We now have a good look at the next LPD-17 San Antonio class amphibious warfare ship, the future USS Richard M. McCool Jr., which is the first to feature the new Enterprise Air Surveillance Radar, or EASR. McCool and its sister ship USS Fort Lauderdale differ significantly from earlier San Antonios in other ways, most visibly in the elimination of the two stealthy “all-enclosed composite mast” structures found on previous ships in the class. Those mast enclosures gave the class have a very distinct, futuristic look. This pair of ships represents a transitional subclass, but McCool, specifically, most reflects the full look of the forthcoming Flight II LPD-17 types.

Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) released pictures of the future USS Richard M. McCool Jr. (LPD-29) last week following the ship’s successful completion of builders trials in the Gulf of Mexico. HII’s Ingalls Shipbuilding division has two other San Antonio class ships under construction, the future USS Harrisburg (LPD-30) and USS Pittsburgh (LPD-31). Last year, the company also received a contract to build another one of these ships, the future USS Philadelphia (LPD-32). These three ships will be Flight II variants, which will follow the transitional LPD-28 and LPD-29, with Harrisburg expected to be the first of that subclass to enter service.

McCool‘s new radar, which will also be found on the Flight II San Antonios, is designated as the AN/SPY-6(V)2. It has an active electronically-scanned array (AESA) antenna array on a rotating base that is installed on a mast toward the stern of the ship. The EASR replaces the older AN/SPS-48 radar found on previous San Antonio class and many other ships ships.

EASR, which is produced by Raytheon, is part of a larger family of AN/SPY-6 AESA radars that all make use of common cube-shaped Radar Modular Assemblies (RMAs). The rotating, single array (V)2 version, which is also set to be back-fitted onto at least some Nimitz class aircraft carriers and Wasp class amphibious assault ships, as well as become a feature on existing and future America class amphibious assault ships, has nine RMAs.

The Navy is currently planning on acquire three other AN/SPY-6 variants. The largest is the AN/SPY-6(V)1 Air and Missile Defense Radar (AMDR), with four fixed arrays each with 37 RMAs, which is being fitted to Flight III Arleigh Burke class destroyers. At least a portion of the Navy’s Flight II series of Burkes are set to get the smaller (V)4 version, which also four fixed arrays, but with 24 RMAs apiece. The (V)3 is another fixed face type, consisting of three arrays with nine RMAs each, which will be installed on future Ford class aircraft carriers. The USS Gerald R. Ford itself may also eventually get this radar. You can read more about the entire AN/SPY-6 family of radars here.

Even the smaller versions of the AN/SPY-6 like the (V)2 offer massive advantages over existing phased array types like the AN/SPS-48, particularly in terms of being able to track more targets at longer ranges with greater precision and fidelity. Individual RMAs, each of which is essential its own AESA radar, can be assigned to perform different functions or work with the others in the array to focus on a single task, giving the entire system significant additional flexibility. EASR is more reliable and resilient, too. If one RMA stops working the rest of the array can continue functioning. These are just some of the many advantages. The single array V2 configuration of EASR does give up 360-degree scanning speed as it rotates instead of relying on multiple staring arrays.

For McCool and future Flight II San Antonios, specifically, the new EASR will improve the ability of the ships to spot, track, and engage incoming air and missile threats, including in electronic warfare-dense combat environments, as well as just offer better situational awareness.

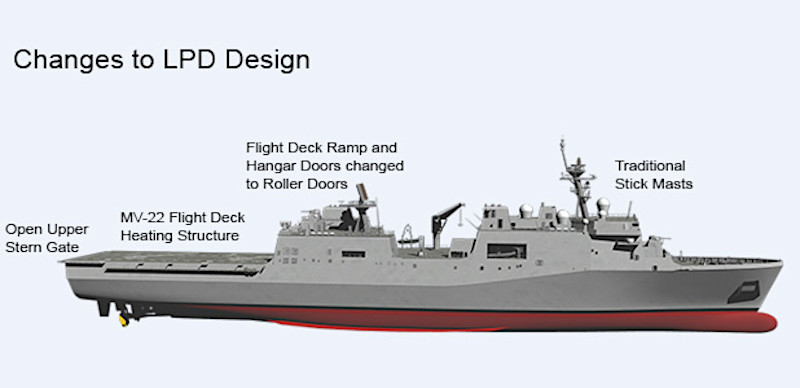

In addition to the new radar, McCool also has the same significant changes over the original San Antonio design. These alterations were first found on the USS Fort Lauderdale, which was commissioned in 2022. This includes the aforementioned deletion of the stealthy masts with more traditional-looking steel masts fitted in their place. The previous masts were made with composite materials and were the largest composite structures the Navy had ever installed on a steel-hulled ship. The removal gives the San Antonio class a much more traditional appearance compared to its predecessors.

