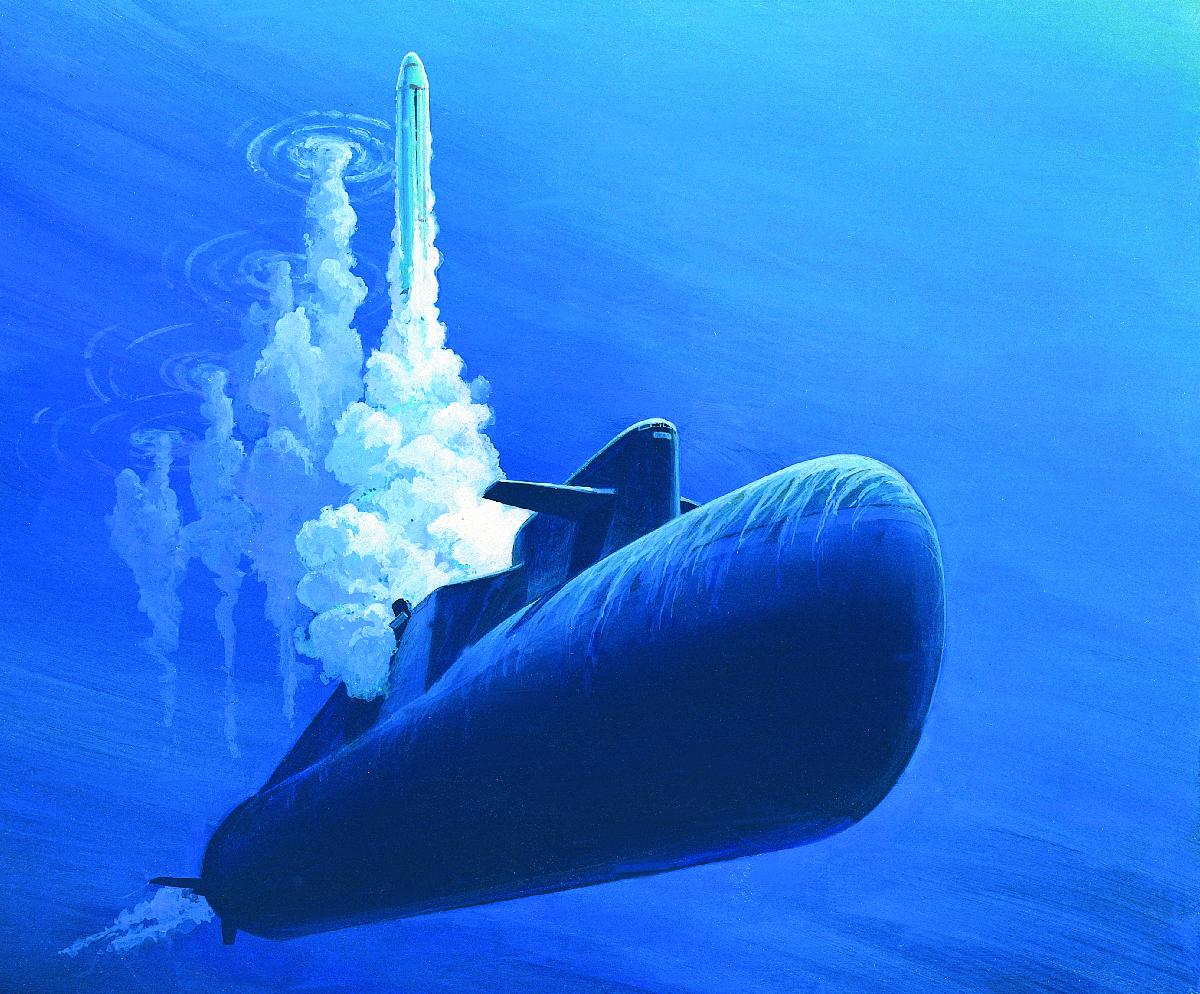

In the final years of the Cold War, the Soviet Navy tasked two of its Delta class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, or SSBNs, to verify their capability to launch a full salvo of 16 ballistic missiles at once. This was Operation Behemoth, and the results were, it has to be said, mixed.

The first attempt in 1989 ended in disaster when propellant and oxidizer leaked from one of the missiles and ignited in the launch tube; the resulting explosion destroyed the missile. The second test, however, carried out in 1991 by another Delta class submarine, was successful — for the first time ever in naval history a full ballistic missile salvo launch was made from a submerged submarine.

