The Pentagon is looking for help to turn a vision of future fleets of hundreds of low-cost highly autonomous drone boats able operate collaboratively to intercept “noncooperative” ships into a reality.

What is known as the Production-Ready, Inexpensive, Maritime Expeditionary (PRIME) Small Unmanned Surface Vehicle (sUSV) project might also a stepping stone to the acquisition of networked swarms of armed uncrewed watercraft or ones with electronic warfare suites. This might even include explosive-packed kamikaze types designed to ram into their targets and detonate. This is a capability pioneered by Iran, who subsequently transferred it to Houthi militants in Yemen, and that has now really come into its own in the course of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

The Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) recently put out a call for proposals for the PRIME project. First established on an experimental basis in 2015, DIU is charged with “accelerating the adoption of commercial and dual-use technology to solve operational challenges at speed and scale” from its headquarters in Silicon Valley in California and satellite offices in Austin, Texas; Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; and at Pentagon itself.

The video below shows a drone boat swarm the Navy conducted in 2014, as a very general example of relevant capabilities.

“The Department of the Navy has an operational need for small Unmanned Surface Vehicle (sUSV) interceptors, capable of autonomously transiting hundreds of miles through contested waterspace, loitering in an assigned operating area while monitoring for maritime surface threats, and then sprinting to interdict a noncooperative, maneuvering vessel,” DIU outlines as the core “problem” the PRIME project is looking to solve. “Interceptors will need to operate in cohesive groups and execute complex autonomous behaviors that adapt to the dynamic, evasive movements of the pursued vessel.”

DIU has deliberately left the requirements for the size and shape of the drones boats in question open ended.

“Linear dimensions are intentionally not specified in order to promote openness for innovative solutions,” a question and answer section for the PRIME project says. “Solutions should seek to satisfy the technical attributes and capabilities described in the Area of Interest.”

Offerers do need to submit drone boat designs capable of traveling between 500 and 1,000 nautical miles “in moderate sea states” with a total payload, including fuel, weighing 1,000 pounds. The sUSVs also need to have a sprint speed of at least 35 knots and sufficient fuel reserves to be able to loiter for “several days” in a designated area before returning to a recovery point. The requirements call specifically for a diesel-powered propulsion system, as well.

In terms of autonomy, the sUSVs have to be navigate on their own to a designated location via pre-planned waypoints and automatically sense and avoid other ships and maritime hazards along the way. Once there, it has to be able autonomously “follow or shadow” a maneuvering target and/or intercept it if instructed to do so, including “in crowded shipping lanes.” The onboard systems have to be able to perform these tasks even in GPS-denied environments and if the connection to its human overseers is disrupted or lost.

The Maritime Applied Physics Command and Control (MAPC2) system depicted in the video below is an example of an existing control architecture for drone boats that includes waypoint following and other semi-autonomous capabilities.

Any submitted designs “must be able to readily integrate third-party software and/or hardware for collaborative intercept capability, whether Government-furnished or commercial, by using open architectures, standardized or common interfaces, or other methods,” the PRIME notice adds, but more on this later.

DIU does not define just how cheap “inexpensive” might be when it comes to PRIME’s drone boats, whatever their performance and capabilities might be in the end. The project notice does say it is of “essential importance” for potential vendors to show that they can quickly ramp up production of their design to a rate of at least 10 per month/120 a year.

Furthermore, “compelling solutions will need to demonstrate a diversified and resilient manufacturing supply chain for key components such as hull, propulsion and steering, electric power, sensors, and compute, with the ability to justify production readiness and to elucidate supply chain risk areas,” according to DIU. “Submissions should include information on current production facilities and workforce, current production constraints, and any projected production expansion and/or investment.”

DIU also has a wishlist of secondary and tertiary “attributes” that would be desirable, but are not hard requirements.

The ability to “automatically adjust emissions control (EMCON) posture when in the vicinity of specific vessels and aircraft, or in specific geographic areas,” is one of the more interesting secondary attributes listed. This could help with missions to “successfully search for, localize, shadow, and intercept a noncooperative, maneuvering vessel of interest using techniques and sensor modalities that minimize probability of detection.”

Another secondary point of interest is for the sUSV to have a tethered aerial drone that can it can deploy to help find targets and to help with “other supporting missions.”

