Joint land-sea operations were fairly uncommon in the Middle Ages. Rarer still was it for medieval generals to coordinate such actions across hundreds of miles and several months in advance. Almost unheard of was it to plan such complex offensives down to the week, in an attack that depended on speed, surprise, and timing. Yet this is exactly what Saladin did with his remarkable siege of Beirut in 1182.

Saladin is among the best-known generals of the Middle Ages, famous for his overwhelming victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187, in which he destroyed the Kingdom of Jerusalem’s entire army, and his showdown with Richard the Lionheart and the Third Crusade, which confined their territory to a sliver of coastline for the next hundred years.

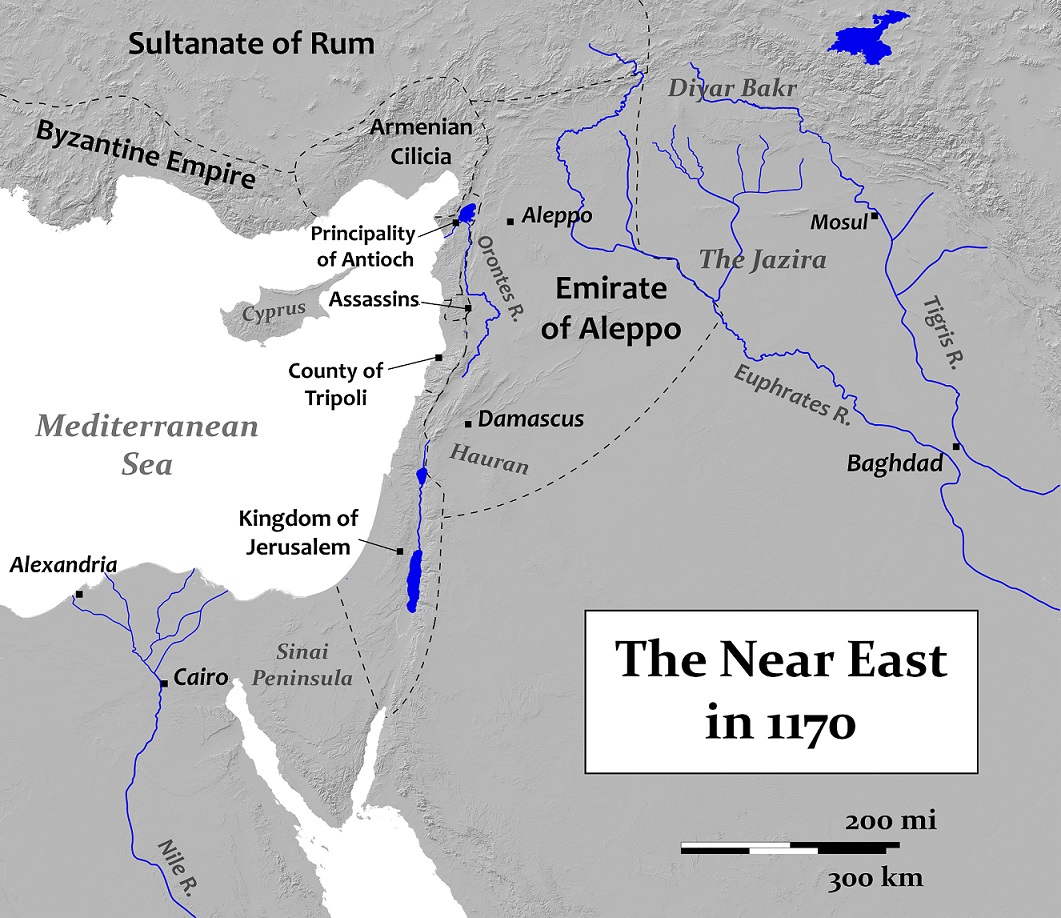

Less well-known are Saladin’s earlier exploits against these states. For nearly two decades before Hattin, he conducted a number of campaigns against the three Christian states which controlled the entire eastern shore of the Mediterranean – from north to south, these were the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Crusaders were tough and wily opponents. Although usually outnumbered, they played a superb defensive game, capitalizing on their strengths and refusing to leave an opening that their enemies could exploit. They also made the most of their geographic advantages: their frontiers were protected by imposing coastal mountain ranges, the river Jordan, and formidable deserts. This forced Saladin to experiment with a variety of approaches to land a decisive blow. It was during one such attempt that he launched his attack on Beirut.

Engaging the Crusader army

Saladin first rose to prominence in 1169, when he became governor of Egypt in the name of the emir of Syria. When his patron died in 1174, he embarked on an expansionary campaign against rival Muslim powers, and within two years he had carved out most of Syria. A general treaty secured recognition of these conquests and granted him the title of Sultan. He continued to campaign against the Crusaders for another four years until agreeing to a truce with them. But by 1182 war was rumbling on the horizon once more. A bitter succession dispute over the important city of Aleppo – the one part of inland Syria that he did not control – was drawing him into conflict with a large coalition of rival Muslim princes; meanwhile, the Crusaders had violated the truce that winter with a raid into Arabia and were engaged in piracy against Egyptian ships in the Mediterranean.

