The U.S. Space Force’s top officer has provided an unusually detailed description of a vision for future counter-space capabilities and priorities in that regard — as well as the kinds of threats that the service faces. Chief of Space Operations Gen. Chance Saltzman’s comments came during the Air & Space Forces Association’s 2025 Warfare Symposium last week.

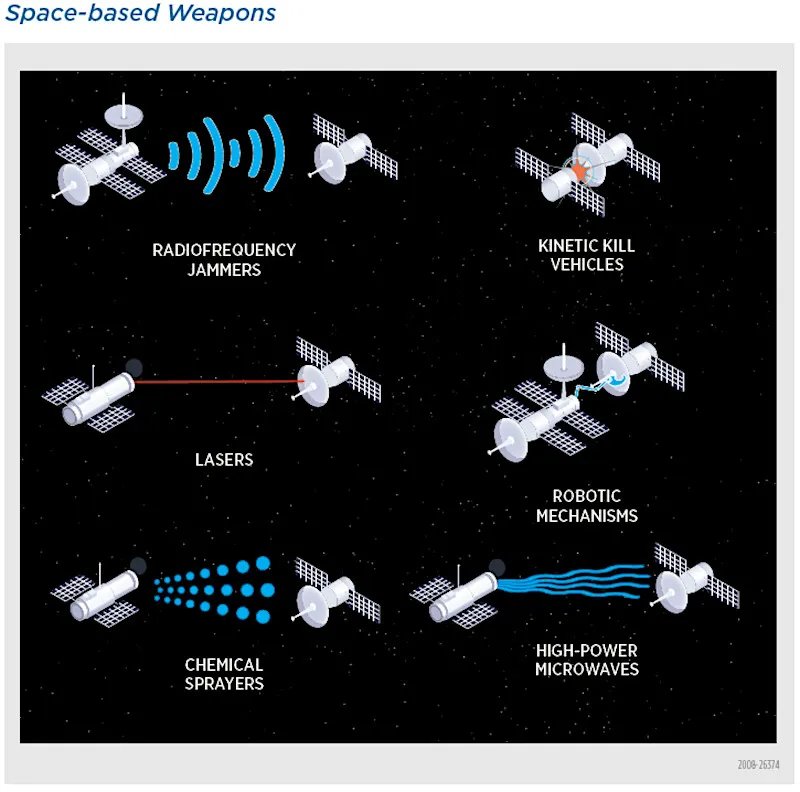

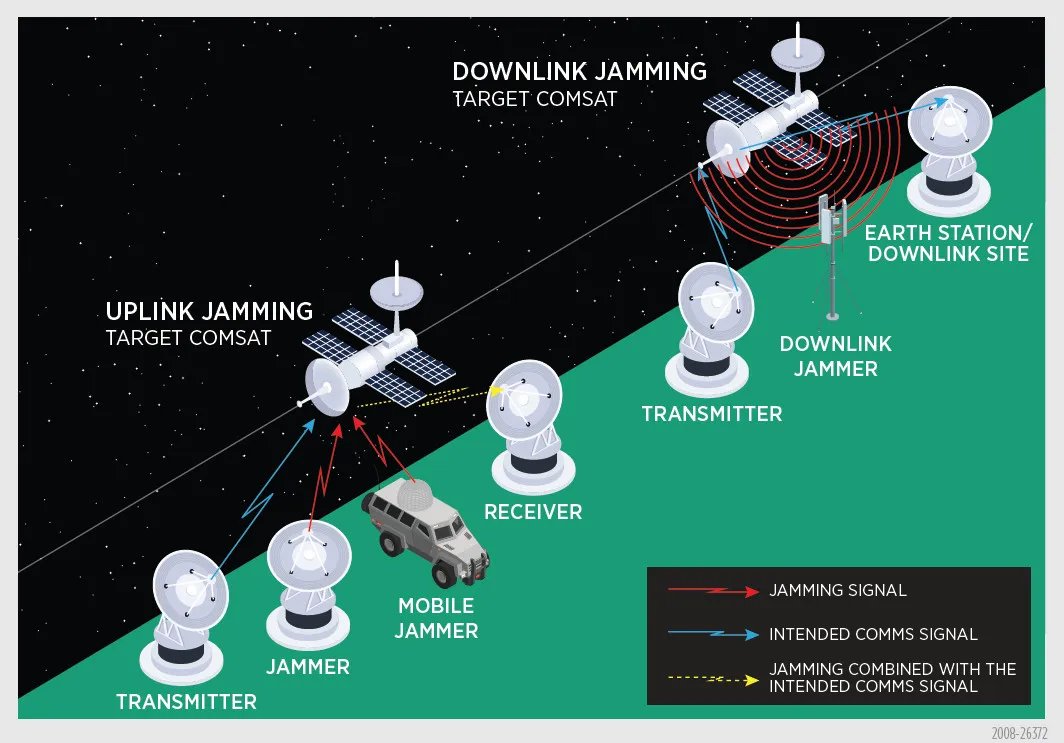

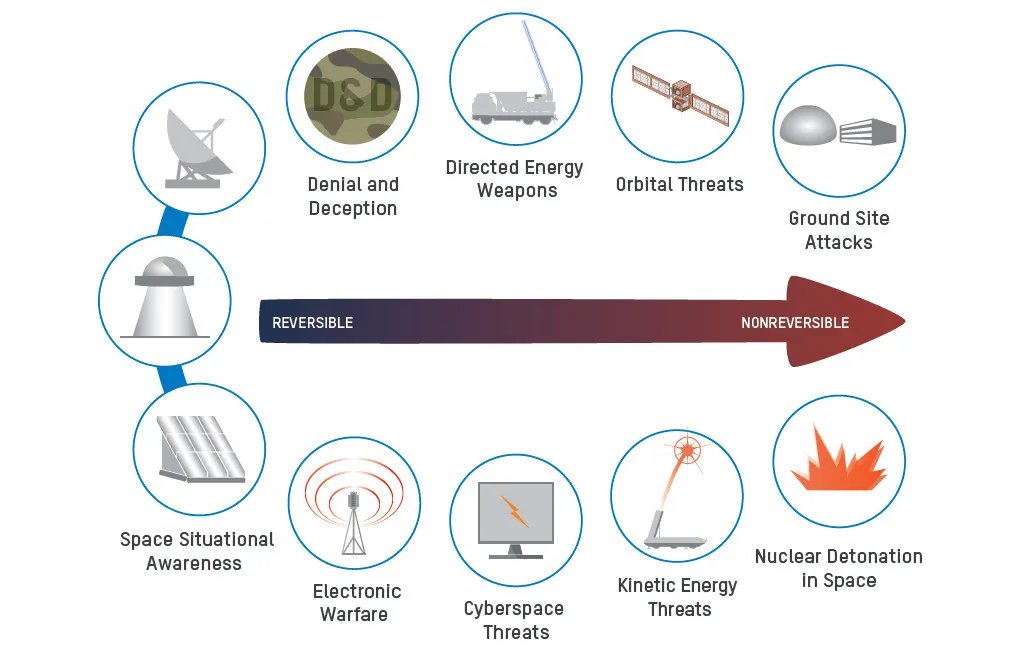

Saltzman began by categorizing the types of adversary weapons that the United States might expect to encounter in space. These are broken down into six broad categories, three that are space-based and three that are ground-based, but with the same threats in each set. In each of those domains, the three broad threats are directed-energy weapons, such as lasers, radio-frequency capabilities, including electronic warfare jamming, and kinetic threats, which attempt to destroy a target physically.

The latter category includes “killer satellites” positioned in orbit. As TWZ has explained in the past:

“A killer satellite able to maneuver close to its target could use various means to try to disable, damage, or even destroy it, such as jammers, directed energy weapons, robotic arms, chemical sprays, and small projectiles. It could even deliberately smash into the other satellite in a kinetic attack.”

“We’re seeing in our adversary developmental capabilities that they’re pursuing all of those,” Saltzman said.

As for the United States, “we’re not pursuing all of those yet,” Saltzman admitted, although he noted that there are “good reasons to have all those categories.”

