Ukrainian officials are claiming the destruction of the first example of an Iran-supplied drone used by Russia in the war in Ukraine. The assertion is backed up by photos showing the apparent remains of what looks very much like an Iranian Shahed-136 loitering munition, or ‘suicide’ drone, reportedly found in eastern Ukraine. This appears to confirm that Iranian-made drones have not only been delivered to Russia but are now being employed in combat, including in strike missions.

According to a statement on the Armed Forces of Ukraine’s Strategic Communications Telegram channel, the drone in question is a “Shahed-136 long-range kamikaze UAV,” which is said to have been destroyed by Ukrainian air defenses near Kupyansk, in the eastern Kharkiv region.

“Analysis of the appearance of the elements of the drone’s wing allows us to confidently state that the Armed Forces of Ukraine destroyed an Iranian UAV for the first time,” the statement adds.

The Telegram post is accompanied by the same images of apparent drone wreckage that have also appeared on social media, including on the official channel for the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense. The remains undoubtedly look very much like the Shahed-136 series. The vertical stabilizer from the end of one of the drone’s delta wings seen in some of the pictures is a particularly distinctive feature of the Shahed-136 and other related Iranian designs.

Interestingly, it appears that Russia has named this drone Geran-2, meaning ‘geranium-2.’ This would be in keeping with the Russian tradition of naming artillery after flowers. This could further indicate that the drones are indeed being used as munitions, fitted with warheads, to attack Ukrainian targets on the ground, rather than other roles like surveillance or acting as decoys.

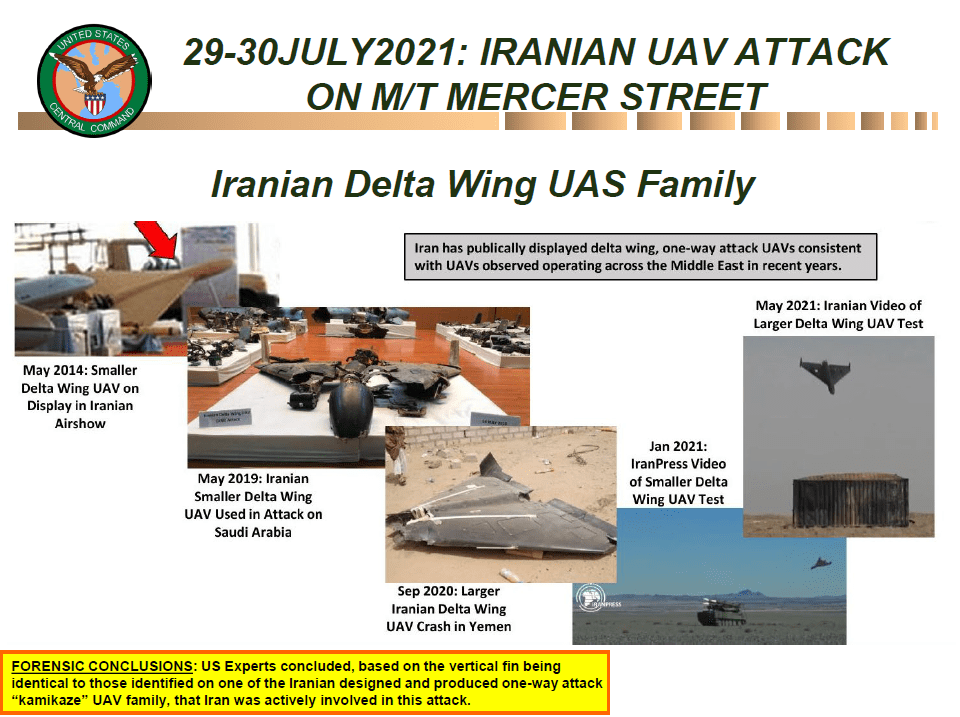

As for the Shahed-136, this is one member from a family of designs dating back to around 2014, and which as well as being in widespread Iranian service have also been transferred to Iranian proxies, such as those operating in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen.

At the same time, this could make drones like these well suited to more rapid export in more conventional contexts like Russia’s war in Ukraine.

