Two of the most capable military cargo ships in U.S. inventory are among the vessels now stuck in Baltimore following the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge yesterday. The two members of the Algol class, which are also some of the fastest cargo vessels of their general size anywhere in the world, and two other reserve sealift ships were in port in Baltimore when the incident occurred. Readers can first get up to speed on what happened to the Francis Scott Key Bridge, which was struck by the container ship MV Dali, with The War Zone‘s initial reporting on the incident here.

At the time of writing, the movement of ships in or out of the Port of Baltimore continues to be suspended indefinitely due to the incident yesterday, which also remains under investigation. Six members of a construction team that was working on the bridge when the Dali struck it are now presumed to have died. Two other workers from that team were rescued, one of whom was hospitalized. There have been no other reported casualties and authorities say a mayday call from the crew of the Dali helped prevent a larger disaster. The ship remains pinned under a collapsed section of the Francis Scott Key Bridge and is severely damaged. What the timelines might be for clearing the channel and repairing the bridge is unclear.

“I’ve directed my team to move heaven and Earth to reopen the port and rebuild the bridge as soon as humanly possible,” President Joe Biden said yesterday. “It is my intention that the Federal government will pay for the entire cost of reconstructing that bridge.”

“This port is the top vehicle handling port in the United States,” Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg told NPR‘s “Morning Edition” today. “We can’t wait for the bridge work to be complete to see that channel reopened. There are vessels that are stuck inside right now and there’s an enormous amount of traffic that goes through there. That’s really important to the entire economy.”

