A government watchdog report released Tuesday highlights problems in the U.S. Navy’s yearslong, multi-billion dollar Ticonderoga class cruiser modernization program. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) report sheds new light on the systemic issues that have plagued the effort, such as lax contractor oversight and a lack of understanding regarding what kind of work the ships would need before they could return to the fleet.

At the same time, the GAO report highlights the corrosive effect of deferred maintenance and warns that the Navy hasn’t sufficiently codified reforms to prevent such a boondoggle from happening again, particularly as it embarks on an ambitious $10 billion modernization program for 23 ships in its Arleigh Burke class destroyer fleet.

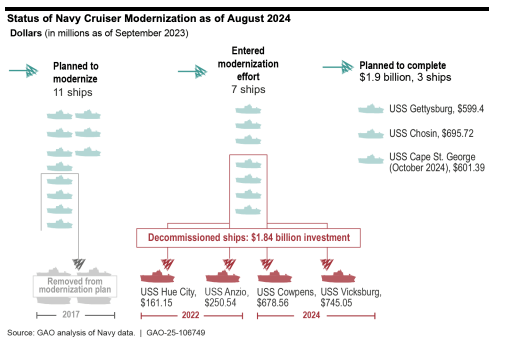

The U.S. Navy spent nearly $4 billion modernizing seven of its aging Ticonderogas over the past decade, according to the GAO. But only three of the large surface combatants will complete the modernization process, and none of those will gain an extra five years of service life as originally envisioned. Nearly half that money spent, $1.84 billion, was “wasted” modernizing four cruisers that never returned to sea and were retired by the Navy.

For the cost and relatively short extra service life of its three modernized cruisers, the service could have nearly bought two brand-new destroyers.

“While it is too late to salvage the cruiser modernization effort, failure to learn critical lessons poses risk to the future of the Navy’s surface fleet as it begins significant modernization efforts for other ship classes,” the report states. “This is particularly true for DDG Modernization 2.0 and the amphibious ship service life extension and modernization. While some issues were unique to the cruiser effort, we observed shortfalls that span across the planning and execution of Navy ship maintenance and modernization periods.”

The Ticonderogas carry Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAM) and serve as air and defense batteries and command and control platforms. They are also equipped with Harpoon anti-ship missiles and MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopters, and execute anti-submarine warfare operations. They were built in the 1980s and early 1990s and act as the central node in the carrier strike group’s air and missile defense architecture, with their unique capacity to host the air defense commander of the strike group.

There are nine cruisers still serving in the Navy today. Six are slated to be decommissioned in the coming years, while the other three —USS Gettysburg (CG-64), USS Chosin (CG-65) and USS Cape St. George (CG-71) — have been modernized or are close to finishing modernization and will serve out toward the end of the decade.

As TWZ reported last month, modernization has included Aegis Combat System improvements, a new AN/SPQ-9B radar and upgrades to the existing AN/SPY-1B, as well as an updated SQQ-89A(V)15 sonar suite, Mk 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) modifications, and other work.

Gettysburg entered the Middle Eastern waters of U.S. Central Command this week along with the rest of the USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) carrier strike group, where it will perform air defense functions in a region that has been plagued by Iranian-backed Houthi rebel missile and drone attacks for the past year.

Chosin completed modernization and sea trials in early 2024, and the Navy plans to deploy it once more before its planned retirement in Fiscal 2027. Work on Cape St. George continues, with the Navy planning sea trials for this fiscal year, which began Oct. 1.

“Like USS Gettysburg and USS Chosin, the Navy currently plans to deploy USS Cape St. George at least once before divesting the ship in fiscal year 2027, according to senior Navy officials,” the report states, adding that the Navy now plans to decommission all three ships by Fiscal 2030.

The Navy has been working to have Flight III Arleigh Burke class destroyers take on the air defense command role of cruisers, but to date, the service only has one Flight III destroyer, and questions have been raised about the viability of having a “maxed out” subclass of destroyers serving in such a capacity, TWZ previously reported. The GAO notes that the new Flight IIIs are facing “significant delivery delays,” with some ships falling more than two years behind schedule.

