The U.S. Air Force is looking to finally make real progress on acquiring a new aerial target drone that can act as a surrogate for stealthy fifth and near-fifth generation fighter jets operated by potential adversaries, such as China’s J-20 and Russia’s Su-57. This comes as the service appears to be moving toward winding up purchases of QF-16 Viper Full Scale Aerial Target (FSAT) drones, which are converted from retired F-16 fighters, with one of two conversion lines recently shutting down entirely.

The Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC) at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio posted a request for information (RFI) regarding a supersonic-capable Next Generation Aerial Target (NGAT) online on July 28. AFLCMC then issued a revised version of the RFI on August 19, based on responses to questions from prospective contractors. An aerial target drone, like the proposed NGAT, is typically used for the testing and evaluation of air-to-air and surface-to-air missiles, countermeasures, radars, and other sensors, as well as simulating various aerial threats during regular training and larger exercises.

“Numerous and varied threats throughout the world, plus tighter defense budgets, drive the need for new and innovative solutions towards providing the NGAT. The objective of this RFI is to determine the existence of sources that have the capability to design, integrate, build, test, manufacture, and deliver an affordable aerial target that is threat representative,” the August 19 version of the RFI explains. “The target should be capable of providing adequate fidelity presentations of advanced adversary threat aircraft (J-20, Su-57, etc.) for specific test scenarios.”

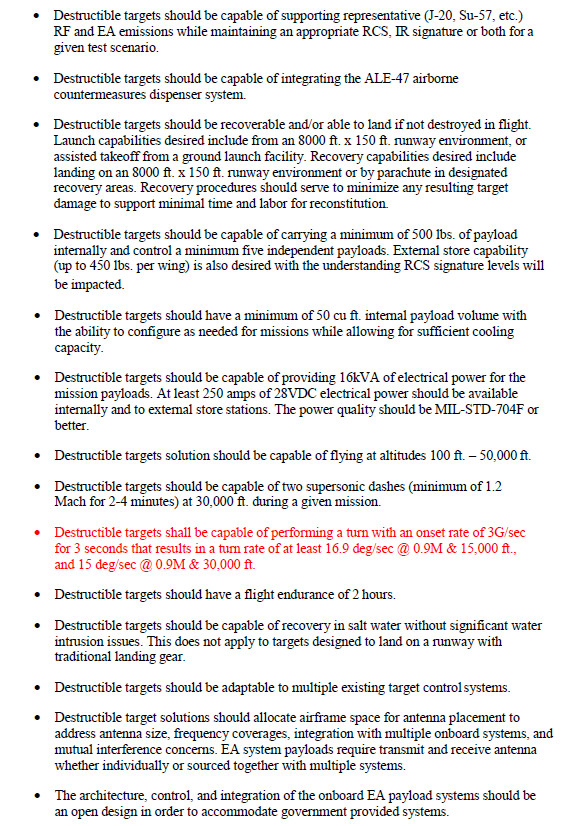

“The 5th generation representative target suite should be able to provide a remotely-controlled, destructible asset with threat representative RF [radio frequency] Emissions, EA [electronic attack] Emissions, Radar Cross Section (RCS) signature, Infrared (IR) signature, and internally carried expendables,” the RFI adds. “Remotely-controlled targets must be capable of autonomous operation, either under remote control by a human operator, autonomously by onboard computers, or any combination of the two methods.”

