South Korea’s ambitious plans to build its first aircraft carrier, known as CVX, appear to be under serious threat, with the news that the project has not been funded as part of the country’s proposed 2023 defense budget. That also raises questions about Seoul’s plans to operate F-35B stealth fighters but should be good news for its submarine fleet, which is earmarked to receive more funding, including for Dosan Ahn Changho class attack submarines capable of launching ballistic missiles.

Confirmation that the CVX is not to be funded in 2023 came yesterday from Naval News, which had already predicted that South Korea’s carrier program could lose out in the next defense budget.

The government defense budget proposal for 2023 was released on Tuesday and calls for a total of 57.1 trillion won, equivalent to around $42.5 billion, which is an increase of 4.6 percent compared to this year. The 2022 defense budget was set at 54.6 trillion won, roughly $40.6 billion.

Of the 2023 total, 17 trillion won (or around $12.7 billion) is allocated for new acquisition programs, an increase of two percent, with the remainder to be spent on the military’s day-to-day running costs, including wages and maintenance.

On Friday, the budget proposal will be submitted to the National Assembly for approval.

The CVX program is the highest-profile loser in the proposed budget and seems to be a victim of both changing priorities, in view of the North Korean nuclear threat, and perhaps also the increasingly ambitious scope of the carrier design itself. In particular, however, the new presidential administration under Yoon Suk Yeol is stressing significantly different policy positions compared with its predecessor, including a more hawkish approach toward North Korea.

Previously, South Korea’s LPX-II program envisaged an expanded amphibious assault ship design that would be able to accommodate short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) F-35B jets, much like the U.S. Navy’s own designs.

