The U.S. Navy’s Medium Landing Ship (LSM), a platform many view as crucial to transporting Marines among remote islands in a future war against China, is dead in the water for the time being. Reports emerged this week that sea service leaders balked at high cost estimates that have come in from industry to build the vessel. The pause raises questions about how the U.S. Marine Corps will enact its West Pacific, island-hopping concepts of operations, known as Expeditionary Advance Base Operations (EABO), and it is the latest delay to afflict the program.

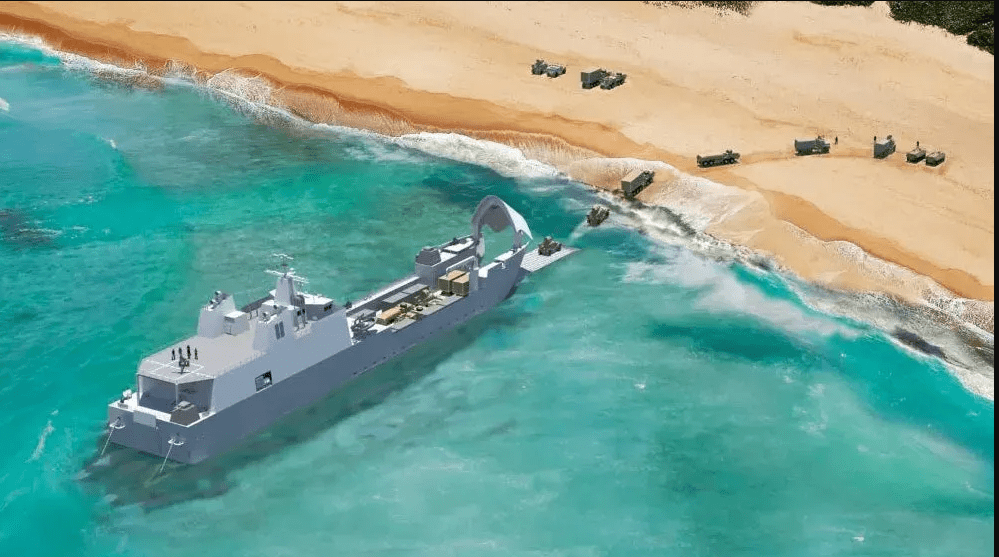

Formerly known as the Light Amphibious Warship (LAW) and also referred to as the Landing Ship Medium, the vessel is envisioned as delivering forces right onto a beach without any established port facilities. It would ferry mobile, platoon-sized Marine units to islands where they would fire anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM) at Chinese forces and collect data for the other U.S. forces, among other tasks.

Those Marines would also work to deter opponents in situations short of actual conflict, while helping to control littoral areas and seascapes. Such missions would be conducted by the new Marine Littoral Regiments (MLR). They would occur within China’s striking distance, likely in the southern Japanese islands and in the Philippines, part of a sea-denial campaign spanning the South China Sea and East China Sea, analysts say.

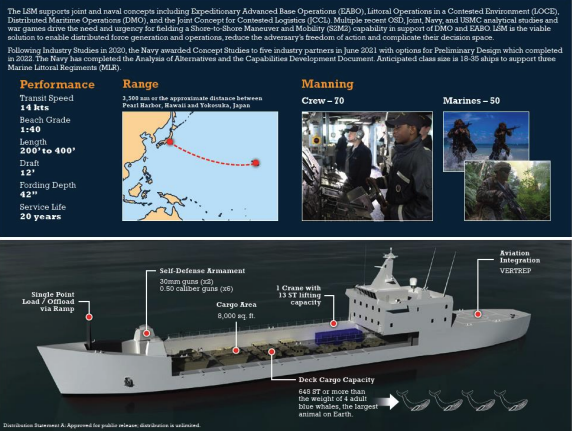

Navy and Marine Corps leaders have called for between 18 to 35 LSMs that would range in length from 200 to 400 feet, with a 12-foot draft, each crewed by about 70 sailors, according to an August Congressional Research Service (CRS) report. The LSM would provide 8,000 square feet of deck cargo space, carrying 50 Marines and nearly 650 tons of equipment.

LSM would also feature a helicopter landing pad, two 30mm guns and six .50-caliber machine guns for self defense. They would have a 14-knot transit speed, a cruising range of 3,500 nautical miles, and would be expected to serve for 20 years.

But as the Marine Corps continues to urgently relay their need for the LSM, the Navy canceled a request for proposals to build the LSM after bids from industry came in too high, according to the sea service and media reports.

Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) officials declined to tell TWZ the cost estimate that led the service to cancel its solicitation for the LSM on Dec. 6, saying it was unable to provide “source selection sensitive information.”

The LSM program is now working to revise its acquisition strategy to “address affordability concerns,” the command said.

“A Request for Information (RFI) is likely to be released to industry very early in 2025 to identify non-developmental options,” NAVSEA added.

USNI News’ Mallory Shelbourne first reported the latest LSM setback this week, citing comments by Navy leadership.