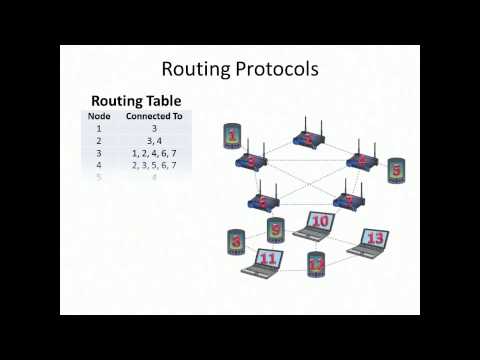

DIU also says “diversified, redundant, and adaptive communications,” which could include distributed “machine-to-machine data links and mesh networks” would be desirable. Mesh networking is already emerging a key component of future uncrewed concepts, whether it be for drones at sea or in another domain, particularly because of how difficult it is to jam them given their use of a large number of individual nodes. When it comes to PRIME, any such would not be limited to nodes within a swarm of drone boats. Tertiary nodes, including uncrewed aircraft, could be utilized, as well.

The video below provides a general overview of the concept of mesh networking.

“Automated contact recognition for classifying and identifying surface vessels of various types, to include recognition of hull shape, superstructure, masts, and hull markings such as letters and numbers,” is among the tertiary attributes. There is also interest in the “ability to accept a variety of modular payloads, sensors, and effectors.”

The MARTAC Devil Ray drone boat, a type the Navy has already acquired in small numbers, is an example of an existing uncrewed surface vessel with a modular design that can readily accept different mission packages, as is depicted in the video below.

Though the PRIME notice doesn’t elaborate, the U.S. military generally uses the term “effectors” to refer to various types of weaponry and electronic warfare systems.

“Flexibility with a variety of launch and recovery methods, such as amphibious ship well deck, deck crane/boat davit, or boat ramp, and the ability to be easily and safely transported by land, sea (including tow from a small craft), and/or air, without the need for considerable platform-specific handling or transport equipment,” is also a tertiary interest. So is “compatibility with long-term storage inside an intermodal shipping container, with the ability to quickly prepare and deploy the vehicle for high-tempo operations.”

Interestingly in terms of production, the list of tertiary attributes section above includes interest in designs that could be readily exportable to allies and partners. The question and answer section also says DIU will consider designs produced in full or in part outside of the United States. Expanding such a program beyond the U.S. military could create economies of scale and help lower the unit cost of each drone boat. This could also have operational and logistical benefits.

The full lists of secondary and tertiary attributes for PRIME are reproduced below:

Beyond the design of the drone boats themselves, DIU has a number of collaborative autonomy requirements regarding how it expects to the sUSVs to be able to work together.

Each one of the dorne boats has to have “the ability to execute adaptive, cooperative behaviors and deconfliction with proximate sUSVs, including in crowded shipping lanes or in a GNSS-denied [global navigation satellite system, such as GPS] environment, and especially as related to shadowing or intercepting a noncooperative, maneuvering vessel of interest,” DIU says. The “interceptors [also need to be able] to cooperatively and efficiently search for and localize a vessel of interest, especially using techniques and sensor modalities that minimize probability of detection.”

DIU wants the networked groups of uncrewed interceptor boats to be able to autonomously respond to the target dramatically changing its speed or course, or otherwise trying to throw them off, including by hiding among civilian vessels. The group needs to be able to adapt on its own to the loss of one or more individual drone boats.

There is also a requirement for “collaboration among homogenous sUSV interceptors, and furthermore enable teaming among heterogeneous sUSV interceptors with differing performance characteristics, sensors, and communications equipment.” This is a general benefit of networked drone swarms whatever domain they might be operating in. Since a swarm is the some of its parts, not ever drone in it needs to carry all of the systems required for a particular mission. This, in turn, opens the door to smaller and cheaper designs that can be tailored to perform a more limited number of tasks, or even just one, such as acting as a sensor node, weapons truck, electronic warfare plartform, or datalink relay.