Saladin spent the winter of 1181-82 in Cairo, where he contemplated his actions for the coming year. His main effort was to be directed against Aleppo. This was the great metropolis of northern Syria, crucial for shoring up his control of the region. The high stakes meant that he would inevitably be drawn into conflict with other powers as far east as Mosul, and possibly even Persia. He, therefore, had to take action against the Crusaders before continuing north. It was important for reasons of prestige to retaliate for their incursions, but also for his standing in the Islamic world – he could not be seen to be prosecuting a war against his fellow Muslims while neglecting the holy war against the infidels.

In the spring of 1182, Saladin marched out from Egypt with a large body of troops. He reached Damascus towards the end of June, where he spent a few weeks gathering reinforcements and organizing his men before crossing the Jordan into the Kingdom of Jerusalem in mid-July. Detachments of marauders spread out ahead of the army to ravage the countryside, while the main body sacked towns along their route.

The army was shadowed by a substantial, but smaller, Crusader force, which on July 15 confronted them at the edge of an open plain. The Christian army arranged itself in a sturdy formation, with their archers and crossbowmen protected by a solid line of spearmen, behind which stood the knights. The Muslim cavalry, which mostly consisted of horse archers, swarmed around their ranks trying to put them in disorder, while the Christian knights occasionally charged out to beat them back.

The action incurred modest casualties on either side, both from the combat itself and the intense summer heat, but neither could break the other’s formation. Eventually, the Crusaders withdrew in good order to a nearby castle, where they encamped in an unassailable position. Even though Saladin had successfully forced them off the battlefield, they remained a live threat which limited his freedom of action. His army had consumed all the provisions in the neighborhood and he needed to disperse his men to forage and water their mounts; this was impossible without putting the scattered elements in jeopardy, leaving him no choice but to withdraw the army over the Jordan.

The Crusaders had shown just how difficult they were as adversaries, able to flummox a stronger force through the combined use of maneuver and the protection of fortifications. But as much as Saladin might have hoped to destroy the Christian army then and there, he had a more pressing matter to attend to: a rendezvous with his fleet.

The expedition against Beirut

Since coming to power in Egypt, Saladin had focused much of his attention on rebuilding the country’s navy. It had fallen into disrepair over the past several decades, allowing the Italian maritime powers such as Venice and Genoa to dominate the sea lanes. His efforts quickly paid off: although he could not go toe-to-toe with the Christian sea powers, he soon had a fleet that could undertake limited actions at sea. Before setting off for Syria in the spring of 1182, Saladin had ordered his ships to sail up the coast to Beirut, where they were to meet him in the middle of the summer. After recrossing the Jordan on July 18, the sultan marched north to the Beqaa Valley, in the east of modern Lebanon, where his men found forage and water in abundance. Lookouts were posted on the peaks of the nearby coastal mountains, and after a few days, they spotted sails on the horizon. Saladin immediately crossed the mountains with his army, leaving his siege equipment behind to move faster and arrived at Beirut on the first day of August.

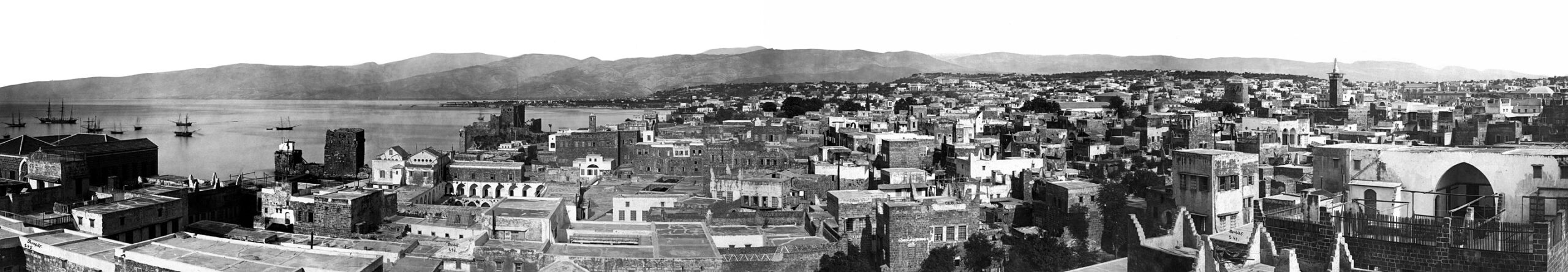

Beirut sits on a triangular promontory, about five miles wide at its base, which juts out into the Mediterranean Sea. The medieval city occupied just the northwestern tip, and the rest of the plain was covered in rich fields and orchards. This area was accessible from the north and south only by a very narrow road that ran down the coast, hemmed in between sea and mountains. From a military perspective, it was a virtual island, easily defended against any land forces. Saladin’s rapid march took the city entirely by surprise, however, and he traversed the mountain passes unopposed. Beirut itself had been left with a small garrison, and he now held the advantage of its defensible position: he could block the coastal route against any relief force from the south, while his surprise move bought him several days before the enemy could even mount a response. He immediately got to work, setting up his men around the city and subjecting it to a near-continuous rain of arrow fire.

