The U.S. Air Force’s long-standing aspiration to increase the number of its squadrons to 386 by 2030 appears to have been dropped. The goal of an enlarged force, which was announced as long ago as 2018, is now deemed less important than fielding more capable platforms, with a particular eye on potential future conflicts with an increasingly advanced Chinese military. That, at least, is the view of the Air Force Secretary, the senior leader overseeing the Department of the Air Force, comprised of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force.

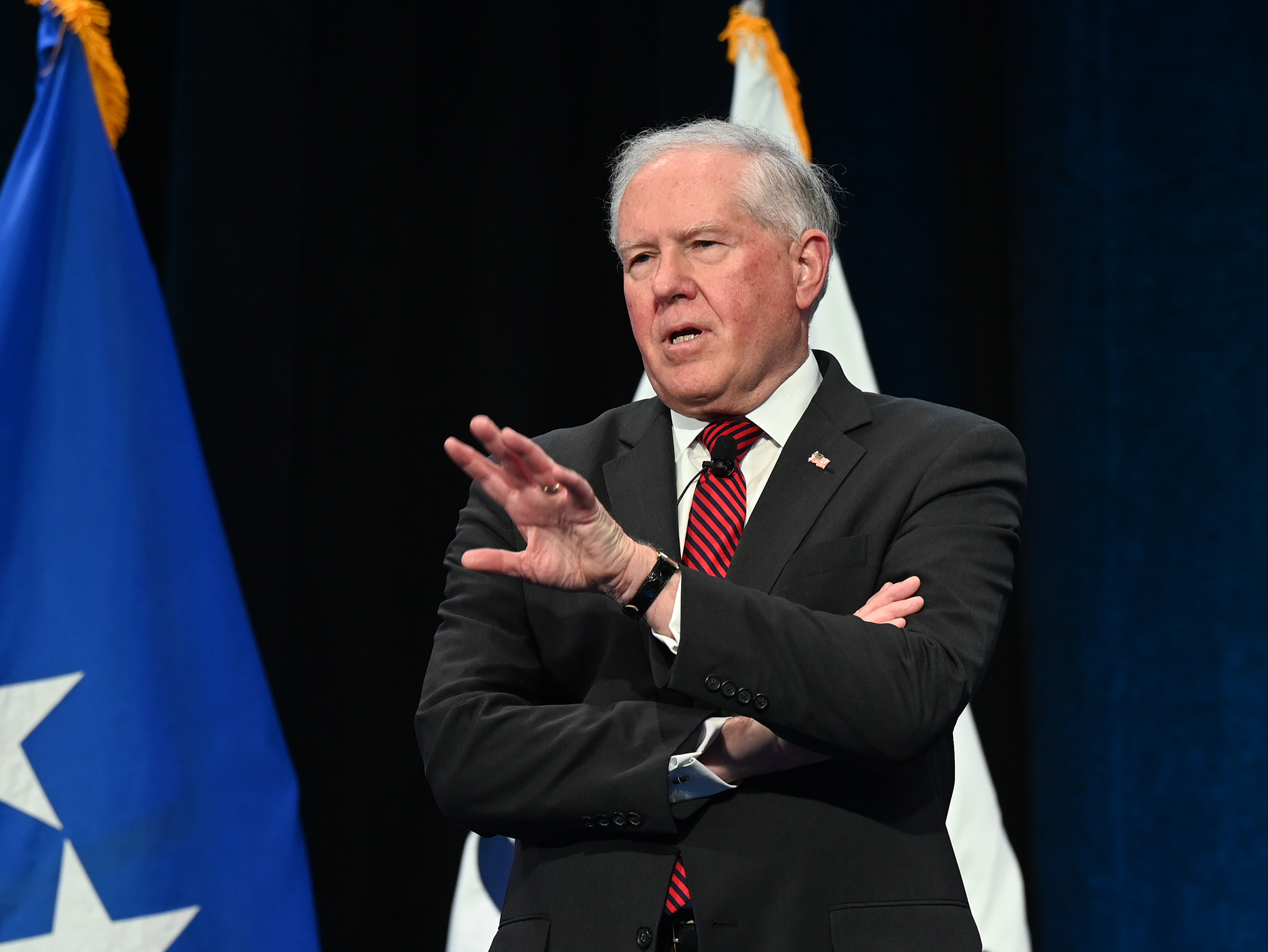

The development was announced by Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, speaking on a Brookings Institution webcast, under the title The future of American air power, on May 2nd, 2022. Among the highlights of a wide-ranging discussion were Kendall’s comments on Air Force size and structure and how these should be balanced, in the future, against capability levels which, in turn, will need to be optimized to meet the potential threat from the Chinese military.

