A sprawling bipartisan proposal to rebuild America’s long-ailing shipbuilding industry was introduced by a group of lawmakers last week. Known as the Shipbuilding and Harbor Infrastructure for Prosperity and Security (SHIPS) for America Act, the ambitious bill seeks to overhaul and restore America’s military and civilian maritime capacity and capabilities. These industries have increasingly fallen behind over the decades, and concerns have grown urgent as China’s shipbuilding capacity continues to dwarf America’s in many respects.

“This is the first major piece of maritime reform since the Merchant Marine Act of 1970,” Sal Mercogliano, a former Military Sealift Command (MSC) mariner and associate professor of history at Campbell University, told USNI News’ Mallory Shelbourne this week. “So you’re talking about 55 years since we’ve had anything like this.”

“By supporting shipbuilding, shipping, and workforce development, it will strengthen supply chains, reduce our reliance on foreign vessels, put Americans to work in good-paying jobs, and support the Navy and Coast Guard’s shipbuilding needs,” one of the bill’s co-sponsors, Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), a Navy veteran and the first U.S Merchant Marine Academy graduate elected to Congress, said in a statement.

Among its many provisions, the SHIPS Act would require the Navy to develop a strategy for a “rearm-at-sea” capability for the surface fleet. It doesn’t specify which platforms would get the capability, but the sea service has already been testing systems for reloading vertical launching system (VLS) missile cells at sea, and did it successfully for the first time in October. In that instance, the MSC’s dry cargo ship USNS Washington Chambers (T-AKE 11) transferred an empty VLS weapon container to the USS Chosin (CG-65), a Ticonderoga class cruiser, while underway off southern California.

Such a capability would be vital during a war against China in the expanses of the Western Pacific, one that would likely involve a heavy volume of missile fire by Navy warships far from ports. Being able to reload at sea helps mitigate such a challenge.

The act would also help private shipbuilders to better service military and commercial customers by requiring the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard to assess and integrate commercial best practices for designing, repairing, and building vessels.

As the United States seeks to get its shipbuilding house in order, China’s Military-Civil Fusion strategy in shipbuilding has already given the country a massive long-term edge in building commercial, naval and support vessels relatively efficiently and cheaply compared to America and its allies.

Some in the U.S. have started to call for similar integration of commercial and naval shipbuilding.

“The United States has substantial latent shipbuilding, sustainment, and repair capacity, including aging but not obsolete capital assets, a strong base of potential skilled-trade labor, and a middle-management and engineering talent base that has become geographically separated from shipyards,” McKinsey and Co., a consultancy, wrote in June. “Rapidly increasing output requires tapping into this latent capacity quickly and confidently.”

The legislation would also mandate a plan for how the Defense Production Act could be used to enhance shipyard infrastructure, the defense shipyard industrial base, and port infrastructure.

It would work to bolster smaller shipyards, providing $100 million annually from Fiscal Year 2025 to 2034. A loan fund would also be stood up for reflagging vessels or “converting a vessel to a more useful military configuration.”

The SHIPS Act further seeks to expand the American shipyard industrial base for military and civilian vessels by way of a 25% tax credit for such investments, while establishing other financial incentives to encourage innovation in shipbuilding and repair.

A U.S. Center for Maritime Innovation, with hubs across the country, would work to accelerate next-generation ship design, alternative energy and manufacturing as well.

All these steps seek to help the Navy and American shipbuilding industry that struggles to get new platforms out on time and on budget, while supporting those that are already in the water. The latter has been a massive challenge as the Navy’s fleet ages while demands for more hulls increase. Crumbling shipyards around the U.S. and a limited number of them that can support mainline military vessels is a huge problem that has led to major delays in maintenance, greatly harming available end strength. It is also of major concern if ships were to get damaged in battle during a conflict and need to be regenerated quickly. While some improvements and investments have been made in upgrading shipyards, it is still a glaring and highly concerning issue.

