The U.S. Navy hopes to have a prototype high-power microwave directed energy weapon ready for shipboard testing by the end of 2026. The service sees weapons of this type as critical additional defensive options that will help its warships keep higher-end surface-to-air missiles in reserve for threats they might be better optimized for, including anti-ship ballistic missiles. The experience of American warships shooting down Houthi missiles and drones over the past six months has rammed home concerns about the magazine depth of the Navy’s surface fleets, issues The War Zone previously explored in detail in a feature you can find here.

Details about the Navy’s current high-power microwave (HPM) shipboard defense plans are included in its budget request for the 2025 Fiscal Year, which the service rolled out earlier this month. USNI News was the first to report on aspects of the Navy’s HPM plans from the new budget proposal.

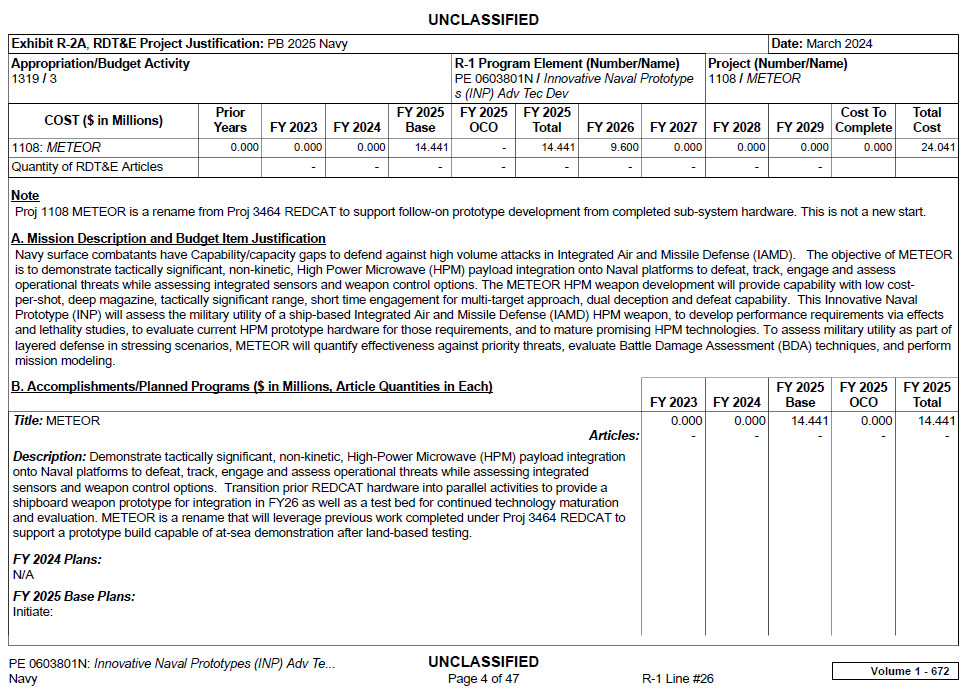

The Navy has working toward a prototype HPM weapon system specifically for this role through a program called REDCAT since at least 2023. The service’s latest budget proposal says the plan is now to rename that development effort METEOR, for reasons that are not entirely clear and that we come back to later. REDCAT and METEOR both appear to be acronyms, but their meanings are unknown.

HPM weapons, in general, are designed to generate bursts of microwave energy that are capable of disrupting or destroying the electronics inside a target system. In a maritime context, HPM systems, as they are understood now, are best suited to providing close-in defense against missiles, drones, and small boats.

A key benefit of HPM systems, which exist in other forms, compared to much more commonly discussed laser directed energy weapons is the former’s ability to produce very different graduated effects. This means a single HPM weapon could potentially offer a range of capabilities, including jamming-like functionality and more destructive effects. The wider beam that some HPM systems can emit also out gives them distinct advantages compared to lasers when it comes to their ability to engage multiple targets far faster. In certain cases, this could make them better suited to tackling drone swarms.

HPM also occupies just one end of a broader spectrum of microwave directed energy weapons. The U.S. military has even fielded lower-power microwave systems in the past on a limited (and controversial) basis as non-lethal crowd control assets.

