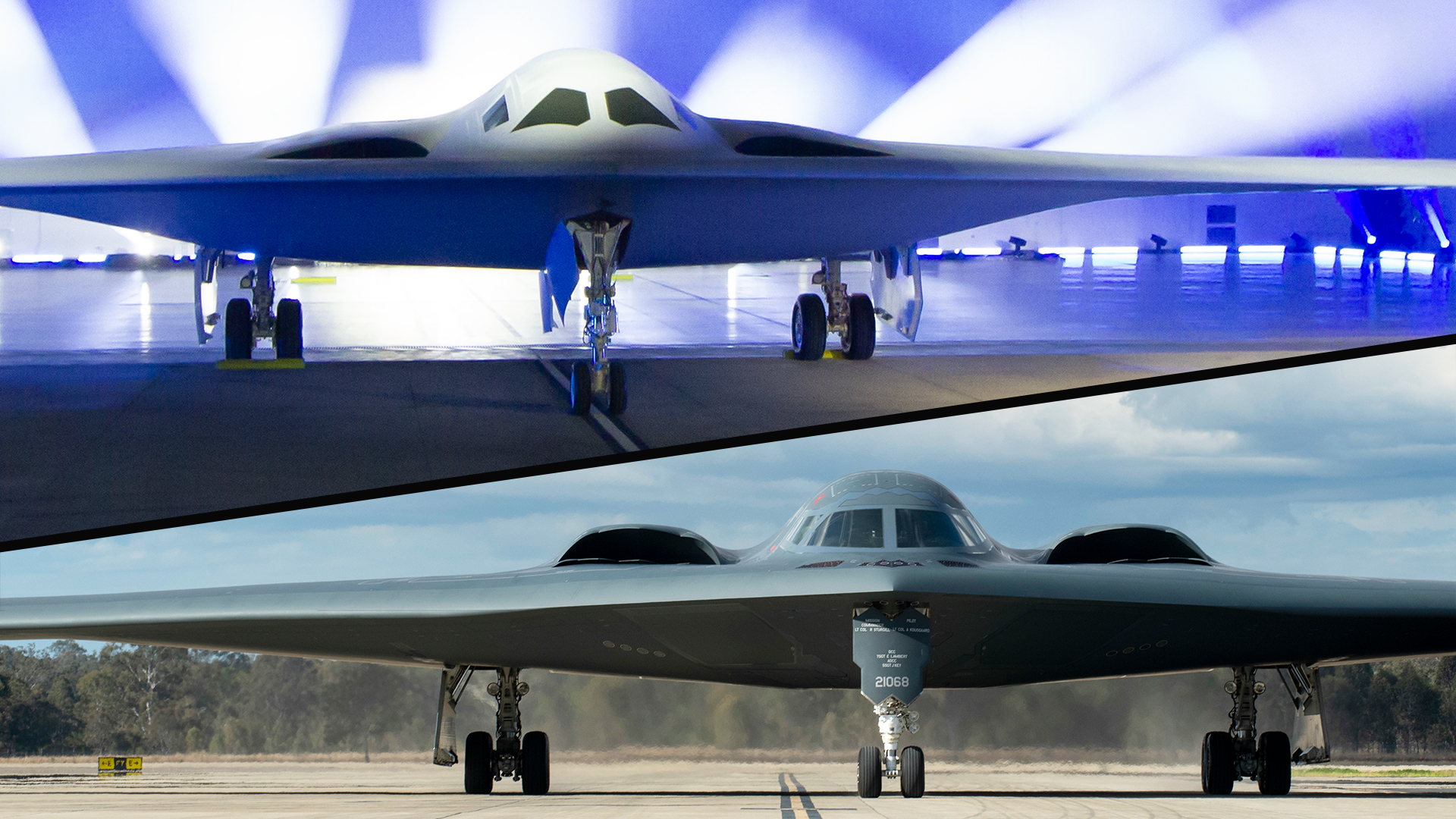

Immediately following the glitzy rollout of the B-21 Raider at Northrop Grumman’s secure facility at Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, the hot takes started piling up. “It’s just an updated B-2 Spirit” and “B-2 2.0, big deal” quickly became par for the course on social media. I received a ton of inquiries from people genuinely asking if this is the great leap forward it was billed as or if the B-21 appeared to be just a ‘rehashed Spirit.’