A graphic from the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) provides methods that one satellite can use to attack another after it has been able to get in close proximity:

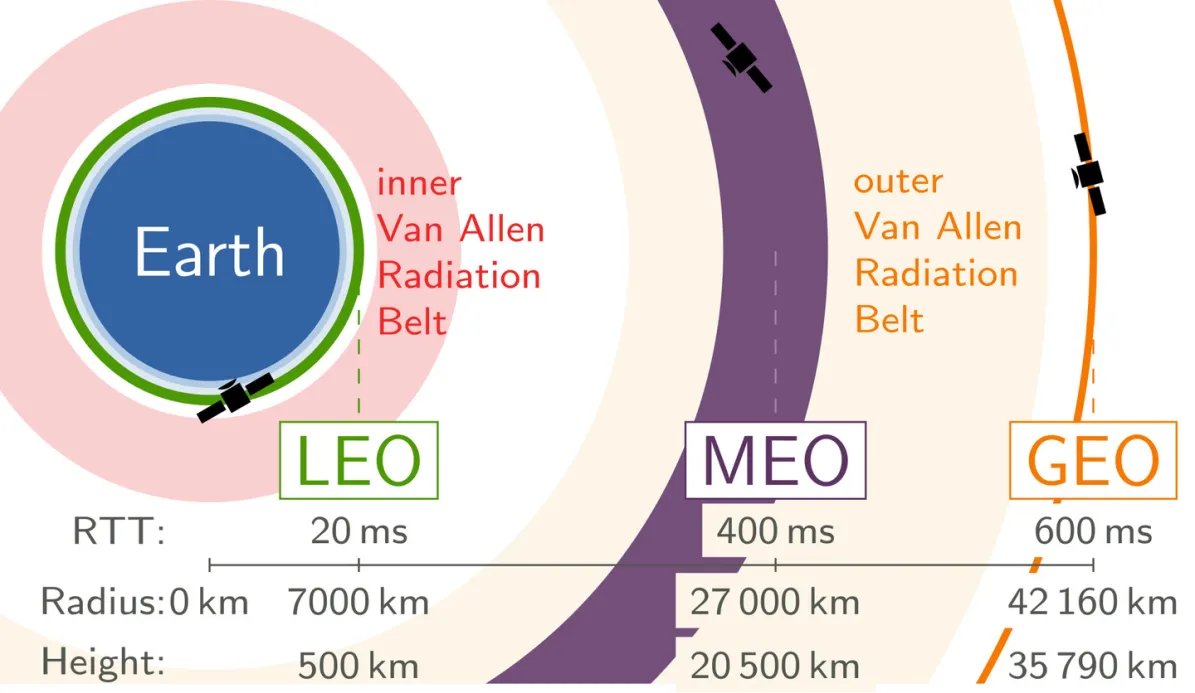

In particular, a broad range of capabilities is required to potentially counter a proliferation of satellites across low-Earth orbit, as well as in medium/high geo-synchronous orbit.

These different challenges, Saltzman observed, “require different kinds of capabilities. That which is effective in low-Earth orbit is less effective in GEO and vice versa.”

In terms of the kind of threats that the United States and its allies now have to deal with in space, Saltzman considers that the most concerning aspect “is the mix of weapons … they are pursuing the broadest mix of weapons, which means they’re going to hold a vast array of targets at risk.”

In this context, Saltzman identifies China as the most dangerous adversary, although Russia is also working on similar capabilities.

Back in 2021, Gen. David Thompson, at that time the Space Force’s second in command, pointed out that China and Russia were already launching “reversible attacks,” meaning ones that don’t permanently damage the satellites. These attacks include jamming, temporarily blinding optics with lasers, and cyber-attacks, and they target U.S. satellites “every single day.”

Thompson also disclosed that a small Russian satellite used to conduct an on-orbit anti-satellite weapon test back in 2019 had at one point approached so close to a U.S. satellite that there were fears an actual attack was imminent.

Even before then, U.S. satellites were coming under “reversible attack.”

In 2006, for example, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) confirmed that a U.S. spy satellite had been “illuminated” by a ground-based Chinese laser. On that occasion, it was a test with no impact on the satellite’s intelligence-gathering capabilities.

Since then, however, there has been an uptick in these kinds of attacks, underscoring the rapid development and fielding by Russia and China of a wide variety of anti-satellite capabilities.

As for non-reversible attacks, details in this regard are few and far between. In the past, when U.S. officials have been asked to confirm or deny whether any American satellites have actually been damaged in a Russian or Chinese attack, this information has been withheld as classified.

