On October 30, 1944, during World War II, the submarine USS Salmon endured near-catastrophic levels of damage, and survived to tell the tale.

The deformation of Salmon‘s hull, resulting in major flooding, was caused by depth charges being deployed by Japanese forces. The extent of the damage “can be considered one of the most serious to have been survived by any U.S. submarine during World War II,” the Navy indicated in a subsequent report. How Salmon ended up finding its way out of that position is a truly remarkable story.

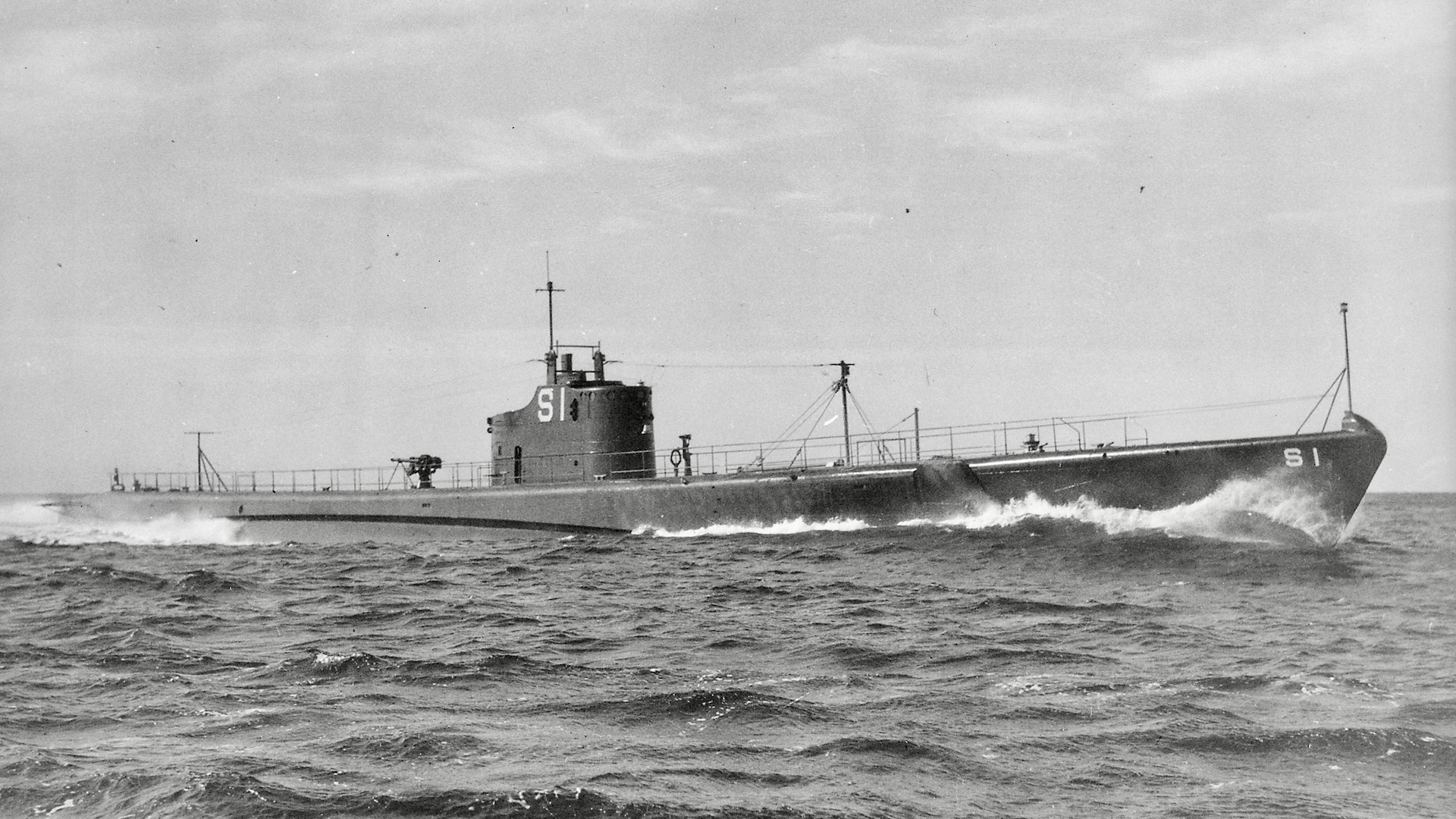

The lead vessel in its class of diesel-electric submarines, USS Salmon was built by the Electric Boat Company out of Groton, Connecticut. The vessel was launched in June 1937 and commissioned in March 1938. In terms of its specifications, the submarine’s standard/surfaced displacement was 1,458 tons, and its submerged displacement was 2,233 tons. It measured some 308 feet long, with a beam of just over 26 feet.