In the shipyards, America’s shipbuilding capacity was in decline even before the end of the Cold War, and shrunk more afterward. It is at a particularly low point, an ebb helped along by the yards’ struggle to attract a sufficient workforce.

“Currently, the United States and China have relative parity in overall economic output,” retired Marine Corps Maj. Jeffrey L. Seavy, noted in the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings publication in April. “In terms of shipbuilding, however, China has 46.59 percent of the global market and is the largest builder, with South Korea second at 29.24 percent, and Japan third with 17.25 percent. The United States has a relative insignificant capacity at 0.13 percent.”

To offset domestic shortfalls, Navy leaders have been exploring the possibility of repairing U.S. ships in Korean or Japanese shipyards, although by law American warships can’t be built outside of the states.

The nation’s sealift capacity has been deteriorating as well. U.S. Transportation Command leaders told Congress in April that sealift readiness was a primary concern, and that 17 of the 47 Ready Reserve Force ships were more than 50-years-old, which was dragging readiness rates to alarming levels.

To bolster the U.S. sealift fleet, the bill would allow the U.S. to enter into agreements with treaty allies to meet sealift requirements. Already, the Navy is testing the waters for using Pacific allies for such logistics needs.

The U.S.-flagged international fleet would also grow to 250 ships in 10 years via a “Strategic Commercial Fleet Program” to establish “a fleet of commercially operated, U.S.-flagged, American crewed, and domestically built merchant vessels that can operate competitively in international commerce,” according to a summary of the bill provided by Kelly’s office.

“The United States has fewer than 200 oceangoing vessels of the United States, of which only approximately 80 vessels participate in international commerce, compared with more than 5,500 Chinese documented vessels,” the legislation states.

“In order to increase the fleet rapidly, carriers may also submit a bid to bring a foreign-built vessel into the fleet and reflag it,” the bill states.

In a nod to how U.S. officials view China as a threat beyond its military, the bill also calls for an evaluation of the Chinese government-affiliated National Transportation and Logistics Public Information Platform, or LOGINK.

The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission warned in 2022 that LOGINK “potentially provides the Chinese Communist Party access to data collected and stored on the platform and could enable the Chinese government to gain insights into shipping information, cargo valuations via customs clearance forms, and destination and routing information.” LOGINK, which operates in more than 20 global ports, could undercut U.S. firms economically and expose supply chain vulnerabilities, according to the commission.

On the personnel side, the bill would give the Navy secretary additional authority to recruit and retain civilian mariners working under the MSC. These mariners would play a vital role manning ships moving troops and materiel in the event of a war with China, but the command has struggled with finding enough people. MSC announced in November that it would sideline 17 support vessels to ease the strain on the civilian mariner workforce amid personnel shortages, USNI News’ Mallory Shelbourne reported.

To keep such civilian mariners around, the bill would also allow merchant mariners or U.S. shipyard employees to qualify for loan forgiveness if they are employed on an American vessel or shipyard for 10 years. Mariners who have received the Merchant Marine Expeditionary Medal or other mariner medals for service in a designated combat zone would also become eligible for G.I. Bill benefits under the legislation, if they were not already eligible.

To find new talent, the bill would enact targeted recruiting campaigns run by private marketing firms to promote maritime industry careers, and would have military recruiters recommend at-sea or shipyard careers to prospects who don’t qualify for military service.

If passed, the bill would also raise the profile of maritime security affairs by creating a maritime security advisor role within the White House that would lead whole-of-government decisions about American maritime strategy.

The SHIPS Act was introduced last week by co-sponsor Kelly and U.S. Rep. Mike Waltz (R-Fla.), a supporter of the plan and President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for national security advisor.

Other sponsors include Sen. Todd Young (R-Ind.), U.S. Rep. John Garamendi (D-Calif.), ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Readiness, and U.S. Rep. Trent Kelly (R-Miss.), chairman of the House’s Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee whose home state hosts several major shipyards.

