Air Force Special Operations Command wants to expand its ability to use beaches across the Pacific as impromptu airfields capable of supporting MC-130J Commando II special operations tanker/transports and other aircraft in future conflicts. This is part of a broader push to become more “runway agnostic” amid concerns about well-established bases becoming ever more vulnerable, especially in the opening phases of a potential high-end fight against a near-peer adversary like China.

Air Force Lt. Gen. Tony Bauernfeind, head of Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC), highlighted the importance of beach airstrips in future planning at a media roundtable that The War Zone and other outlets attended on the sidelines of Air & Space Force’s main annual conference the last week. Bauernfeind also shared additional details about other ways AFSOC is looking to reduce reliance on traditional runways, including continued interest in an amphibious C-130 Hercules variant and future high-speed vertical takeoff and landing-capable designs.

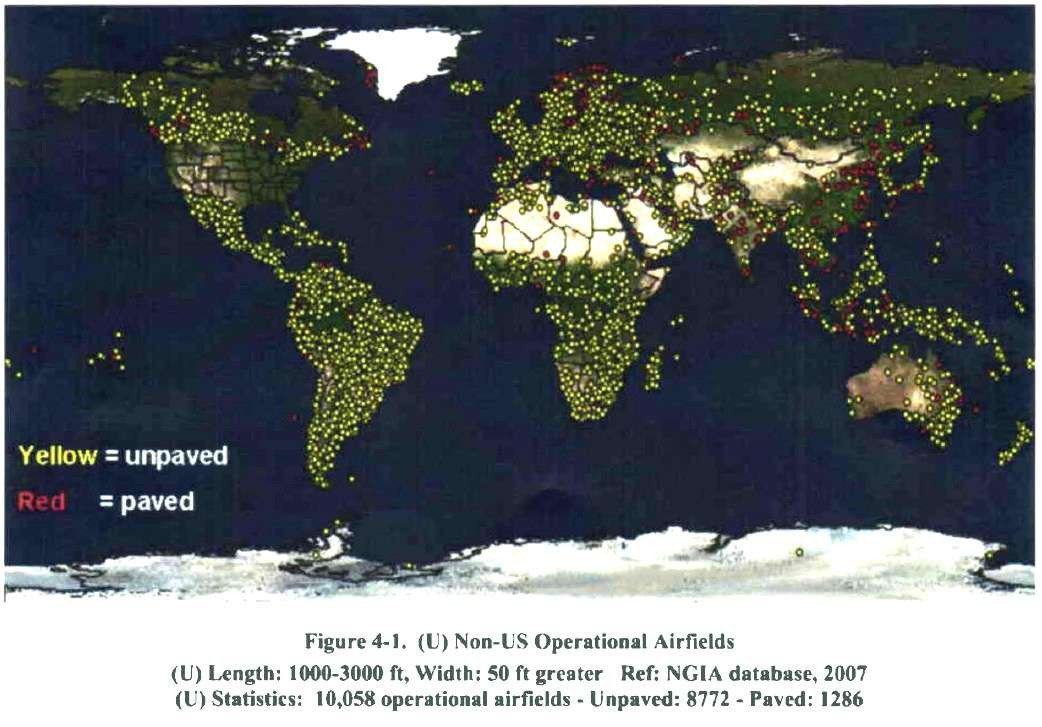

“We’re … looking at the ability for beach landings,” Bauernfeind said. “There’s a lot of 3,000-foot [long] straight beaches that we can bring MC-130s and CV-22s into to deliver the effects we need.”

AFSOC currently only operates one MC-130 variant, the MC-130J Commando II, which can be configured as a transport or an aerial refueling tanker. The C-130 family, as a whole, has long been renowned for its ability to take off from and land on a variety of unimproved surfaces, including dry lake beds and other dirt strips and runways carved out of ice.