Rumors of this soon reached the Crusader army, which was still encamped near the Jordan frontier. But there was hesitation at first: some believed that Saladin had continued north to deal with Aleppo, while others were nervous that he would reappear on the Golan Heights. Reports of raids in the south added to the confusion – Saladin had pulled off another difficult feat of coordination by instructing his forces remaining in Egypt to time a raid against the frontier with the fleet’s arrival at Beirut. As more reports trickled in, however, the Crusaders were able to distill a signal from the noise: there was no doubt that Saladin had moved in strength against Beirut. The Christian army set off for the coast at once, sending word ahead to the port cities to make ready whatever ships lay in harbor.

Meanwhile, the siege was not going well for Saladin. His lack of siege equipment left him only two options for taking the city: tunneling under the walls or scaling over them. The first option was safer, so his engineers prepared tunnels to undermine the fortifications. The defending troops, though few in number, organized the townspeople into working parties and dug mines of their own to counterattack, leaving the Muslim army no choice but to attempt a frontal assault with scaling ladders.

It was at this point that Saladin began to feel the absence of his siege engines. His large counterweight trebuchets could bring down walls and towers, but it was his smaller man-powered trebuchets, also called mangonels, which really made the difference. These could fire up to four times a minute, showering the battlements with stones which made it dangerous for defenders to remain on the walls. They functioned much like modern artillery in an assault, suppressing the enemy long enough for the attacking infantry to rush forward with their ladders. Although Saladin’s vast array of archers put up sheets of arrows to force the defenders’ heads down, the townspeople met the assault with a hail of stones, arrows, and other missiles of their own which drove his men back.

It is not entirely clear what role the fleet played in all this. It might have attacked the sea walls or tried to penetrate the harbor, distracting the defenders’ attention from the main assault; it also likely carried provisions for the lightly-equipped land forces, and at the very least kept reinforcements from getting in and messengers from getting out. But after three days of fruitless efforts, Saladin allowed his fleet to return home and pulled his army back a short distance to reconsider his options.

The sultan decided upon a more deliberate approach. He sent his cavalry across the plain to cut down the surrounding orchards, probably to provide wood for siege equipment, and sent some of his infantry to construct a stone rampart across the narrow road from the south. But after a few days, his men intercepted a Christian messenger who revealed that enemy ships would be ready to sail up the coast with their army in just three days. Saladin was prepared for an attack by land, but he was astonished that the Crusader navy was able to get underway so fast. His own fleet had already departed, leaving him no means to protect his blocking force from being outflanked. Choosing the path of discretion, he gathered his army together and withdrew over the mountains.

Saladin’s siege of Beirut was a failure, but it was not a costly one. It was a gamble with very little downside, which, if it had succeeded, would have paid off immensely. Such a defensible enclave would have cut the Crusader states in two, preventing the two halves from sending troops to the other’s aid, and it would have given his fleet a safe harbor on the Syrian coast. Failure did not discourage him, however, and he spent the next year campaigning against other Muslim powers in Syria and Mesopotamia. This was an enormous success, which resulted in the surrender of Aleppo in June 1183.

There was no surefire formula for success against disciplined adversaries such as the Crusaders. Winning required experimenting with a multitude of approaches in order to see what worked and discard what didn’t. The siege of Beirut should be seen as one iteration in a long series of these experiments. From the perspective of planning and execution alone, it was an impressive feat: it required timing the fleet’s voyage up the coast, his army’s march up from Egypt (during which he launched an incursion across the Jordan to keep the Crusader army fixed there), and diversionary raids from Egypt. More amazing still is that it nearly worked. It is easy to imagine how things could have gone another way – if he had his siege equipment delivered by sea, for instance, or if he kept the fleet around long enough to protect the shore.

Ultimately, Saladin found a much more workable solution to overcome the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Rather than try to distract the enemy army in advance of an important siege, he used another siege to bait them into battle on very disadvantageous ground – this was the famous Battle of Hattin in 1187. His plan worked better than he could have imagined and the Crusader enemy army was crushed – only a few hundred out of over 20,000 soldiers escaped. This victory was not a one-off fluke, but the product of the lessons he had learned from several previous campaigns, including the siege of Beirut.

It was Saladin’s willingness to undertake such complex and daring ventures that marks him as a visionary general, unique for his time.

Benjamin Duval is a historian specializing in the life and military career of Saladin. For more on Saladin’s career as a general and how he developed his method of warfare, check out Saladin the Strategist by the same author.

Contact the editor: oliver@thewarzone.com