The legislation is paid for via a Maritime Security Trust Fund, similar to existing highway and aviation trust funds. A Kelly spokesperson told TWZ that the bill authorizes $18.1 billion over a decade. The legislation states those funds will come from duties, fees, and penalties imposed on vessels in international commerce, regular tonnage tax proceeds, special tonnage taxes, light money, duties imposed on foreign nations and tariffs, which are all collected by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Industry appears to support the legislation, as its announcement features a bevy of American maritime interests, including shipbuilding associations, shipbuilding corporations, academia and defense groups.

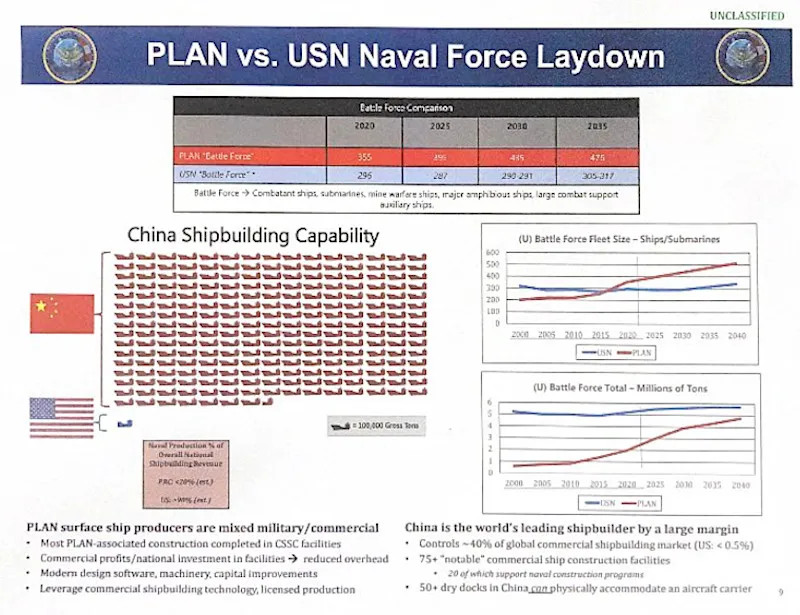

TWZ has regularly reported on the shortfalls of the U.S. shipbuilding industry over the years. A leaked U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence slide revealed in 2023 that China’s shipbuilders are believed to be more than 200 times more capable of producing surface combatants, support ships and submarines than their American counterparts. This is due to the country being a major shipbuilder globally and the ability to use its yards to build military and commercial vessels as needed. Such a revelation underscored longstanding worries about the U.S. Navy’s ability to challenge Chinese fleets, or sustain its forces afloat, during a war.

Reporting at the time explained the significance of that slide:

“The most eye-catching component of the slide is a depiction of the relative Chinese and U.S. shipbuilding capacity expressed in terms of gross tonnage. The graphic shows that China’s shipyards have a capacity of around 23,250,000 tons versus less than 100,000 tons in the United States. That is at least an astonishing 232 times greater than the United States.”

At more than 370 ships by the Pentagon’s latest count, in terms of hulls alone, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) already exceeds the Navy’s battle force fleet of nearly 300. The ONI slide revealed that, by 2035, the gap between Chinese ships and U.S. vessels will widen substantially.

Navy leaders have at times in recent years sought to downplay the numeric differential between the rival fleets, as TWZ reported last year.

Much legislation gets introduced with great fanfare and urgency, only to fall by the wayside once the sausage-making commences. Whether the SHIPS Act suffers the same fate remains to be seen. It would seem to be inline with incoming President-elect Trump’s general view of the need to revitalize American industrial production. Stabilizing the shipbuilding and vessel support base would seem to be part of that general concept, along with the goal of building a stronger Navy.

Either way, it signals that the U.S. maritime universe’s long-chronicled deficiencies are now attracting attempts at meaningful higher-level action.

Contact the author: geoff@twz.com