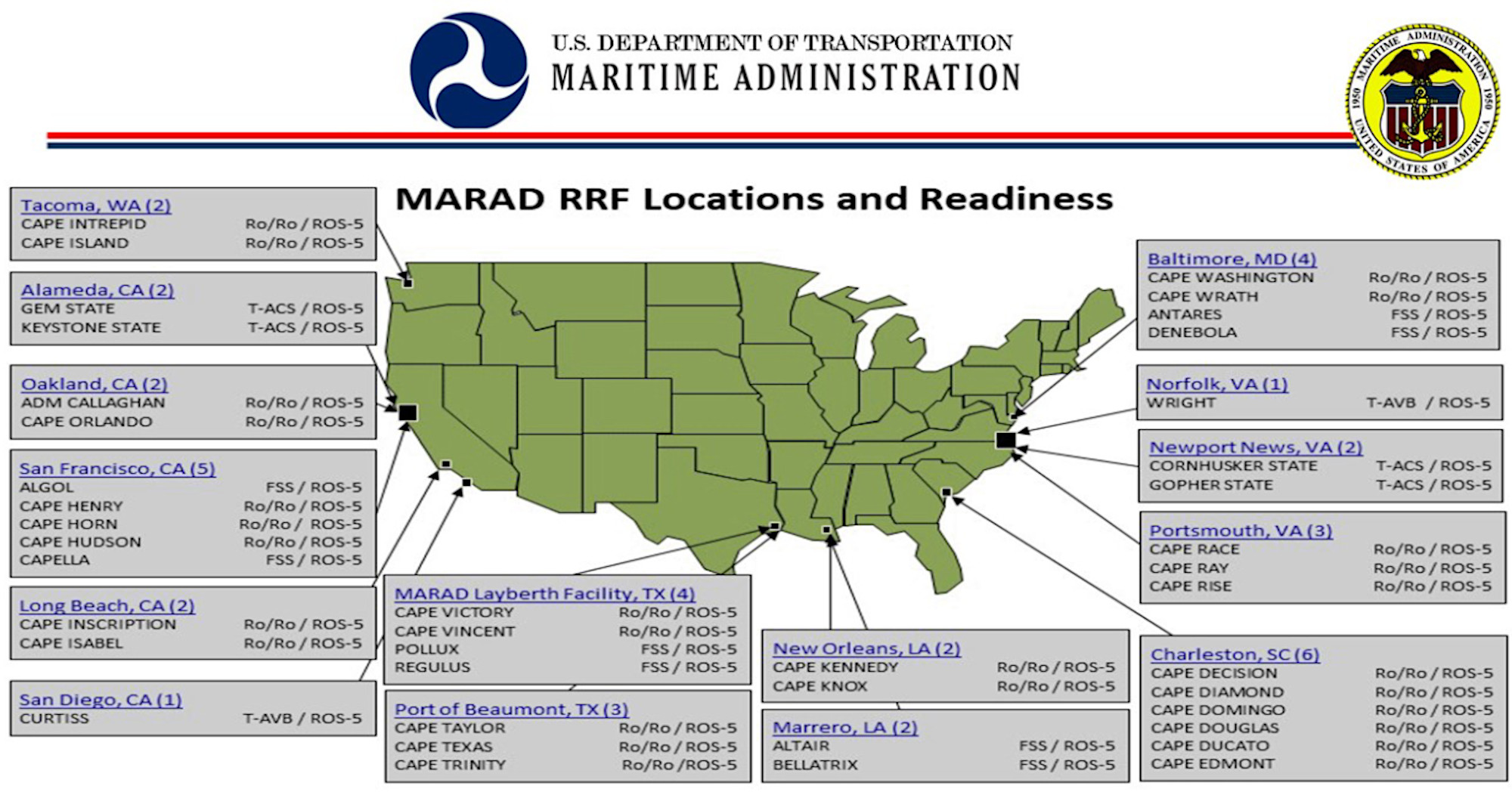

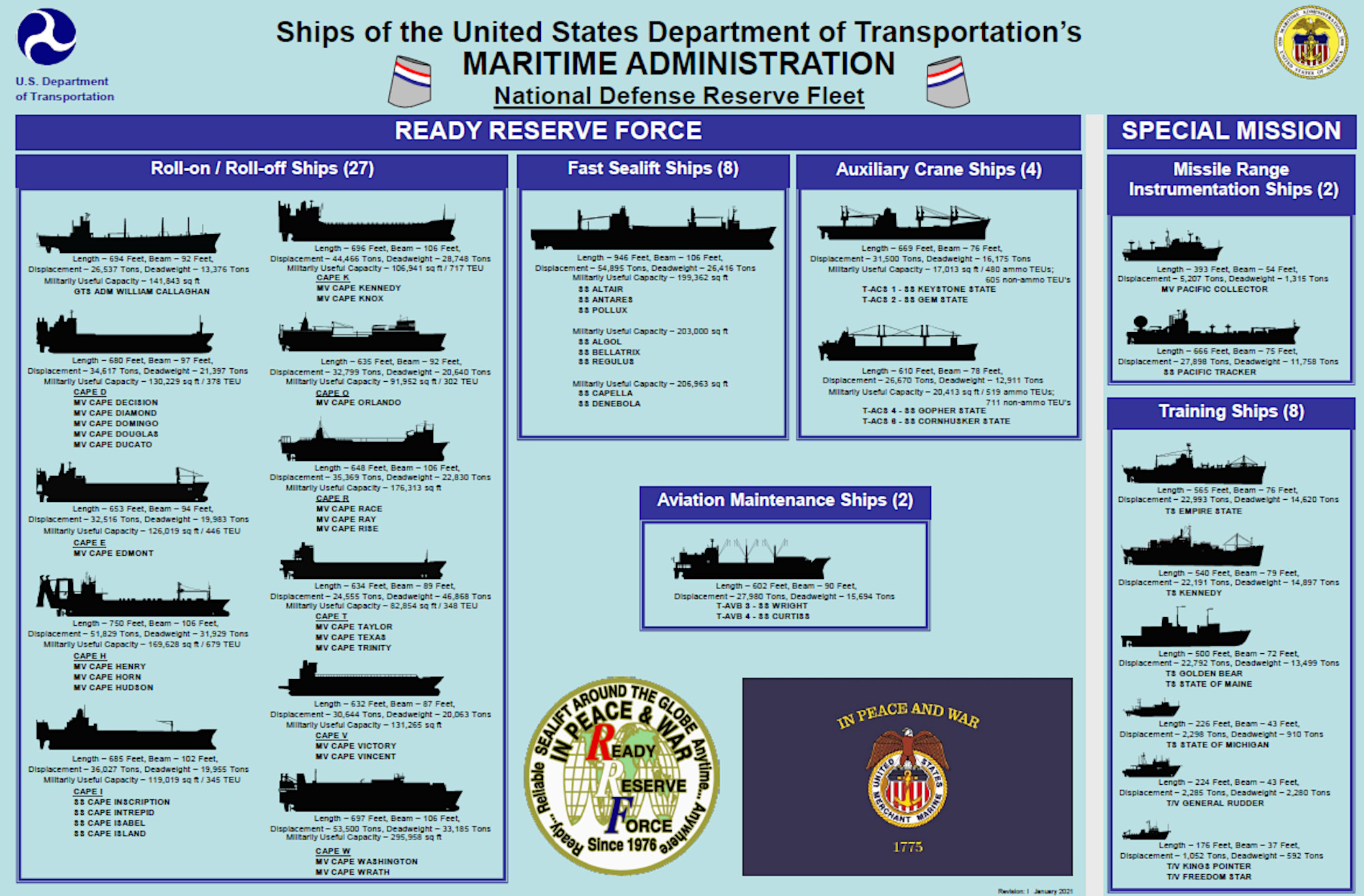

The vessels now stuck in Baltimore include the Algol class SS Antares and SS Denebola, both of which are part of the Ready Reserve Force (RRF) fleet. The Transportation Department’s Maritime Administration (MARAD) manages the RRF and its ships are crewed by civilian merchant mariners. RRF ships fall under the control of the U.S. Navy’s Military Sealift Command (MSC) when they are activated for operations. The activation process for RRF ships, which are typically kept at a reduced operating status (ROS) with a skeleton crew until called upon, can take between five and 10 days depending on the vessel in question.

Two more members of the RRF fleet, the roll-on/roll-off cargo ships MV Cape Washington and MV Gary I. Gordon, are also in Baltimore. Cape Washington‘s sister ship MV Cape Wrath is homeported there, too, but online tracking data indicates that it is still somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean sailing west after leaving Belgium earlier this month.

All of the RRF ships in Baltimore are categorized status-wise as “ROS-5,” meaning they should be capable of heading out within five days of getting an activation order under normal circumstances, according to MARAD. The War Zone has reached out to MARAD for more information about the RRF ships in Baltimore and what it is doing in response to yesterday’s incident.

Regardless, the current stranding of the Antares and Denebola in Baltimore is especially notable. The pair represents a quarter of the entire Algol class, which, as already noted, are especially fast and otherwise capable cargo ships. Originally built in the 1970s in shipyards in the Netherlands and what was then West Germany for the now-defunct U.S. commercial shipping company SeaLand, have a publicly stated top speed of 33 knots. Similarly-sized cargo ships more typically sail along at between 13 and 24 knots, depending on their exact configuration and load.

The Navy does have a fleet of Spearhead class Expeditionary Fast Transports, which are capable of hitting speeds of at least 35 knots, and reportedly up to 45 knots, but these are much smaller and less capable from a raw cargo-carrying perspective than the Algols. You can read more about the Spearheads, a significant number of which the Navy is looking to decommission in the coming years, here.

For a time, the Algol class, which SeaLand also referred to as SL-7s, were the fastest conventional steam-powered cargo ships in the world. The propulsion systems on each of these vessels consist of two large boilers that produce steam to run a pair of turbines that in turn drive two propeller shafts. Today, the speediest vessels in this category are Maersk’s B class container ships, also known as the Boston class, the first of which was built in the mid-2000s. These ships can reportedly hit top speeds of around 37 knots, though they are designed to cruise at around 29 knots.

