The construction of the first Polar Security Cutter (PSC) heavy icebreaker for the U.S. Coast Guard is now formally proceeding. Though the milestone is important, it also underscores the PSC program’s already massive delays. The first of these new icebreakers was originally supposed to have been delivered this year and now may not arrive until 2029. The Coast Guard is sorely in need of more heavy icebreakers, with only one such ship, which is aging and increasingly hard to maintain, in its current fleet.

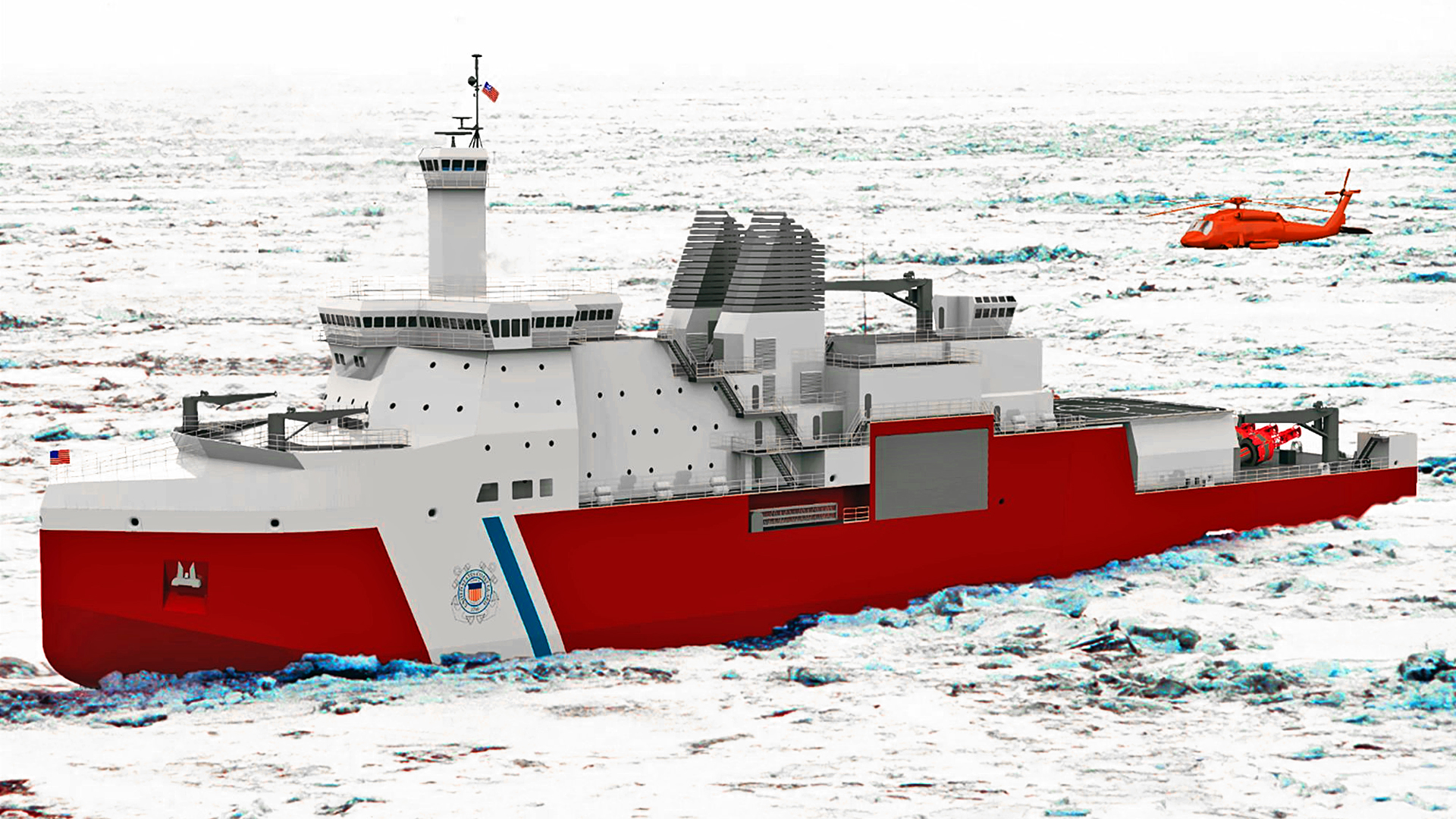

The Integrated Program Office for the PSC, which the Coast Guard runs together with the U.S. Navy, received approval to proceed with building the first PSC on Dec. 19, according to a press release yesterday. Bollinger Mississippi Shipbuilding in Pascagoula, Mississippi, is the current prime contractor for the new icebreakers. VT Halter Marine was originally hired to design and build three of the ships in 2019. Bollinger acquired VT Halter Marine in 2022.

“This decision continues work that has been underway since the summer of 2023 as part of an innovative approach to shorten the delivery timeline of these critical national assets,” yesterday’s Coast Guard release states. “The approval incorporates eight prototype fabrication assessment units (PFAUs) that are currently underway or planned.”