Perestroika and the end of the Cold War

Beginning in late 1969 the Soviet Union and the United States held a series of negotiations to limit the capabilities and number of nuclear weapons that they fielded, known as the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, or SALT I and SALT II. In the early 1980s, U.S. President Ronald Reagan announced another round of negotiations, under the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START. The focus was on further limiting the number of nuclear warheads and hence their carriers: the submarines, ground-based missiles, and strategic bombers that formed the so-called nuclear triad.

Negotiations were complicated, with many postponements, but in the mid 1980s an outline of an agreement started to take shape. In 1985 the final leader of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, was elected as general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Gorbachev began to introduce his famous policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) into the daily life of millions of Soviets. These measures increased freedom of speech, made efforts to democratize the political system, and reconstructed a rigid economic system into a more flexible and partially decentralized model.

The Soviet Union’s armed forces didn’t share much of Gorbachev’s enthusiasm for change. The only possible outcome of the START treaty, once signed, would be fewer nuclear warheads and fewer carriers for them. The leaders of the services responsible for the nuclear triad (Navy, Air Force, and Ground Forces) were unaware of the exact details of the limitation talks and could only guess as to the scale of their impact on the future of the armed forces.

To show their strength and determination — and the potential danger of any START limitations — the Soviet Navy came up with an idea to demonstrate its deterrence capability. This would involve launching a full ballistic missile salvo from a submerged submarine — showcasing the first, or perhaps the last act in the event of a nuclear war.