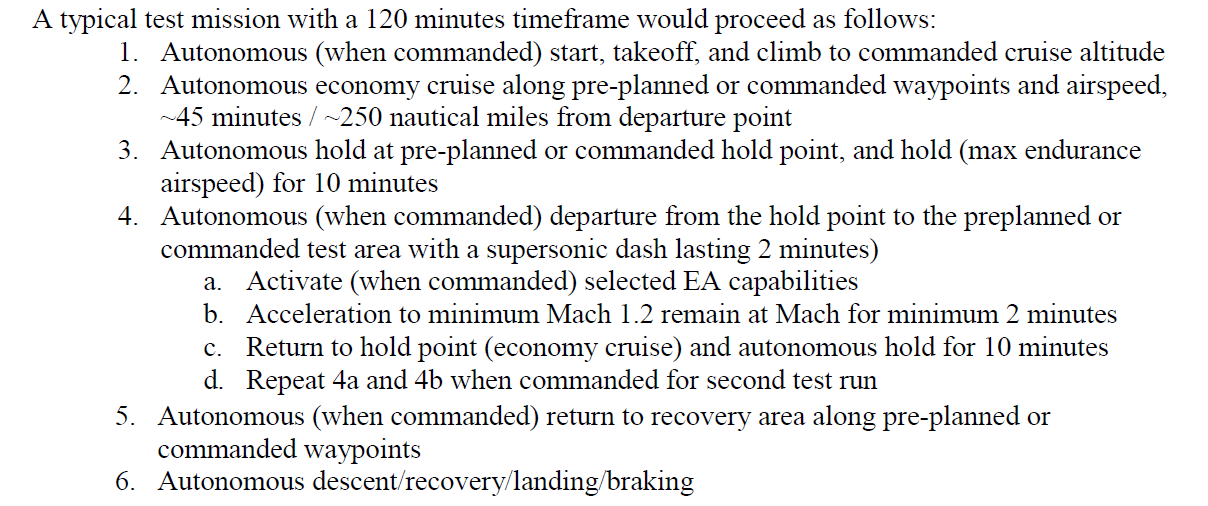

The RFI includes a description of a notional 120-minute-long mission that an NGAT should be able to perform, which is as follows:

The Air Force wants NGAT to be an expendable design, and cheap enough for that be an economical proposition, but also to be able to be recovered and reused if it is not destroyed in the course of a mission. The service says it has no preference about whether the drones are launched and/or recovered from a traditional runway or through other means, such as a rocket-assisted takeoff from a zero-length launcher and recovery by parachute. NGAT proposals can be either clean-sheet designs or conversions of existing types, as well, as long as they meet the other requirements.

Videos of QF-4 FSATs being used for AIM-9X trials:

Those other requirements include the need to be able to fly for up to 2 hours at a time at altitudes anywhere between 100 and 50,000 feet. The NGAT drone has to be able to conduct two supersonic dashes – flying at least Mach 1.2 at an altitude of at least 30,000 feet for between two and four minutes – in the course of one sortie.

“Destructible targets shall be capable of performing a turn with an onset rate of 3G/sec for 3 seconds that results in a turn rate of at least 16.9 deg/sec @ 0.9M & 15,000 ft., and 15 deg/sec @ 0.9M & 30,000 ft,” the RFI notes in terms of desired maneuverability.

In addition, the flying targets have to be able to carry an internal payload of up to 500 pounds, consisting of up to five different systems, and up to 450 pounds of stores under each wing. Those internal and external payloads may include “Electronic Warfare (EW) equipment, Radio Frequency (RF) emitters, Electronic Attack (EA) capabilities and expendables such as chaff and flares,” with the latter specifically having to be fired from a service-standard AN/ALE-47-series countermeasures dispenser.

The full list of desired “parameters” listed in the RFI is reproduced below:

The Air Force is looking for NGAT to be a highly modular design that will allow for the integration of new and improved capabilities and functionality as time goes on, as well.

“The NGAT solution is envisioned with flexibility and growth capability to adapt to new technologies for future threat representation, leverage technologies and design/manufacturing practices to give the vehicle the ability to grow with future technologies, and enable modifications to the system in order to keep up with emerging threats,” the RFI says. “The Air Force is interested in developing and demonstrating technologies that could enable highly affordable and capable vehicles.”

All of this needs to go inside a low-cost ‘attritable’ package. A broad definition of attributable unmanned aircraft typically described designs that feature a balance of capabilities and cost. In the context of target drones, this means unmanned aircraft that are suitably threat-representative, but are also cheap enough to be totally destroyed if the test or training scenarios demand it. The Air Force has historically had a relatively crude cost/capability matrix for determining attritability, often defining these designs as simply falling into a very large price range, from $2 million to $20 million. As The War Zone has explored in depth in the past, the service’s definitions of attritability have appeared to have been evolving significantly for some time now.

“Cost will more than likely be a determining factor,” but there is “no set cost bogie,” AFLCMC wrote in response to multiple questions on the NGAT RFI from prospective contractors. “[We are] looking for realistic cost data with [a] low cost attritable use case in mind.”

“[We have] no set number [of sorties before a shoot-down] defined,” another one of AFLCMC’s answers reads. “[We are] looking for designers to tell us how many flight hours the proposed airframe can withstand.”

As a comparison, the Air Force’s current QF-16s have a general lifespan of just around 300 flight hours in total. It has generally cost the service between $1 and $2 million over the years to convert a single F-16 into a QF-16. The QF-16 is optionally manned.

All told, at its core, NGAT makes good sense. The Air Force has made clear time and time again now that it needs more ways to represent fifth-generation threats, and more of them in general, to support exercises and other test and evaluation activities. With all this in mind, the service recently reactivated the 65th Aggressor Squadron at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. This unit is equipped with older block stealthy F-35A Joint Strike Fighters and is focused primarily on replicating the tactics, techniques, and procedures of Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) aviation units.

Within this broader context, demand for fifth-generation-representative aerial targets is likely to grow specifically for various reasons, especially to support the development of new air-to-air missiles like the AIM-260. The Air Force has already been using QF-16s to support the AIM-260 program.