Below is the full list of the required collaborative autonomy attributes:

The PRIME project details do not include any granular notional mission scenarios, but its not hard to see how these drone boats might be be employed operationally. Be able to sending out swarms of low-cost sUSVs to autonomously search for and shadow targets of interest would be a boon for finding threats sailing on the surface, and do so quickly. With maximum ranges of 500 to 1,000 nautical miles and the ability to loiter in a particular area for days on end, these uncrewed boat swarms would also just be able to dramatically increase general situational awareness across broad areas.

Recovery of the drone boats would not necessarily have to include traveling back to the original point of departure, either. Dedicated motherships and other recovery platforms could move to close the distance (or even just move into the loiter area directly for retrieval) depending on what threats are or are not found in the course of operations. This could functionally increase the overall range of the sUSVs, as well as allow them to be employed more flexibly.

As DIU’s secondary and tertiary requirements make clear, there is already interest in integrating additional capabilities, potentially including weapons and electronic warfare systems, into the PRIME swarms. This could allow the drone boats to launch swarming kinetic and non-kinetic attacks. This could also act as decoys to distract or confuse opponents, prompting them to waste time and resources (including valuable munitions) and helping to clear the way for other friendly forces.

It is worth noting that the Navy, as well as the U.S. Marine Corps, have been working to field or otherwise exploring various types of armed drone boats in recent years, and continue to do so. This includes types loaded with loitering munitions and ones that could be armed with Stinger short-range surface-to-air missiles to help protect friendly forces at sea.

The Navy has been experimenting with drone boat swarms for various applications for years now. The service also has a stated interest in being able to launch swarms of aerial drones – another capability the U.S. military as a whole has been actively pursuing – from uncrewed surface and undersea vehicles, as well as crewed vessels.

Then there is the matter of kamikaze drone boats with explosive warheads designed to blow up after strike a target ship or some other kind of littoral target, such as a bridge pylon. This is a concept that is not new, with the Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen being the first to really use it to effect starting back in 2017.

The Yemeni militants have continued to make use of this capability since then and are now employing kamikaze USVs as part of their current campaign against foreign warships and commercial vessels in and around the Red Sea. Just today, U.S. forces in the region destroyed one such Houthi drone boat, according to U.S. Central Command.

However, it has been the war in Ukraine that has really underscored the threat that kamikaze drone boats pose. Earlier today, Ukrainian authorities released a video showing a group uncrewed attackers sinking of the Russian Navy’s Project 12411 Tarantul III class missile corvette Ivanovets off the coast of the Crimean Peninsula. You can read more about that incident here.

Ukrainian forces have an increasingly diverse arsenal of kamikaze USVs, which they have been using in attacks against ships and coastal infrastructure for more than a year now. Some of these Ukrainian boats are said to have maximum ranges and top speeds roughly in line with what DIU is interested in for the PRIME program. The MAGURA V5, for example, can reportedly travel up to 450 miles and get up to 42 knots.

There are already signs that the U.S. military interested in fielding its own kamikaze drone boats. During an exercise focused on uncrewed capabilities in the Pacific last year, the Navy demonstrated the ability of a warhead-armed Ship Deployable Seaborne Target (SDST) to hit a moving towed target, according to Naval News. SDSTs are uncrewed Jet Ski-type watercraft that the Navy uses for various training and test and evaluation purposes.

“Loitering surface [emphasis in the original] munitions present a greater threat to ships because they can carry heavier payloads than similarly sized UAVs. Moreover, they are hard to detect in highly trafficked waterways and anchorages or during hours of darkness,” Marine Corps Maj. Michael McHugh, a member of the 2d Marine Expeditionary Brigade, wrote in a piece arguing for his service to acquire similar kamikaze drone boats in the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine last year. “Properly directed, they detonate at the waterline near propellers, magazines, or ballast-control systems, increasing the likelihood of shipboard flooding and catastrophic damage. … water-jet propulsion systems, satellite communications, optical infrared lenses, and other sensors combine to make them multifaceted weapons capable of attacking both maritime vessels and infrastructure.”

The ability to loiter, one of the key requirements DIU outlined for PRIME, would be a key attribute here. Swarms of highly autonomous kamikaze drone boats could be deployed into a particular area where they could lie in wait for potential targets. In addition to simply inflicting losses or otherwise harassing an opponents surface fleets, the sUSVs could help funnel them elsewhere in ways that are advantageous for friendly forces. This is a benefit that is also often cited in discussions about naval mining.