“I’m not focused on counting end-strength or squadrons or airplanes,” Kendall said, but rather “I’m focused on the capability to carry out the operations we might have to support [toward] … defeating aggression. If you can’t deter or defeat the initial act of aggression, then you’re in a situation like we’re seeing in Ukraine: a protracted conflict.”

Of the war in Ukraine, Kendall said “nobody knows” how long Russia and Ukraine will “grind away at each other,” but “we don’t want to be in that mode.”

And while having more squadrons would support the kind of prolonged conflict that’s taking place in Ukraine, the kind of Air Force structure that Kendall is proposing would be tailored very much for the kind of threat posed by China, not Russia, and which would involve fighting “several thousand miles away” from many established bases against an opponent that combines high-end weapons with innovative ways of employing them.

“I am much, much more concerned about China than about Russia,” Kendall admitted, observing that at the beginning of his career, during the Cold War, the Soviet Union developed its armed forces by monitoring the United States and NATO and responding to the threat. Today’s China, on the other hand, exhibits much more independent thinking, developing its armed forces to reflect its own priorities — above all, displacing the United States as the preeminent global power.

The U.S. Air Force “really needs, first and foremost, to deter that act of aggression, and if necessary, defeat it, and so I am more focused on that than I am on quantity right now.”

To do that and dissuade — and potentially defeat — a fast-expanding and increasingly sophisticated Chinese military, the U.S. Air Force needs to focus less on its size and more on fielding more capable and modern assets.

“An awful lot of equipment that we have is old,” Kendall said, pointing out that the average age of one of the service’s aircraft is 30 years, and that this number is growing every year.

Playing a fundamental part in modernizing the Air Force will be the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program, or NGAD, one of Kendall’s key priorities, or operational imperatives. He described NGAD as a family of systems that will include not just a new manned platform, but also uncrewed combat aircraft, new weapons, connectivity architecture, and relationships to outside support.

While NGAD remains shrouded in secrecy, one thing that we can expect is an aircraft, or family of aircraft, that is able to fight more independently of refueling assets over much greater distances — something that would be required in a conflict with China.

Modernization will come in other forms as well, with Kendall highlighting the recent decision to buy the E-7 Wedgetail airborne early warning and control aircraft to replace a portion of the aging E-3 Sentry AWACS fleet. “I’d rather have that [E-7] platform, which also gives us a lot more capability, than the current fleet, even though the current fleet might be larger. So size isn’t important to me. It’s quality and getting as much quality into the force as I can as fast as I can.” Buying the Wedgetail should also help drive down sustainment costs, meaning that precious funds can be invested elsewhere. It is hoped that space-based assets will also help fulfill some of the loss of nearly half the E-3 fleet in the immediate future. The Wedgetail will takes years to field, leaving a real capability gap, at least without the existence of classified capabilities.

Kendall also reflected on another issue that’s of great importance in the Asia Pacific theater, the requirement for aircraft to operate without guaranteed access to traditional, established airbases. He identified “forward airfields, deception, hardening, and defense,” as some of the measures that the Air Force will need to increasingly embrace to make it harder for an adversary “to keep us on the ground or kill us on the ground.”

The Air Force Secretary also noted that while Taiwan has long been identified as the most likely flashpoint for a future conflict involving Beijing, there were other areas that could also see possible aggression and draw the Air Force into a wider conflict. In this context, he mentioned both the hotly disputed group of islands that the Japanese refer to as Senkaku and the Chinese refer to as Diaoyu, as well as the strategically vital and much-disputed South China Sea.

While Kendall was abundantly clear on his plan to discard the previous 386-squadron goal, it’s worth recalling that this was only ever a stated target and not a piece of policy with a corresponding budget assigned to it.

The number dates back to the tenure of Gen. David L. Goldfein, the previous Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, an assignment from which he stood down in 2020, to be replaced by Gen. Charles Q. Brown, Jr. When the then Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson expressed that vision, back in 2018, the Air Force had 312 squadrons, including Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve Command units. That total has not changed much at all since then.