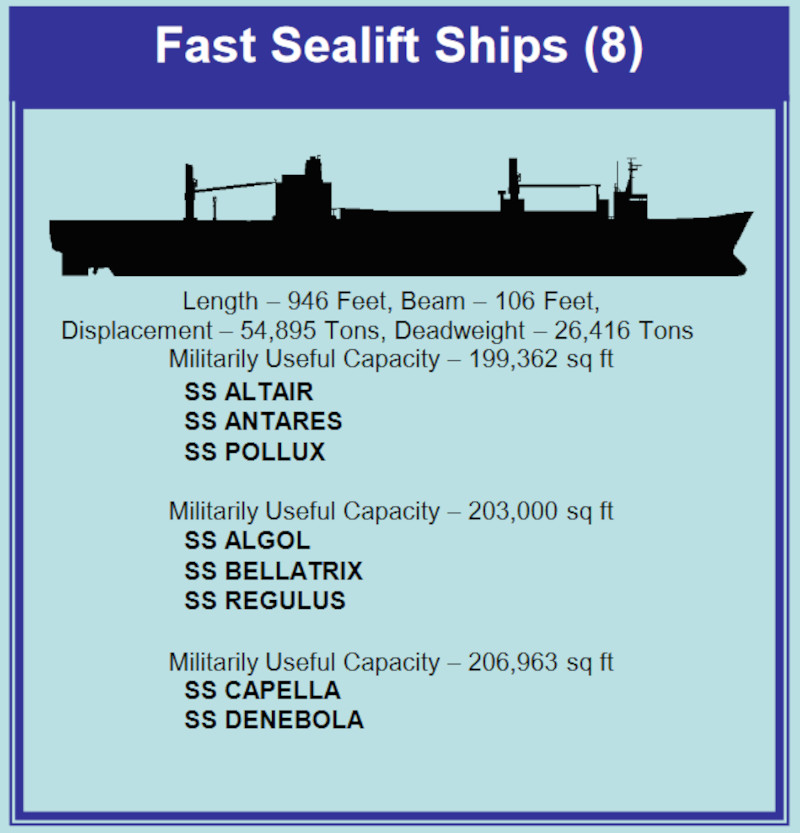

Though fast and capable, SeaLand found the SL-7s overly expensive to operate and sold all eight examples to the U.S. government in the 1980s. These were initially assigned directly to MSC and were given new USNS names. Modifications were also made to ships, which also subsequently dubbed Fast Sealift Ships (FSS), to better optimize them for carrying vehicles and otherwise for military use. In the late 2000s, the Algol class vessels were removed from Navy service and turned over to MARAD, at which point their USNS prefixes were replaced with civilian SS ones.

The individual members of the Algol class, which all have stated displacements of 54,895 tons, currently fall into three distinct subclasses with slightly different internal configurations, according to MARAD as can be seen below. Antares is among three with a “Militarily Useful Capacity” of 199,362 square feet, while Denebola is one of two 206,963 square feet of similarly useful internal space. The capacity of the remaining three ships is 203,000 square feet.

Algol class have been called upon multiple times since they entered U.S. service. Just five of these ships were responsible for transporting 20 percent of U.S. cargo sent from the United States to Saudi Arabia during the first phase of Operation Desert Shield in the immediate run-up to the First Gulf War. The ships would go on to deliver 13 percent of all cargo that arrived in Saudi Arabia from the United States in the full course of that conflict.

The U.S. military subsequently used Algols to support operations in Somalia and the Balkans in the 1990s, as well as the opening phases of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in the early 2000s.

The ships have been utilized for large exercises and humanitarian relief missions, as well. The picture below shows cargo being unloaded from the Algol class USNS Altair onto a U.S. Army LACV-30 hovercraft, which you can read more about here, during Exercise Gallant Eagle 86.

The MV Cape Washington and MV Gary I. Gordon represent a smaller percentage of the nearly 30 roll-on/roll-off cargo ships in the RRF fleet. There are additional roll-on/roll-off cargo ships directly assigned to MSC, as well. Still, Cape Washington and Cape Wrath, the latter of which looks to escaped being caught up in the current situation in Baltimore, are two of the largest such vessels in RRF inventory, with 295,958 square feet of Militarily Useful Capacity, according to MARAD. The Gary I. Gordon‘s reportedly has 284,064 square feet of internal cargo space, plus 49,991 more square feet on its deck.

