More and more evidence is emerging of Russia’s latest Mi-28NM combat helicopters being used in the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine. These helicopters also appear to be increasingly employing the new-generation LMUR, or izdeliye 305 missile, in combat. While The War Zone previously looked at the use of LMUR in Ukraine, we had not definitively seen the missile in action until now.

Before we get to the first iron-clad visual documentation of the LMUR’s employment in the conflict, here is some key background on its launch platform.

Havoc’s genesis

The history of the Mi-28 stretches all the way back to December 16, 1976, when what was then the Soviet government ordered a new-generation combat helicopter to replace the classic Mi-24 Hind. Two helicopters were developed to meet this requirement, the Mi-28 from Mil, and Kamov’s Ka-50 (then a single-seater). Over many years, these two attack helicopters competed for Soviet and then Russian Ministry of Defense orders, with changing fortunes.

Finally, in the late 2000s, both types entered production and are today in service in their improved night-capable versions: the Mi-28N and Ka-52 (now a two-seater). The Mi-28N, which has the Western reporting name Havoc-B, is manufactured by Rostvertol at Rostov-on-Don; the same factory also makes Mi-35M Hind combat transport and Mi-26 Halo heavy-lift helicopters.

The first Mi-28N helicopters were accepted by what was then the Russian Air Force on January 22, 2008, when they were delivered to the 344th State Combat Training and Flight Crew Conversion Center in Torzhok. Subsequent deliveries were made to operational units at Budyonnovsk (starting in March 2009), Korenovsk (2010), Zernograd (2012), Ostrov (2013), Vyazma (2014), Dzhankoy (2014), and Pushkin (2016).

As of early 2023, Russian Army Aviation (a branch of what is now the Russian Aerospace Forces, or VKS) has about 110 Mi-28s, considering the loss of a dozen of these helicopters in the war with Ukraine starting in 2022. The basic version is the Mi-28N. Less common is the Mi-28UB (only 24 of which were produced), which received a mast-mounted N025 radar, lacking on the Mi-28N, and dual controls. Even rarer at this point is the latest Mi-28NM version — it’s doubtful that more than 10 are in service.

Video of the radar-equipped Mi-28UB during a live-fire exercise in the Krasnodar region, March 2020:

Avangard-3: Havoc modernization

With the development of the night-capable Mi-28N completed, on December 24, 2009, Mil received a contract under the Avangard-3 (vanguard) research-and-development program. This was a thorough modernization of the basic helicopter that resulted in the Mi-28NM version. The prototype, number ‘701,’ performed a first hover at the Mil company’s site in Tomilino on July 29, 2016; a first full-profile flight followed on October 13. In March 2019 it was briefly deployed to Syria for an apparent combat evaluation. On October 31, 2017, Rostvertol received an order for two Mi-28NM helicopters as part of an initial production series. They were completed in April 2019, as numbers ‘70’ and ‘71,’ and were used for further tests.

On June 27, 2019, with President Vladimir Putin in attendance at the ARMY defense exhibition at Kubinka near Moscow, the defense ministry signed an order for 98 Mi-28NM helicopters to be delivered between 2020 and 2027. The first two helicopters from this order, numbers ‘721’ and ‘731,’ were shown at Russia’s International Aviation and Space Salon (MAKS) in 2021. Andrey Boginsky, the CEO of Russian Helicopters, of which Mil is a subsidiary, specified later that the defense ministry would receive six helicopters per year between 2020 and 2022, and then 16 per year between 2023 and 2027. That indicates a plan to have 18 helicopters ready by the end of 2022. There is no detailed information about the execution of this order; only a few Mi-28NM are actually known from the available photos. In particular, there is no information about deliveries in 2020 (and in those days such news was hardly concealed); in 2021, the delivery of a small batch of two or three helicopters was reported.

At the ARMY exhibition on August 16, 2022, the defense ministry placed an order for another batch of Mi-28NMs, of unknown size. This is strange, considering the large contract for 98 helicopters placed just three years earlier. Perhaps plans have been revised as a result of the war against Ukraine.

The Mi-28NM differs from the N-version mainly in having upgraded mission systems and weapons. It introduces the BRLK-28 radar system that includes an N025M radar mounted atop the rotor mast, an OPS-28M Tor-M electro-optical turret carried in a much bulkier cylindrical housing under the nose and a new SMS-550 turret for the pilot (seated at the front). Both crew members are provided with an NSTsI-V helmet-mounted sight and display.

