Today, a fleet of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers is a central tool of American power projection, and these mighty warships and their aircraft are emblematic of the prowess of U.S. naval aviation. For a brief period in the 1930s, however, it looked as if the Navy might also field an armada of flying aircraft carriers — in the shape of giant rigid airships with their own squadrons of fighters that could be launched and retrieved in mid-air. Ninety years after trials of this concept began using the airship USS Akron, we look back on this incredible episode in naval airpower.

By the 1930s, the U.S. Navy was well-versed in aircraft operations from warships at sea, with the first generation of flattops proving that, with the help of tailhooks, aircraft could take off from warships and return to the deck after their mission. Often forgotten today is the fact that, at around the same time, the Navy was embracing the potential offered by rigid airships, inspired by the Zeppelin types that Germany had employed with considerable success in World War I.

Since an aircraft could be launched and recovered from a suitably equipped warship at sea, there was no reason why an aircraft — with a hook mounted above it, rather than below it — couldn’t also be snagged in flight by an airship, as it cruised through the clouds. That, at least, was the theory espoused by some influential Navy officers after the end of World War I.

From 1921, the Navy had five rigid airships built, one of them, the USS Los Angeles, being completed by the Zeppelin company in Germany, as part of war reparations. It was this airship that kickstarted the service’s experiments with flying aircraft carriers.

In July 1929, the USS Los Angeles conducted first-of-their-kind flight operations off the coast of New Jersey. Flying an adapted Vought UO-1 observation biplane, Lt. A. W. ‘Jake’ Gorton approached the airship from the rear, before aligning a hook mounted above his plane with a trapeze dangling below the Zeppelin. Just like a seagoing aircraft carrier, the airship turned into the wind to facilitate the operation. The whole process took six minutes.

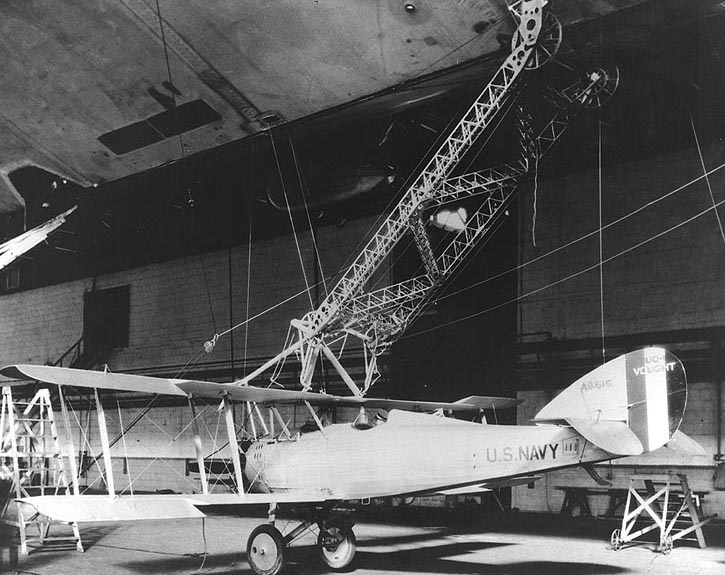

A modified Vought UO-1 observation biplane attached to the trapeze below the USS Los Angeles. San Diego Air and Space Museum Archive

While the British and the U.S. Army had previously tested operations of heavier-than-air aircraft from airships, this was a milestone for the U.S. Navy. It would also mark the beginning of the most extensive period of trials of this concept to ever be conducted.

A Vought UO-1 attached to the trapeze during mating experiments with the USS Los Angeles in the airship hangar at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, in December 1928. U.S. Naval Historical Center

The USS Los Angeles was always intended to be used as an aircraft-carrying airship in an experimental capacity. By the time Lt. Gorton had proved the idea, the service had already ordered a pair of new airships, ZRS-4 and ZRS-5, which would become the USS Akron and Macon, respectively. From the start, these airships would include a hangar area, measuring 75 feet by 60 feet and located aft of the control car. Maneuvered on the trapeze, aircraft could enter the hangar via a T-shaped door below it.