The answer to those types of questions is, well, complicated, but not in a bad way.

Yes, in some ways the B-21 is a ‘B-2 2.0’ — that’s a marvelous feature, not a bug — and in other ways, it isn’t a ‘B-2 2.0’ at all. It is this unique mix of attributes that makes the B-21 program, and the design that has come of it, so promising.

Here’s why.

Back To The Future

The B-21 has a roughly similar configuration to the B-2, which is evident when viewed head-on. That was always more or less a given. There has been plenty of art released officially on the B-21’s basic design, although until the rollout, fine details were lacking.

The fact is that when it comes to bomber-sized flying wing low-observable designs, there are simply only so many ways to skin a cat. For those less versed in the topic, maybe they expected something even more exotic or even completely different from the B-2 altogether. Most people’s understanding of modern air combat is dictated by Hollywood, so sure, some supersonic super bomber may have been more visually satisfying, although it would have been far less relevant.

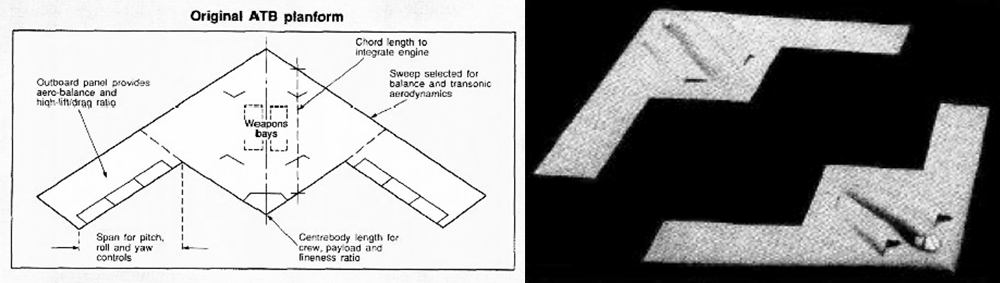

The B-21 doesn’t just look a bit like the B-2 head-on. As we were the first to highlight over five years ago, the B-21’s planform, at least how it is depicted in all art released to date (this could change as we see more of the aircraft, but is unlikely to do so in a major way at this point), actually predates the B-2A Spirit as we know it. It closely resembles Northrop’s original proposal configuration for the Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) program, which gave birth to the B-2A. Specifically, it lacks the saw-tooth trailing edge of the B-2 and appears optimized for high-altitude, highly efficient flight, and a very low radar signature from all aspects.

Back in the early-to-mid 1980s, uncertain of how effective stealth would be and fearful of emerging Soviet air defense capabilities, the USAF made a big requirement change mid-development for its ATB program. The service hedged its stealth gamble by demanding that its future stealth bomber have low-altitude penetration capabilities. This resulted in major changes to both Lockheed’s and Northrop’s design, the latter of which was nicknamed Senior Ice. The result was the sawtooth trailing edge, among other tweaks, we see on the B-2 today. Gone was a deep, simplified v-shaped empennage. This increased the aircraft’s radar signature, especially from certain aspects, and resulted in a drop in its operational ceiling and overall efficiency.

In hindsight, and as a result of world geopolitical events, this proved to be an unnecessary decision that added billions to the program and decreased the B-2’s potential. You can read more about the ATB competition and Senior Ice’s Lockheed Skunk Works competitor in this feature of ours.

Fast forward to today and it appears that Northrop Grumman has leveraged that original concept to make good on the promise of its original ATB configuration, and then some. It’s easy to conclude that the B-21 should be a high-flying and super-efficient aircraft. And these attributes are very important.

Aim High

A higher operational ceiling means a better line-of-sight for sensors and communications systems, which means enhanced situational awareness and broader connectivity over a larger area. Both factors greatly increase the aircraft’s survivability, but they also allow the B-21 to become a more effective key enabler for other platforms and a critical player in the sprawling ‘kill web’ combat communications and sensor architectures of the future. This could include sharing sensor data and potentially working as a networking node and data-fusion gateway for other stealthy platforms operating forward and sharing that info not just locally within line-of-sight, but around the globe beyond line-of-sight to key decision makers.

