For years now, armed forces around the world have been adding hard-kill active protection systems to their tanks and other armored vehicles. These systems are primarily designed to physically destroy or at least disrupt incoming anti-tank guided missiles and other infantry anti-armor weapons, such as shoulder-fired rockets and rocket-propelled grenades. However, when it comes to defending against drones, especially highly maneuverable first-person view kamikaze types like those wreaking havoc on armor in Ukraine, these same systems could potentially be used to provide another highly valuable layer of protection.

Hard-kill active protection systems (APS) already come with a combination of sensors, effectors, and fire control components. Being able to adapt those APSs directly to the counter-drone role, including via software tweaks, hardware additions, and/or other modifications, would be a huge win. Not only would this provide a critical additional layer of defense against an ever-growing threat, and do so without the need for the installation of entirely new systems, but it could help save money by leveraging what’s already installed.

What are hard-kill active protection systems?

Though the development of hard-kill active protection systems (APS) dates back to the 1970s, they have only seen more widespread operational use in the past decade and a half. Israeli firms have been and continue to be pioneers in this field.

Multiple types of hard-kill APSs exist today, most use projectiles of some kind to physically disrupt or destroy incoming threats, the launch of which is cued by an array of sensors. Radar arrays and electro-optical and infrared cameras distributed around the vehicle are typically used by these systems.

Launchers preloaded with projectiles, including ones with explosive warheads or types designed to destroy/disrupt their targets by sheer force of impact, are the most common effectors. The Israeli-designed Trophy, which has been growing in popularity internationally, including with the U.S. Army, is a prime example of a hard-kill APS that uses projectiles (in this case kinetic ones) to repulse fast-moving threats.

Other hard-kill APSs systems use actively-triggered directional explosive charges, which function in a broadly similar manner to passive explosive reactive armor (ERA). Rheinmetall’s StrikeShield, the third generation of what was originally known simply as the Active Defence System (ADS), is one such APS design.

Regardless, these systems’ sensors and fire control computers can rapidly recognize an incoming threat, and in an instant, attempt to mitigate it. This all happens far faster than a human can react and is automated based on various modes that can be set during different combat circumstances. The result is something of an ‘invisible pseudo-shield’ that, while not by any means impenetrable, can reliably counter many threats that can pop up out of nowhere. Israeli APS capabilities are highly active today in the dense and at times ferocious fighting in Gaza, for instance.

The drone threat

Drones have been a demonstrable threat on and off the battlefield, and to nation-state military and security forces, for years now, as The War Zone routinely notes. ISIS terrorists in Iraq and Syria were already underscoring this reality with attacks involving weaponized commercial and homebuilt uncrewed aerial systems the better part of a decade ago now. All of this also highlights how low the barrier to entry can be, with many improvised armed drones having unit costs in the low thousands of dollars, at most.

Though hardly the only example of their use, the conflict in Ukraine has become a highly visible source of evidence for how effective even improvised weaponized drones, let alone purpose-built designs, can be against traditional military targets. Not a day goes by now without new video footage showing drones of various kinds in very active use by Ukrainian and Russian forces.

The situation has evolved into an uncrewed arms race, with both sides racing to significantly expand the production of different tiers of armed drones. Armed uncrewed aerial systems have come to steadily rival artillery, long a top killer in the ongoing fighting, in terms of priority of acquisition and battlefield impact.

For their part, Ukrainian authorities say they want to see the production of a million highly maneuverable weaponized first-person view (FPV) drones just this year, plus thousands of other loitering munitions and lower-end kinetic types. This may be an unattainable goal, but it shows how dire the procurement of these weapons has become. Ukraine held a significant advantage when it comes to FPV drones on the battlefield that has now eroded, with Russia taking the lead. Moscow has also made the production of these drones and other loitering munitions, such as the Lancet series, a top priority.

FPV drones with improvised warheads, which attack their targets by ramming into them and detonating, have been shown to be especially capable of destroying and damaging tanks and other armored vehicles. They have also proven to be extremely hard to defend against.

FPV drones can be used in significant volumes to increase the chances of seriously damaging or destroying their target. As the video from Ukraine in the social media post below shows, a single tank can easily find itself swarmed by armed uncrewed aerial systems while moving through a contested area.

Weaponized uncrewed aerial vehicles configured to release one or more munitions onto their targets have also become ubiquitous in the skies over Ukraine’s battlefield. The weapons these drones employ are often repurposed hand grenades or other kinds of ammunition. These uncrewed systems have shown that they can drop munitions with high degrees of accuracy and cause the catastrophic destruction of armored vehicles as a result.

There is a clear value proposition for the attacker in all this, too, with drones costing thousands of dollars being able to knock out tanks and other armored vehicles worth hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars. The cost ratio is still likely favorable even if the target is only removed from the fight for a period of time for repairs, which could be expensive if key systems, such as optics, are damaged or destroyed.