The transitional ships also feature a simplified bow, open side bays for small boats on the starboard side, and a truncated gate over the well deck at the stern that is open at the top when closed. The original San Antonio class stern gate is two-part design with an upper section that folds down to completely seal the well deck. The San Antonios use their well decks to launch and recover hovercrafts and other landing craft, as well as small boats. They could also use this space to deploy and retrieve large uncrewed underwater vehicles in the future.

Not all of the features from the transitional ships look set to carry over to full Flight II configuration. For instance, renderings of future ships in that subclass noticeable lack the large open bay on the starboard side, as can be seen below.

The Flight II ships are expected to differ even more than from the original Flight Is than Fort Lauderdale and McCool, including having a larger overall hull size. There will also be alterations to the stern flight deck and hangar doors. Altogether, there are “roughly 200 changes from the prior flight” in total, according to a 2022 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Overall, the Flight II San Antonio design represents a significant step back from the Flight I with its low observable (stealthy) features. This is similar in some broad respects to the evolution in the configuration of the Navy’s trio of Zumwalt class stealth destroyers. This all points to service backing away from stealth a top priority in future ship designs, especially in order to save money.

Ship designs can, of course, change significantly over the course of their lifetimes. The islands on some of the Navy’s Nimitz class aircraft carriers are quite different today than they were when those ships first entered service. More recently, one of the service’s Arleigh Burke class destroyers emerged with a radically new look following the integration of an improved electronic warfare suite.

In 2015, the Navy formally settled on the Flight II San Antonio design as the replacement for its eight Whidbey Island and four Harpers Ferry class amphibious warfare ships. This was culmination of a Navy effort that was first known first as LSD(X) and then as LX(R). The Whidbey Island and four Harpers Ferry class ships are very similar in form and function. Two Whidbey Islands have already been decommissioned since the Navy made its final decision on LX(R).

Choosing a larger, but simplified derivative of the San Antonio class rather than an all-new design, or at least one not already in Navy inventory, was intended to help keep costs low. In 2019, HII received a $1.47 billion fixed price incentive contract from the Navy for the future USS Harrisburg. In 2018, the cost to build USS Portland, the last of the true Flight I San Antonios, was pegged at around $1.6 billion, or approximately $1.98 billion when adjusted for inflation at the time writing.

However, the price point for the Flight II ships has risen in the past few years, in part due to a host of economic factors driven by multiple global crises.

“The cost of that ship [the Flight II San Antonio] had gone from $1.47 billion to the second ship at $1.5 [billion]. The third one that we’re contracting for right now is probably going to be between $1.9 and $2 billion,” now-retired Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Gilday said last March, according to USNI News. “So that increase will be somewhere between 21 and 25 percent. The FY-[25] ship, unless we did a bundle buy, would likely be a $2 billion or above – at least a 25 percent increase. We’re moving in the wrong direction.”

Last year, as part of the rollout of its annual budget request, the Navy had announced it was halting plans to buy any more Flight II San Antonios for at least five years. This was also part of a larger “strategic pause” in the acquisition of large amphibious warfare ships. This all prompted an unusually public spat between the service and the U.S. Marine Corps, which you can read more about here.

As of at least August 2023, the Navy said it had not changed its stance on the strategic pause, according to USNI News. This was despite the most recent public long-term shipbuilding plan showing a renewed commitment to acquiring more large amphibious warships in the future. The service is exploring the possibility that the cost of future San Antonio class ships could be brought down through block buy contracts for multiple ships at once.

In the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for Fiscal Year 2024, Congress did also include a provision that says “amounts authorized to be appropriated by this Act or otherwise made available for the Navy for Shipbuilding and Conversion for any of fiscal years 2023 through 2025 may be used by the Secretary of the Navy to enter into an incrementally funded contract for the advance procurement and construction of a San Antonio-class amphibious ship.” President Joe Biden signed that bill into law last December.

The Navy is still slated to get at least three Flight II San Antonios in the coming years. The hope is that the first of these, the future USS Harrisburg, will be launched later this year and delivered sometime in 2025.

In the meantime, we already have a good idea of what those ships will look like after seeing the nearly completed McCool with its new radar and other changes.

Special thanks to The War Zone reader John Stout for bringing the new pictures of the future USS Richard M. McCool Jr. to our attention.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com