Delta class: backbone of the Russian Navy’s nuclear deterrent

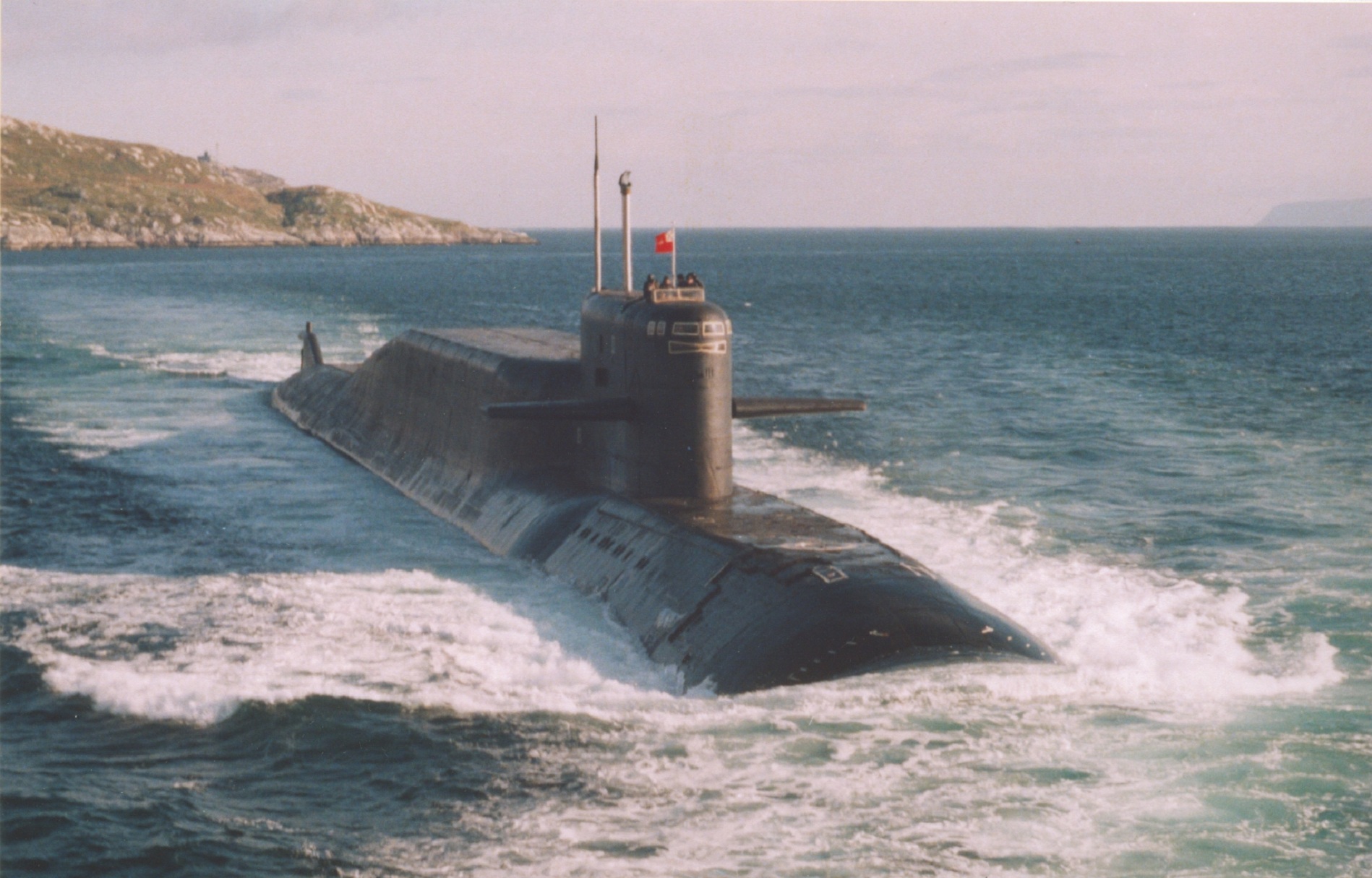

Armed with 12 and later 16 submarine-launched ballistic missiles, or SLBMs, the Delta class SSBNs formed the core of the Soviet, and later the Russian Navy’s, nuclear deterrent.

The Delta class submarines were based on the earlier Project 667A Navaga and Project 667AU Nalim SSBNs, both of which were known to NATO as the Yankee class. They had much in common, including the same engine room layout, for example. Since their introduction in 1973, four different Delta variants were produced over the course of the next three decades:

- Project 667B Murena, NATO Delta I class, 18 submarines in total

- Project 667BD Murena-M, NATO Delta II class, 4 submarines in total

- Project 667BDR Kalmar, NATO Delta III class, 14 submarines in total

- Project 667BDRM Delfin, NATO Delta IV class, 7 submarines in total

All four Delta variants were developed by the famous Rubin design bureau in Saint Petersburg. Each new generation carried larger and heavier SLBMs; in the process, the massive ‘turtleback’ missile compartment grew bigger. The electronic equipment also evolved over the years, as did the sound-absorbing solutions applied to the noise-generating machinery.

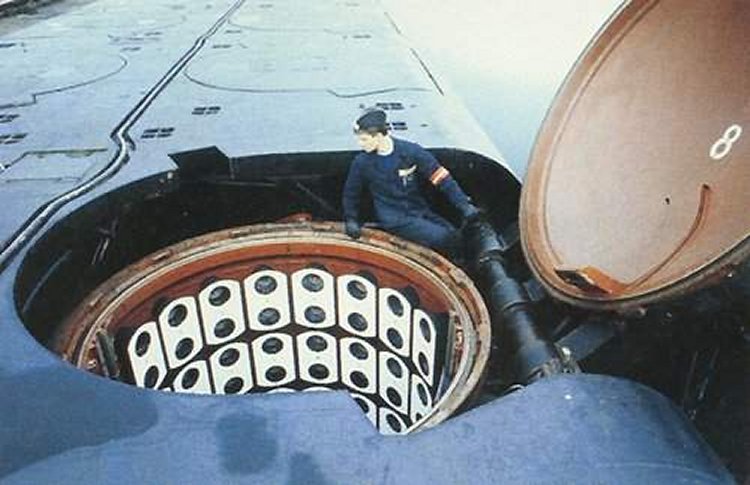

All Delta class submarines were powered by two nuclear reactors generating steam for two turbines that drove two propeller shafts allowing a maximum submerged speed of around 25 knots. The main armament consisted of 12, and later 16 SLBMs from the R-29 family. For self-defense, the designers included six, and later four torpedo tubes able to launch a wide variety of torpedoes, anti-submarine guided missiles, and torpedo decoys. Maximum diving depth was approximately 400 meters (1,300 feet) and the endurance was usually 90 days for a crew complement of between 120 and 135. All Delta class variants were built to be able to surface through the Arctic ice if needed.