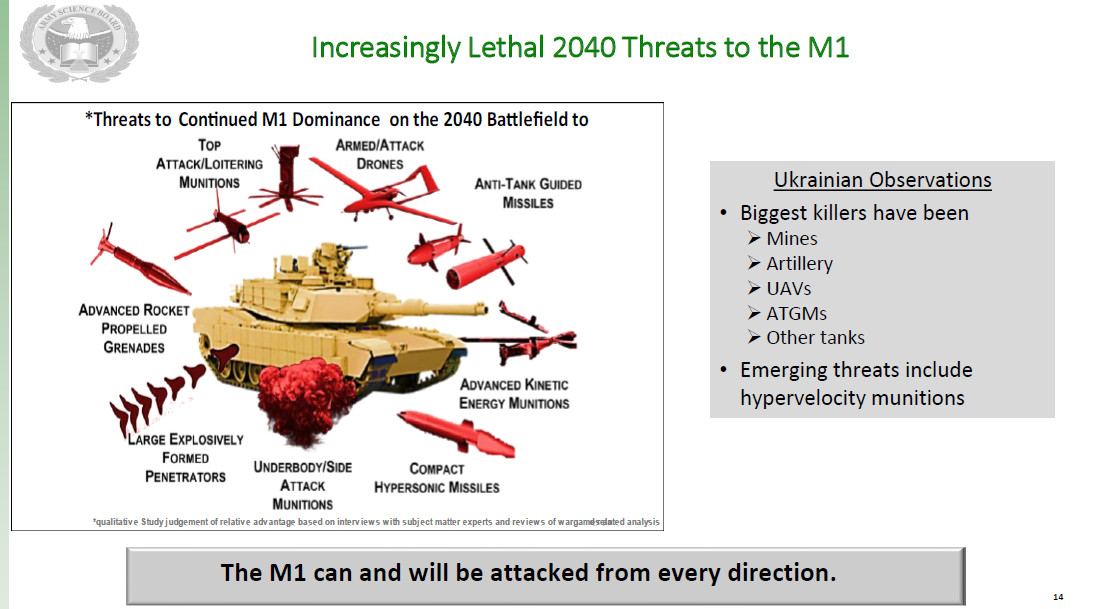

Lower-end uncrewed aerial threats to ground forces are only expected to grow in the future. Drones, together with “overwhelming artillery fires … ATGMs [anti-tank guided missiles] in top attack mode, and mines can and will degrade maneuver and potentially create the most deadly and dangerous battlefield we have ever faced,” a U.S. Army Science Board report on the future of armored warfare released earlier this year warned about the expected threat picture in the 2040s.

“I’ve been in the Army for 38 years, and in my entire time in the Army on battlefields in Iraq, in Afghanistan, Syria, I never had to look up,” now-retired U.S. Army Gen. Richard Clarke, then head of U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM), said at the annual Aspen Security Forum in 2022, underscoring the seriousness of the drone threat now. “I never had to look up because the U.S. always maintained air superiority and our forces were protected because we had air cover. But now with everything from quadcopters – they’re very small – up to very large unmanned aerial vehicles [UAV], we won’t always have that luxury.”

Hard-kill APSs as drone killers?

With many armed forces, including the U.S. military, still playing catch-up to the drone threat, trying to leverage hard-kill active protection systems that are already installed or are planned to be installed on armored vehicles makes great sense. In principle, the combinations of sensors and effectors found on currently fielded hard-kill APSs, especially those that use some type of projectile to engage threats, should offer at least some inherent capability for defeating certain types of uncrewed aerial systems, namely suicide drones and those dropping bomblets from above.

Manufacturers are taking notice already of how readily adaptable hard-kill APSs might be for tackling uncrewed aerial threats. Israel’s Elbit Systems says its Iron Fist system “can detect a drone or a loitering munition at around 1.5 km range” and has “successfully engaged drones simulating loitering munitions attack profiles” in testing, according to a story last year from EDR Online.

Iron Fist is a hard-kill APS that uses small active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars as its primary sensors to spot incoming threats and then uses projectiles with explosive warheads fired from small turreted launchers to knock them down. Passive infrared sensors are also an option for use with Iron Fist.

The War Zone has reached out to Elbit for more information about the Iron Fist’s counter-drone capabilities. We have also contacted several other manufacturers to get additional details on the ability of other existing APSs to neutralize uncrewed aerial systems and any work being done now on future capabilities in this regard.

It is also not surprising then that discussions are already beginning to emerge about whether these systems can be leveraged in the counter-drone role. In December, Amaël Kotlarski, an editor for Jane’s Infantry Weapons, shared several briefing slides on X, formerly Twitter, showing how NATO is looking at the issue of using APSs to defeat drones from an interoperability perspective. The alliance currently has separate interoperability standards covering counter-drone capabilities and what are referred to as “defense aid suites (DAS) for land vehicles.” The slides explicitly pose the questions “is there a role for APS in the CUAS effort?” and “should drone-type based threats be included” in how the capabilities of DAS are assessed?

“We’re looking at different platforms, different technology,” U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Sean Gainey told Defense News in an interview last year in response to an explicit question about adapting existing capabilities, such as APSs, for use against uncrewed aerial systems. Gainey is head of the U.S. Department of Defense-wide Joint Counter-small Unmanned Aircraft Systems Office, or JCO, which is focused on coordinating efforts across the services to acquire different tiers of country-drone capabilities.