Powered by four Hooven-Owens-Rentschler nine-cylinder diesel engines and four high-speed Elliott electric motors, Salmon was able to achieve a top speed of 21 knots (roughly 24 miles per hour) surfaced or nine knots (roughly 10 miles per hour) when submerged. The boat’s maximum depth was rated at 250 feet. In terms of armament, it carried 24 torpedoes, fired from eight 21 inch torpedo tubes. Salmon boasted a Mark 9, four inch .50 caliber main deck gun and four machine guns for use when surfaced.

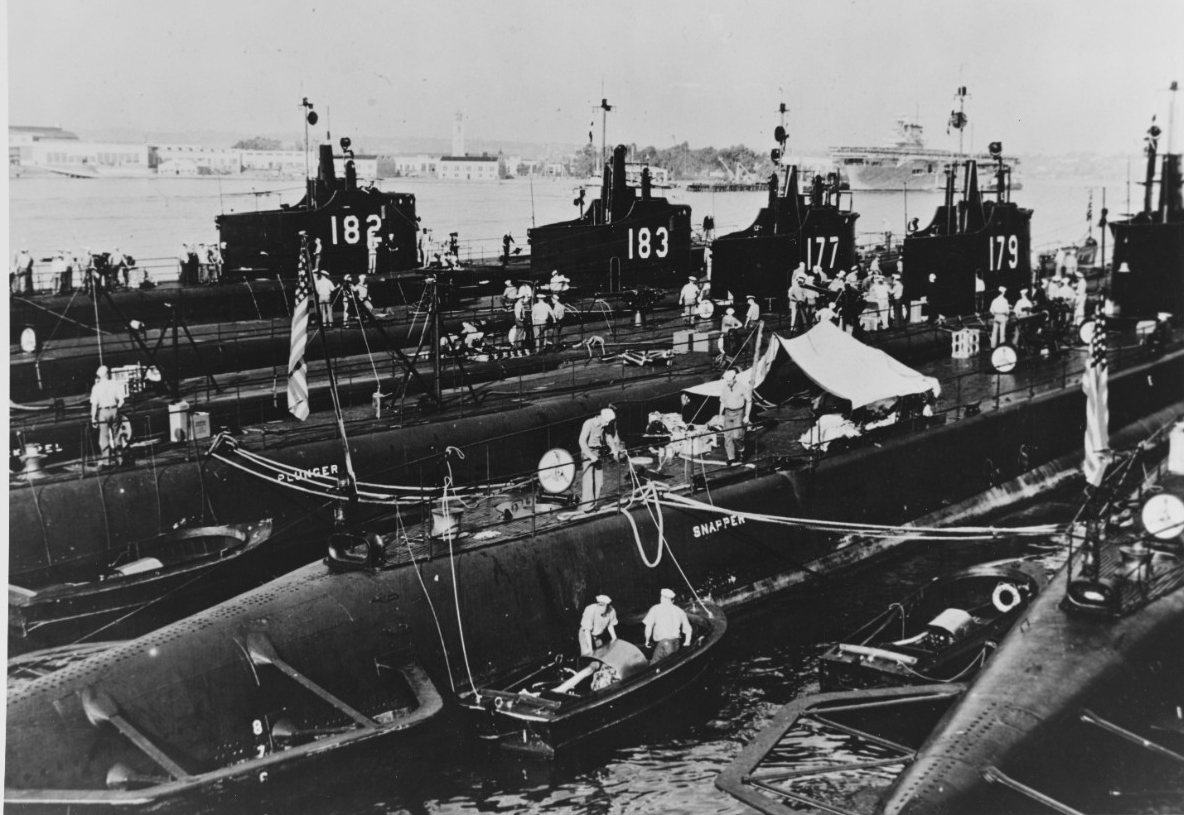

Salmon operated along the Atlantic coast as part of Submarine Division 15, Squadron 6, of the Submarine Force until late 1939. From there, as the Division’s focus began to shift to the Pacific, the boat operated off the west coast of the United States throughout 1940 and much of 1941. In November 1941, it arrived in Manila in the Philippines, then a U.S. colony, along with fellow Salmon class submarines USS Skipjack and Sturgeon, the Sargo class submarine USS Swordfish, and the submarine tender USS Holland. This was in order to bolster defenses in the archipelago.

It was during the boat’s eleventh, and final, wartime patrol that it sustained the huge levels of damage. Departing Pearl Harbor on September 24, 1944, Salmon arrived at Saipan, the largest of the Northern Mariana Islands, on October 3. The next day, it sailed with the Gato class submarines USS Silversides and Trigger, as part of a coordinated ‘wolf pack’ against Japanese shipping vessels. The pack’s designated patrol area was along the eastern boundary of the Ryūkyū Islands, on the southern approaches to the Japanese home islands. It was not until October 30, however, that any suitable targets were sighted. The events of that day are well-documented in Navy records.