We have no idea exactly how much of this capability will be available early on in the B-21’s career, but we know that open architecture and future upgradability is a massive element of the B-21 design philosophy.

“The B-21 is multi-functional,” U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said at the rollout event in December last year. “It can handle anything from gathering intel to battle management.”

Operating higher up also makes it harder for marauding fighters or airborne early warning aircraft to ‘paint’ the upper side of the aircraft with radar. This also means greater survivability. Beyond that, it means more efficiency, which translates into a longer unrefueled combat radius. This is absolutely critical, too, as the B-21 will need to weave its way unrefueled through an enemy’s anti-access/area-denial defenses that can range out thousands of miles from a target area. By most indications, the B-21’s range will likely be startling when it is officially disclosed.

“Let’s talk about the B-21’s range. No other long-range bomber can match its efficiency,” Secretary of Defense Austin also said during the rollout. “It won’t need to be based in-theater. It won’t need logistical support to hold any target at risk.”

In addition, serving in many other roles beyond striking fixed targets, the B-21 will have to loiter for long periods, potentially deep inside contested territory, as well. Every bit of efficiency helps, and a higher ceiling can help in that regard.

It will be very interesting to see what the Air Force says about the B-21’s ceiling as time goes on.

So yes, in terms of its basic configuration, it would seem that the B-21 is a ‘B-2 2.0,’ or even an early ‘Senior Ice 2.0,’ of sorts, but for all the right reasons.

Second Chances

Beyond these general elements, winning the Long-Range Strike Bomber (LRS-B) contract that resulted in the B-21 Raider gave Northrop Grumman the chance to take every lesson it has learned pioneering stealth bomber technology, both the good and the bad, and distill it into a brand new design. We cannot understate how big of a deal this is. The B-2 was so cutting edge at the time it emerged in the late-1980s and so few were built that they are almost experimental aircraft to this day and they have been painstakingly improved upon ever since.

Raider is literally the product of all of the blood, sweat, and tears that went into making and then sustaining the B-2. From a certain point of view, you can think of the B-2’s operational career as a three-decades-long, very expensive, but arguably successful, experiment of sorts. There are other more recent advanced programs that have also fed directly into its design, like the X-47B for instance, and surely others that remain classified. So, in this case, pedigree is not intangible. It is the bedrock of the B-21’s value proposition and Northrop Grumman has a ton to live up to and deliver on in this regard.

With the maker of the B-2 helming the LRS-B project, by its very nature, the resulting B-21 was bound to be obtusely evolutionary, as well as revolutionary.

Vanishing Act

At the same time as being similar to the B-2, the B-21’s configuration is also remarkably different. It shows decades of advances in stealth technology, turbocharged by advanced computer modeling, and huge advances in composite construction and material sciences. The deeply buried inlets alone — structures that are critical to the aircraft’s stealthy signature and basic operation — are stunning and clearly a challenge to pull off. We actually have officially disclosed proof of this fact.

The reality is that Northrop has pioneered major advances in low-observable inlet design going back to Tacit Blue, the great grandfather of the B-21, and continued making these advancements with the YF-23, which you can read all about here.

The inlet and exhaust design on any low-observable aircraft are among the most challenging and critical features to develop. Based on the limited images we have, the fact that Northrop Grumman has been able to bury the B-21’s inlet to the degree we see them in the upper fuselage, overcoming the boundary layer air issues associated with such designs, is an achievement. Deeply buried engines fed by serpentine ducts and very low observable exhausts with the kitchen sink of infrared suppression know-how thrown at them are also certainly part of the B-21 concept. The B-21’s inlets are just a good example of how much more advanced the low-observable shaping is on the Raider compared to anything that has been disclosed before it, especially the B-2.

The B-21’s next-generation radar-evading stealth is meant to be very hard to spot and engage at relevant distances not just primarily from fire control radars, but other radars as well, including those operating at longer wavelengths. Sometimes this is referred to as ‘broadband’ stealth. The almost organic, flowing, seamless, seashell-like nature of its mold-line underscores just how minimized any radar ‘hot spots’ are, especially from the critical frontal aspect, but radar returns are likely far better attenuated from nearly every angle compared to its predecessor. In fact, we know this to be true just based on its simplified trailing edge and overall planform, as discussed earlier.