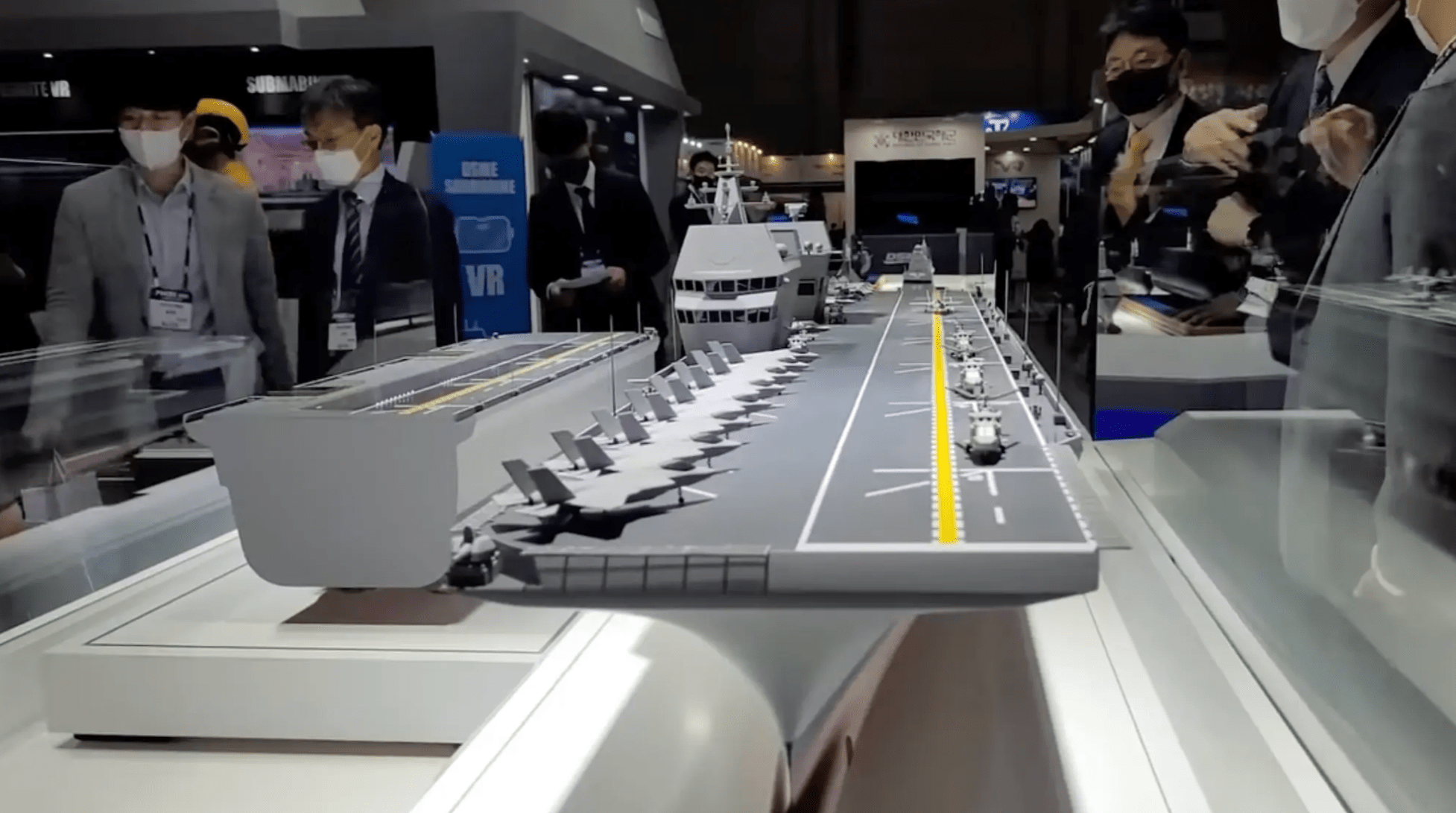

More recently, the CVX project yielded a design for a remarkably large aircraft carrier, including twin island superstructures and a ‘ski jump’ takeoff ramp, both features found on the U.K. Royal Navy’s Queen Elizabeth class.

That particular design, from Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), would have been 850 feet long, have a 200-foot-wide beam, have a fully loaded displacement of around 45,000 tons, and be able to operate up to approximately 20 F-35Bs.

Other notable features of the HHI design included an auxiliary deck area at the rear for operating small rotary-wing drones and an adapted well deck from which to deploy unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).

Another CVX proposal, from Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering (DSME), was somewhat more conventional, without the takeoff ramp on the bow but still with a dual-island superstructure. This warship would have been 860 feet long, 150 feet wide, and would have had a displacement of around 45,000 tons. It would have had the capacity for 16 F-35Bs and six medium helicopters simultaneously.

Both those CVX designs were considerably larger than the Republic of Korea Navy’s current Dokdo class landing platform helicopter (LPH), which is 652 feet long, 101 feet wide, and has a displacement of 19,500 tons.

While these two CVX designs were based around STOVL F-35Bs, there were even signs that Seoul might be considering an even larger and more capable carrier, perhaps even one outfitted with an angled deck, takeoff ramp, and arrester gear. This would have allowed short takeoff but arrested recovery (STOBAR) operations, perhaps by a navalized version of the KF-21 new-generation fighter, or larger types of drones.

Clearly, a carrier of any kind capable of fixed-wing aviation operations would have been a significant new development for South Korea — and also a colossal investment.

Each one of the Royal Navy’s Queen Elizabeth class carriers, for example, cost taxpayers around £2.3 billion, or roughly $2.85 billion, with annual operating costs running at around £96 million, or $112 million, without accounting for the air wing.

In the past, the new South Korean carrier was reported to have a likely price tag of around $1.83 billion, which seems highly optimistic, and the cost of the F-35Bs would have to be added to this well. The acquisition of 20 F-35Bs was expected to cost Seoul around $2.7 billion.

Previously, DSME officials had said a design contract for CVX could be awarded in 2022 and there was an expectation that South Korea could even have a carrier ready for service by the early 2030s.

This all now looks increasingly unlikely, with the future of the entire carrier project looking doubtful, although it’s possible South Korea could still find a use for F-35Bs, perhaps on its existing big-deck amphibious assault ships, although they would likely need extensive modifications. More realistic might be operating them from land bases. This would allow the jets to be dispersed for survivability, avoiding runways that would be vulnerable to North Korean missile strikes. Also, the ranges involved would suit the F-35B and South Korea would benefit from already operating the conventional takeoff and landing F-35A.

Aside from the sheer cost, it appears that the utility of an aircraft carrier is increasingly being questioned, especially as it relates to a potential conflict with the North. While undoubtedly being an impressive symbol of maritime power, and helping keep pace with China and Japan, a carrier doesn’t necessarily fit in with the so-called ‘three-axis system’ that’s increasingly being promoted as a central tenet of Seoul’s defense posture under the new administration.

The three-axis system is intended to develop a broader defense architecture that can better respond to a possible nuclear attack from North Korea. Firstly, there’s the kill chain element that’s intended to carry out a preemptive strike against Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile facilities to defend Seoul, if judged necessary. Secondly, the Korea Air and Missile Defense network is intended to destroy North Korean ballistic missiles targeting the South once they have been launched. Thirdly, there’s the Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation program, or KMPR, also known as Overwhelming Response, an effort to develop ways to retaliate against North Korea, using conventional weapons, should Pyongyang launch a first strike.