This all comes at a time when U.S. military sealift capacity is in as high demand as ever, especially as the Department of Defense continues to focus its efforts on preparing for a potential high-end conflict in the Pacific against China. Sealift is also particularly relevant in light of the current security situation in Europe due to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and concerns about its potential to spill over elsewhere. The U.S. military has also used commercial cargo ships to help get aid bound for Ukraine, including M1 Abrams tanks and M2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicles, to intermediate staging points in Europe.

U.S. sealift ships also continue to be available to help respond to humanitarian crises and other contingencies short of an actual conflict. The Bob Hope class Roy P. Benavidez, another RRF roll-on/roll-off cargo ship, is currently on its way to the Mediterranean Sea carrying equipment that will be used to establish a temporary off-shore pier intended to help increase the flow of humanitarian aid into the Gaza Strip. You can read more about that operation here.

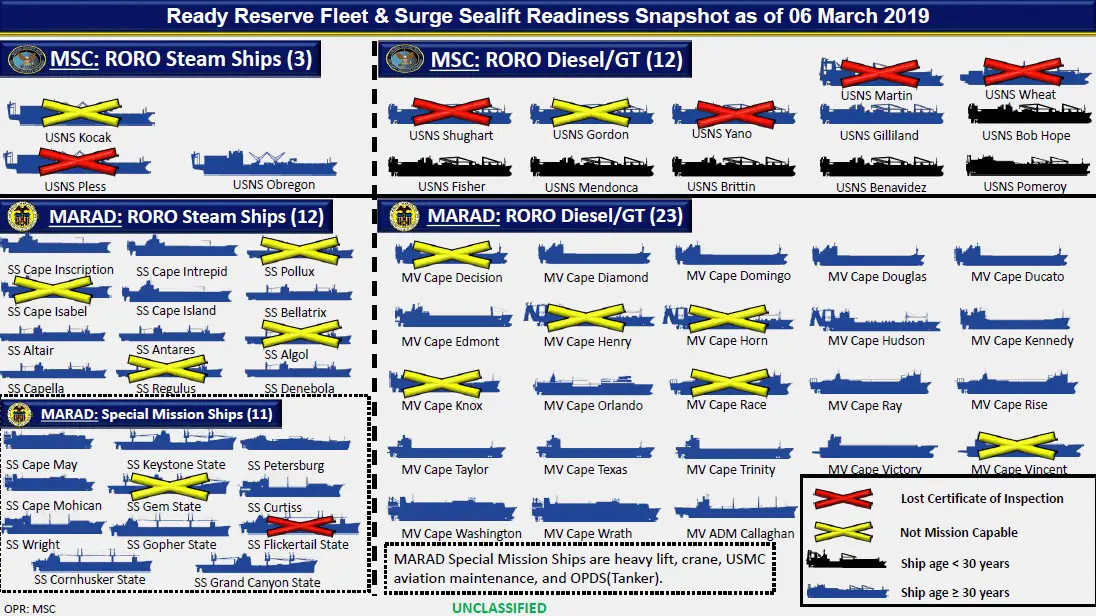

For years now, there have been concerns that existing U.S. military sealift capacity is insufficient to meet current demands, let alone what would be required in the event of a major conflict breaking out. As of 2019, at least 11 RRF ships, including three of the eight Algols, were not mission capable at all, according to MARAD.

The current state of readiness of the RRF fleet as a whole is unknown. However, at a hearing last year, MARAD Director Ann Phillips, who is also a retired Navy Rear Admiral, told members of the House Armed Services Committee that she “was not at all confident” that all RRF ships could be activated if required, according to USNI News.

The core of the Navy’s current plan for sustaining and potentially expanding sealift capacity is to continue helping to fund MARAD’s acquisition of commercial cargo vessels for conversion to military use. The Department of Transportation, through MARAD, has also implemented a new initiative utilizing privately-owned ships to help bolster sealift capacity.

Yesterday’s incident in Baltimore now presents an additional complication for the RRF fleet, with four of its ships, including the two examples of the highly capable Algol class, blocked in port.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com