Still, shaping is just one ‘facet’ of stealth technology. For instance, the F-117 relied 70% on shaping and 30% on radar-absorbent material (RAM) to achieve its low-observable RF (radio frequency) signature. The RAM that will coat the B-21 — the composition of which would be one of the country’s most closely guarded technological secrets — will no doubt play a big role in its ability to survive in highly contested territory.

It’s also what lies beneath the Raider’s skin that matters. Heavy use of composite structures minimizes radar reflectivity and radar wave-defeating structures buried under its skin to deaden the returns of certain bands would likely play a role, as well. This practice goes all the way back to the dawn of stealth in the form of the A-12 Oxcart.

In other words, some of the B-21’s most advanced stealth features are likely more than skin deep.

Even the B-21’s intriguing windscreen and side windows are a very big departure from the Raider’s forebearer. Yes, they look comparatively tiny and clearly they were the result of a careful balance between signature requirements and visibility considerations. It’s likely Raider pilots won’t need to look outside much based on current technology — even back during the ATB program the absolutely necessity of a windscreen was supposedly debated — but being able to see out to your wings and especially looking up for aerial refueling is still important enough to include a windscreen and side windows. Still, these really do look heavily influenced by signature demands, especially from lower viewing aspects. The bottom line is that there is very little about the windscreen configuration that harkens back to the B-2.

Of course, minimizing the B-21’s infrared (IR) signature, not just from its exhausts but from its airframe, as well, is more critical than ever in an age of advanced infrared search and track systems proliferating around the globe. The ability of heavily networked integrated air defense systems to blend various sensor capabilities together to create a single weapons engagement-quality track is precisely the challenge the Raider was designed to confront. The B-21’s airframe is likely cooled, using circulating fuel as a heat sink is one known practice, but its exhaust system would be among its most advanced and sensitive features.

Once again, we are talking ‘broadband’ stealth here — a new level of low-observable technology — both in terms of RF and IR. The magician’s book of tricks here is vast and largely unspoken. We will likely never live to fully comprehend all the features Northrop Grumman has deployed to make their new bomber as guileful as possible, with much of the magic being buried under the jet’s almost organic-looking outer shell. The same can probably be said even for the decades-old B-2, for that matter.

There is also the subject of the B-21’s current color tone — it’s light not dark. This could very well indicate that special attention is being put on daytime operations, not just nighttime ones like its predecessor, which wears a much darker motif. This would fit with the B-21’s much broader mission set, as well, which would likely demand daytime operations over, or at least very near, highly contested territory. The lighter shade we see could also change once the aircraft’s advanced RAM coating is fully applied, but it seems to be more of a conscious choice, even at this stage, than just a byproduct of the manufacturing process.

The fact is that no aircraft is undetectable, but detecting a puzzling signature for a fleeting moment from a specific angle is not the same as being able to track and engage that target over any significant amount of time. Even signature ‘hotpots’ can be used to one’s tactical advantage. In the end, survivability is gained through a cocktail of measures and countermeasures. Making the B-21’s radio frequency emissions from its sensors and communications systems as undetectable as possible, advanced electronic warfare capabilities, absolutely game-changing levels of situational awareness, careful route planning, and the ability to adapt on fly leveraging that awareness, as well as employing new weaponry to fight into and out of a target area, are all probable aspects that would meld together into a lethal and survivable next-generation bomber concept like the B-21.

And even the B-21 won’t fight alone. The full spectrum of terrestrial and space-based capabilities, including remote ones like cyber attacks on air defense nodes launched from around the globe, would help it succeed in any future fight.

But maybe the B-21’s greatest trick of all won’t be the ability to hide from advanced networks of enemy sensors; it will be just existing as an affordable — relatively speaking — stealth bomber.

Surviving The Budget Battlefield

The Long-Range Strike Bomber (LRS-B), the initiative that gave birth to the B-21 Raider, came on the heels of the canceled Next Generation Bomber (NGB). Without going into another story in itself (we can save that for a future article), remember that the NGB was a very high-end ‘and the kitchen sink’ bomber initiative. It came to an end, in part, on the grounds that it would be too complex and expensive, and would be at great risk of suffering the same budgetary ‘death spiral’ fate as the B-2 Spirit that resulted in a tiny fleet of hugely expensive bombers.

