Defense contractor Anduril has rolled out a new, readily deployable undersea surveillance system called Seabed Sentry, which uses networks of small and relatively low-cost modular sensor nodes. A novel sonar array with a design influenced by the extendable arms on satellites is the main sensor being paired with it now. Expanding fleets of quieter and otherwise more modern submarines, especially in Russia and China, as well as growing threats to critical undersea infrastructure, are driving demand for more and better ways to monitor what happens beneath the waves across the Western world.

Anduril has already been working on various elements of Seabed Sentry for around a year. The system leverages various prior developments, including Lattice, the company’s proprietary artificial intelligence-enabled autonomy software package. The Seabed Sentry name is a callback to Anduril’s first product, the land-based Sentry, which is designed to monitor for threats in the air and on the surface.

A separate firm, Ultra Maritime, is also providing its Sea Spear sonar for use on Seabed Sentry through an exclusive partnership with Anduril.

“Surface and air vehicles can operate with clear lines of sight and reliable connectivity, but the ocean is vast and opaque, leaving current autonomous subsea sensing and communications technology operating slowly in silos. We need a network for real-time data exchange to reliably transmit information into action,” per a press release from Anduril. “Seabed Sentry fills connectivity and perception gaps, enabling maritime awareness and kill chains in ways not currently possible without high expense. With superior endurance lasting months to years, a depth rating exceeding 500 meters, a payload capacity of over 0.5 m³, and a modular, reusable design, Seabed Sentry is built to surpass existing seabed surveillance solutions. It offers operators greater flexibility and capability in even the most challenging underwater environments.”

“Unlike fixed seafloor surveillance systems – which are expensive to place and maintain – Seabed Sentry is a network of ‘cable-less’ deep-sea nodes that sense, process, and communicate critical subsea information at the edge in real time,” the release adds. “It has an open systems architecture for rapid integration of first or third-party sensors and payloads customized to the commercial or defense missions including seabed survey, marine pattern of life building, port security, critical infrastructure protection, anti-submarine warfare, and anti-surface warfare.”