The first attempt: incomplete salvo

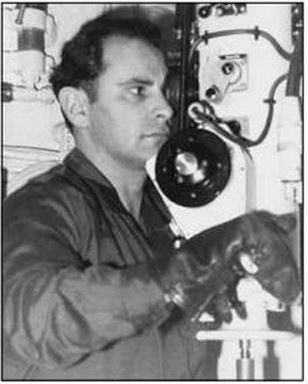

The first Soviet submarine to try a ballistic missile salvo launch was the Project 667A or Yankee class SSBN K-140. In late 1969, the commander of K-140, Captain 2nd rank Yuri Beketov, was given the task to prepare his crew for the launch of eight R-27 Zyb (SS-N-6 Serb) SLBMs out of the total of 16 carried. The reason for a limited salvo of just eight missiles was that these had already been prepared for a simulated launch during a previous patrol, meaning that the service life of the missiles was significantly reduced and that they had to be either launched or replaced in less than three months. The commander was given two months for preparation; the crew spent days and nights training.

Finally, on December 18, 1969, K-140 was put out to sea with 16 honorable guests on board, including V. P. Makayev, the chief designer of the R-27 Zyb SLBM. After arriving at the selected exercise area, within sight of the shore, K-140 submerged to periscope depth to begin preparations for the launch. After completing all pre-launch checks, the submarine dived to the launch depth of around 160 feet (50 meters), commenced hovering at a speed of 3.5 knots, and the commander gave orders to pressurize the first four missiles. At approximately 08:30 A.M. the weapon control system confirmed launch readiness, four hatches slowly opened, and the first missile was launched, followed in seven-second intervals by the second, third, and fourth. The initial salvo took one and a half minutes to complete, and all missiles were now following their pre-programmed trajectory.

Immediately after the fourth missile left the tube, the crew noticed that K-140 was slowly diving below the designated launch depth, thought to be an effect of the massive change in the trim. To compensate for the change, the commander ordered a slight speed increase, and after returning to the launch depth the next four missiles were launched successfully. Beketov was later awarded the Order of the Red Banner and K-140 became the first submarine ever to launch an eight-missile salvo.

Yuri Beketov’s naval career continued until 1991 when he retired as a rear admiral after which he lived in Moscow until his death in 2015.

Operation Behemoth-1: Failed attempt

K-140’s success was greatly appreciated by Soviet Navy officials, however, there was still an open question of whether a submarine could launch a full load of missiles safely; the partial salvo fired by K-140 simply wasn’t enough. It took the next two decades to come up with a plan and a platform for another test.

Starting in the mid 1980s, new Project 667BDRM Delfin or Delta IV class SSBNs were commissioned into service. The Delta IV was the final iteration of the Project 667 Yankee/Delta family of submarines. It was armed with 16 R-29RM Shtil (SS-N-23 Skiff) SSBNs, later replaced by the R-29RMU2 Sineva (SS-N-23A Skiff).

On August 6, 1989, in the White Sea training area, the Delta IV class SSBN Ekaterinburg (K-84) made the first attempt to launch a full salvo of all 16 missiles in Operation Behemoth-1 (the Russian word Бегемот, or Begemot, actually means hippopotamus). Apart from the regular crew members, an additional 50 high-ranking Soviet naval officers were onboard to observe the launch; their presence greatly increased the pressure on the regular crew.

There are various and conflicting accounts about exactly what happened next and when. According to one account, just a few minutes before the beginning of the test, a massive explosion rocked the submarine. With propellant and oxidizing agent leaking from the missile in the no. 6 tube, the resulting explosion destroyed the missile. The massive over-pressure generated by the explosion contained in a tight space tore off the tube hatch and shot it high above the missile compartment. The hatch, weighing many hundred pounds, flew over the sail of the submarine and landed on the bow where it pierced the main ballast tank.

Another account reports that the explosion occurred during the process of launching the second missile. According to Captain Igor Kurdin, Ekaterinburg’s commander between 1990 and 1993, the automatic launch sequence failed at the very beginning of the test. The crew attempted to bypass the automation and launch the missiles manually, but this ultimately led to a complete cancellation of the launch sequence followed by the explosion just seconds later. The damaged missile was partially ejected from the tube and the test had to be called off immediately.

Kurdin remembers the immense impact of the failure on the morale of the crew. Their actions and performance were very closely observed by the high-ranking Soviet Navy officers who had expected to witness a problem-free salvo.

The exact details of the test remain unclear even today, however, there are a few eyewitness reports about the actions of Ekaterinburg’s crew immediately after the explosion. At the time of the accident, 23 people were present in compartment no. 4 (the missile compartment). Six sailors remained at their stations, while the others were evacuated to the aft compartments.