The CV-22 is AFSOC’s special operations-optimized version of the V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor, which can take off and land vertically like a helicopter, but cruises similar to a traditional fixed-wing turboprop aircraft.

“Our adversaries have watched the American way of war for several decades, and they are going to hold our initial staging bases and our forward operating bases at risk. … They understand that [the way] to slow the American joint force down is … to target our basing,” Bauernfeind explained. “We have to acknowledge that we cannot always rely on a Bagram, a Kandahar, a Balad, [or] an Al Udeid in the future.”

The first two facilities Bauernfeind mentioned here were major U.S. bases in Afghanistan for years. Balad was an important American base in Iraq during the U.S.-led occupation of that country between 2003 and 2011. Al Udeid in Qatar remains a key hub for U.S. air operations in the Middle East and beyond.

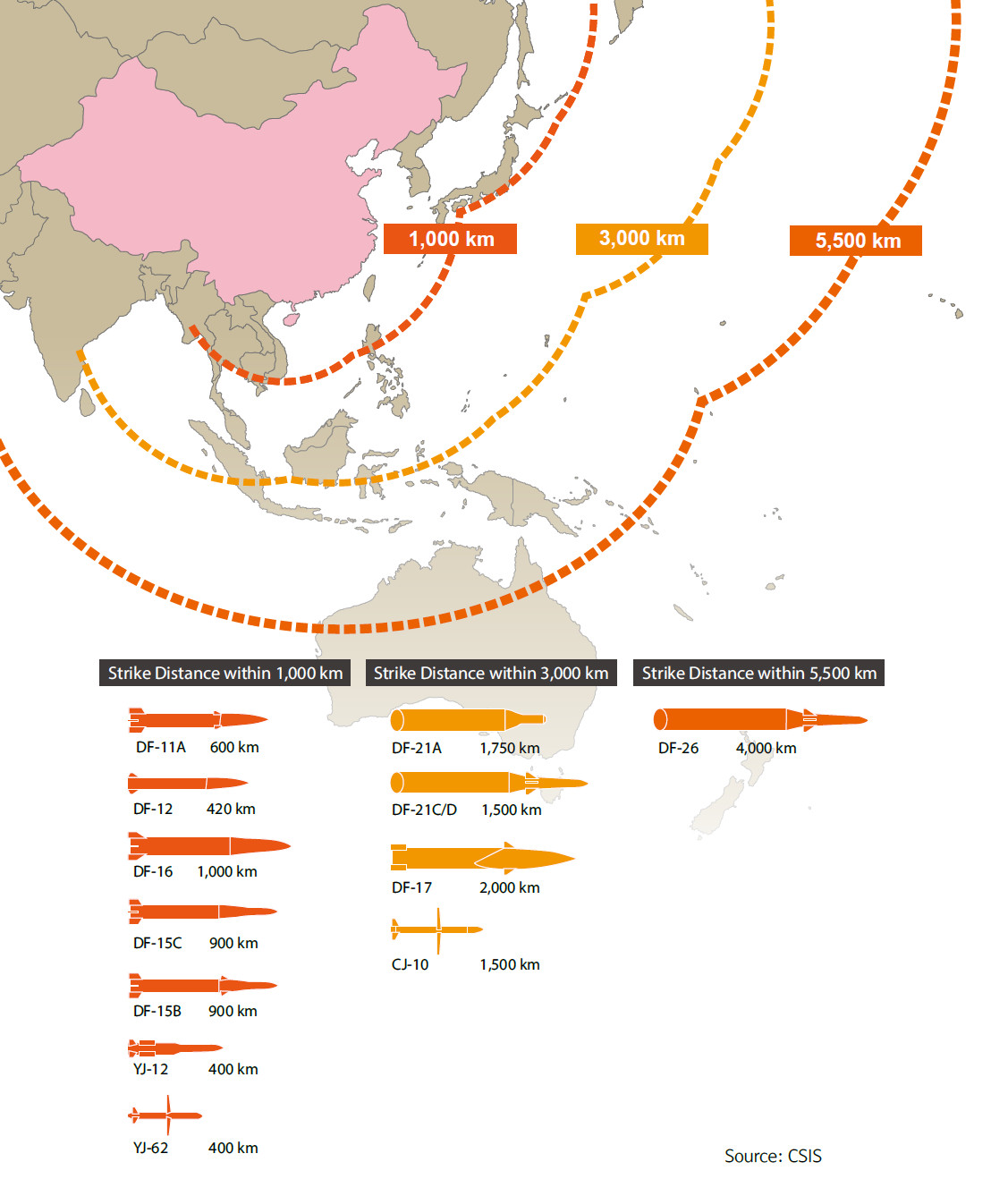

It is no secret that the entire Air Force is concerned about access to bases in any potential major fight in the future, especially one against China in the Pacific. China’s arsenal of long-range stand-off strike capabilities, including air, ground, and sea-launched ballistic and cruise missiles, only continues to grow.

For years now, already, the Air Force has been refining new distributed and expeditionary concepts of operations, collectively referred to currently as Agile Combat Employment (ACE), to help mitigate these vulnerabilities. ACE is heavily focused on the ability to rapidly deploy forces, and do so in less predictable ways, to a large number of facilities, including remote and austere locations. The service has also been exploring additional capabilities to complement these tactics, techniques, and procedures, including expanded fixed and deployable base defenses and new ways to deceive opponents.

Unfortunately, across much of the Pacific, access to dry land of any kind, suitable for use as a runway or not, can often be limited. The ability to make use of beaches as landing strips could be a valuable way to increase the total number of potential landing zones to support various types of operations.

It is important to note that the idea of using beaches as airfields is not new and dates back to World War II. The U.S. military also demonstrated its ability to rapidly construct air bases during the Korean and Vietnam Wars. The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps even built a land-based ‘aircraft carrier’ of sorts during the latter conflict, as you can read more about here.