Developed by GRPZ at Ryazan, the N025M radar operates in the Ka- and X-bands (the N025 on the Mi-28UB works in the Ka-band only) for surface mapping, detecting surface targets, and indicating targets for the electro-optical sight, as well as weather and air-to-air functions; a third channel is the L-band used for identification friend or foe (IFF). The N025M radar, like the basic N025, cannot assign targets directly to the weapon and instead only indicates their initial coordinates to the OPS-28M electro-optical turret.

The Mi-28NM’s L370V28 Vitebsk self-defense suite combines L150-28M radar, L-140M laser, and L370-2 ultra-violet warning receivers, a countermeasures-launching system, and an L370V28-5L laser-based directional infrared countermeasures (DIRCM) system. A new KSS-28NM (S-406-2NM) communication suite enables the helicopter to operate within the army’s aviation command system.

Havoc at war

Standard Mi-28Ns first took part in combat operations in Syria in March 2016. Russian forces lost at least two Mi-28Ns in Syria. A helicopter from the Budyonnovsk regiment crashed near Homs on April 12, 2016, reportedly due to pilot error while flying at night; the crew was killed. Another helicopter crashed on October 6, 2017.

The Mi-28N and Mi-28UB have been operating over Ukraine since the beginning of the full-scale invasion last February, although they are less often seen than Ka-52s, suggesting they may be used less frequently, although this is hard to determine with accuracy. Either way, Ka-52 losses are three times higher than those of the Mi-28s and have already exceeded 30 helicopters. This compares to around a dozen Mi-28s. (The total number of helicopters of each type in Russian service prior to the invasion was similar, at around 110 of each). Typically, the Mi-28 helicopters in Ukraine are armed with 80mm and 122mm unguided rockets, and sometimes also four 9M120 Ataka (AT-9 Spiral-2) anti-tank missiles.

With man-portable air defense systems, or MANPADS, increasingly ubiquitous in the conflict, after a few weeks of fighting, Russian (and Ukrainian) helicopters began firing at ground targets by launching their unguided rockets in a climb. The helicopter approaches at a very low altitude, then pops up, fires a salvo of rockets, and quickly turns again at low altitude. As the rockets launch, the helicopter typically launches decoys in bursts. As The War Zone has discussed in the past, the accuracy of such fire is lower, but the safety of the helicopter is much improved. Virtually all attack helicopter operations in the war are conducted like this and Su-25 Frogfoot attack aircraft also operate in a similar way.

The latest Mi-28NM version of the Havoc was seen in the Ukraine war for the first time on October 15, 2022. A photo published by the Fighterbomber Telegram channel showed a helicopter, probably number ‘41,’ although this had been crudely painted over. The helicopter carried a B13L1 launcher under the wing, containing five 122mm unguided rockets.

A large letter ‘Z’ was painted on the heat suppressor covering the engine nozzle, indicating that the helicopter belonged to the Western Military District (MD). Nothing is known about any operational unit that has already received Mi-28NM helicopters. Most likely, the Mi-28NMs operating in Ukraine are piloted by crews from the 344th State Combat Training and Flight Crew Conversion Center in Torzhok; this is also in the Western MD area. Later, several more photos and videos have shown Mi-28NMs in Ukraine.