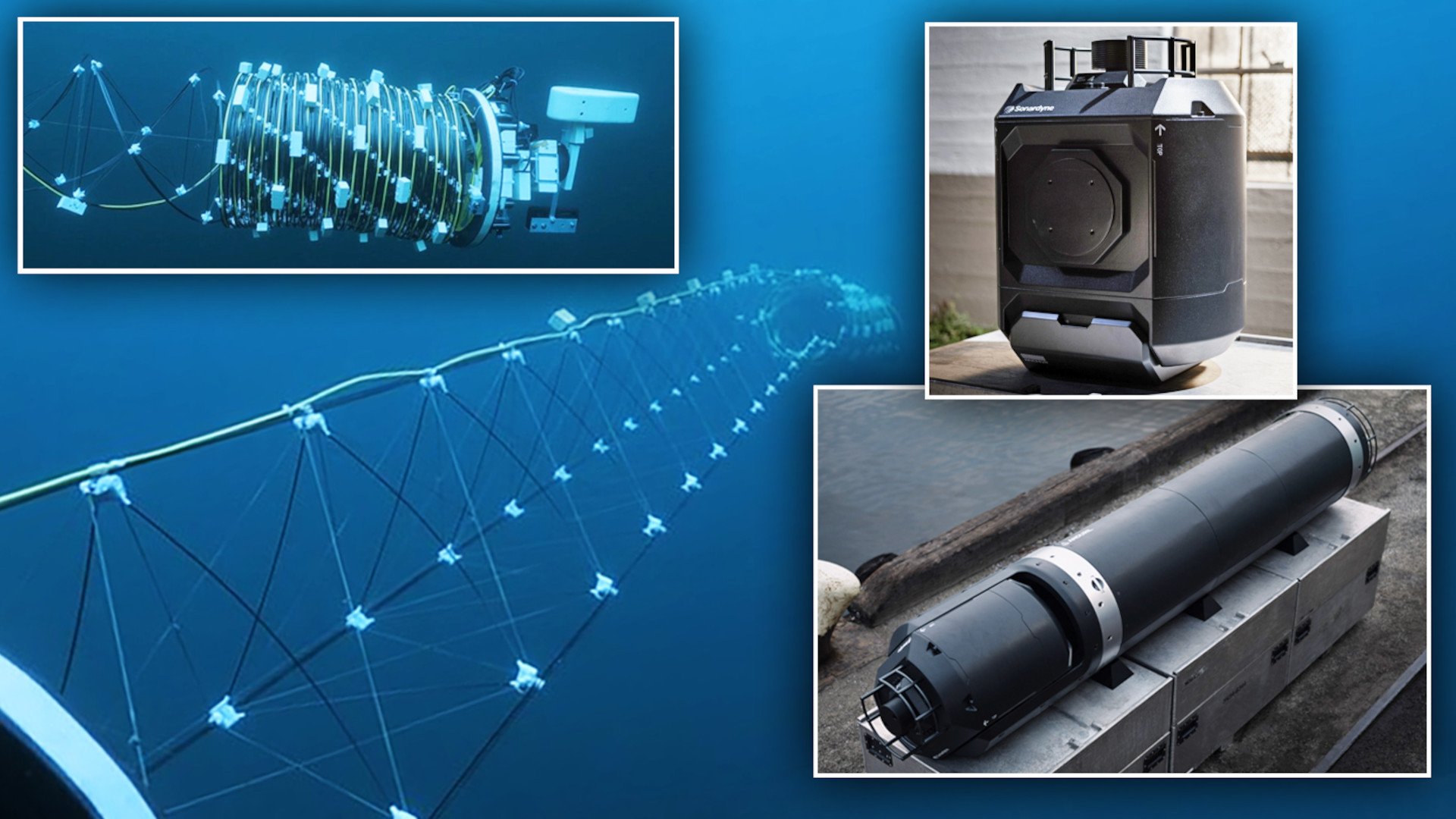

At the core of the Seabed Sentry system is an array of cylindrical buoy-like nodes that are 21 inches in diameter and roughly eight feet (two and a half meters) long. Each one has a modular payload bay and an anchor to keep it in place underwater after deployment.

“The head of it is kind of where all the comms and compute [communications and computing capabilities] live,” Dr. Shane Arnott, Senior Vice President for Engineering at Anduril and the company’s maritime lead, told TWZ. “And then the tail of it, which you’ll see, is where we can host flexible payloads.”

In addition to being physically modular, Seabed Sentry is also an open-architecture system, which helps make it easier to upgrade existing capabilities and integrate hardware and software. How long a Seabed Sentry node can remain deployed will depend on its exact configuration, but Anduril says the nodes should be able to remain in place for multiple months at a time. After that, they can be recovered and reused.

“When it’s done, we can talk to it, and it says, ‘Yep, I’m ready to be recovered,'” Anduril’s Arnott explained. The anchor “will sever itself, and the system is positively buoyant, so it comes to the surface.”

“We recover it, and then we can refit it, and then send it back on mission again,” he continued. “The team can either just scrape the barnacles off it, recharge it, and throw it back in, or … there could be a new mission, new payload that needs to be fitted to it – recharge it, new payload, and off you go again.”

As already noted, Ultra Maritime’s Sea Spear is the premier sensor payload for Seabed Sentry at this point, though it is expected to be just one one of many options in the future.

Sea Spear is similar in form and function to cable-like sonar arrays towed behind surface ships, but it uses a unique extendable trusswork to allow it to extend from and retract back into the Seabed Sentry node. The exact configuration of the sonar for use with Anduril’s underwater surveillance system is still being finalized, but it is expected to be tens of meters long when fully extended.

“We design and build towed arrays today for multiple reasons. … For torpedo defense, for low-frequency surveillance, for different things. So it derives from that,” Ultra Maritime’s President & CEO Carlo Zaffanella also told TWZ. “But the trusswork and the creativity behind that, actually, it takes a hint from from some work that NASA did for space, where you needed [a] very lightweight, extendable arm that could suspend in space. When we make something neutrally buoyant in the water, [there are a] very similar sort of physics involved.”

