‘dry combat submersibles’ (DCS) to support the U.S. Navy SEALs. Five DCS were delivered by Lockheed Martin between 2018-2022, with indications that upgraded versions could be procured by SOCOM in the future.

Furthermore, the general idea of using smaller underwater submersibles has come back into vogue of late with the advent of unmanned underwater vehicles (UUV). As The War Zone has reported on extensively in the recent past on what is shaping up to be a revolution in undersea warfare via increasingly advanced uncrewed platforms. In fact, it’s very possible that these types of systems will provide a defensive screen along America’s coasts and around key territorial waters abroad, just like the X-1 was supposed to do, sometime in the not-so-distant future. This would provide a particularly fascinating legacy for the Navy’s little unwanted submarine of the early post-war age.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com