The ability to establish more robust airstrips on many different types of surfaces using temporary aluminum matting remains a capability the U.S. military trains to employ. Portable arresting gear, akin to what is found on aircraft carriers, can also be put in place to allow higher-performance tactical jets to make use of those kinds of pop-up facilities, which often have relatively short runways.

However, what Bauernfeind was talking about last week was more in the vein of being prepared to operate from strips of beach without any kind of improvement. His mention of MC-130s in this context makes perfect sense as those aircraft can operate from a host of unimproved surfaces, to begin with, as already noted.

In fact, the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the United Kingdom and the Royal Danish Air Force routinely practice operating C-130-types from unimproved beaches in their respective countries. The RAF did retire the last of its C-130s earlier this year, but continues to conduct this kind of training using the A400M.

The head of AFSOC said last week that U.S. crews had taken part in similar beach landing training in Europe in the past.

“We have used beach landings in the past in the European theater. And so we’re going to work with our engineering teammates to understand if … the Pacific beaches” could be equally suitable for use as temporary airfields, Bauernfeind said. “We don’t know yet, but we’re gonna get the engineers looking at it.”

AFSOC is particularly well-positioned to explore the potential use of beaches in the Pacific as airstrips. Beyond its organic engineering community, which has years of experience establishing remote and austere facilities during the Global War on Terror era, its special tactics units regularly train to parachute in and set up temporary landing zones, often in denied areas. Declassified documents this author previously obtained via the Freedom of Information Act highlighted how so-called Assault Zone Reconnaissance Teams (AZRT) assessed nearly 300 sites just in the Middle East as potential landing zones, drop zones, or other temporary operating locations in 2013 in support of operations in the region.

This all requires well-established procedures to quickly assess the suitability of certain spots to handle various kinds of aircraft, which might be configured and/or loaded in unusual ways, and to be able to do at least some of that work remotely. Just in the past few years, AFSOC has demonstrated its ability to use sensors on MQ-9 Reapers to do aerial assessments of the terrain down below, including roads and dirt strips, to determine whether the drones can land. Historically, personnel on the ground have been required to do this work.