At around 04:01, on October 30, Salmon established radio contact with Takane Maru — a 10,021-ton Japanese merchant tanker sailing southwest of Toizaki, Kyushu — while patrolling on the surface. Takane Maru was escorted by four Imperial Japanese Navy anti-submarine frigates. Salmon began closing down the ship, and by dawn, it was some 10,000 yards from the target group.

Throughout the morning and early afternoon, Salmon proceeded to chase the tanker — an endeavor made difficult by Takane Maru’s high speeds, frequent changes of direction, and rain squalls in the area. At 16:20, Salmon noted a large explosion in the tanker’s stern, a result of a torpedo attack by Trigger. Takane Maru appeared to stop shortly afterwards, and the frigates began deploying depth charges.

At around 17:40, Salmon began closing the range for an attack, with the tanker immobilized some 24,000 yards (72,000 feet) in the distance and drifting in the wind in a southwesterly direction. The four frigates were at this stage patrolling roughly 1,200 yards (3,600 feet) on both sides of the tanker. At 18:23, having closed the range to around 8,000 yards (24,000 feet), Salmon submerged and commenced its attack approach.

At 20:01, from a range of some 3,300 yards, Salmon fired four torpedoes at Takane Maru, two of which struck the tanker and detonated. At the time of firing, the submarine was at a periscope depth of 64 feet. Straight after firing the torpedoes, it swung right in order to bring its stern tubes to bear should another salvo be necessary. However, whether due to the firing of its torpedoes or due to sonar detection, two of the frigates headed straight in Salmon’s direction, forcing her to dive.

When Salmon reached a depth of 310 feet, at 20:13, the frigates began launching the first of roughly 30 depth charges, in four patterns of six to eight charges. As Cmdr. Harley K. Nauman, Salmon’s commanding officer, stated:

“The conning tower vibrated up and down so violently that I thought the ship was going to shake herself apart. I remember bending my knees to ease the shock.”