Whether the case is being made for increasing the size of the Air Force or bolstering its high-end capabilities, there are inevitably budgetary challenges involved. With NGAD, as well as the B-21 Raider stealth bomber and nuclear modernization efforts all ongoing, there are some seriously expensive programs that all require funds. Development of the B-21 alone accounts for $381 million in the latest Air Force budget request, plus another $1.7 billion to actually begin purchasing the aircraft.

One way of helping reduce expenditure, Kendall says, is to reassess the way that the Air Forces goes about its research and development efforts. He expressly stated that he doesn’t want to see future technology demonstrations that don’t lead to “meaningful operational capability in the hands of operators as quickly as possible.”

This, again, could reflect part of the approach that’s already been taken with NGAD. While hard details of that program are scarce, we do know that it was born out of another one of Kendall’s initiatives, the Aerospace Innovation Initiative. This classified endeavor focused on test ‘x-planes’ that would be relevant to the future of air combat. Out of that, NGAD was born, and it yielded at least one demonstrator of some type that was already flying, even when the program was still supposedly in its conceptual stages. As it stands, we don’t know the nature of that demonstrator and even if it’s a traditional manned aircraft. Kendall says the NGAD program is now focused on locking in the final configuration of its central platform for eventual production, based in part on what was learned from the demonstrator.

Ultimately, the plan to skip traditional prototype test work and go straight into engineering and manufacturing development, or EMD, as Kendall proposes, could have its biggest benefits for future unmanned programs.

Then, once new platforms are in Air Force service, Kendall wants to see a more holistic approach to the upgrade of their various subsystems, with improvements to hardware and software being much better synchronized. This can include the Pentagon ‘owning’ the software and other elements of the design. This will allow it to compete any major upgrades without being tied to a single manufacturer for the lifetime of the aircraft.

The idea of rapidly fielding a new platform and then working to improve it incrementally once it enters the inventory is espoused by Kendall and it’s one that we’ve heard before. Broadly, it parallels the so-called ‘Digital Century Series’ approach that was the brainchild of Will Roper, the former Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics.

The Digital Century Series envisaged rapid development of new fighter jet designs, potentially at a rate of once every five years. While it isn’t clear if Kendall endorses that same vision, he has stated he wants to generally increase the pace of development drastically, talking of a period of just three years between a new capability being funded and the platform being declared operational.

While the idea of getting new hardware onto the flight line more quickly than before, and then continuously improving it, sounds attractive, it’s also one that’s potentially fraught with difficulties, as we have discussed before. Nevertheless, it seems that it’s not only already enshrined in NGAD, but will also be used in other programs, too. In the case of NGAD, it seems the Air Force may already be looking at fielding long- and shorter-range versions of the manned aircraft component, optimized for operations in the Indo-Pacific and European theaters, respectively.

The biggest concern that is likely to come from Kendall’s emerging strategy is near-term risk, by retiring far more operational aircraft than the already ‘too small for demand’ Air Force is buying, and especially the idea long-term that quality will far supersede quantity in the aerial battlefield of the future. No matter how capable a fighter or bomber may be, it can only be in one place at one time, and that is usually on the ground, with a substantial part of that time being torn apart for maintenance. In an expeditionary fight, where the U.S. is fighting thousands of miles from home, or even from secured airfields, quantity becomes a real issue in order to sustain the fight over the long haul. China will be fighting on its own turf without these strangling issues and its force is growing in both quantity and quality.

Compared to Russia, though, China is able to field new systems much more quickly once certain military requirements are identified. And since Beijing’s overall approach is far less predictable than previous potential adversaries, then the onus is on the Air Force to be able to adapt just as quickly to offset these threats.

On the positive side, in Kendall’s analysis, is the fact that China isn’t necessarily bringing new capabilities to the front line quicker than the United States can, but he did also note that in certain fields China does have a head start and also, thanks to its industrial potential, it’s able to work across multiple programs simultaneously.

It’s Kendall’s view that Beijing is taking the initiative in establishing a new world order in which it sits at the center, setting the rules for the economy. Whether this new reality will also involve military campaigns that seek to expand China’s territorial footprint, Kendall is less certain.

Despite that wariness, Kendall also warned that not taking Chinese assertions on its future position and influence would be a mistake. China has “articulated pretty clearly where they want to be my mid-century,” Kendall said. For the Air Force to be in a position to best dissuade future Chinese aggression, or to defeat it in a conflict scenario, bigger is no longer better, at least according to the Air Force Secretary’s latest assessment.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com