Regardless of specific type and design, directed energy weapons are attractive because of their low cost per-shot and lack of need for any kind of physical reloading compared to traditional weapons systems involving guns or missiles. An HPM or laser weapon system has theoretically unlimited magazine depth, at least in a physical sense, although there may be limitations as to how fast they can re-emit and for how long over a given period of time. Reductions in range and general effectiveness due to atmospheric and meteorological interference is another factor. For HPM weapons, electromagnetic shielding countermeasures can be an issue, but this would add weight and complexity to the threat system. For lasers, even reflective coatings can potentially impact their efficacy under certain circumstances. As such, these systems are best utilized as part of a multi-layered defense.

With all this in mind, the Navy says “the METEOR HPM weapon development will provide capability with low cost-per-shot, deep magazine, tactically significant range, short time engagement for multi-target approach, dual deception and defeat capability,” according to the service’s 2025 Fiscal Year budget request. “The objective of METEOR is to demonstrate [a] tactically significant, non-kinetic, High Power Microwave (HPM) payload integration onto Naval platforms to defeat, track, engage and assess operational threats while assessing integrated sensors and weapon control options.”

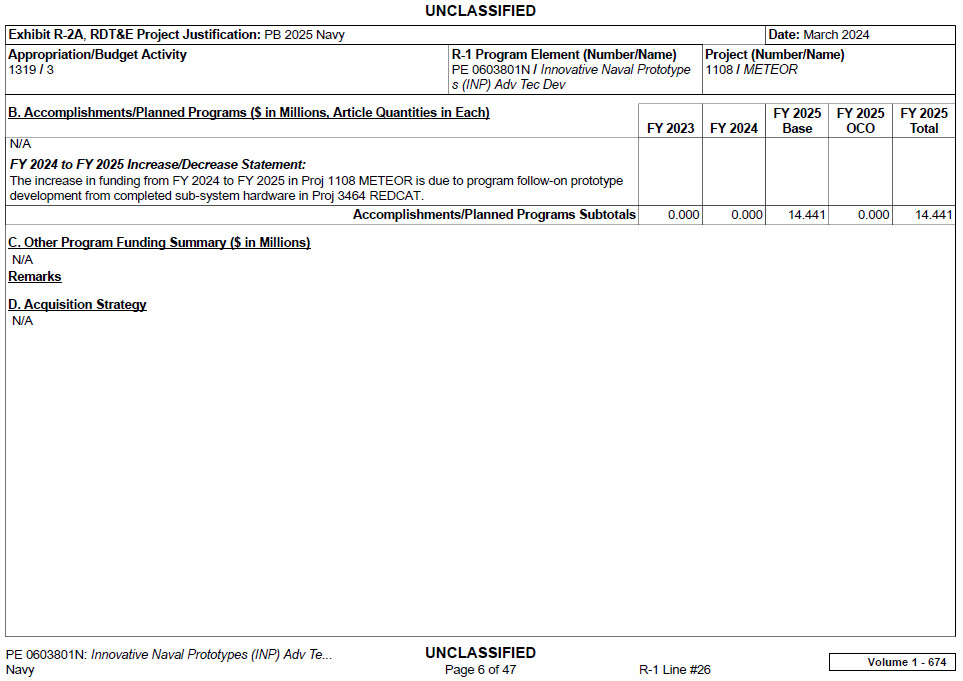

The Navy is seeking just over $9 million for METEOR in Fiscal Year 2025. This is a decrease from the $13.5 million the service asked for to support the previous REDCAT effort in the 2024 Fiscal year.