“We put it out for bid and it came back with a much higher price tag,” USNI News quoted Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition Nickolas Guertin as saying at an American Society of Naval Engineers symposium last week. “We simply weren’t able to pull it off. So we had to pull that solicitation back and drop back and punt.”

Guertin noted that the service had what they thought was a “bulletproof” cost estimate, and a “pretty well wrung out design in terms of requirements, independent cost estimates,” USNI News reported.

The Navy’s proposed Fiscal Year 2025 budget requests show the first LSM would cost $268 million, but costs would average out to roughly $156 million by the seventh and eighth ship, according to the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

A U.S. defense official speaking on condition of anonymity told TWZ Thursday that initial plans called for each ship to cost between $100 million and $150 million, but that the Navy added features to meet their requirements, and that shot the price of each ship up dramatically. The Marines wanted a ship that was less exquisite and more numerous, according to the official.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) said in April that Navy estimates for the LSM’s cost have “varied widely.” CBO’s own analysis found the LSM could cost $340 million to $430 million per ship for an 18-ship program, an estimate it said reflects the range of full-load displacements – 4,500 tons to 5,400 tons – in preliminary designs that shipbuilders submitted to the Navy.

Marine Corps representatives told TWZ Thursday that the service is currently working on “a way ahead” for the LSM program in conjunction with the Navy, and is exploring other options that will allow the MLRs to continue advancing the EABO concept.

LSMs are seen as a key mover of Marines under EABO, which is a major component of the Marine Corps overhaul known as Force Design 2030 that seeks to ready the service for a war with China. Part of that original vision saw the Navy and Marines moving away from a laser focus on large amphibious assault and landing ships. A more nimble, numerous and cost-effective fleet of small ships tailored to distributed warfare in the Pacific would offset some of the reduced large amphibious warship force. That so far has not happened, and the ‘Gator Navy’ fleet focused on massive beach landings, which many say are unrealistic in modern warfare, remains intact.

TWZ has extensively reported on EABO and what it means for the Corps:

“At its core, EABO involves relatively small groups of Marines quickly establishing bases of operation in forward areas, especially on small islands. This concept of distributed operations also envisions them being able to then rapidly reposition themselves, as necessary. The purpose is to use these flexible, responsive ground forces to help control littoral areas, and even surrounding ‘seaspaces,’ to deter opponents in situations short of an actual conflict, and then, if that fails, be well-positioned to engage enemy forces.”

In a statement to TWZ Thursday, the Marine Corps reiterated that the LSM is a critical component of the island-hopping mission it expects the MLRs to one day embark upon under the EABO concept.

“The medium landing ship (LSM) is intended to provide surface maneuver direct support to Stand-in Forces (SIF) and the Marine Regiments executing missions on behalf of the naval campaign,” the service said. “Put plainly, to move a Marine regiment around the Pacific or elsewhere, it would take many C-17s … to move the personnel and equipment that a medium landing ship can move. And that’s without the geographic flexibility of a beachable surface craft.”

The Marine Corps also told TWZ that it is working on “an acquisition way ahead” for the LSM, and that the “complex requirements” of the ship “challenge government and industry to design and produce affordable materiel solutions.”

For now, the Marines are making do and are leaning on existing commercial and military capabilities that require little modification, according to the service. Those efforts have included Marines using stern-landing ships to inform the development of the LSM in the interim. A June 2024 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report warned that “existing commercial designs require significant modifications to meet LSM’s requirements,” and that none of the commercial designs assessed by the Navy had the required beachability or cargo fuel capacity.

“Although not optimal, such vessels will provide both operational capability and a sound basis for live experimentation and refining detailed requirements for the LSM program,” the Corps said in a 2022 update to Force Design 2030.

The Marines first introduced the idea of the LSM in 2020, but the program has suffered several stalls, with plans to acquire the first vessels initially pushed back to Fiscal Year 2023 and then to Fiscal 2025, as the Navy grapples with hefty bills for submarines and other needs, Defense News reported in 2022.

The Navy began receiving LSM concepts from shipyards and design firms in late 2020. By January 2024, the Navy was seeking proposals for the LSM, with Marine Corps officials saying they were on pace to procure in 2025 and deliver in 2029, according to the CRS.

Opinions continue to differ on what the LSM should be, with the Navy wanting a survivable vessel and the Marines looking to field the capability as quickly as possible, as some warn that China could invade Taiwan and prompt a U.S. response in the next few years.

Marine Corps Commandant Gen. Eric Smith downplayed concerns about the LSM’s survivability in 2023, according to a report by Defense Daily’s Rich Abbott.

“Well, if I take that to the next step, soldiers and Marines, y’all can’t leave the barracks because the enemy’s got machine guns,” Smith was quoted as saying. “Hey, pilots, you got to stay on the tarmac because there’s anti-air missiles out there. Hey, submariners and ship drivers, y’all can’t leave the pier because there’s [anti-ship cruise missiles] and torpedoes. That doesn’t make sense.”

TWZ has reported on leaders playing down the differences between the services on where LSM should head. Despite “healthy friction” over the LSM, “there is no daylight between us” on the need for those ships, Navy Vice Adm. Scott Conn, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfighting Requirements and Capabilities, said at a conference in April 2023.