TWZ has covered the fits and starts of the Navy’s cruiser modernization program, and Tuesday’s GAO report highlights the broader systemic failings that led to it. The Navy plans to divest its three modernized cruisers “without fully assessing the implications to its force structure, including costs, benefits and risks,” according to the GAO, and the service will look to squeeze one more deployment out of those three ships before they are mothballed.

But that decision, according to the GAO, “is not based on the full knowledge of the condition of the ships and associated operational implications because the Navy has not completed a comprehensive assessment of costs, benefits and risks of divesting the ships, as well as of ship conditions.”

Navy officials told the GAO that “they do not see the value the cruisers bring to the fleet,” because they are unreliable and suffer longstanding issues such as hull cracking, while also being less capable in some regards than more modern destroyers. But those same officials also acknowledged that they have not conducted inspections to understand the reliability and condition of the modernized ships.

Cruiser modernization dates back to 2012, when the Navy first sought to retire multiple Ticonderogas due to budget constraints. Congress rejected such proposals and funded the modernization effort, and the sea service planned a phased approach that would give 11 cruisers five years of extra service life each.

But the Navy did not fully understand the condition of its cruisers before they entered modernization, and officials told GAO that the ships were in worse condition than they realized. This was due to the Navy cancelling maintenance periods for their ships earlier in their service lives, allowing problems like fuel tank cracks to fester and balloon into major problems by the time modernization commenced.

“For example, according to OPNAV officials, the Navy deferred cruiser maintenance periods during the 2000s due to the operational need for the cruisers during the Global War on Terror,” the report states. “Then, Navy officials told us the Navy canceled maintenance periods for the cruisers between 2011 and 2014, because the Navy was planning to divest the cruisers.”

The Navy tried to better understand the cruisers’ conditions after Congress funded the modernization, and while these surveys were “comprehensive and robust,” the high volume of unplanned work that emerged “indicates that these efforts to gain information were unable to make up for years of not tracking ship condition and deferring maintenance,” the GAO report states.

Officials told the GAO that the service is getting better at tracking required maintenance, helping ensure that ships can meet their service lives.

“However, these improvements are more impactful as a preventive measure on newer ships that have yet to fall behind than for older ships where the Navy has already deferred significant maintenance and lost track of condition, as happened with the cruisers,” the report states.

Under its so-called “Phased Modernization Plan,” the Navy inactivated the seven cruisers and cut manning from 350 billets to a 45-sailor caretaker crew, to save costs. Midway through each cruiser’s modernization, the ship’s force was supposed to be brought back to a normal size to help reactivate the ship, a decision the GAO called “unusual.”

“A ship going through maintenance or modernization typically would not have its crew significantly reduced or be inactivated, according to Navy officials,” the GAO report states. This led to a host of problems when it came time to turn a given cruiser back on.

“Inactivating the ships and reducing the crew made it more difficult for program officials to understand the condition of and maintain the ships, thus inhibiting accurate planning for the modernization effort,” according to the GAO. “For example, according to Navy officials, it was hard to assess the condition of inactivated ship systems. Further, because the ships had reduced crews of 45 sailors and the systems were turned off, these systems further deteriorated.”

The GAO’s report — which involved interviewing more than 100 officials — also found that the Navy “did not effectively plan the cruiser effort,” leading to a high amount of unplanned work that resulted in schedule delays and cost growth, including 9,000 contract changes.

“The Navy has yet to identify the root causes of unplanned work or develop and codify root cause mitigation strategies to prevent poor planning from similarly affecting future surface ship modernization efforts,” the report states.