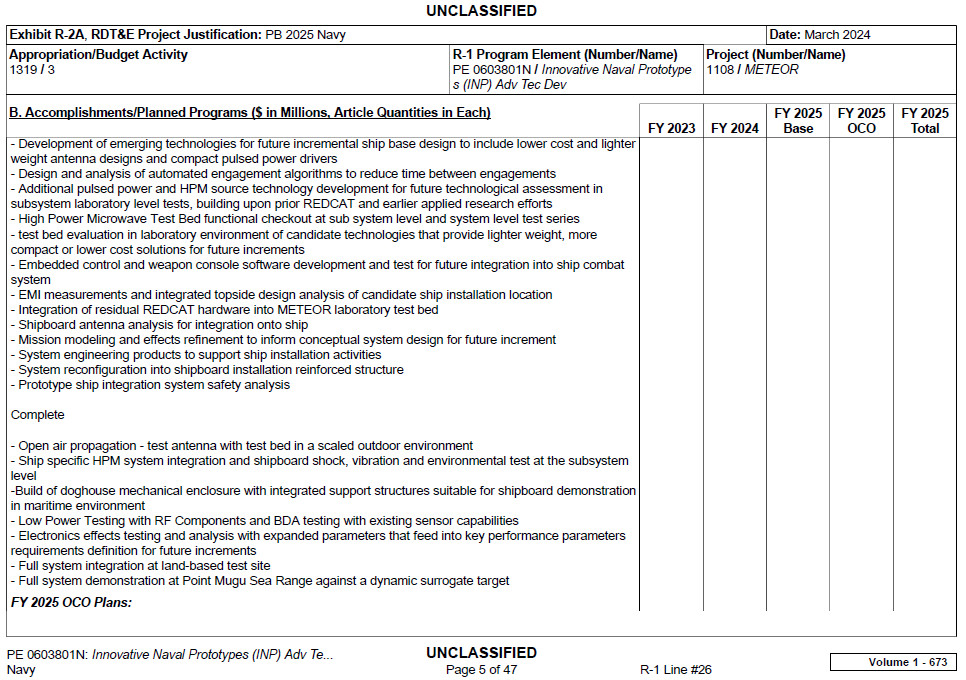

The Navy’s budget documents say that this is in part “due to a large portions [sic] of [the REDCAT] hardware build [being] completed and moving into the testing phase.” One of METEOR’s main objectives now is to “transition prior REDCAT hardware into parallel activities to provide a shipboard weapon prototype for integration in FY26, as well as a test bed for continued technology maturation and evaluation,” those documents add. Land-based testing of the system is also expected to occur first.

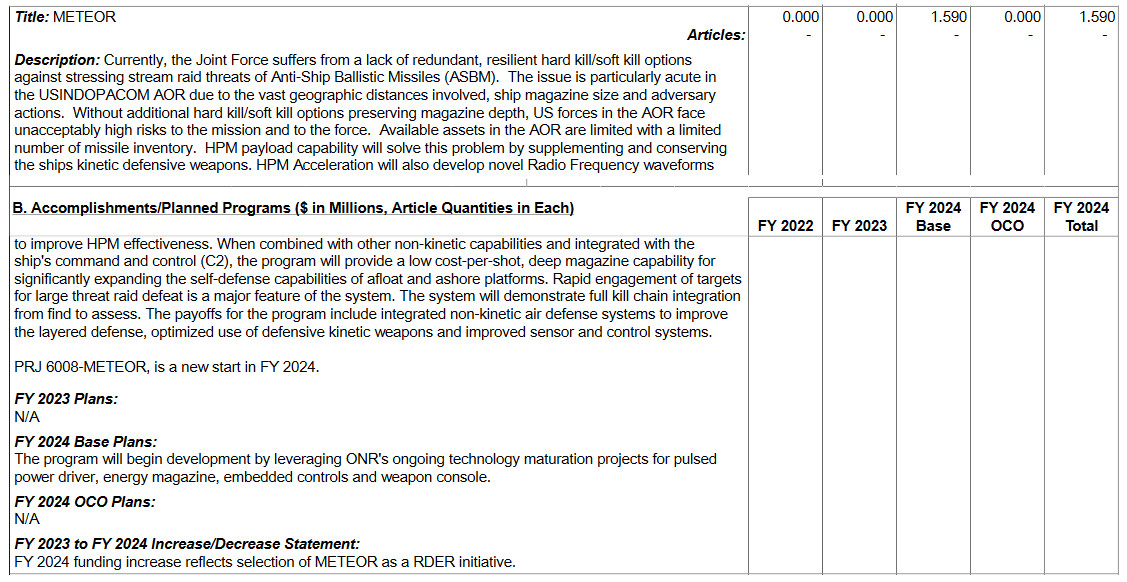

METEOR also looks to have been included in a separate section of the Navy’s previous 2024 Fiscal Year budget request for programs being conducted as part of the Pentagon’s Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve (RDER) initiative. Whether or not the Navy is seeking additional funding for this HPM development effort through that part of the budget in the 2025 Fiscal Year is unclear. The service’s latest budget proposal does not include specific details about the programs contained within that line item.

The METEOR entry in the Navy’s proposed 2024 Fiscal Year budget provides interesting additional context about the Navy’s desire for shipboard HPM defense capability.

“Currently, the Joint Force suffers from a lack of redundant, resilient hard kill/soft kill options against stressing stream raid threats of Anti-Ship Ballistic Missiles (ASBM). The issue is particularly acute in the USINDOPACOM AOR [U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Area of Responsibility] due to the vast geographic distances involved, ship magazine size and adversary actions,” the service’s Fiscal Year 2024 budget request explains. “Without additional hard kill/soft kill options preserving magazine depth, US forces in the AOR face unacceptably high risks to the mission and to the force. Available assets in the AOR are limited with a limited number of missile inventory. HPM payload capability will solve this problem by supplementing and conserving the ships [sic] kinetic defensive weapons.”