The NGB initiative occurred during a time of two deepening and hugely expensive counter-insurgency wars. Stealth bombers were not at the top of the DoD’s must-have list at this time. Competing priorities, like buying mine-resistant vehicles for deployed troops, eclipsed the need for a new ‘gold-plated’ stealth bomber. Also, Russia and China hadn’t exploded into the threats they pose today. As a result, the LRS-B program that followed the NGB was a far more rationalized affair. It would leverage an emerging leap in digital design and seemed to focus on a very low observable airframe mated with some mature, or at least semi-mature, technologies and sub-systems. This was done to mitigate risk, accelerate development, and keep costs down. The structure of the program was also designed based on lessons learned from the B-2 procurement debacle, which included smart procurement tactics that focused on keeping bureaucratic meddling and mission creep at a minimum. This has proven, in retrospect, all critically important to the success of the B-21 so far.

Nowhere is the rationalization of the requirements more apparent than in the B-21’s size. Slightly smaller than its predecessor — we estimate the B-21 is very roughly between 135 and 155 feet wide, while the B-2 is 172 feet wide. One thing to remember is that wingspan is just one metric. The internal volume of the Raider is likely larger than it looks based on its ‘bulged’ belly profile and the fact that it has a much larger v-shaped trailing edge compared to the B-2’s truncated sawtooth one. This will result in more depth and additional internal volume. Regardless, clearly it came down to what size bomber would be needed to maximize what is really necessary and minimize what really isn’t. Payload was clearly one of these tradeoffs.

More Brain, Less Brawn

The B-2 can carry somewhere approaching 70,000 pounds of weapons in two bays, including two 33,000-pound GBU-57/B Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) bunker busters. The B-21 will not be able to carry two of these weapons according to pretty much all speculation. Its weapons payload is likely around half that of the B-2’s, and that is a very good and logical thing.

Keep in mind that the B-2 was developed before the fire-and-forget GPS/INS-guided smart bomb revolution that gave us weapons like the Joint Direct Attack Munitions and eventually Small Diameter Bombs. It was primarily built to deliver dumb bombs and nuclear gravity bombs, but the first GPS-enabled weapons (the GBU-36/B GPS Aid Munition, or GAM) were rushed into operation specifically for the B-2. The massive potential for pairing these types of weapons with a long-range stealth bomber was glaring from the beginning. You can read all about GAM and the B-2 in this recent historical feature of ours.

Even in the early part of the B-2’s operational career, its raw weapons payload figure was not critically important. In a new emerging era of advanced fire-and-forget all-weather smart bombs, it was about the capabilities of the weapon more than the raw number of them available to be released. Instead of hitting one large target or two on a conventional strike sortie using dumb bombs, with GPS-guided weaponry, dozens of targets can be hit with extreme reliability on a single sortie.

The B-2’s nuclear mission didn’t require such a payload in the post-Cold War-era, either. Today, with the newly-acquired high-accuracy of the vastly updated B61-12 nuclear bomb, this is especially true, not to mention a new very long-range stealthy nuclear-tipped cruise missile that is also on the way.

As far as GBU-57 MOPs — which is still a niche, but very important weapon — just having two B-21 deliver two MOPs is a far better concept of operations than sacking the airframe with having to be able to deliver two at a time. The B-21’s design — and the Air Force’s budget — would have to ‘pay for’ that requirement for its entire service life even though it would only be most beneficial for one specific aspect of the aircraft’s mission set, which will be far more diverse for the B-21 than the B-2. Even then, the Raider would still deliver MOP, just likely one at a time instead of two. With the focus seemingly being on making absolutely sure that many more Raiders end up being produced and enter the fleet than Spirits, limiting its payload and thus increasing its chances of production success via lower costs and risk, this becomes even less of a factor. The idea is that there will be plenty of B-21s to put whatever bomb load needs to be on a given target regardless of the individual aircraft’s smaller weapons payload.

