The war in Ukraine has so far seen a very wide variety of Russian military aircraft employed in combat, with rumors of others being involved, and certain more unusual types deployed to bases close to Ukraine. Perhaps the most curious Russian military aircraft type to have been noted operating so far, albeit on the periphery of the conflict, is an extremely scarce amphibian — the Beriev Be-12 ‘Mail’ that was first flown in 1960 and which then served throughout the rest of the Cold War.

In recent days, different videos and photos have emerged that appear to show Russian Navy Be-12s operating over the coast of Russian-occupied Crimea. It’s not possible to verify the dates of all of these, but at least one video was purportedly taken on August 16 and shows one of the twin-turboprop amphibians — nicknamed Tchaika, or seagull —flying low over holidaymakers on a Crimean beach.

Another image, which looks to be a screen capture from a separate video, presents a very similar scene. It’s described as having been taken on the northwest coast of Crimea, specifically, on Lake Donuzlav (45.337446,32.967088). A date is not provided but it’s been suggested it was “possibly recent.”

Another apparently recent video shows a Be-12 flying along the Crimean coastline, this time at a higher altitude.

Another was sent to us by a source that says it was taken in July of this year.

That the Russian Navy still has Be-12s in Crimea is hardly a secret. Indeed, satellite imagery showing the aftermath of the apparent Ukrainian attack on the naval airbase at Saki revealed at least two Be-12s parked there. These avoided the fate of at least 10 Su-30SM Flanker and Su-24M/MR Fencer combat jets that were seriously damaged or destroyed in what remains a highly mysterious incident.

However, the two Be-12s at Saki are almost certainly no longer operational, with no recent reports of activity there by this type. Most likely, they are some of the former Ukrainian aircraft left here when Russia took control of the base, and which were unable to be evacuated to elsewhere in Ukraine.