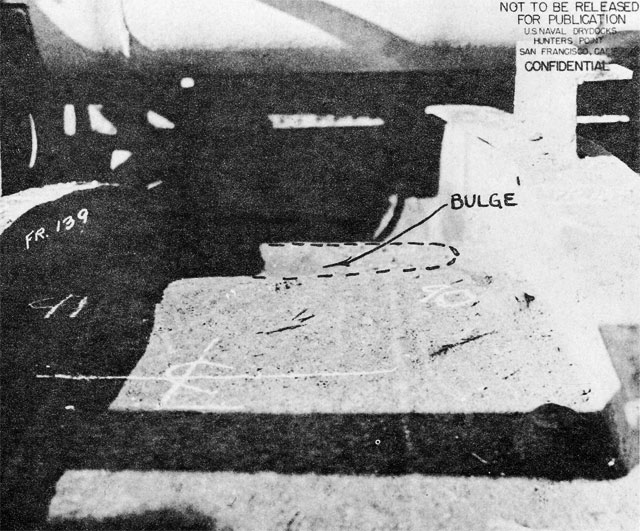

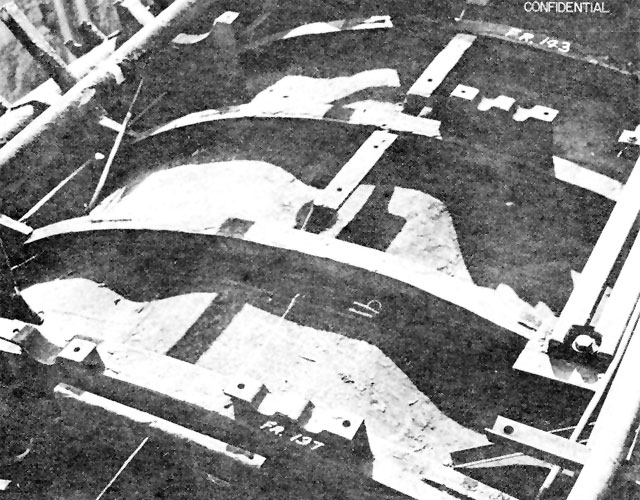

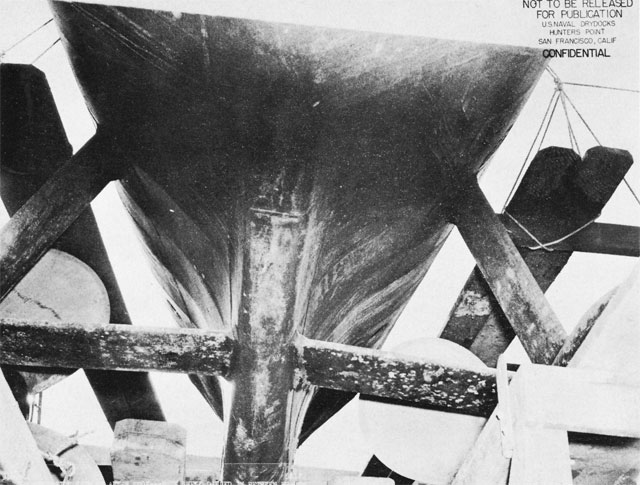

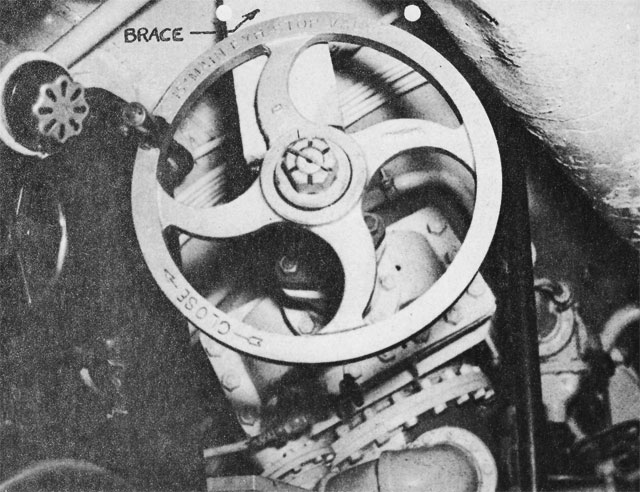

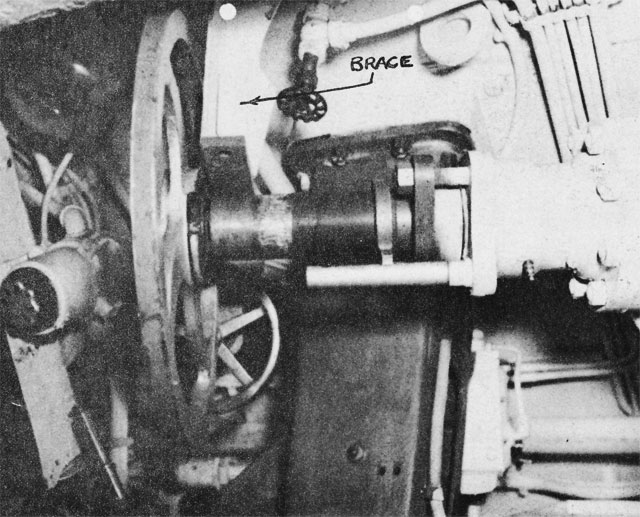

Damage to Salmon as a result was incredibly severe. Its pressure hull was distorted in areas, and leaking occurred in various places — the most serious of which developed in both engine rooms. Moreover, the impact of the depth charges caused its stern planes to become jammed in full dive position. Images subsequently taken of the damage by the Navy can be seen below.

This, combined with added weight due to flooding, resulted in crew members quickly losing depth control. Despite attempts to mitigate its descent, Salmon oscillated up and down several times, and went on to record a reported depth of 578 feet at one stage, which was measured in the control room. As such, the roughly 20-degree up angle of the submarine when that figure was recorded increased the submergence at the after end of the pressure hull — resulting in a depth of just over 600 feet at the after bulkhead. At this depth, the collapse of the pressure hull would have been likely.

At 20:30, after 17 minutes of attempting to surface, Nauman evaluated that there was no other option but to blow the emergency ballast tanks and force Salmon to the surface, despite not knowing the location of the Japanese frigates.

Salmon ended up some 7,000 yards (21,000 feet) away from all four escorts on the surface and was undetected by the frigates for a half hour, which were still deploying depth charges near the original attack scene. This precious time allowed crew members to perform damage control and man the deck guns. By 20:50, numbers three and four main engines were working and, 10 minutes later, all ballast tanks were blown, removing the list and increasing freeboard.

Detecting Salmon at 21:00 from a distance of around 5,000 yards (15,000 feet), one of the Japanese frigates illuminated the submarine and began firing salvos. From 21:15, a frigate fired repeatedly at the boat, but scored no hits. At 21:30, Salmon’s crew delivered radio notifications to Silversides and Trigger of their boat’s position and condition. As it turned out, a total of six other U.S. submarines were in the immediate vicinity, and attempted to deter the Japanese frigates from firing on Salmon via radio communication.