This is a clear reference to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) very open development and fielding of an increasingly capable and diverse array of ground, sea, and air-launched anti-ship ballistic missiles. The PLA’s efforts are part of a larger anti-access/area denial strategy that is heavily focused on denying U.S. carrier strike groups the ability to operate within striking distance of its shores.

There have been reports that Russia may now be exploring the development of similar capabilities, which it could also deploy in the Pacific region. The U.S. Army is also now pursuing anti-ship ballistic missiles of its own.

Iran has also emerged as a major developer of anti-ship ballistic missile capabilities and a key source for their increasing proliferation, including to non-state actors. Iranian-backed Houthi militants in Yemen have now become the first to employ these weapons in anger and how shown just how real a threat they pose in the course of their ongoing anti-ship campaign in and around the Red Sea. U.S. authorities say that the Houthis used anti-ship ballistic missiles in the attack that ultimately led to the sinking of the Belize-flagged cargo vessel MV Rubymar in February and the fatal attack on the Barbados-flagged container ship True Confidence earlier this month.

The Houthis have also been using anti-ship cruise missiles, aerial kamikaze drones, and explosive-laden uncrewed surface vessels and underwater vehicles (USVs and UUVs) – the exact kinds of threats an HPM weapon would be most useful against – to target foreign warships and commercial vessels off the southern coasts of the Arabian Peninsula. The Yemeni militants have also launched complex attacks involving multiple types of missiles and drones.

All of this only further underscores the Navy’s stated reasoning behind the Meteor HPM program, even if those weapons are not primarily intended to be used against ballistic missile threats. That being said, there is a possibility that HPM systems could have some limited use against lower-tier anti-ship ballistic missiles.

Regardless, Navy warships have particularly limited and costly options for engaging ballistic missile threats, which present unique challenges for defenders just owning the very high speeds they reach during the terminal phase of flight. Advanced designs with varying degrees of maneuverability can be even harder to track and intercept. Novel hypersonic weapons, another set of emerging threats, combine these attributes to be even more difficult to protect against.

One of the Navy’s main weapons for tackling ballistic, as well as hypersonic threats, to its ships today are variants of the Standard Missile 6 (SM-6). This is a highly capable multi-purpose design that can also be used against a variety of other targets in the air and on the surface, but one that is also expensive. In the surface attack role, SM-6 functions in many ways like a ballistic missile. The Navy’s 2025 Fiscal Year budget request puts the unit price of an SM-6 Block IA, the most advanced variant currently in production, at $4.2 million. Each one of the still-in-development Block IB version, which will have greatly improved performance and other capabilities, is expected to have a price tag of around $8.5 million.

