Russian state media outlets have offered unprecedented looks at the payload bus for the R-36M2 intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM, where the weapon’s nuclear warheads are housed. Also known as the SS-18 Mod 5 Satan in the West, this missile has a so-called multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle, or MIRV, configuration and has one of the heaviest payloads of any ICBM ever developed and fielded.

Dmitry Kornev, a Russian military expert who runs the blog Military Russia, recently posted stills showing the R-36M2 payload bus on Twitter that were captured from video clips broadcast on the state-run television stations Russia-24 and TV Zvezda. The latter of these is the official television station of the Russian Ministry of Defense. Kornev indicated that the footage has been shown after the first full-scale launch of the RS-28 Sarmat ICBM in April 2022. The RS-28 is expected to eventually replace the R-36M2 in Russian service.

The R-36M2 is a two-stage (not including the payload bus) liquid-fueled silo-launched ICBM the Soviet Union first started developing in the early 1980s as a more accurate and otherwise more capable successor to earlier R-36M variants. The original R-36M had begun replacing older R-36-series missiles in the 1970s. One of the biggest differences between the R-36M and the R-36, also known in the West as the SS-9 Scarp, was the change in the newer design to a cold launch system that uses a gas generator to eject the missile from the silo before its main rocket motors ignite.

Often referred to as a heavyweight ICBM, the R-36M2 is massive, with an overall length of around 112 feet (37.25) meters, nearly 10 feet in diameter (3 meters), and weighing just over 211 tons with a full load of fuel, according to the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). By comparison, the U.S. Air Force’s LGM-30G Minuteman III is just shy of 60 feet (18.3 m) long, is five and a half feet (1.67 meters) wide, and is just under 40 tons when launched. The larger LGM-118A Peacekeeper, which the U.S. Air Force withdrew from service in 2005, was still substantially smaller, with a length of some 69 feet (21.1 meters), a diameter of just over seven and a half feet (2.34 meters), and a launch weight of close to 98 tons.