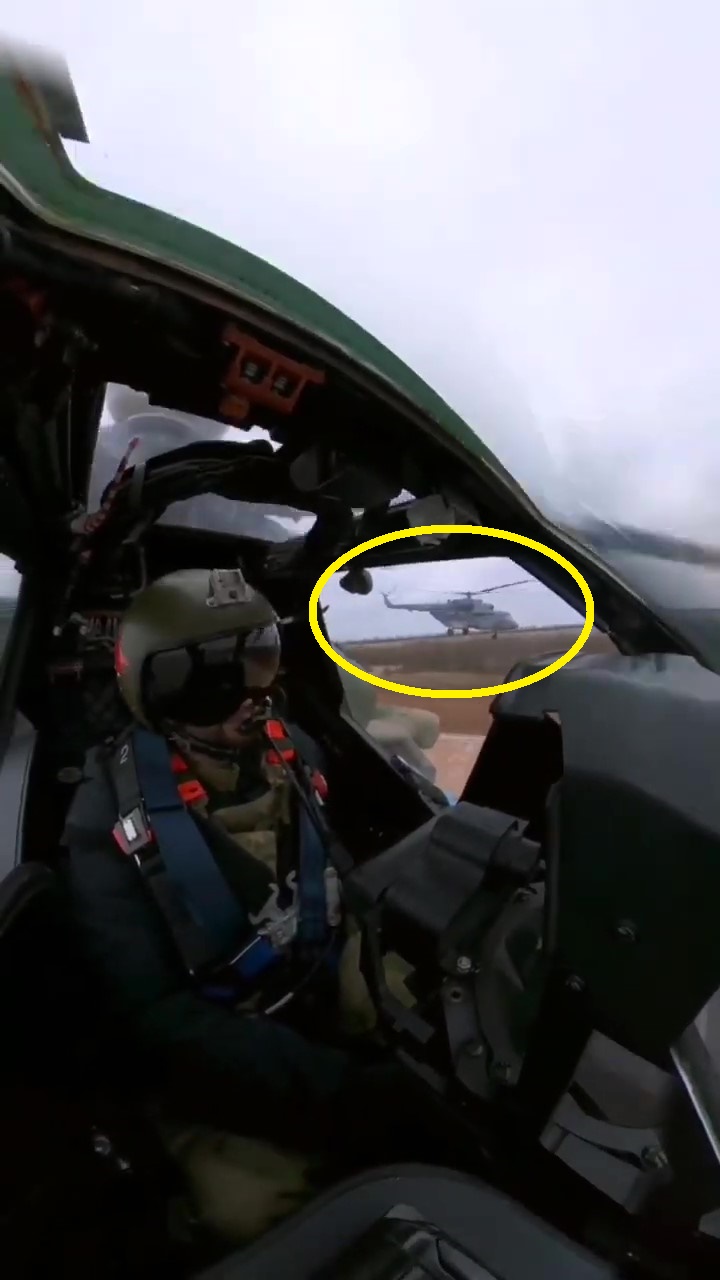

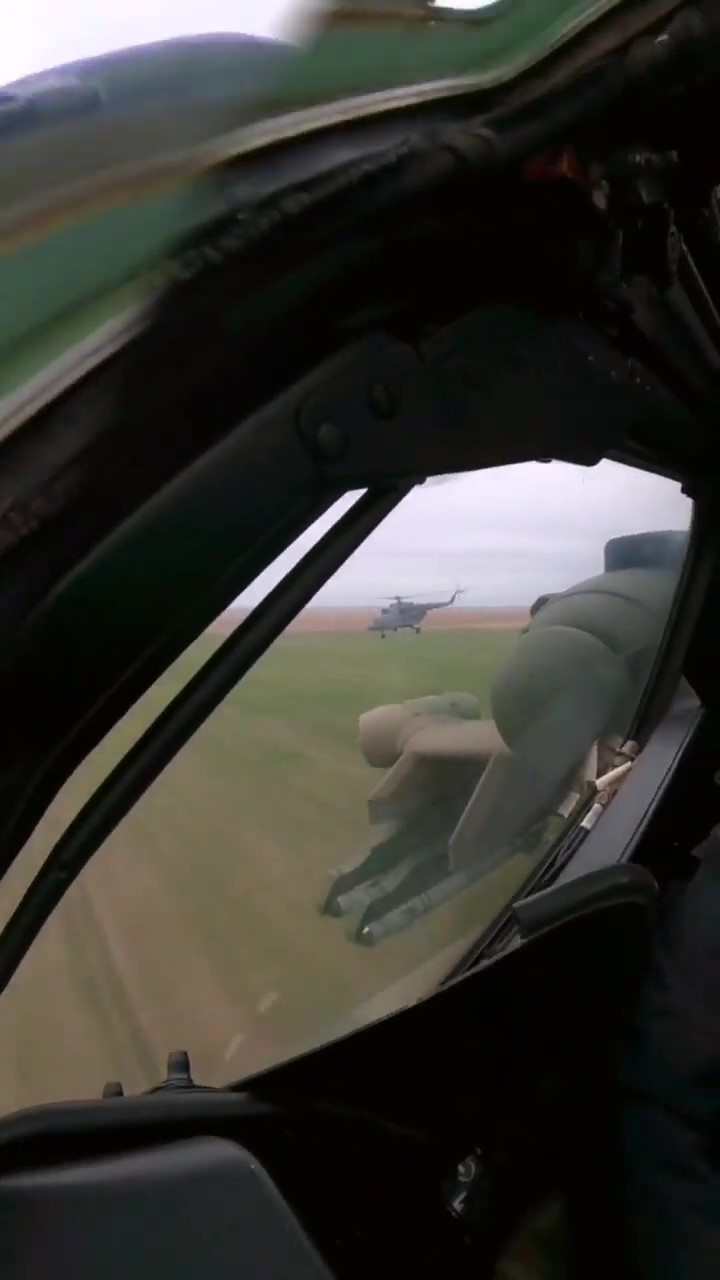

Finally, on January 14, 2023, the Fighterbomber channel published a video taken from the pilot’s cockpit of a Mi-28NM during a mission using the LMUR missile. The film has been heavily edited and includes day and night activities.

In the video, a pair of Mi-28NM helicopters depart for a mission, accompanied by a Mi-8 Hip combat transport helicopter; its task is to evacuate the crew in case one of the helicopters is shot down.

The video shows the interior of the Mi-28NM pilot’s cockpit (but not the front operator’s position). This looks similar to the standard Mi-28N cockpit, with two multifunction displays arranged side-by-side and a set of basic analog instruments. A new addition is the ILS-28NM head-up display, which has a less substantial framework than the previous ILS-28M.