The explosion damaged multiple hydraulic circuits and the leaking fluid short-circuited the lighting system and electric switchboards. The control room decided to switch off all electricity in compartment no. 4 to eliminate the risk of additional fires, but now the emergency lighting system also malfunctioned after being shorted-out by the leaking hydraulic fluid.

The six sailors that volunteered to remain in the compartment worked almost in complete darkness to save the boat. First, they manually opened a series of valves to flood the damaged missile tube with seawater and extinguish the raging fire. Extremely toxic fumes from the missile’s oxidizer (nitrogen tetroxide) began to leak into the compartment, forcing the crew to use their regenerative breathing apparatuses; the stock of these was very limited, as some of the evacuated sailors had grabbed a number of the replacement cartridges on their way out of compartment no. 4.

The emergency actions continued for another exhausting 24 hours. The boat was finally able to surface and the whole compartment and the rest of the boat were fully ventilated. Safety precautions were still in place for another two missiles closest to the damaged tube and the crew fully drained the oxidizer from both of those SLBMs to prevent another disastrous event.

After reporting this major accident to the headquarters, the crew of Ekaterinburg was told not to enter the White Sea Naval Base due to the unknown level of contamination from the leaked rocket fuel and oxidizer. Instead, the submarine was ordered to attempt to launch a salvo of the remaining missiles. The crew submerged the boat and configured it for launch, but the system failed again and didn’t launch a single missile.

The next idea radioed from base was to try to launch the missiles while surfaced in salvos of four. The exhausted crew once again prepared the boat for a test, but yet again the launch system failed completely and not a single missile was launched.

Only after all these futile and extremely dangerous attempts had been made, the headquarters finally allowed the stricken Ekaterinburg to return to the base for decontamination, investigation, and repairs.

Commander Igor Kurdin, now aged 70, retired from military service in 1994 and gives occasional interviews about the issues faced by the current Russian submarine force. He also wrote and co-authored books about the loss of submarines K-219 and Kursk (K-141).

Operation Behemoth-2: A farewell salute to a dying empire

The embarrassing failure of Operation Behemoth-1 greatly increased the pressure on the Soviet Navy, which was now desperate to show its ability to deliver a devastating nuclear strike. Preparations for the next attempt began very shortly after Ekaterinburg’s failure.

To carry out Operation Behemoth-2, Vladimir Chernavin, commander-in-chief of the Soviet Navy, chose the latest Delta IV class submarine Novomoskovsk (K-407), commanded by Captain 2nd rank Sergey Egorov. Egorov’s crew spent more than a year in various simulators and went out to sea five times to test the readiness of the boat.

Launching all 16 R-29RM Shtil missiles in one salvo requires an extremely well-trained crew to keep the submarine hovering at the launch depth, maintaining perfect trim and constant speed; these parameters are immediately affected by even a single missile release. Every missile hatch that’s opened generates additional hydrodynamic drag on the submarine, slowing it down. To get the speed back into the very narrow margin for a missile launch, the engine room crew must carefully increase the propeller rotations. Prior to the launch, all 16 missile tubes are flooded with seawater, adding hundreds of tons of additional weight that must be compensated with careful trimming of the ballast tanks; otherwise, the submarine may sink below the launch depth.

As all the parameters are monitored by the onboard launch computer, any deviation of the depth, speed, or submarine angle may result in the automatic termination of the launch sequence. Depending on when the cancel order is given it is possible to restart the sequence, but a few seconds before the launch, specific devices in the missile go into irreversible mode and cannot be reset by the automation or the crew. The only option then is to return to port and replace the missile — and that’s exactly what Captain Egorov was trying to avoid.

After months of grueling trials, Novomoskovsk and its crew were finally ready for the ultimate test of their capabilities. The submarine went through the final series of checks, began loading the missiles, and Commander Egorov reported full readiness for the test to the Fleet Commander.

Novomoskovsk was put out to sea in early August 1991. As with the previous test, the actions of the crew were closely watched by an entourage of high-ranking Soviet Navy officials — notably Rear Admiral L. Salkov, Division Commander V. Makaev, Delta class lead designer S. Kovalev, and missile designer I. Velichko. Everyone onboard remembered the humiliating failure of Operation Behemoth-1; there was now huge pressure not to fail again.

On the evening of August 6, 1991, Novomoskovsk was hovering at a depth of around 160 feet (50 meters) within the designated launch position in the Barents Sea. The crew configured all the onboard systems for launch and anxiously waited for a signal to begin firing the first missile.