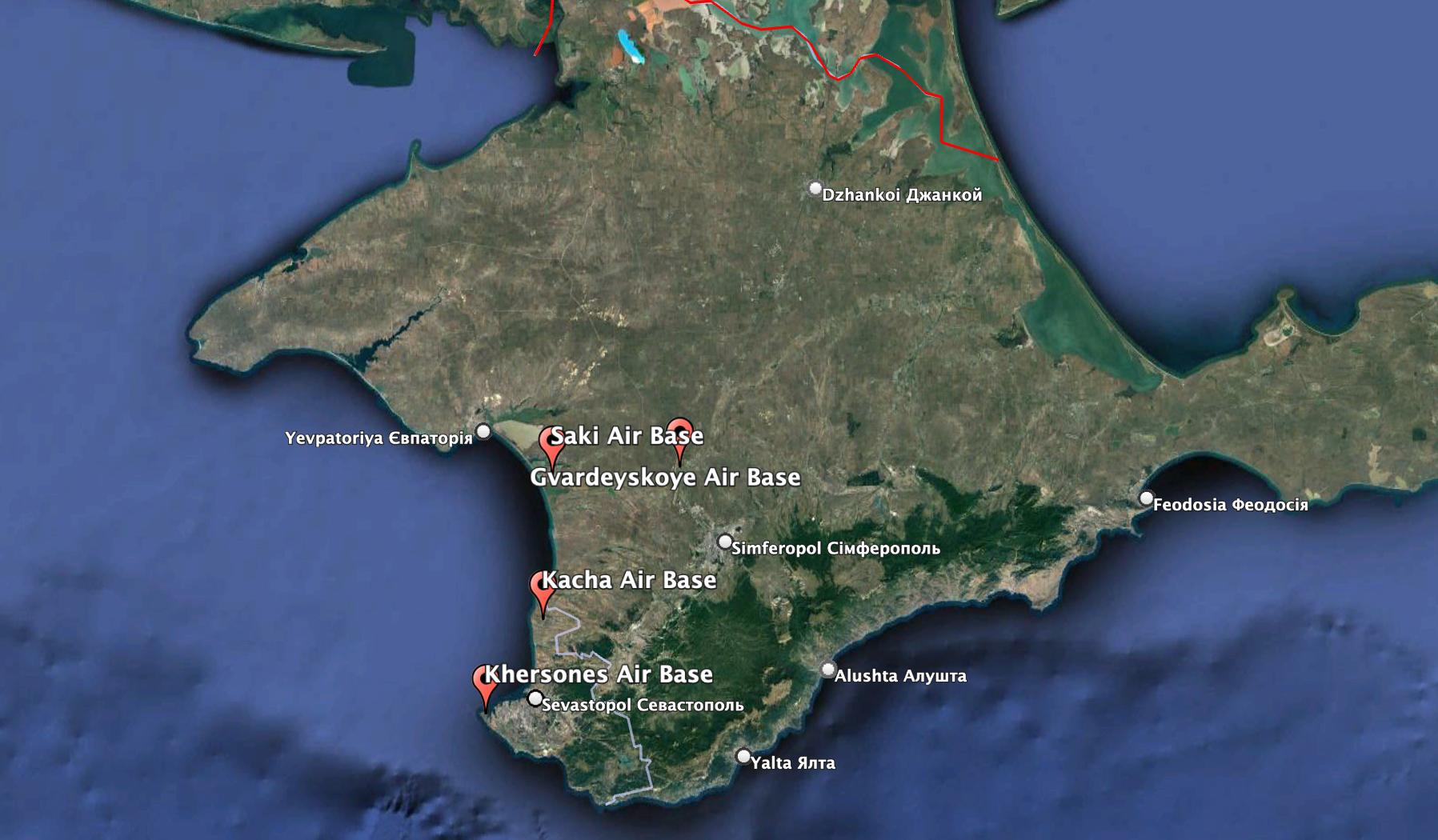

Otherwise, the regular operating location for Russian Navy Be-12s is Kacha Air Base, also in Crimea, near the Black Sea Fleet’s major naval base at Sevastopol.

Kacha is home to the Russian Navy’s 318th Independent Composite Aviation Regiment, or 318 OSAP, part of the Black Sea Fleet. As well as a tiny number of Be-12s, the unit flies Ka-27/29 Helix helicopters that are used for a variety of tasks, including anti-submarine warfare, search and rescue (SAR), and amphibious assault. There is also a resident transport and rescue squadron with twin-turboprop An-26 Curl transport aircraft, plus its own Ka-27 and Mi-8 Hip helicopters.

The 318th OSAP is also responsible for an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) squadron (possibly since expanded to a regiment), flying the Forpost drone from the nearby Khersones airfield.

The number of Russian Navy Be-12s that are still operational at Kacha is unconfirmed, but most authoritative sources suggest that it’s between four and five.

These aircraft have long resided in Crimea, including through the turbulent recent history of the peninsula.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Black Sea Fleet was divided between Russia and Ukraine, with Be-12s going to both countries. With Ukraine agreeing that Russia could continue to make use of naval facilities in Crimea, under a leasing arrangement, the Russian Be-12s remained at Kacha. Prior to 2014, this was one of two Russian naval airbases on the peninsula, the other being at Gvardeyskoye.

Things changed drastically when Russian forces seized Crimea in 2014, with Moscow establishing new military units there and relocating the combat aircraft fleet from Gvardeyskoye to Saki. Gvardeyskoye is another base that’s been reported to have come under recent attack, although satellite imagery does not appear to show any apparent damage there.

However, while the Russian combat jets based in Crimea have been used to fly offensive missions over Ukraine, the military value of the Be-12s in this conflict would, at first glance, appear to be almost non-existent.

Developed as a short-range anti-submarine warfare (ASW) amphibian, the Be-12 has a normal crew of four, comprising two pilots in the upper cockpit, a navigator in the glazed nose station, and a radio officer in the cabin.

First flown in October 1960, the Be-12 began to be delivered to Soviet Navy units in 1964 and the amphibian was officially commissioned into service in November 1968. A total of 140 production aircraft were built and issued to the Baltic, Black Sea, Northern, and Pacific Fleets.

The aircraft’s high-mounted tapered wing, wingtip floats, and boat-like hull were tailored for amphibious operations, allowing the Be-12 to fly from land bases as well as from the water. Beginning in 2006, however, the aircraft were prohibited from operating from water, reflecting the overall age of the airframes and their dubious seakeeping qualities. This later restriction reportedly changed years later, at least for a small handful of them.

Of the 140 production aircraft, 130 were completed in anti-submarine warfare (ASW) configuration, with a submarine-detection system including a search/attack radar in the nose, a magnetic anomaly detector in the tail ‘sting,’ radio sonobuoys, signal-processing equipment, plus navigation and computing gear.

A weapons bay in the bottom of the fuselage and four underwing pylons can carry over 3,300 pounds of stores including depth charges, torpedoes, mines, and marker bombs.

But with the Ukrainian Navy having no submarines in service, the value of an ASW amphibian, especially one that is now extremely dated, is hugely questionable. Moreover, as submarines have become increasingly difficult to detect, it’s hard to imagine that the aircraft’s vacuum-tube electronics, last upgraded in the mid-1970s, would have much utility in finding and prosecuting modern diesel-electric boats, which are notably quiet.