So, assuming the B-21’s weapons payload requirement was cut roughly in half over the B-2, you can see how many design possibilities open up. Could we get away with two engines instead of four (still unclear what the situation is there)? Could we deliver a very impressive fuel fraction, not just by cutting back on weapons capacity but also by leveraging next-generation large composite structures and increasingly miniaturized sub-systems and sensors to pack as much gas in the airframe as possible? Less airframe should also mean less cost to procure and sustain, so how can we optimize a smaller bomber? How much more likely will a smaller design be when it comes to surviving development and making it into mass production? Clearly these questions, and many, many more, were ones Northrop Grumman’s team asked itself and the answer was the B-21 Raider. You end up with a smaller and more affordable, deep-penetrating aircraft, that can still bring a lot of weapons to bear on a single mission and do so over vast distances. And those weapons are just getting smarter.

When it comes to raw numbers, if the B-21 can carry let’s say 35,000 pounds of weapons, and is equipped with new smart racks that can accommodate many smaller weapons, like the GBU-53/B StormBreaker, in mass alone that would equate to up to 140 bombs. Each of these weapons is capable of flying 50 miles to their individual targets (likely farther if the B-21’s ceiling is markedly higher). Of course, internal volume and weapons rack configuration limitations could dictate a bit smaller payload of weapons like the GBU-53/B, but the destructive capabilities a single B-21, let alone a fleet of over a hundred of them, could bring to the table on one mission, without putting refueling or support assets in danger, is fascinating to imagine.

Numbers really matter just in terms of payload and cost, too. Would you rather have double the bombers with half the payload or half the bombers with double the payload? Beyond simple economies of scale in terms of production and sustainment, and in an age of smart weapons where huge payloads just aren’t necessary, that answer is straightforward. Fulfilling high numbers of sorties with a larger pool of more reliable, but smaller bombers and doing many more things than just traditional bomber tasks on those sorties also results in an overwhelming verdict to this question.

Acquisition Cost Is Just The Cover Charge

Specifically designing a B-21 that could be produced in significant numbers at a comparatively reasonable cost with a good value proposition has to be the critical design driver, above all else. If anyone suffers from the budgetary trauma of production cuts and ballooning aircraft costs, it’s Northrop Grumman. As mentioned earlier, the B-2’s procurement saga remains a cautionary tale of mammoth proportions within the company and in many other defense firms, not to mention the Pentagon, for that matter. It seems absolutely clear that Northrop Grumman and the Air Force would do anything possible not to relive the B-2’s fate, especially considering how critical acquiring a new bomber has become, and the LRS-B’s scaled-back requirements seem to have given them a perfect opportunity to do just that.

The price of the plane itself is just one part of the focus on cost. In terms of metaphor, I always say, with aircraft, and especially when it comes to military aircraft, the development cost is the price to get to the nightclub. Usually that isn’t cheap. Think limousine transportation. The acquisition cost is the cover charge to get inside the club. It’s a one-time fee that isn’t cheap, but it usually gets the most adverse attention. The bottle service/drinks once you are actually in the club, well, that is the sustainment cost over the life of the aircraft. A long night of partying can drain your bank account far worse than the price of admission and getting to the front door. This is true when it comes to keeping an aircraft flying, but especially with an absolutely top-of-the-line thoroughbred combat aircraft. The thing is, sustainment costs are more complex to understand and harder to explain than development and acquisition costs, so they usually don’t get the same attention. But for the Air Force, they are a gargantuan concern.

By every indication, the B-21 features a design and coatings that will make it much more reliable and serviceable than the B-2. According to the USAF’s own admission, it can be parked outside year-round under a canopy and it is meant to be a flyer, not a temperamental hangar queen. It is essential that Northrop Grumman shatter the stigma that stealth bombers equal a very costly, small ‘silver bullet’ force, not just in terms of readiness, but especially when it comes to the cost of operations and sustainment over the long haul.

The B-2A is the most expensive weapons-carrying aircraft the Pentagon flies, by a big margin. They are massively labor intensive, even after major advances in the durability of their RAM coatings and in the techniques for applying them, as well as other improvements to the aircraft’s systems. So we know reliability and serviceability were critical design drivers for Northrop Grumman’s LRS-B offering.