The video below shows an MQ-9, as well as an MC-130J and other aircraft, conducting road operations in Wyoming during an exercise earlier this year.

“We’ve recently been returning to tactics, techniques and procedures to find out where all of the 3,000-foot straight highways in the world are,” Bauernfeind also noted last week.

The Air Force has separately tested Litening multi-sensor pods, more typically used by combat jets for targeting and surveillance purposes, on C-130 cargo aircraft to help crews make precise airdrops and check that landing zones are clear of potential hazards. The service has also used podded radars mounted on C-130-type aircraft to conduct aerial surveys of ice runways in Antarctica to help ensure they are safe to use.

The same kinds of capabilities and skill sets will be applicable to determining whether or not beaches in the Pacific, or elsewhere, are suitable landing strips. Though AFSOC’s forces are particularly well-suited to conducting these kinds of operations, this is something that would be applicable to the rest of the U.S. military. Non-special operations Air Force units, as well as ones in the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, also fly C-130-types, for instance. The Marines have also been very actively experimenting with how they might operate F-35B Joint Strike Fighters, which can take off in short distances and land vertically, from locations without traditional runways.

Being prepared to conduct beach landings will be just one element of a larger set of future tactics, techniques, and procedures to help ensure friendly forces maintain their freedom of movement and protect them from enemy strikes, too. The entire U.S. military increasingly expects to have to conduct more distributed operations to reduce their vulnerabilities in future high-end conflicts.

AFSOC’s Bauernfeind made clear at last week’s roundtable that his command is focused broadly on “runway agnostic options,” which includes the MC-130J Amphibious Capability, or MAC, and the High-Speed Vertical Takeoff And Landing (HSVTOL) effort. The Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is also now running a project called Speed and Runway Independent Technologies (SPRINT), which the Air Force is involved with, as well.

The MAC “is still in engineering development, we’re still continuing to resource” it,” Bauernfeind said about that project. “It is a tough challenge.”

The War Zone has been closely following AFSOC’s renewed interest in an amphibious C-130 since the MAC project first emerged in 2021. In May, Air Force officials said that a flight test of a prototype configuration was still two to three years away, despite earlier hopes that it might have occurred sometime last year or this year. An amphibious C-130 would, of course, not need a runway on land of any kind, something that would also be of particular value in the Pacific.

When the HSVTOL or SPRINT projects might see actual demonstrators fly remains to be seen. Bell, which is working with the Air Force on the HSVTOL effort, did announce it had delivered a risk-reduction test rig, seen in the pictures below, for high-speed sled testing on the ground at Holloman Air Force in New Mexico earlier this month. You can learn more about Bell’s HSVTOL concept here.

HSTVOL could build upon important runway-independent capabilities that AFSOC has already gained from the introduction of the CV-22 back in 2006.

“We’ve had the CV-22 for coming up on two decades. And so we’re pivoting to the future of what will be replacing the CV-22 as we look at what is going to be that capability” going forward, Lt. Gen. Bauernfeind said last week. That is the “capability to have an asset that gets our special operations forces [to where they need to go] with a theater dash capability, but also that terminal area flexibility to land on a dime somewhere.”

AFSOC, and its predecessor organizations within the Air Force, have a much longer history of experimenting with various aircraft concepts to expand their ability to get in and out of often high-risk or otherwise sensitive locales. You find out more about these major projects in this past in-depth, two-part War Zone feature.

The command looks set to continue that extensive history with its current array of runway-agnostic efforts, which could also filter out in various ways to the rest of the U.S. military.

If nothing else, it seems very likely that we will see Air Force special operations units flying MC-130s and CV-22s, and possibly other aircraft, training more and more to make use of beaches around the world as short airstrips whenever necessary.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com