Approximately 30 minutes before the launch the submarine lost contact with the monitoring ship stationed nearby. According to the plans, a two-way communication line was necessary for the test, however, Rear Admiral Salnikov gave the order to continue. Finally, at 9:07 P.M., after receiving permission to launch, Capt. Egorov ordered his crew to launch all 16 missiles.

One after the other, in 10-second intervals, a full salvo of some of the most destructive weapons ever made emerged from the cold dark depths of the Barents Sea and began their flight along the pre-programmed path.

Apart from the submarine and monitoring ship crew, the only other witnesses to this spectacular event were the operators of the U.S. ballistic missile early warning system. Within approximately two minutes, their radar screens were tracking 16 separate dots. Their computers began calculating the trajectory of each single one: almost certainly a very tense moment. Calculations quickly showed that the first and the last missiles were heading towards the Kura missile testing range in Kamchatka in the Russian Far East; these were the only two missiles equipped with unarmed reentry vehicle warheads, the other 14 SLBMs were set to self-destruct upon reaching the maximum altitude.

Operation Behemoth-2 was a complete success. Capt. Egorov was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union and promoted to Captain 1st rank on the spot by Rear Admiral Salnikov.

But the Soviet Union was destined to last just two more weeks and once it collapsed, all the medals and awards were swiftly forgotten; Egorov’s award was reduced to the Order of the Red Star. Unknowingly, he and the crew of Novomoskovsk had given the dying empire a powerful farewell salute.

After dismissal from military service, Sergey Egorov worked in Saint Petersburg, where he died on August 28, 2007, aged 52.

Aftermath and the dawn of a new threat

The collapse of the Soviet Union marked the end of the bipolar world and heralded the end of the Cold War. Former enemies divided by the Iron Curtain and opposing ideologies slowly began to cooperate and build mutual trust.

The Russian military suffered heavily in the next decade; a period dubbed ‘the wild 90s.’ The old Soviet leadership principles were gone and a new Russian ones were yet to be formed.

Massively underfunded, all branches of Russia’s military suffered from widespread theft, complacency, and ignorance. The Russian Navy was hit enormously. Ships and submarines were abandoned to rot at their piers; crewmembers were not paid for several months; equipment was cannibalized to keep at least a few assets seaworthy.

The desperate situation and the overall lack of proper command were made fully clear in the tragic loss of the Project 949A Antey or Oscar II class nuclear-powered, guided-missile submarine Kursk (K-141) on August 12, 2000. Reluctance to accept help from NATO nations to rescue the sailors, lack of communication between the higher echelons complicating the rescue efforts, and the extremely poor reactions to the public outcry showed how badly managed the Russian Navy really was.

Ultimately, the Russian leadership learned from these bitter lessons and started to increase the Navy’s budget. Old facilities were upgraded, design offices active during the Soviet era sharpened their pencils again, and a new Russian Navy began to take shape.

The process of decommissioning the oldest Delta class submarines began in 1989 and continues to this day. Currently, only a handful of Delta III and Delta IV class submarines remain on active duty — one of them is Novomoskovsk, still with the Northern Fleet. They are gradually being replaced by the newer Project 955 Borey and Project 955A Borey-A SSBNs, known to NATO as the Borei I and Borei II, respectively.

The invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 shattered all hopes of peaceful cooperation with the current Russian leadership. The shadow of a new Cold War is instead emerging and once again we’re witnessing nuclear saber-rattling. For the Russian Navy, the two most prominent examples of this in recent months are the claims that the first production examples of the Poseidon nuclear-powered, nuclear-tipped torpedoes have been built, and the announcement that the Zircon hypersonic cruise missile has begun its first deployment, arming the Project 22350 frigate Admiral Gorshkov.

At the same time, the Russian Navy’s SSBN force remains very much active as a critical component of its nuclear deterrent.

In the end, Operation Behemoth-2 proved beyond any doubt the ability of a submarine to deliver a devastating attack in what can truly be described as a dress rehearsal for the nuclear apocalypse.

About the author: Matus Smutny is a Senior Lead Engineer in the automotive industry and has a lifelong passion for post-war naval history and technology. He maintains a digital gallery containing more than 137,000 photos and can be found on Twitter as @Saturnax1 .

Contact the editor: thomas@thedrive.com