Once extended, Sea Spear functions primarily in a passive mode. However, it can be used in combination with other systems, including air-dropped sonobouys with active sonars, to provide additional functionality.

“So, you get a P-8 [Poseidon maritime patrol plane] that’s flying over, it throws sonobuoys, and the array can listen for that, right? [It] can listen for reflections off of the submarine,” Zaffanella explained. “You could do the same off from a UUV [uncrewed underwater vehicle]. You might transmit and then receive using the, you know, the great receiving capability that Sea Spear has.”

Getting whatever data Sea Spear and any other sensors on Seabed Sentry collect where it needs to go presents its own challenges that Anduril and Ultra Maritime have been working hard to address.

If “you turn your iPhone on and you start streaming a whole bunch of pixels in, if you [want to put that] data back out, well, you can sort of do that with a phone, because in the air you can transmit a whole lot of bandwidth. In the water, you can’t. So, you couldn’t possibly take all of that information and just constantly pump it through acoustic communications,” Zaffanella noted. “Instead, what we do is we use our sonar algorithms that we’ve been developing for many years, and using in many applications, and using modern AI and ML [artificial intelligence and machine learning], we make it possible to run them right at the tactical edge.

“So we put processing, low power, specialized, right there … and all of that sonar information is processed sort of in real time. So the only thing that you have to acoustically communicate back away from Seabed Sentry is information like a track or a detect, right?” he continued. “What Seabed Sentry then does is it’s capable of taking that data and communicating it to some other vessel. Could be another Seabed Sentry. Could be the unmanned vessel that delivered the thing in the first place. Could be a manned vessel. Could be another relay. And using Anduril’s Lattice framework, of course, we can then put multiple of these [nodes] together, and you can create a mesh network where you have this easily deployable, producible in volume, extendable array.”

This kind of onboard AI/ML-assisted processing is becoming increasingly prevalent elsewhere, even on aerial platforms, to help manage ever larger volumes of data.

“Some of the stuff that we’re bringing our magic to, if you will, is through Lattice, where we’ve kind of pioneered on the edge [of] acoustic processing. Like this is actually a super wicked [hard] problem,” Anduril’s Arnott also told TWZ. “So we figured out how to put Lattice on these nodes in a low power setting … and optimizing when they talk to each other in order to maintain their persistence.”

The kind of persistence and broad area undersea surveillance coverage that Anduril, together with Ultra Maritime, is aiming for with Seabed Sentry has historically been provided by large networks of static hydrophones that are extremely costly to establish, operate, and maintain. The U.S. Navy’s Cold War Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) network is perhaps the best-known example of such a system. Portions of SOSUS do remain in service, but are now used more for scientific research than watching for foreign submarines. SOSUS has been largely supplanted operationally by a mix of fixed sensor arrays, surface ships towing sonar, and processing stations ashore known collectively as the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS).

The general size and scope of undersea surveillance networks like SOSUS and IUSS can make it easier for opponents to map them out, even when it comes to underwater components that may not be publicly acknowledged.

“These are cabled systems. They’re insanely expensive, like, just crazy expensive, almost impossible to upgrade, other than ripping them out, and putting new stuff in,” Arnott highlighted. “And with a little bit of intelligence, the threat can actually track where these nets are, because you can see these cable laying ships from space, right?”

“Some of these cabled subsea networks are there for a reason, and you know, the host nations aren’t worried that the bad guys know where they are. So there’s definitely purposes for these wired networks,” Arnott added. “This [Seabed Sentry] can actually work in conjunction with those wired networks. So we intend that this could be an extension, as well, like a wireless extension … if you will, leveraging some of those networks. So it’s not kind of an either or, but it’s really a different tool in the toolkit.”

Anduril notably envisions Seabed Sentry nodes being emplaced and recovered using UUVs, as well as via ships on the surface. This, in turn, would allow arrays to be deployed covertly or clandestinely, and in denied or otherwise sensitive areas. This also makes the system more unpredictable overall, which is a major advantage.