Advances in digital engineering and modeling will help with all of this, too, but they will never entirely eliminate the need for full-up physical testing of weapons, as well as sensors and other systems, against advanced aerial threats.

Something like NGAT would also eliminate the capability and cost constraints imposed on designs that retain provisions for pilots for any reason, such as the converted QF-16s that the Air Force uses as full-scale fighter jet targets now. This, in turn, could enable these new advanced target drones to better simulate future enemy unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAV), as well.

However, it still remains to be seen whether or not the Air Force can make real progress on NGAT now. This is the third NGAT RFI to be issued in the last four years. The first one, put out in 2019, was effectively rendered moot by a lack of funding to pursue the project at the time. The second one was issued last year specifically to gain insight into any new relevant technologies that might have emerged in the meantime and to see how existing ones might have matured.

The Air Force did manage to start a formal NGAT project in the 2022 Fiscal Year, but received a paltry $99,000 in funding for it. The service’s latest budget request, for the 2023 Fiscal Year, is only asking for another $15,000 for this effort, specifically saying that “funding decreased due to continuing only limited concept planning activities.”

After the latest NGAT RFI was released in July, one prospective contractor asked AFLCMC about when an actual contract might be awarded. “The estimated award date is FY24 [Fiscal Year 2024], based on availability of funds,” was the response. The RFI does say that the Air Force “is interested in determining the feasibility of delivering 2-5 fully tested flying prototypes within 5 years of contract award,” whenever that might come.

There may now be additional emphasis on finally pushing ahead with NGAT given the scaling back of the QF-16 program. On July 29, Boeing’s conversion line at Cecil Airport in Jacksonville, Florida, delivered its last “Zombie Viper.” This facility had produced conversions for more than 75 QF-16s since 2013.

“A second QF-16 line, based at the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group in Tucson, will continue to operate through the remaining procurement contract,” the Air Force said in a release earlier this month, but it is unclear how many more Zombie Vipers are still to be produced. As of the 2021 Fiscal Year, the Air Force was set to acquire 134 of these full-scale targets in total, according to Air Force Magazine. Air Force budget documents do not show any requests for or appropriated funding for more of these converted F-16s since the 2020 Fiscal Year.

There is always the possibility that the service could still pursue additional QF-16 purchases in the future. However, stocks of older F-16s that are still viable for conversion into “Zombie Vipers” have steadily dwindled while the Air Force’s operational Viper fleets have only seen an increase in operational demands. Turning newer retired F-16s into drones may not necessarily be the best use of those aircraft, which would provide valuable sources of spare parts on short notice, or even entire airframes that could be returned to active service if needed.

No matter what, the QF-16s, which have relatively limited lifespans, are not representative of fifth-generation fighters. This can only limit their utility, especially at targets for use in the testing of new missiles, like the AIM-260, and other hardware. This, in turn, raises questions about whether this is a useful expenditure of funds and other resources, and shows that there remains a clear need now for a follow-on target that better reflects advanced threats that already exist.

The Air Force is not alone in this need, either. The U.S. Army has seen a surge in demand for additional and more capable ground-based air defenses in recent years, something that has grown further in light of what has been seen of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The service has also seen an obvious need to test those systems against more advanced threats, as well as just be able to train against them.

Unfortunately, the Army has been having difficulties in developing its own Fifth-Generation Aerial Target, or 5GAT. A prototype 5GAT drone built by Sierra Technical Services crashed on its maiden flight in 2020. The service initially moved to procure a second example of the Sierra Technical Services aircraft, but subsequently cancelled the project. In April, the Army issued its own new RFI for a 5GAT follow-on effort.

Sierra Technical Services’ 5GAT design has also been discussed as the possible basis for a semi-autonomous “loyal wingman” drone designed to work together with manned combat aircraft or even a lower-tier UCAV. This raises the additional possibility that the Air Force, as well as the Army, could seek to leverage work being done now on advanced attritable drones for other programs, such as the Skyborg project and its follow-ons.

The Air Force could similarly seek to secure additional funding for NGAT on the possibility that the resulting unmanned aircraft design could be adapted to other roles beyond acting as a target. Target drones evolving into operational types is something that has already happened on multiple occasions in the past. During the Vietnam War alone, the Air Force used a number of modified variants and derivatives of the Ryan Firebee target drone for intelligence-gathering, electronic warfare, and psychological warfare missions, among others. It tested additional versions as potential unmanned strike platforms.

More recently, drone maker Kratos’ transformed the BQM-167A target into the UTAP-22 Mako loyal wingman-type unmanned aircraft. UTAP-22s have been used to support the Skyborg program, among other projects.

Whatever might happen to the Air Force’s NGAT program now, the underlying requirements certainly aren’t going away. Whether this need is fulfilled as a result of whatever comes of this new RFI, prompted further by the winding down of the QF-16 program, or through a separate effort entirely, remains to be seen.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com