It is important to note that the collaborative swarming capabilities that DIU wants for PRIME are also represent a huge leap over the USVs that are being used currently in Ukraine and by the Houthis.

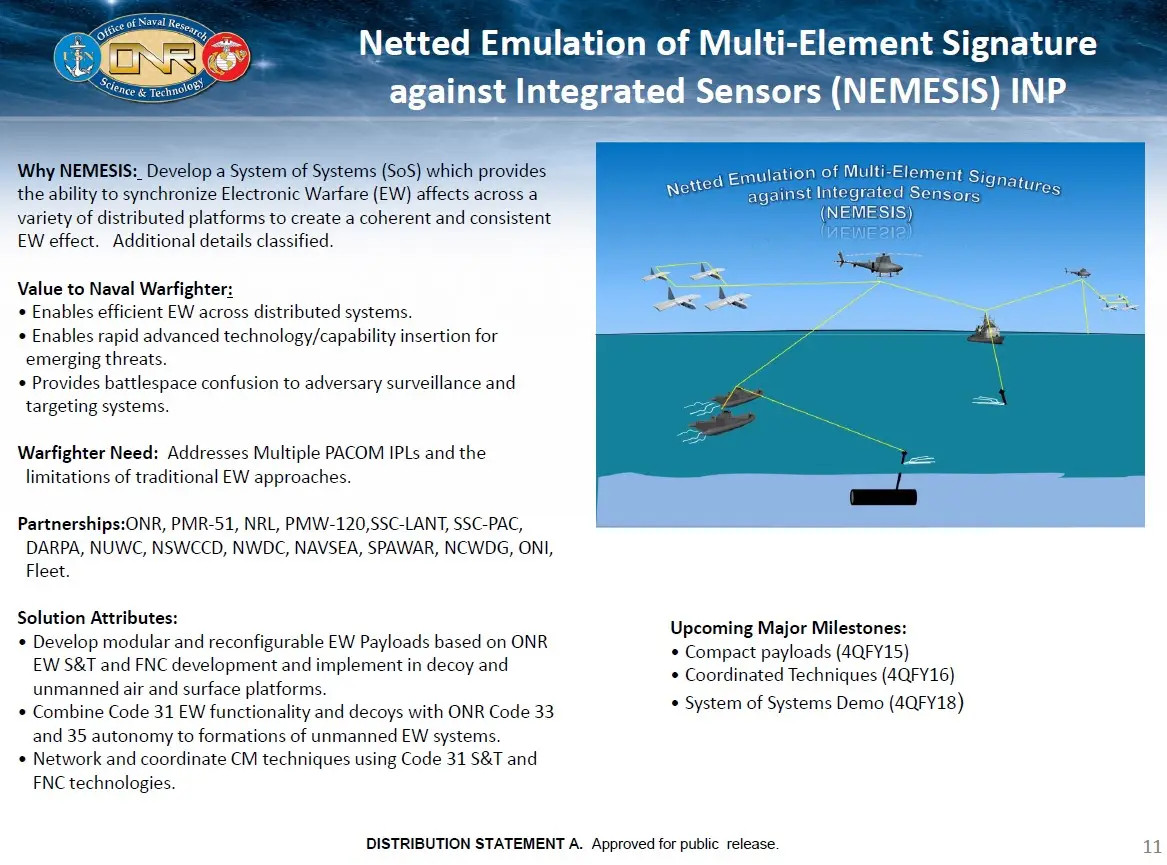

The possibility of PRIME drone boat swarms employing electronic warfare capabilities, including to act as decoys, is also fully in line with a broader, distributed, and secretive electronic warfare ecosystem the Navy has been working on a decade or more now. You can read more about what is known about the Netted Emulation of Multi-Element Signature against Integrated Sensors, or NEMSIS, in this past War Zone feature.

As already pointed out, swarms inherently allow for the mixing of capabilities into a unified whole. A group of PRIME sUSVs working together could include types armed with weapons, configured as kamikaze drones, set up to mimic larger surface ships, and more, to execute more complex missions.