A smaller and more developmentally mature aircraft will help in this regard. Just how mature the B-21 really is remains unknown publicly, but Northrop Grumman has made a special point to make it clear that its prized aircraft is far more mature than what we would historically think it would be prior to its first flight. The use of digital design for development and extensive testing in the virtual space was a major help in making good on this claim, according to the company. But as we already discussed, we know that the LRS-B program would focus on infusing many mature, or at least semi-mature, technologies and components into a very low-observable airframe. As such, we may even see direct commonalities with other aircraft in terms of components and even some software. One could wonder if a version of the F-35’s avionics and software, or even just aspects of it, could have ended up in the B-21, for instance. These measures could massively help with keeping the operating and upgrade costs of the aircraft down over decades of use. Open architecture systems and potentially a modular approach to some of its components could make the bomber even more user-friendly and future-proof.

It really comes down to the fact that you can have the best combat aircraft ever conceived with the biggest payload, but if you only end up with a handful of them, their impact on the battlespace will be very limited. This is especially magnified in a peer-state conflict that spans huge swathes of the globe.

Quantity Has A Quality All Of Its Own

When facing an enemy like China in the Pacific Theater, the B-21 is really shaping up to become an essential tool. It seems some have discounted this reality without understanding the nature of the tactical challenges that must be overcome. We are talking about target sets in the many tens of thousands here, and that is still a limited conflict. You need significant combat mass that can deliver direct, penetrating strikes on targets night in and night out, not just during the opening of a conflict, although that is essential too. There will never be enough standoff weaponry to overcome these numbers, nor can those weapons achieve the same results in many scenarios.

In some cases, such as deep bunker busting, there is no standoff weapon short of a nuclear strike to do what a B-21 will be able to do with MOP. The B-21 will have to deliver direct strikes in contested airspace, including hitting many geographically displaced targets on a single mission, if need be. We are talking about a different capacity here than the B-2. You cannot take on this challenge with 20 highly finicky bombers, of which a little over half are even usable at any given time. You need large numbers, and they need to be reliable so that their availability doesn’t crumble early on in the conflict.

On the tactical side, fighters do not have the combat radius (measured in hundreds of miles) or payload to make anywhere near such an impact and they could have very little impact at all if their tankers are threatened far from their targets and their runways are cratered.

The U.S. has over-invested in short-range tactical airpower. It’s just a glaring and inconvenient reality. The B-21 could help offset that mistake.

Not Really A Bomber

Another way the B-21 isn’t like the B-2 is that it will likely execute — or will be capable of accommodating — a multitude of missions, such as potentially working as the aforementioned networking node for other platforms operating deep inside contested territory. It could find itself overseeing swarms of diverse unmanned combat air vehicles and working as a forward battle manager for other stealthy assets. Working as a penetrating intelligence-gathering platform in its own right is also a given. Its weapons will be far more diverse than its predecessor’s, too. Electronic warfare-enabled air-launched decoys, defensive and supportive air-to-air capabilities, anti-radiation and extended-range quick-reaction missiles, drone-like air-to-air missile carriers, hypersonic cruise and advanced anti-ship missiles, and more, could find their ways into its weapons bays. Laser weapons or even possibly active protection systems could one day help it defend itself.

Even smaller weapons, like relatively simple air-launched drones capable of flying to their own targets or working individually as kinetic weapons, sensors, decoys, or stand-in jammers in a cooperative swarm could theoretically see a B-21, acting as an anti-access-busting delivery platform, deploy throngs of munitions on a single sortie. You could even see these drones create their own wide-area mesh sensing network, with the B-21 working a central node and relay for whatever important intelligence the swarm detects. Once again, the miniaturization of highly-capable smart weaponry, and especially the cooperative networking of at least some of them, opens up all new possibilities when we think of a ‘stealth bomber.’

Finally, at least based on our understanding, the B-21 is still to be at least capable of being adapted for unmanned operations in the future. This is certainly a new idea for a long-range nuclear bomber. Whether this capability materializes operationally or not will have to be seen.

All this flexibility speaks to another critical part of the Long-Range Strike initiative, of which the B-21 is the centerpiece.