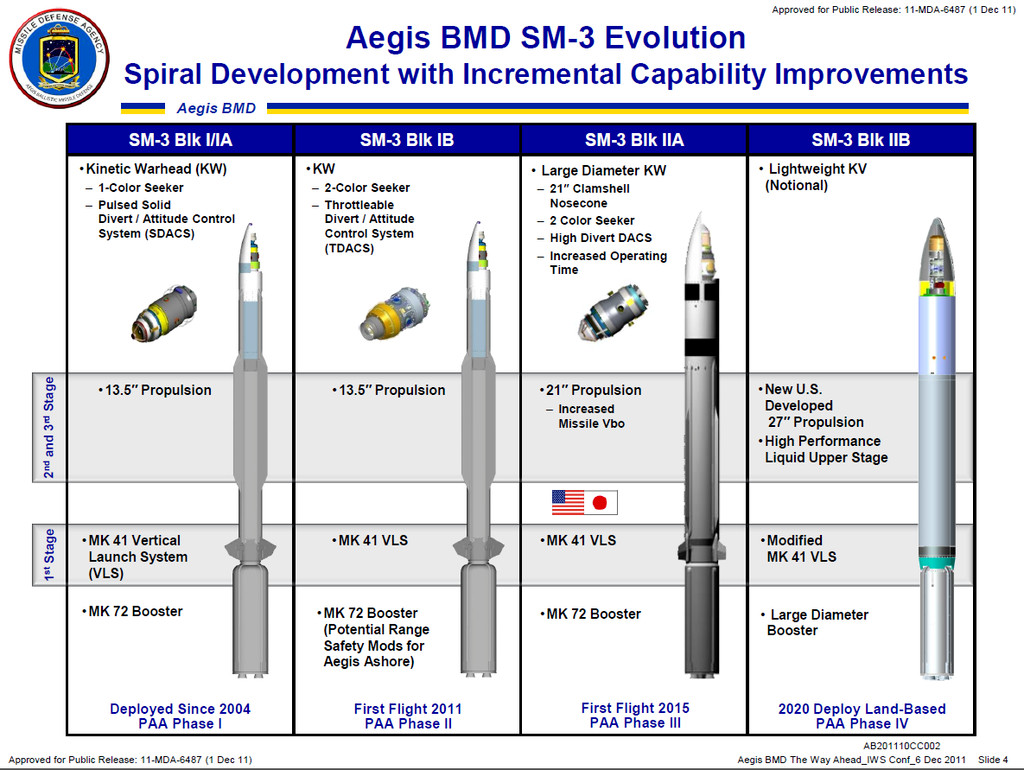

A portion of the Navy’s Arleigh Burke class destroyers and the service’s dwindling number of Ticonderoga class cruisers are also capable of employing variants of the SM-3. The members of the SM-3 family are specifically designed to intercept higher-end ballistic missiles, including intercontinental ballistic missiles (IBCM), in the mid-course portion of their flight outside of the Earth’s atmosphere. The SM-3 Block IIA, the most advanced variant in production, has a unit cost of around $28 million, according to Pentagon budget documents.

The current price of a single Block IIIC variant of the SM-2, the latest version of the Navy’s current standard ship-launched medium-range surface-to-air missile, is also around $2.5 million. Shorter-range RIM-162 Evolved Sea Sparrow Missiles (ESSM), each of which costs some $1.5 million, are another important component of the service’s existing shipboard air and missile defense arsenal.

Navy ships can only carry so many of these missiles at once in their Vertical Launch Systems (VLS) and currently the service has no operational capacity to reload VLS cells at sea. This has long raised concerns about how quickly individual ships might deplete their magazines in a major conflict, as The War Zone explored in detail in our recent feature.

Just in operations against the Houthis between October and February, Navy warships fired at least 100 Standard series missiles. Expenditures of these and other weapons have only continued since then. The service could expect to see even higher volumes of incoming threats, including more capable anti-ship ballistic missiles, in any potential high-end fight against China in the Pacific.

“We are a learning organization. And so as we apply the concepts of defense in depth, it isn’t always an expensive SM-2 missile that gets shot at a UAS [uncrewed aerial system],” Navy Adm. Christopher Grady, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said at a press conference about the proposed 2025 Fiscal Year budget earlier this month. “We’ve learned how to use other systems and have rapidly adjusted to this concept of defense in depth. And that’s what gives me great confidence that we’ll be able to sustain that as long as it takes to change the calculus over there.”

The Navy’s attitude toward the anti-ship ballistic missile threat, specifically, has dramatically shifted in recent years. In 2021, now-retired Navy Vice Admiral Jeffrey Trussler, then the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Information Warfare, said “I hope they [the Chinese] just keep pouring money into that type of thing,” indicating that the service felt at the time it had sufficient countermeasures and/or tactics, techniques, and procedures in place to defend against them. This assessment has clearly changed since then.

When operational Meteor HPM weapons might start being integrated onto Navy ships remains to be seen. The service could also seek to field systems, even on a limited basis, before 2026 through other programs. In February, Naval Sea Systems (NAVSEA) put out a very broad call for potential counter-drone capabilities that could be added to its ships within 12 months of a contract award.

As already noted, HPM systems are not new and a number of potentially viable designs already exist in various stages of development within the U.S. military and the commercial sector. Private firm Epirus has previously shown a concept for a shipboard version of its Leonidas HPM system, seen at the top of this story, that leverages existing components of the Mk 15 Phalanx Close-in Weapon System (CIWS) that is found on many Navy warships. BAE Systems has presented an HPM weapon concept for use in the maritime domain in the past, too.

The Navy has already been fielding various tiers of laser directed energy weapons on a limited number of warships and is in the process of developing additional designs that could be deployed on a broader basis.

No matter what, the Navy clearly sees HPM weapons as a key part of future layered defense arrangements for its warships to help ensure that they can maximize their overall defensive capabilities to protect against an array of threats, including anti-ship ballistic missiles.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com