The threats that existing APSs were originally designed to defeat do present limitations for potential use in the counter-drone role. The very popular Israeli-made Trophy, hard-kill APS for instance, which you can read more about here, is known to be unable to engage targets directly above the vehicle on which it is installed. This is less of an issue when engaging infantry anti-armor munitions fired by personnel on the ground, typically at shallower trajectories. It would be a problem when trying to use the system to tackle uncrewed aerial threats. It may be possible to augment the system with sensors and effectors that cover the top hemisphere of the vehicle, as well as software tailored to this new threat class.

Palestinian terrorist group Hamas’ use of weaponized drones to target Israeli Merkava tanks with Trophy installed as part of their brazen attacks in southern Israel on October 7 brought the issue to the forefront.

Hard-kill APSs that use physical projectiles have the same issue of magazine depth when it comes to facing large numbers of drones as they do now when presented with a high volume of incoming anti-tank missiles or rockets. Lasers and high-power microwave (HPW) directed energy weapons have been presented as alternatives. However, lasers are also limited to engaging one target at a time, and both types have significant additional power and cooling demands over other hard-kill APS designs. Miniaturizing an HPW system in the APS role for a vehicle like a tank is another issue altogether.

It’s worth noting that the projectiles that hard-kill systems like Trophy and Iron Fist fire can also be a hazard to friendly dismounted personnel nearby. Care has to be given to put the system in the proper mode based on the threats present and the disposition of infantry nearby.

There is the aforementioned questions about what modifications APSs, which are geared toward spotting and engaging targets that are moving much faster than typical small drones, would be needed to be able to adequately detect and engage certain uncrewed aerial systems. For example, FPV types move faster than types that drop small munitions onto their targets, and those free-falling bomblets are likely what the APS would engage. It may be relatively easy to change the sensor parameters and produce models for the system to recognize incoming drone threats and engage them when able. Additional hardware would likely be needed for full coverage on some systems, but that is a far more attractive solution than adding an entirely new system onto the vehicle, which would come at great cost, installation hurdles, and bulk — something armor definitely tries to avoid if at all possible.

Layering defenses against drones and other threats on armored vehicles

Beyond using them directly in the counter-drone role, APSs of different types could be readily available starting places for adding these capabilities onto tanks and other armored vehicles in combination with other systems. A common open-architecture control interface that various systems can be plugged into would help support this kind of arrangement. The U.S. Army had at least been working on just like this in the past as part of a program called Modular Active Protection Systems (MAPS), with Lockheed Martin as the prime contractor.

One immediate option could be blending together hard-kill APSs with so-called soft-kill types, a combination that some defense contractors are already offering. Soft-kill APSs use non-kinetic effectors to disrupt the functioning of seekers, radio control links, or other components on incoming munitions. Effectors that work in this way include electronic warfare jammers, active infrared countermeasures, and directed energy weapons, such as laser dazzlers, that are not necessarily designed to cause permanent damage to a target.

Weaponized commercial drone drones, in particular, rely heavily on line-of-sight control links that could be jammed and onboard cameras that could be blinded. There are already growing reports that Russian forces in Ukraine have been increasingly employing vehicle-mounted electronic warfare systems, including ones originally designed to prevent the remote triggering of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), as additional layers of defense against drones. Counter-drone jammers of various types, including man-portable types and ones adapted from other counter-IED systems, have already been in increasingly widespread use in Ukraine and elsewhere around the world in recent years.

There are other examples of how hard-kill APSs could be readily layered together with other capabilities, especially with something like MAPS. An APS’s sensor array might be used to cue an existing turreted remote weapon station (RWS) with a machine gun or automatic cannon with a high-angle field of fire shooting programmable burst ammunition to engage incoming uncrewed aerial threats.

Gun-armed remotely-operated turrets, as well as small active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars, are already an increasingly common component of dedicated counter-drone and short-range air defense systems. RWSs have been growing in popularity just because of the basic benefits they offer in terms of providing additional firepower that personnel can employ from the safety of the inside of a vehicle, as well.

Blending counter-drone and other defensive capabilities makes good sense for tanks and armored vehicles in terms of operational flexibility. Not needing a different self-protection system to defend against each type of threat also helps reduce costs, both in installation and maintenance. This limits the additional weight and power-generation burdens a single vehicle has to contend with, as well.

More than anything, any one system wouldn’t be a silver bullet against drones, let alone a myriad of dangers armored vehicles already face on the battlefield today. Different systems that complement each other or help fill in gaps in coverage will be essential for maximizing survival.

“No one system is going to be able to defeat all these threats,” U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Gainey, the JCO head, also said at the Association of the U.S. Army’s main annual conference in October 2023. “If somebody has that system, come see me. I’m looking to talk to you, and we have some money that we’ll be ready to invest in.”

Altogether, it remains to be seen how APSs will factor into the growing counter-drone discussion in the future. However, these systems are already seeing growing use, and adapting them to deal with additional threats, if possible, isn’t just logical, in the case of the growing drone threat, it may be absolutely crucial.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com