A Family Of Systems Alongside Another Family Of Systems

LRS, from its inception, was focused on developing a family of connected ‘Long-Range Strike’ systems, not just a new bomber. In fact, the program looked to distribute some capabilities of the failed Next Generation Bomber concept in order to reduce complexity, bring down the cost and development time, and increase flexibility and survivability not just of the bomber, but also of this new air combat ecosystem as a whole.

It isn’t clear how much of this original ‘distributed’ capabilities, ‘family of systems,’ LRS concept remains, especially as China rose in prominence as America’s primary pacing threat as LRS progressed. Maybe some of the capabilities stripped out of the NGB requirement for LRS-B initially were later restored as the program advanced. We simply have no idea. We do know that the LRS-B’s design was frozen years ago. We also know of one other part of the LRS program — the Long-Range Stand-Off (LRSO) missile. This is a very stealthy nuclear-armed cruise missile that will become America’s staple for standoff airborne nuclear strikes.

It is hard to imagine that at least some of the other components, if not all of the LRS family of systems concept, still exist. These could include high-flying stealthy surveillance and networking aircraft that can go where even the B-21 won’t and for extreme lengths of time. Penetrating electronic warfare aircraft and other systems were also mentioned as part of this concept early on, and could also make up this long-range penetrating ecosystem today. Basically, these assets could enable the B-21 to accomplish its mission or work individually if required. New sensors and networking capabilities are certainly a part of this ecosystem, too. We just don’t really know the status of any of these possibilities at this time.

It’s also possible that the original LRS program was stripped down to focus on the bomber and maybe a truncated number of other platforms, as we now see a very similar, if not even more ambitious initiative coming into play under the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program. The seeds of this program sprouted just as the B-21’s development was maturing.

NGAD is focused on the tactical side of the equation, developing a manned long-range, very stealthy manned tactical jet as its centerpiece, along with an ecosystem of unmanned collaborating platforms. New weapons, sensors, communications architecture, engine technology, and more, are all also part of NGAD.

Sound familiar?

Surely the B-21 will share in many of the fruits that eventually come out of NGAD, but just how much they are intertwined, or the exact relationship between LRS and NGAD remains undisclosed. One could imagine that the distance between them is next to nothing and that they are, in some cases, seamless initiatives, with NGAD building on and being tailored to, in some ways, LRS, and LRS dovetailing into and influencing NGAD’s emerging goals. These represent two adjacent layers of the same future air combat cake, if you will – one more tactical and one more strategic, with lots of overlap in the middle.

Once again, we just don’t know exactly how these two ambitious initiatives of different maturity are commingled at this time, but we should find out more as the Air Force opens up about what’s around the bend.

Raider Revolution

The bottom line is that the B-21 is part of something far greater than just itself and we don’t know what else is lurking in the shadows alongside it just outside our field of view. You can bet that there will be some big surprises in this regard in the years to come. And in this way, the B-21 is nothing like the B-2, which was largely envisioned as an ‘”à la carte’ stealth bomber.

So, yes, the B-21 clearly leans on the lessons learned from the B-2, apparently to even include leveraging elements of its original planform. So sure, in those ways the Raider is a ‘B-2 2.0,’ but it is far more than just that. It is a culmination of new technologies, existing ones, and new ways of thinking, not just in terms of acquisition and development, but also in terms of redefining what a bomber is, or at least could be. It’s also just a piece, albeit a huge one, both figuratively and physically, in not just one, but potentially two interwoven future air combat ecosystems.

With all that being said, a lot still has to go right before the B-21, and whatever else it’s being developed with, can be declared a success. There are bound to be major bumps in the road, regardless of the digital engineering and other new technologies and practices that are being applied to its cause. The Raider’s test flight program lies directly ahead and the development and fielding timelines surrounding this program are ambitious. So far, it seems like the B-21 is very much headed in the right direction, even in terms of cost, which is a remarkable achievement in itself.

Still, there is so much we don’t know about this aircraft or even the larger canvas it was painted on. It remains a ghost — one we got a dramatic glimpse of, but on its own terms. As a result, the fleeting Raider will likely haunt our dreams and the enemy’s nightmares for some time to come.

They don’t call it a stealth bomber for nothing.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com