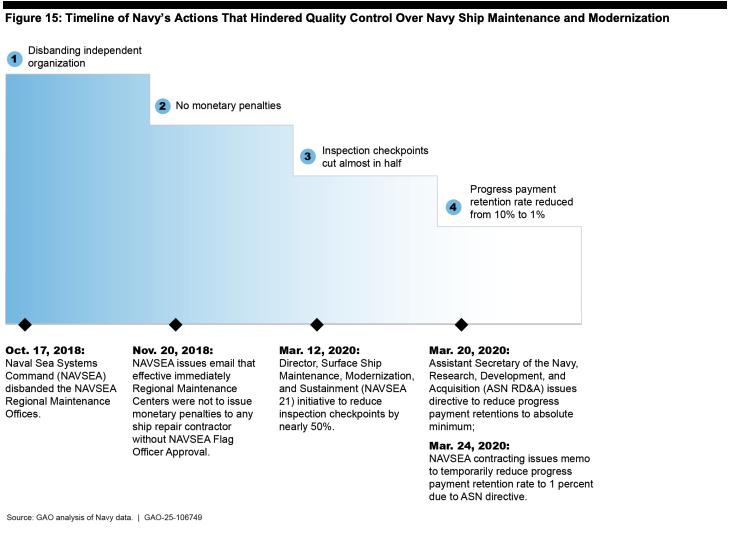

Once work began on the cruisers, the Navy at times struggled to provide the proper level of oversight, the GAO report states. A 2018 decision “restricted officials from assessing monetary penalties to contractors without senior leadership approval,” according to the GAO. And in 2020, leadership reduced inspections of contractor work by nearly 50%, actions taken “to maintain strong working relationships with the contractors because of the Navy’s dependence on them to modernize its fleet.”

“Despite widespread instances of poor-quality work during the cruiser modernization effort, [Naval Sea Systems Command] senior leadership discouraged [Regional Maintenance Centers] and contracting officials from fully using key quality assurance tools to maintain the industrial base and a positive working relationship with the ship repair industry,” the report states. “This reduced the RMC’s ability to ensure that contractors were producing quality work. Further, Navy guidance does not set forth clear roles that enable coordination among several key stakeholders within the Navy, which further inhibited effective oversight of work.”

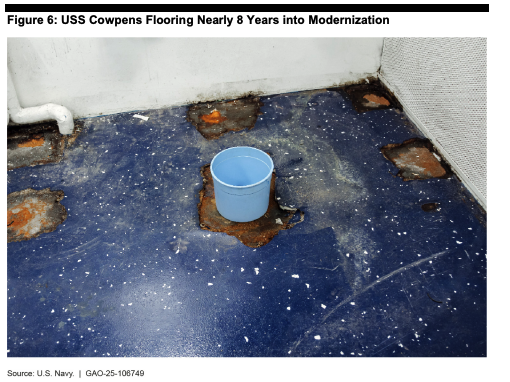

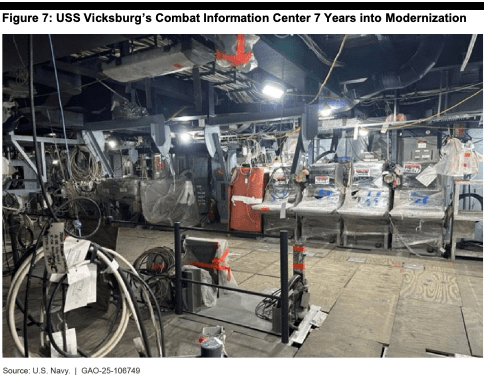

The GAO highlights several ships in the dwindling cruiser fleet and their persistently subpar state, even after years of modernization work.

The USS Cowpens (CG-64), decommissioned in August 2024, went through eight years of modernization and still needed roughly $88 million and three more years of work as of June 2022, according to GAO, and photos from the following year reveal rust and corrosion on the deck plate, as well as holes in its flooring.

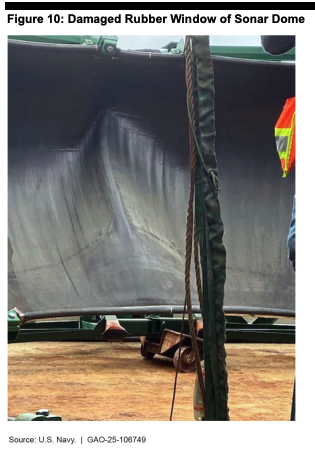

Another, USS Vicksburg (CG-69), was decommissioned in July 2024. Officials estimated in 2023 that it would require an additional $100 million, which did not include the cost to dry dock the ship and fix its sonar dome.