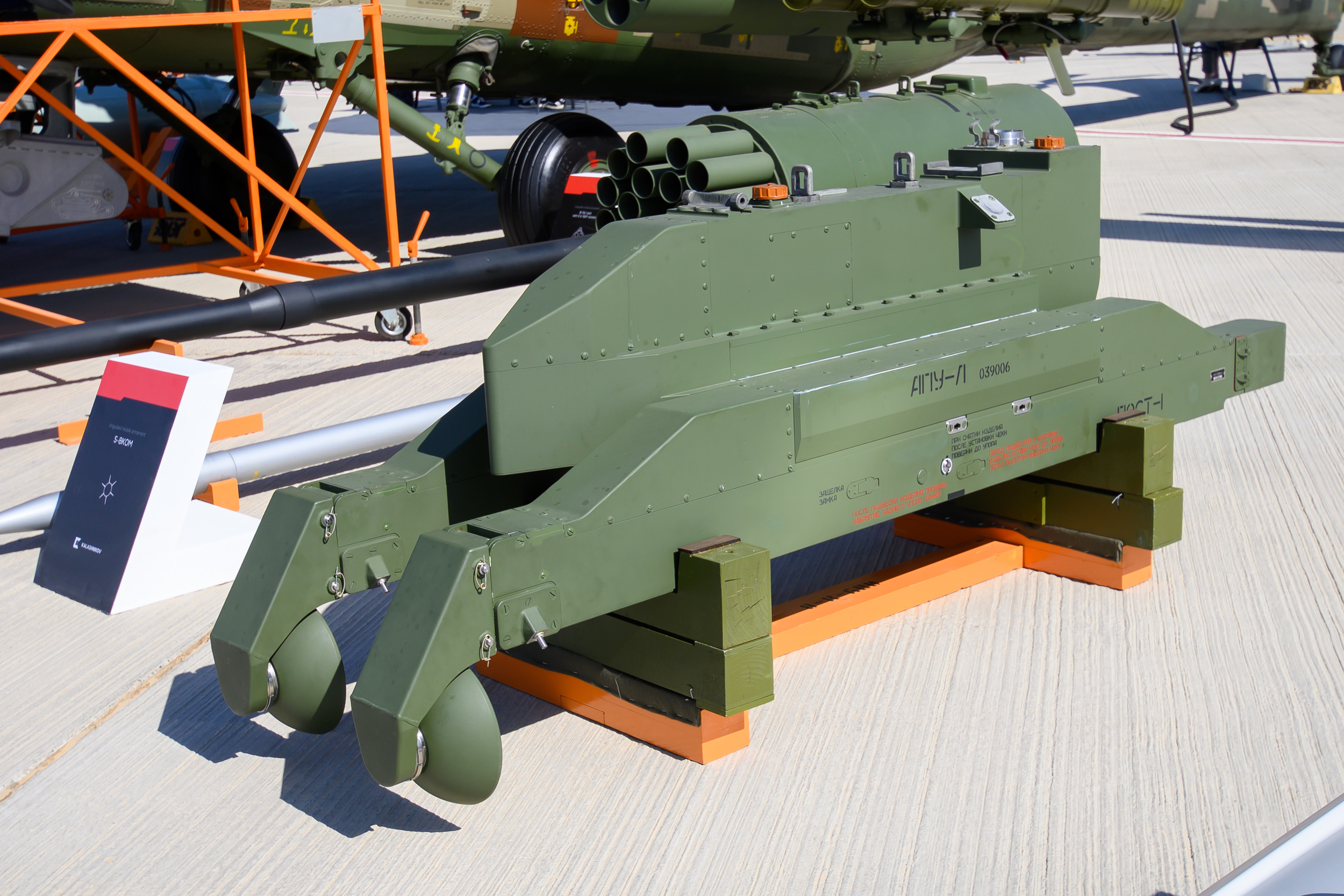

The helicopter carries two LMUR missiles on a twin APU-L rail on the outer pylon under the right wing; the other pylon is empty. It’s not possible to see exactly what’s hanging under the left wing, except for an extra fuel tank. In another video, published a few days earlier by the Ugolok_Sitha channel, a Mi-28NM is seen carrying one LMUR missile under its right wing (on an APU-L twin rail), with a B8V-20 rocket launcher and an additional fuel tank under the left wing.

LMUR missile launch

The most interesting aspect of the first video is the LMUR missile launch sequence. When suspended on a rail launcher, the missile seeker is covered with a cap that protects it from dirt during low-level flight. The cover is raised directly before the launch. The missile in the video hits a building, which of course doesn’t mean anything — the footage could easily have come from a completely different occasion.

After launching the missile, the Mi-28NM does not rapidly fly in the other direction at low altitude, nor does it deploy flares, which is what other helicopters are usually seen doing in this conflict. This suggests that it was launched from a long distance, outside the range of Ukrainian anti-aircraft defenses. After all, the maximum range of the LMUR missile is over nine miles. The shape of the antenna of the AS-BPLA missile-guidance datalink installed on the Mi-28NM indicates that it has viewing angles of +/-90 degrees from the helicopter axis, meaning the helicopter is able to maneuver within these limits after the missile launch.

The LMUR, which stands for Lyogkaya Mnogotselevaya Upravlayemaya Raketa, or light multipurpose guided missile, is also known as the izdeliye 305. It’s a new weapon that started tests on the Mi-28NM in 2019. The War Zone has already written in detail about the missile and its protracted development, as well as the first evidence of its use in Ukraine.