“The PFAU effort was structured as a progressive crawl-walk-run approach to help the shipbuilder strengthen skills across the workforce and refine construction methods before full-rate production begins,” the release adds. “The PFAU process has prepared the government and the shipbuilder to begin full-scale production of the PSC class, resulting in more precise, cost-effective, and reliable construction processes. “

“The progressive crawl-walk-run approach consists of verifying the processes utilized during the build to ensure design completeness. This includes unit readiness reviews, ensuring engineering, computer-aided design systems accurately transfer numerical control data to automated production machinery and slowing down early prototype module build times to maximize learning and enable improvements in the downstream production, engineering, and planning processes,” the Coast Guard had also said last year when the PFAU work began. “Each module requires approximately four months of labor, during which time the shipyard will continue recruiting and training additional members of the workforce to manage the transition to production of the lead hull as the prototype modules are completed.”

As already noted, the Coast Guard currently has one heavy icebreaker in service, the USCGC Polar Star, which displaces some 13,840 tons with a full load. The PSCs are expected to be substantially larger, displacing around 17,690 tons. Heavy icebreakers, in general, are “defined as ships that have icebreaking capability of 6 feet of ice continuously at 3 knots, and can back and ram through at least 20 feet of ice,” according to a report from the National Research Council of the National Academies.

The PSCs will also be much more modern and otherwise capable vessels than the Polar Star. The latter ship was commissioned in 1976 and has become increasingly problematic to operate despite a multi-phase service life extension program (SLEP). Given its age, just sourcing parts for Polar Star can be troublesome and its sister ship USCGC Polar Sea was sidelined decades ago and cannibalized for spares.

The trio of PSCs will be a welcome boost to the Coast Guard’s overall icebreaking fleets, as well. Beyond Polar Star, the service has a lone medium icebreaker, the USCGC Healy, which was commissioned in 1999.

Having just two ocean-going icebreakers presents obvious operational limits and increases the risks of capacity gaps, as was underscored just earlier this year. Healy suffered a fire that cut its planned deployment short in July. At that time, Polar Star was undergoing phase four of its SLEP. This meant the Coast Guard had no medium or heavy icebreaking capacity at all until Polar Star returned to its home port in August. Healy has also since returned to service and wrapped up a 73-day Arctic deployment on Dec. 12.

The question now is when the new PSCs will actually enter service. The mention of the “innovative approach to shorten the delivery timeline” in the Coast Guard’s press release yesterday reflects the substantial delays the program has suffered to date. As mentioned, the lead ship was originally supposed to have been delivered this year. The second and third PSCs would then follow in 2026 and 2027. The schedule slips have been blamed in the past primarily on problems in finalizing the core design. As it stands now, the initial example may not arrive until 2029, a decade after the initial contract award. Concerns are growing about potential cost overruns, as well. There are additional plans to eventually acquire new Arctic Security Cutter (ASC) medium icebreakers, but that effort has yet to begin in earnest.

The Coast Guard has acquired an additional existing ocean-going icebreaker, the Aiviq, off the commercial market. However, it’s unclear when that ship will enter operational service as it still requires unspecified “minimal modifications” to meet the requirements for its new U.S. government role. The vessel will be homeported in Juneau, Alaska, and renamed Storis, in honor of a previous Coast Guard light icebreaker of the same name with an impressive service career spanning from 1942 until 2007. At the time of its decommissioning, the previous USCGC Storis was the oldest operational ship in Coast Guard inventory.

Though a welcome addition, the new Storis will offer an at best limited capacity boost. The Coast Guard itself declared that it “requires a fleet of eight to nine polar icebreakers to meet operational needs in polar regions,” according to a separate press release yesterday about it taking formal ownership of what is still currently named the Aiviq.

Earlier this year, the U.S. government announced a new Icebreaker Collaboration Effort, or ICE Pact, intended to further boost icebreaker capacity in cooperation with NATO allies Canada and Finland. Part of the ICE Pact includes taking steps to increase the icebreaker production capacity to support the needs of friendly nations.

“If we’re trying to build a long-term order book to create the demand signal we need to have the investment that’s required to generate scale,” a senior U.S. official told reporters around the rollout of the ICE Pact back in July. “What we’re trying to do is to leverage the global order book. And our sense is if we look at allied nations that are trying to purchase icebreakers over the next decade, it’s 70 to 90 vessels.”

All of this comes as the strategic significance of the Artic only continues to grow. Receding ice as a result of global climate change has opened up new access to natural resources, from oil and natural gas to fishing, as well as trade routes. New opportunities for potentially violent global competition have emerged as a result. For years now already, the Russian military has been expanding its ability to project air and naval power into the high north, and the Chinese government has made clear it has ambitions in the region as well. Russia also has the largest icebreaker fleet in the world by far, including nuclear-powered and combat-capable types.

Finally moving ahead with the construction of the first PSC is an important development for the Coast Guard, but one that also unfortunately highlights the serious continued lag in acquiring these critical ships.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com