By 24:00, however, one of the escorts attempted to close the range between Salmon — passing its port beam at roughly 2,000 yards (6,000 feet). The two vessels exchanged machine gun fire, without successful hits, and the submarine was then able to take cover in a southwesterly rain squall.

Sensing the time was right to make a stand, Salmon charged towards the frigate, conducting a surprise attack. Passing the Japanese vessel at a distance of some 50 yards (150 feet), the submarine peppered it with machine gun fire before returning to the rain squall. At midnight Salmon was joined by Trigger, Silversides and the Balao class submarine USS Sterlet. From around 00:45 on October 31, all contact with the frigates was lost. Salmon made full speed, around sixteen knots, towards Saipan on three engines — a journey not without trepidation — and eventually moored at Tanapag Harbor, Saipan, on November 3.

During said journey, Salmon was stalked by both Japanese submarines and planes, but was protected by the U.S. submarine screen as well as by U.S. aircraft from above. On November 1, for example, a Japanese Kawanishi H8K2 Type 2 Emily flying boat was detected and shot down by Lt. Guy M. Thompson Jr. of Patrol Bombing Squadron (VPB) 116 while covering Salmon on the sub’s journey to Saipan.

After receiving repairs at Saipan, the submarine proceeded via Pearl Harbor to the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco, California, arriving on December 2. Following an inspection by the Board of Inspection and Survey, it was decided that Salmon should receive minimum damage repairs and be used as a training and experimental submarine. Later in October 1945, it was recommended by the Chief of Naval Operations that any further repair work should be halted. Salmon was subsequently decommissioned on April 4, 1946, and later scrapped.

However, before this occurred, Salmon’s crew received the Presidential Unit Citation (PUC) — a ribbon awarded on or after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and still currently awarded, to units across the U.S. military for “gallantry, determination, and esprit de corps in accomplishing…[their] mission under extremely difficult and hazardous conditions.”

Given the events of October 30, 1944, this honor was undoubtedly justified.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com