A novelty of the LMUR, compared to Russia’s other helicopter-launched anti-tank missiles, is a two-way datalink connecting the missile to the helicopter. The missile flies to the target area guided by inertial autopilot with course correction provided by the satellite navigation system. Once close to the target, the image from the missile’s thermal-imaging seeker is transmitted to the helicopter operator’s cockpit by the datalink, and guidance commands are transmitted back to the missile. The operator can select a target for the missile. To communicate with the missile, the helicopter uses the AS-BPLA system. In the Mi-28NM, its antenna is built into the top of the front fuselage, while the Ka-52M carries it in a teardrop-shaped pod suspended under the left wing.

The LMUR, with a weight of 231 pounds including a 55-pound warhead, is twice as heavy as typical Russian helicopter-launched anti-tank missiles. Its range is also twice that of other Russian anti-tank missiles.

Theoretically, a single Mi-28NM could carry eight LMUR missiles on four APU-L twin launchers, but it’s hard to imagine that the weapon system operator would actually have time to guide such a large number of missiles in a single sortie. In most available imagery we see helicopters armed with two missiles.

While much about the advanced Mi-28NM version — and especially its production and service use — remains obscure, this latest imagery makes it clear that it’s playing an important role in the war in Ukraine. The Mi-28NM may well not be the only aerial platform now using the new LMUR missile in the conflict (the Mi-8MNP-2 special forces helicopter is another likely candidate), but it seems likely that the results of these engagements involving the Havoc will be critical for the future of this weapon.

Looking further to the future, with the Mi-28NM still competing with the Ka-52M for orders from Moscow and from export customers, it could also be the case that the relatively heavy losses inflicted on the fleet of Kamov attack helicopters could boost the chances of follow-on orders for the latest iteration of the Havoc.

Piotr Butowski is a leading expert on Russian aviation. Since the late 1970s, he’s written 30 books and published thousands of articles in aviation magazines all over the world.

Contact the editor: thomas@thedrive.com