“So we can load up the Dive XL [a large UUV in Anduril’s larger portfolio also known as Ghost Shark] with about a dozen of these things, go and place them on the sea floor wherever you want, [and] do that completely covertly [or] clandestinely,” Arnott said. “If you want to lay a trip wire or set a net for threats, it’s a good idea for them not to know where your security cameras are, for want of better words.”

Arnott further noted that Seabed Sentry’s networked design and high degree of modularity means that it could also be adapted to roles far beyond just undersea surveillance in the future.

“The payload bay is configurable. So the vast majority of the system is this long tube, in effect, that you can fit whatever you want in there, which could be AUVs [autonomous underwater vehicles] or things that swim out of it,” he explained. “So you could, if you can imagine, load up these things that look the same from the outside … And some of them could be comms. Some of them could be sensing. Some of them could have … effectors. So AUVs that kind of swim out of, out of the payload bay, if you will. So anything that you can fit within that payload bay that then hooks up to the ‘brain’ is possible with this.”

Seabed Sentry is inherently scalable with whatever mission sets it might be assigned, which would allow it to be employed in a very targeted manner. That could be attractive for smaller and otherwise more cost-conscious users, as well as ones interested in employing it on a much wider basis. Arnott said that the system’s flexibility has already prompted interest from potential customers looking to leverage it more as a contractor-operator service.

“So the approach that we’re taking, and we are in active conversations with customers at the moment, who are thinking about this even as a service,” Arnott said. “The whole idea is it’s at a cost point that’s so affordable that, you know, we can be constantly re-seeding these nets, if you will, that they’re they’re placing out there, and be able to change it as well, because the bad guys may figure out, ‘oh, they’ve put one of these here,’ or they get dug up, or attritted for various reasons.”

Anduril says it cannot currently name any customers or potential customers for Seabed Sentry.

There are certainly clear demand signals for new and improved undersea surveillance capabilities, and the ability to acquire and field more of those systems at lower costs, coming from the U.S. military and the armed forces of other Western countries. In particular, American officials have been warning for years now that new Russian and Chinese submarines are increasingly harder to detect and track, and present new threats, including to the U.S. homeland, as a result. Russia’s expanding fleet of ultra-quiet Yasen-M class nuclear guided missile submarines, one of which made a visit to Cuba last year, are often held out as particularly concerning. UUVs are also emerging as a problem set that could outpace crewed submarines.

“The trend of approaching our coast from both Russia[n] and Chinese submarines is increasing,” U.S. Air Force Gen. Gregory Guillot, head of U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), told members of Congress during a hearing just yesterday. “We need an expanded undersea detection capability to ensure that we are aware of these and can properly posture to defend against submarine launched cruise missiles or ballistic missiles.”

The U.S. Navy and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) have already been working on various new undersea surveillance capabilities, including lower-cost systems that could be employed in a distributed manner, in recent years.

The underwater threat ecosystem already goes well beyond just submarines launching missiles at targets ashore and is continuing to expand in scale and scope. Incidents involving damage to undersea oil and gas pipelines and cables used to support sensor and communications networks, many of which are increasingly believed to be deliberate attacks, are on the rise, especially around Taiwan and various parts of Europe. In January, NATO went so far as to launch a named operation, Baltic Sentry, to address growing threats to critical underwater infrastructure in the Baltic Sea. That same month, a related United Kingdom-led effort, Nordic Warden, also kicked off in the Baltic region.

“The subsea [domain] is kind of the major highway for energy and information infrastructure for the planet. Just on the information front, open source is over 500 subsea cables that are pushing information around,” Arnott noted while talking to TWZ about Seabed Sentry. “And, depending on who you believe, it’s between 95 and 99 percent of all internet traffic [that] flows over these cables. It’s like 1 percent goes over space.”

“So much of that critical [undersea] infrastructure is basically unsecured at this stage,” he continued. “So the greatest vulnerabilities for many nations for their energy and information needs are under the waves, and very few people are talking about it.”

Seabed Sentry is now central to Anduril’s pitch for a way to improve keeping tabs on submarines and other underwater threats to friendly assets ashore and below the waves.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com