Nevertheless, with these various threats in mind, “the focus out of the gate has been on the resiliency of our architecture, to make the targeting as hard on the adversary as possible,” Saltzman said last week. “If you can disaggregate your missions from few satellites to many satellites, you change the targeting [requirements]. If you can make things maneuverable, it’s harder to target, and so that is an initial effort that we’ve invested heavily over the last few years to make us more resilient against those broad categories.”

As well as efforts to field “many satellites,” the U.S. military has been looking to develop and field new and improved space-based capabilities, as well as explore new concepts, such as distributed constellations of smaller satellites and ways to rapidly deploy new systems into orbit, to help reduce vulnerabilities to anti-satellite attacks, in general.

This kind of resilience is only becoming more critical as the United States and its allies increasingly rely on space-based assets for vital capabilities, including early warning, intelligence-gathering, navigation and weapon guidance, communications and data-sharing, to name just a few.

Of course, while Saltzman’s broad description of these six types of threats was framed around building resilience in space, the very same capabilities can be used, in turn, by the United States against its adversaries.

Typically, Space Force officials are extremely tight-lipped about these so-called “counter-space” capabilities.

“In the military setting, you don’t say, ‘Hey, here’s all the weapons and here’s how I’m going to use them, so get ready.’ That’s not to our advantage,” Saltzman said.

While unable to talk specifics, the Space Force’s top officer did approach the topic more generally.

“I am far more enamored by systems that deny, disrupt, and degrade,” he said, as opposed to ones that destroy. “I think there’s a lot of room to leverage systems focused on those D-words, if you will.”

Saltzman pointed out that although systems that ‘destroy’ come at a cost in terms of debris, “we may get pushed into a corner where we need to execute some of those options.”

Mainly, however, Saltzman’s Space Force is “really focused on the weapons that deny, disrupt, and degrade. Those can have tremendous mission impacts with far less degradation, in a way that could affect blue systems. That’s just one of the things about the space environment. I tell my air-breathing friends all the time, when you shoot an airplane down, it falls out of your domain.”

For the Space Force, using a weapon to destroy a target in space can lead to its own systems being threatened by debris. Saltzman pointed to the examples of the 2007 Chinese anti-satellite test and another by Russia in 2021 as “still causing problems” in terms of hazardous debris.

The 2021 Russian anti-satellite weapon test, in particular, involving a ground-launched interceptor, led to widespread condemnation, including from the U.S. government, and prompted renewed discussion about potential future conflicts in space.

The video below shows a past test of Russia’s A-235 Nudol, a ballistic missile interceptor with anti-satellite capabilities:

This is not the first time that a Space Force or Air Force senior officer has alluded to these kinds of capabilities, but such instances are vanishingly rare.

“There may come a point where we demonstrate some of our capabilities so that our adversaries understand they cannot deny us the use of space without consequence,” then-Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson said back in 2019.

“That capability needs to be one that’s understood by your adversary,” she added. “They need to know there are certain things we can do, at least at some broad level, and the final element of deterrence is uncertainty. How confident are they that they know everything we can do? Because there’s a risk calculation in the mind of an adversary.”

It’s worth noting, too, that the Biden administration vowed to halt U.S. destructive direct ascent anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons testing back in 2022, raising concerns about America’s ability to target enemy satellites, something you can read more about here.

In recent years, American officials have increasingly pointed to the policy and other problems caused by the extreme secrecy that surrounds U.S. military activities, as well as those conducted by the U.S. Intelligence Community, outside the Earth’s atmosphere.

Barbara Barrett, Wilson’s successor as Secretary of the Air Force, previously argued that “The lack of an understanding really does hurt us in doing things that we need to do in space.”

Meanwhile, the challenges the U.S. military and the rest of the U.S. government face in deterring hostile actors or actually responding to acts of aggression in space are by now fairly well established, although specific details remain scarce. Even more secretive are the kinds of capabilities that the United States is able to employ, in turn, to “deny, disrupt, and degrade” — and even destroy — the systems of its adversaries. While Saltzman wasn’t able to provide anything in the way of specifics, his comments may well reflect a growing openness to address these issues in the public arena.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com