While the first appearance of Iranian-made drones in combat happened relatively soon after news of Tehran’s potential UAV transfer first broke, it’s more or less in keeping with previous reports, based on U.S. intelligence, which indicated that Iran was preparing to train Russian forces to use these drones “as soon as early July.”

When the first reports emerged of transfers of potentially “hundreds” of Iranian drones to Russia, there was much speculation that these could be larger armed designs: essentially, UAVs that can carry disposable armament as well as targeting sensors and which can return to base after their mission. But as The War Zone pointed out at the time, one-way loitering munitions like the Shahed-136 would also be very useful for Russia in its war in Ukraine and would certainly be procured alongside reusable systems.

All in all, it should not come as a great surprise that the first Iranian-made UAVs that appeared in this conflict are loitering munitions. Iranian-made suicide drones have become a notable feature of raids launched by Iran and its proxies in the Middle East. In recent months, their use in targeting critical infrastructure, including oil, in Saudi Arabia, has been noteworthy, but the use of suicide drones by Iranian proxies dates back at least to 2017 when they were employed against Patriot batteries in Yemen.

In the hands of Iranian and Iranian proxy forces, the Shahed series, in particular, has also been used for high-profile attacks in a maritime environment, such as the fatal drone attack on the Liberian-flagged, Israeli-operated tanker, M/T Mercer Street, off the coast of Oman, in August last year.

These weapons could now help Russia as it grapples with Ukrainian ground-based air defense systems that have proven very effective in limiting the kinds of operations that the Russian Aerospace Forces have been able to conduct anywhere beyond the front lines. Overall, the difficulties Russian aircraft have had in the suppression/destruction of enemy air defenses (SEAD/DEAD) role has been a key factor in the air war, and one that the availability of long-range suicide drones might help address. For this mission, a passive radar seeker would allow autonomous attacks, of the kind pioneered by the Israeli Harpy drone. But even without a passive seeker, drones like these could be useful in simply overwhelming hostile static air defense and other targets, including those related to infrastructure, if launched in the required numbers. While small in size and slow, these drones have remarkable range and could hit targets hundreds of miles away.

As such, armed drones like the Shahed-136 would also provide Russia with an alternative means of carrying out strikes against higher-value targets located deeper in Ukraine. These kinds of raids are something that Ukraine has apparently been conducting to great effect, albeit under a veil of secrecy, against targets within Russia and in occupied Crimea using their own long-range suicide drones.

At the same time, depleted stocks of conventional cruise and ballistic missiles mean that Russia is badly in need of any kind of standoff offensive weapons, even comparatively short-range ones. While lacking the sophistication and destructive power of these kinds of missiles, long-range suicide munitions are far cheaper and, if procured from Iran, not affected by the sanctions that are hindering Russia’s ability to produce its own precision strike weapons.

There is also the possibility that Russia might undertake its own, licensed production of the Shahed-136, and perhaps other Iranian-designed drones, too. Indeed, the fact that the drone wreckage displays a Russian name could suggest that plan is already in the works, or it may be an effort to conceal the origin of the Iranian-made drones. This would not be entirely dissimilar to how Iran conducts business with some of its proxies, such as the Houthis, where at least some level of domestic assembly of drones, with Iranian help, has been going on for years now.

Moreover, any kind of armed drones would help Russia keep pace in this field with the Ukrainian Armed Forces, which have so far taken a leading role in using unmanned aircraft as weapons in the conflict. So far, Russian drones, from domestic production, have been used mainly for surveillance, although there are also records of relatively ineffective loitering munitions having been used, too.

Overall, the complex nature of some of the drone attacks previously linked to Iran, and the vulnerability to infrastructure that they demonstrate, have repeatedly reinforced just how much of a threat such ‘low-end’ drones can present. This is also a reality that The War Zone has explored in the past.

Ultimately, the appearance of these attack drones in Russian hands is a significant one and could have several major repercussions. It provides a means for Russia to attack a range of Ukrainian targets, including en masse, over long distances, and potentially even to launch constant ‘vengeance’ strikes on heavily populated areas that are situated a measurable distance from the front lines, like Kyiv. At the same time, the delivery of these weapons from Iran could open the door to that country becoming a much more important source of weapons for Russia as it struggles to maintain weapons stocks and reassert itself on the battlefield in Ukraine.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com