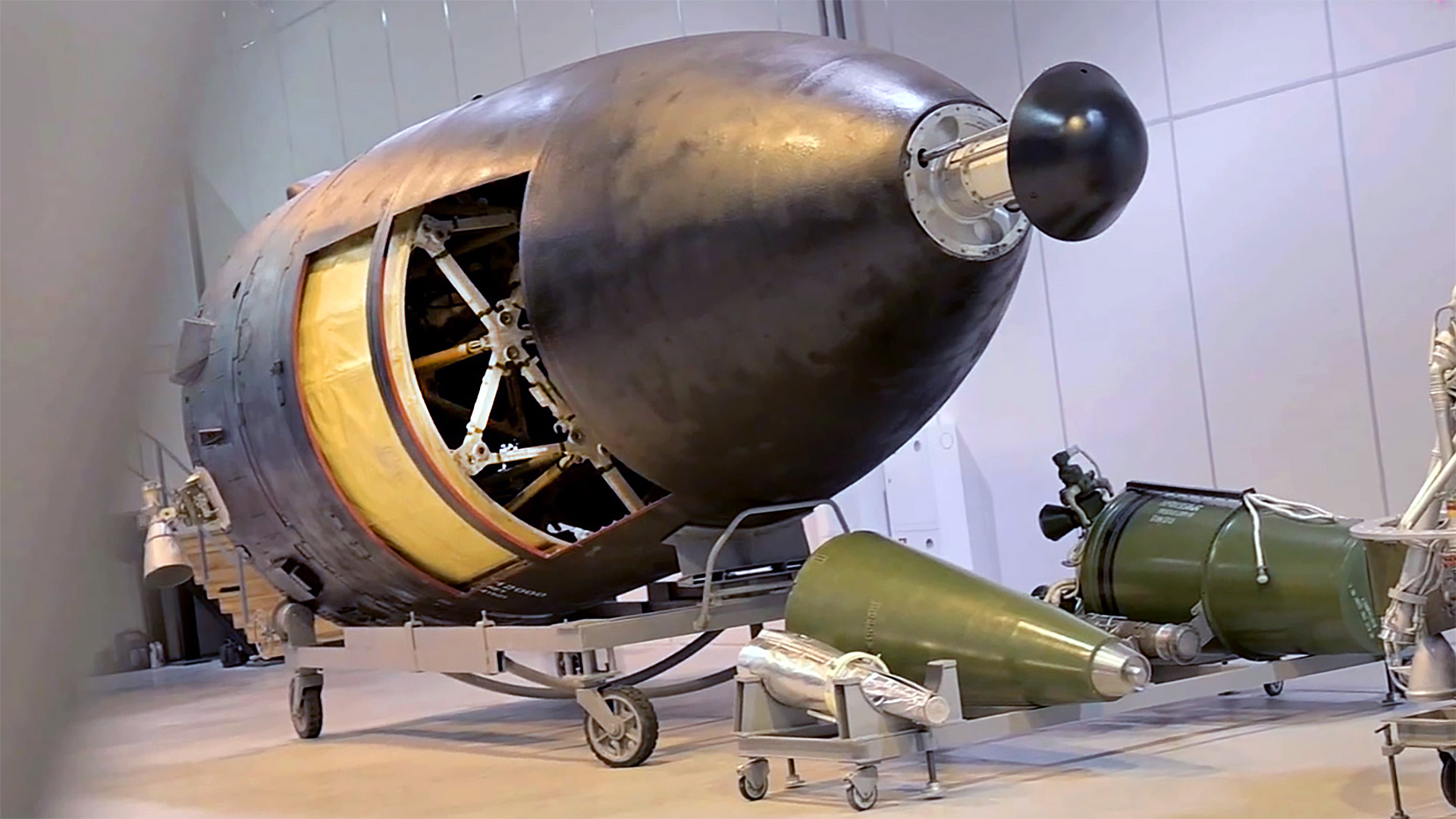

The images that Kornev shared online immediately underscore just how big the R-36M2 is by showing the size of the payload bus by itself. The bus can carry up to 14 warheads, in two rows of 7. There is disagreement about the approximate yield of these warheads, with many sources saying they are in the 550-750 kiloton range, while some others suggest they could be more powerful, between 750 kilotons and one megaton.

Regardless, each of these missiles is typically loaded with 10 warheads, according to Kornev. The other four slots are instead filled with what are known as penetration aids, which are decoys and other devices intended to make it difficult for enemy forces to determine which of the incoming objects are real threats, track them, and potentially attempt to intercept them.

Some of the stills that Kornev shared on Twitter show what appear to be decoys, or at least mock-ups thereof, among other things in front of the bus.

The images also look to show four independent rocket motors at the rear of the bus, which would be used to position it in space before releasing its warheads and penetration aids over multiple targets along a set path.

The U.S. Air Force video below gives a good general look at how the payload bus on a typical MIRVed ICBM, loaded with a mixture of warheads and penetration, functions.

Lastly, the images of the R-36M2’s payload bus highlight a particularly curious feature at the tip of the nosecone. At first glance, this would appear to possibly be a drag-reducing aerospike similar in broad strokes to those used on the U.S. Navy’s Trident series of submarine-launched ballistic missiles. On those weapons, which have very blunt nose cones designed to provide greater internal volume without having to increase overall length, the aerospikes help reduce drag during launch.

However, Kornev says that this protrusion on the Russian missile is actually part of the system for removing the nose cone from the rest of the payload bus so the warheads and penetration aids can be released.

Why the Russians have decided to publicly show off these details about the R-36M2 is unclear. While these missiles are set to be replaced entirely, it’s not known exactly when their successor, the RS-28 Sarmat, which the West calls the SS-X-30 Satan 2, will actually begin to enter service. The original plan was for those new ICBMs to start being loaded into silos last year, something that obviously did not come to pass. There were delays in the development of the RS-28 even before Russia launched its all-out invasion of Ukraine in February, which has led to crippling international sanctions and other strains on the country’s defense industrial base. There have been reports that the Kremlin has scrapped its most recent long-term defense spending plans over the conflict.

The video below shows a more limited test of the RS-28 design prior to the full-scale test in April.

Whatever the case, we have now gotten an unusually good look at one of the most critical parts of the R-36M2, one of the largest in-service ICBMs in the world and that looks set to be a key component of Russia’s nuclear deterrent capabilities for years to come.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com