Even cruisers that have completed modernization are having issues, according to the GAO. The deployed Gettysburg completed its modernization and sea trials in February 2023, and the Navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey ruled that the ship met the minimum standard for going to sea. But a year later, in January 2024, the same board identified “several outstanding issues during an inspection of the ship’s condition.”

“For example, several elements of the weapons systems were inoperable or degraded and there were structural issues throughout the ship,” the report states.

The Navy addressed several of these issues after that inspection, and the cruiser completed 18 days at sea in June 2024, including a successful missile launch and intercept using its updated combat systems software.

But before Gettysburg deployed in September 2024, the ships force told GAO of problems with steering gear and hydraulic power unit parts, among others, and that the Navy cannibalized parts from already-decommissioned cruisers.

“According to the ship’s crew, propulsion plant and electric system failures were key concerns for the USS Gettysburg deployment,” the report states.

Cruisers that entered modernization all suffered “widespread contractor performance and quality issues,” with Navy Regional Maintenance Centers issuing 1,400 corrective action requests to contractors to fix their incorrect work, the report states.

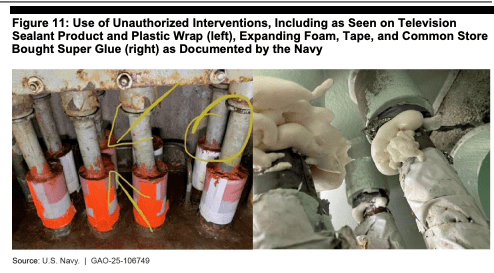

One contractor used “unauthorized materials such as plastic wrap, tape with common store bought glue, expanding foam and and as seen on television sealant products” to fix large sonar dome cables on a cruiser not identified by name in the GAO report.

In another instance, contractors installed gun foundations at an incorrect height, requiring them to be removed and reinstalled, which led to a four-month delay.

“In addition, the gun could not fire without hydraulic fuel leaking,” the report states. “Ship’s crew officials told us that they did not discover this issue until combat systems sea trials. The Navy has since corrected these issues.”

On another ship, quality assurance officials noted five contractor personnel in three separate areas of the ship using incorrect welding methods in a single day.

The Navy also failed to ensure that contractor work was sequenced properly. This led to delays in contractors installing equipment, and incomplete cabling and electrical distribution, aboard Vicksburg, the ship’s crew told GAO.

“They also told us that these issues led to 22 tons of electronic equipment sitting idle with no air conditioning,” the report states. “Officials said a lack of temperature control caused problems preserving the computer equipment used to operate the Aegis Combat System aboard USS Vicksburg and that most likely a large portion of the electronic equipment is not salvageable. As another example, crew aboard USS Chosin told us that a modernization team contractor was unable to test a key system because the ship’s ventilation was not working. This caused a delay in ensuring that all key systems were operational.”

The GAO report points out how unusual it is for a ship in maintenance to be transferred from Naval Surface Forces to Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) and back, and Navy officials noted that transferring ownership should not happen again.

Navy officials concurred with the GAO that such lessons should be codified, but also told the watchdog that the Navy may need to inactivate a ship, reduce its crew size and transfer ownership to save money “in a budget constrained environment.”

“They also stated that Navy leadership needs to retain flexibility,” the report states. “However, doing so would likely significantly increase the risk of the Navy experiencing poor outcomes, as occurred with the cruiser modernization effort.”

The Navy faces other challenges to increasing its overall fleet size, as well as maintaining its current warships and submarines. The new Constellation class frigates are also mired in delays, cost growth, and other problems, which you can read more about here. This is what led the service to announce last month that it would be extending the service lives of a dozen more Flight I Arleigh Burkes into the 2030s to help maintain overall operational capacity, according to past TWZ reporting.

The Navy is relying on modernization efforts to maintain fleet size. And while service officials express confidence that the destroyer modernization program will not repeat the cruiser mistakes of the past, GAO’s findings indicate that such pitfalls remain a possibility.

Contact the author: geoff@twz.com