On the other hand, in an uncontested environment, the Be-12’s reconnaissance capabilities could be useful, with the radar still able to provide a basic situational awareness picture of the coastline, as well as detect ships and submarines’ periscopes. Previous training has included searching for combat divers along the coast and the Be-12 could be useful for detecting any Ukrainian special forces that might be covertly inserted along the Crimean coastline. Teams like these, after all, may have been responsible for at least some of the recent incidents directed against Russian military infrastructure in Crimea.

Further to this, the Be-12 could lend itself to basic sea control duties. In the current context of the Ukrainian war, this could involve Identifying ships and monitoring sea traffic in support of the blockade around Ukrainian ports.

Perhaps more useful would be the SAR version, the Be-12PS, which has the ASW gear and weapons deleted, with the addition of medical and rescue equipment, including an air-droppable motor dinghy. The Be-12PS can also carry 13 survivors, although that really isn’t too relevant if it can no longer land on water.

Incidents such as the sinking of the Black Sea Fleet cruiser Moskva show that the need for SAR aircraft in the Black Sea is very real.

A 2018 report in AirForcesMonthly confirmed that, of the last seven Be-12s active in the Russian Navy, four were indeed of the SAR version, with one more in a dual-role ASW/rescue configuration. The current fleet composition is unclear, but it seems likely at least some are SAR variants.

Regardless, any Be-12 variant would be strictly limited in terms of where it can operate, with a never-exceed speed of only 360 miles per hour, minimal agility, and no self-protection equipment. With Russia having so far failed to establish air superiority over much of the conflict zone, it’s likely that these very vulnerable aircraft don’t venture that far from their home base and the greater Black Sea area away from Ukrainian controlled coastline.

Meanwhile, recent developments suggest that the Be-12s (not to mention other Russian Navy aircraft) are now also at risk on the ground. Indeed, yesterday the Defense Intelligence of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine claimed that at least 24 fixed-wing and 14 rotary-wing Russian military aircraft had recently been evacuated from Crimean bases, following a “series of explosions at military infrastructure facilities” there, although there was no mention of Be-12s being moved.

It could also be envisaged that the Be-12 might be used for light transport and liaison duties between different airfields in Crimea, although several An-26s are also on hand for these kinds of missions and would be much more suitable. Potentially, the Be-12 could play a role in transporting small raiding parties to the Ukrainian coast.

One remarkable niche role that the Be-12 has practiced in the past is the bombing of coastal targets. However, this would only be practical against an entirely undefended target, with this kind of mission requiring a straight and level approach to be flown in the daytime, with the delivery of unguided bombs.

Most likely, perhaps, the few Russian Be-12s still flying are conducting routine training sorties in the local area, to keep their crews current for a range of different mission profiles. Other training-related support activities for the type include dropping targets for live-fire training by air defense units, both land-based and ship-based.

Despite its limitations, Russia has stuck with its Be-12.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, 55 were left in Russian service and the aircraft was actually officially decommissioned in 1992. In fact, an oddity of the Russian (and previously) Soviet commissioning/decommissioning processes is that they don’t necessarily reflect actual operational activity. Remarkably, however, the Be-12 has remained in service ever since. Today, the only active examples are home-based at Kacha.

It’s also worth noting that, at least until relatively recently, the Ukrainian Navy also operated the Be-12, with two examples latterly active at Kul’bakino Air Base near Mykolayiv in the south of the country. Reportedly, they last flew in 2014 and, as of late 2019, they were both undergoing repair. It’s unclear if they ever returned to the air.

Four (some reports state five) Russian Be-12s underwent major overhauls at Taganrog between 2012 and 2013, adding reworked engines and propellers, and reinforcing the continued importance of the type. After this work, the Be-12s were able to operate from the water again, although it’s unclear how often this is actually practiced, especially as it imposes far greater stresses on the airframe.

The annexation of Crimea provided additional facilities to maintain the Be-12, with Russia taking over the plant at Yevpatoria, which had overhauled these aircraft in the Soviet era. Reportedly, at least two examples have gone through overhaul here since the annexation. Around the same time as Russia took Crimea, there were also the first reports of plans for an upgrade of the Be-12’s ASW systems, although there is no evidence that this was ever carried out.

However, with around a dozen aircraft at different locations judged suitable for reactivation, limited flying hours on each airframe, and no apparent shortage of spares, Russia might be able to operate its token fleet of amphibians for some time to come.

In the meantime, as long as Russia holds Crimea, it looks like these venerable amphibians will continue to appear periodically over its coastline, seemingly very much on the margins of Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com