The latest LSM travails again highlight a longstanding tension between the Navy and Marine Corps. The Marines need certain maritime capabilities for amphibious operations. The Navy is tasked with moving those Marines, but must pay for the ships the Marines need. Similar debates have surfaced around the size of the larger-deck amphibious fleet in recent years as well.

The amphibious force is “not the favorite thing of the Navy to deal with,” according to Bradley Martin, a retired Navy surface warfare officer who spent two-thirds of his 30-year career at sea.

“I say this as a guy who spent a number of years on the amphibs,” said Martin, now a senior policy researcher with the RAND think tank. “The Marines aren’t very worried about how the Navy sustains ships, and the Navy hasn’t been really clear about what it takes to sustain ships. There’s been that disconnect.”

Mark Cancian, a retired Marine Corps colonel and senior advisor with the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank’s defense and security department, told TWZ Thursday that the LSM conundrum is different because, unlike past amphibious disagreements, the Marines want a low-end ship and the Navy is arguing for a high-end capability.

Cancian worked in the Pentagon in the 1990s and recalled a proposal for the equivalent to a LHA or LHD amphib built to civilian standards that could be used for peacetime presence missions. It would be cheaper but unsuitable for wartime needs.

“The Marine Corps fought against it tooth and nail,” he recalled. “I remember Marines being in my office, saying it would be immoral to put Marines on a ship built to civilian standards.”

“There’s going to be some tough negotiations between the Navy and Marine Corps,” Cancian added. “And the new administration will weigh in too, on force design, on the topline and shipbuilding. But the Marine Corps won’t give up.”

In general, the LSM’s concept has not matched its execution, Martin said.

“They need something, and this just isn’t the right capability,” he said. “It’s too expensive. When you get right down to it, you’ve got to move stuff around, even if you beach, you’re still going to be vulnerable during the period that you’re beached.”

The Pentagon should instead be investing in civilian-manned ferries for such missions that would be part of the existing strategic sealift fleet, Martin said.

China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is already at work on such a civilian-military meld. It has been modifying roll-on, roll-off (RO/RO) ferries with stern ramps that will allow the force to launch and recover amphibious combat vehicles in the event of a cross-strait invasion of Taiwan, Maritime Executive reported in 2023. Such a move would give the PLAN a big boost when it comes to the amount of amphibious lift it could summon for such a landing, allowing Beijing to close its amphibious gap without building more military amphibs.

The Pentagon’s annual report on China’s military capabilities released this week notes that “amphibious marine forces continued to conduct routine driver integration training with PLAN amphibious and civilian roll-on/roll-off (RO/RO) vessels.”

“Amphibious marine forces continued to conduct routine driver integration training with PLAN amphibious ships and civilian roll-on/roll-off (RO/RO) vessels,” the report states. “Non-amphibious marine forces continued civilian-military integration training, with a new PLANMC BDE in the northern theater observed loading vehicles onto a RO/RO and conducting a sea crossing before unloading from the RO/RO.”

China has also used civilian ferries to move its amphibious forces and launch amphibious craft during beach invasion drills. Turning commercial ships into helicopter carriers is also something China’s training to do during a major contingency operation.

The LSM also reflects problematic requirements thinking, according to Martin.

LSMs won’t be used to storm a beach, or for opposed landings, Martin said. But the requirements include a military crew, damage control and other features that don’t reflect its core mission, which drives up the price.

“Anywhere that ship might go is subject to targeting, but having the type of weapons it’s got on it won’t do much good against the type of threat the Chinese or any capable power are likely to throw against it,” he said. “It’s not a well-conceived answer.”

Real talk about what capability the Navy could provide for the Marines to carry out EABO might have occurred at lower levels, but likely got diluted further up the chain, he said.

“It got further and further away from a discussion about requirements, toward just a head nod that we’re going to do it,” Martin said. “That is a problem with the Navy’s management of requirements in general. All the services are guilty of this to a degree, but the people generating requirements are not talking to other people generating requirements, and they’re not engaged with the people actually designing equipment, and that’s a big problem.”

Even as the Marines proceed with Force Design 2030 and EABO, CRS’s August 2024 LSM report notes that debate about the merits of the two plans continue.

Questions remain about whether the concepts focus too heavily on China war scenarios at the expense of other Marine Corps missions. It also remains unclear whether the MLRs would be able to get access to the islands they need to operate from, in addition to resupply and survivability concerns. There’s also the question of whether the MLRs could contribute meaningfully to sea-denial operations, although the Marines emphasize that the MLR platoons would be collecting vital data as well.

American military brass portrays the threat of war with China as one that is just over the horizon. If that is in fact the case, the latest delay in the LSM hinders the Marines’ ability to contribute to that fight in the not-so-distant future, given their plans for how their portion of that fight would play out. Above all else, it highlights a disconnect between urgent messaging on the threat and what’s needed to address it, and the actual procurement of those solutions.

Email the author: geoff@twz.com