PRIME drone boat swarms could be of interest to foreign allies and partners and DIU has already expressed its interest in baking exportability into the program. In particular, these uncrewed interceptor watercraft reflect the exact kinds of asymmetric capabilities that the U.S. government has been pushing the Taiwanese armed forces to acquire to help stave off any future intervention from the mainland. The narrow confines of the Taiwan Strait is the kind of littoral environment that ideally suited for the employment of swarming boats.

U.S. military wargames, and ones conducted on its behalf, have already consistently shown that aerial drone swarms could be a decisive factor in any future major conflict over Taiwan. China’s People’s Liberation Army, as well as Chinese state-run enterprises, have, unsurprisingly, been hard at work themselves developing swarming capabilities for various tiers of uncrewed aerial and maritime platforms.

With all this in mind, there is the potential that the Navy could use PRIME drone boat swarms to counter an opponents uncrewed surface vessels. The War Zone has highlighted in the past that when it comes to defending against swarms of aerial drones, one of the best options may well be swarms of friendly ones. The threat of incoming boat swarms, especially ones involving kamikaze types, present a similar need for large volumes of effectors of some kind to defeat them.

Low-cost swarming uncrewed interceptor boats could have value when supporting more mundane operations in low-threat environments, such as counter-narcotics, counter-smuggling, and counter-illegal fishing missions. In 2020, the Navy, together with the Marine Corps and the U.S. Coast Guard, released a tri-service naval strategy that focused heavily on pooling resources to challenge various kinds of malign activities short of war on a day-to-day basis.

“The ocean covers more than 70 percent of the world’s surface, and maritime transit is the backbone of international commerce. Waterways and shipping routes help provide for the freedom, prosperity, connectivity, and security of the billions of people who inhabit our planet,” DIU’s own description of the problem that PRIME is intended to help solve notes. “Fair and unimpeded access to the global maritime commons will remain vital throughout the 21st century, and fielding advanced ocean-going vehicles can help ensure freedom of navigation, not only for the United States, but also for our allies and partners across the globe.”

When the Navy might actually begin to field the kinds of drone boat swarms the PRIME program is envisioning remains to be seen. DIU’s work is centered heavily on smaller deals using novel contracting mechanisms to help get projects moving quickly, but often on a smaller scale than a traditional U.S. military procurement program. If PRIME initial stages show promise, the Navy, or another office with the Department of Defense, could certainly take over and significantly expand the project.

”You’ll see a lot of good concepts in the experimental phase, but then you present them to a larger force and some of these concepts end up dying because they don’t have the power of a legacy acquisition system,” Daniel Baltrusaitis, dean of the United Arab Emirates’ National Defense College, said in January during a panel discussion at the sixth annual Unmanned System Exhibition and Conference (UMEX) in Abu Dhabi, according to C4ISRNet.

This reality looks to be one of the main drivers behind the Pentagon’s new Replicator initiative. Replicator, which is notably not a program in of itself and has no direct funding attached to it, is geared toward helping find ways to accelerate the development and fielding of thousands of new uncrewed systems in the next two years or so.

Technical hurdles could impact PRIME, as well.

“You bring things out, they look good on a PowerPoint, they look good when they are tested back in the middle of America,” Navy Vice Adm. Brad Cooper, said at UMEX during the same panel where Mr. Baltrusaitis spoke, per C4ISRNet. “But when you bring them out in the Middle East and have them operate in the actual waters with the heat and the sand, some don’t work as well.”

Cooper is head of U.S. 5th Fleet and U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT), which collectively oversee the bulk of Navy operations in the Middle East. This includes the work of Task Force 59, which has been using the region is a real-world incubator to explore the integration of new uncrewed and artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities into day-to-day operations since its establishment in 2021.

At UMEX, Cooper specifically cited a previous DIU drone boat project that garnered more than 100 proposals, of which 15 were chosen for a demonstration in the Middle East. The admiral said that roughly half of those designs did not pass muster in the subsequent testing.

Altogether, especially based on Vice Adm. Cooper’s comments about the previous DIU effort, it very much remains to be seen how PRIME will progress. At the same time, the Navy clearly has an interest in acquiring swarms of drone boats with high degrees of autonomy that it could use to help find and intercept ships, and potentially attack them directly.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com