Seoul’s fast-developing submarine fleet would be expected to play a major role within KMPR, with the three-axis system slated to receive 5.3 trillion won or around $3.9 billion in funding overall, an increase of 9.4 percent over 2022’s figures.

After all, Seoul’s latest Dosan Ahn Changho class diesel-electric attack submarines, also known as the KSS-III, have been designed from the outset to provide the kind of survivable conventional strike capability that the KMPR plan calls for.

Of course, in a hypothetical conflict with North Korea, CVX could potentially also launch offensive missions from standoff range using its stealthy F-35s, although, as The War Zone has pointed out in the past, an aircraft carrier is otherwise not best suited to the kind of campaign that could be waged against the North.

Under the 2023 budget proposal, the KSS-III submarine program will receive 248.6 billion won or around $185 million.

The Dosan Ahn Changho class puts South Korea in a select group of countries that operate submarines with a submarine-launched ballistic missile, or SLBM, capability. Unusually for an SLBM, the South Korean weapon has a conventional warhead.

Successful underwater ejection tests of an SLBM from the first of these submarines were reportedly first conducted around September last year. That first-of-class submarine deployed to sea last month to begin its first operational patrol.

An official video that was prepared for the commissioning ceremony of the Dosan Ahn Changho, the first of the KSS-III boats:

The Dosan Ahn Changho class is significantly larger than previous South Korean submarines, at around 3,800 tons submerged, and is equipped with a fuel cell-based air-independent propulsion system. Each of the three initial Batch I boats has a capacity for six SLBM tubes, although these can also be alternatively loaded with cruise missiles.

Few details are known about the SLBM itself, which is variously named Hyunmoo 4-4 or K-SLBM. Reports suggest the missile has a range of 311 miles and that it could be a naval variant of the Hyunmoo 2B ballistic missile.

The SLBM is just one of several missile programs that Seoul has developed in response to North Korea’s expanding missile capabilities. While some of these are more powerful land-based weapons, an SLBM offers a much more survivable option, which is of particular importance bearing in mind the risk of a preemptive strike from the North.

In general, Seoul’s missile projects have been enabled by the lifting of a series of earlier restrictions on missile range, that had existed under a bilateral agreement with the United States. These limits were scrapped entirely under a deal between U.S. President Joe Biden and the previous South Korean President Moon Jae-in.

Clearly, long-range missiles in general, and the SLBMs carried by the KSS-III submarines, play squarely into the KMPR doctrine.

Should the North launch a nuclear attack, the survivability of the submarines should allow a conventional response, even if land-based missiles may have been taken out already. In this way, the SLBMs could be targeted against regime targets and command and control facilities, hitting them with much less notice and more kinetic power than a cruise missile barrage. The fact that this quasi-second-strike capability exists should also help dissuade North Korean aggression.

Importantly, both the carrier and SLBM-armed submarines would offer South Korea ways to project power beyond the context of a peninsular conflict. The carrier project in particular seemed to be about more than just North Korea, with relevance also to potential contingencies involving regional rivals like China and Japan. The new administration’s apparently shifting stance on China may also have contributed to funding for CVX now being cut. Finally, a carrier would also have allowed deeper participation in large-scale naval maneuvers with the United States and others, much like the drills currently taking place in the Western Pacific.

In contrast to the carrier effort, however, Seoul’s submarine program appears to be very much in an ascendancy.

The Batch II boats in the Dosan Ahn Changho class are expected to increase SLBM capacity from six tubes to 10.

Beyond these, there has also been discussion of a potential follow-on nuclear-powered submarine design. With the previous missile restrictions removed, these (and previous) submarines could potentially also be armed with new SLBMs with considerably greater range. And, while the KMPR initiative is currently based around conventional weapons, there has long been speculation that Seoul might eventually commit to developing nuclear warheads, too. SLBMs would be an obvious choice for these if pursued.

What is especially notable about South Korea’s burgeoning SLBM program is that it appears to be rapidly threatening to eclipse that of the North. While Pyongyang has paraded nuclear-armed SLBMs on a fairly regular basis, its efforts to actually field these as part of a meaningful sea-based deterrent have so far achieved only very limited success.

As well as the SLBM capability, which could also allow Seoul to reduce its reliance on the United States when it comes to deterrence, submarines can also take on many other roles in a potential conflict with North Korea, including surgical strikes using cruise missiles, minelaying, insertion of special forces and, not least, hunting down North Korea’s own SLBM-armed submarines, the Sinpo class.

As it stands, it looks as if Seoul has decided that the benefits of an SLBM-armed submarine force outweigh the potential of an aircraft carrier, for now at least.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com