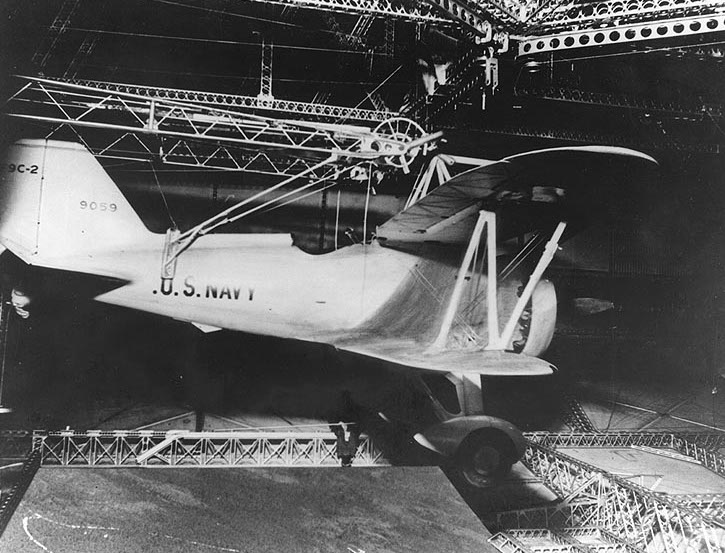

The dimensions of this door dictated the size of aircraft that the new airships would be able to operate. The choice ultimately fell upon the Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk biplane, which had been designed as a carrier-based fighter. The diminutive proportions of the aircraft meant it was a good match to the airships’ hangars, each of which could accommodate a maximum of five Sparrowhawks, although three was a normal load for Akron and four for Macon.

The Sparrowhawk also had some advanced features, for its time, including all-metal semi-monocoque fuselage construction and aluminum-alloy wing spars. It was powered by a 420-horsepower Wright R-975C engine, had a top speed of 176 miles per hour, and could climb to a height of 22,600 feet. The prototype XF9C-1 made its maiden flight at Long Island in February 1931.

Navy trials of the F9C were not altogether satisfactory. Issues identified by the test team included poor pilot vision from the cockpit and overall performance that lagged somewhat behind its competitors at the time. However, the dimensions of the Curtiss fighter ensured that, in July 1931, it was picked by the Navy to operate from its two new rigid airships, USS Akron and Macon.

In the meantime, the Navy had begun to put together a pilot cadre to operate the new fighters from their airships, with aviators arriving with the Heavier-than-Air Unit at Naval Air Station Lakehurst early in 1931.

For training, they made use of a specially equipped Fleet N2Y and used the trapeze that was already fitted to USS Los Angeles. For the pilots, used to recovering on pitching and rolling carrier decks, the process of catching the trapeze was, if anything, less complex, providing the weather was fine.

By the fall of 1931, series-production F9C-2 aircraft had begun to arrive, and on October 27, the USS Akron was commissioned into service. At first, however, the airship had to undergo extensive trials with the fleet at sea.

While USS Akron was put through its paces, an expanding pilot cadre at the Heavier-than-Air Unit now had the prototype XF9C-1 and seven F9C-2s to work with. “It was a beautiful little biplane to fly, even though it required constant attention,” recalled one of the pilots, Lt. (jg) Harold B. Miller.

Working with the USS Los Angeles, the pilots established the operating procedures for trapeze operations. The altitude minimum was 800 feet and the airship had to be moving at 68-70 knots or more, to avoid the fighter stalling.

Thanks to a spring-loaded mechanism on the fighter’s hook, the pilot only needed to contact the trapeze bar and their aircraft would be locked on. That was the theory, but in practice, there were times when pilots thought they had achieved contact with enough force to make a firm connection, only for them to feel their aircraft fall away. If that happened, it was a case of dropping the nose, gaining speed, and returning for another go.

It was also vital that the pilot make contact in the mid-point of the trapeze bar, otherwise the Sparrowhawk would not be able to pass through the hangar’s T-shaped door. Clearance at each wingtip was just four inches. Ultimately, a drop-down brace was introduced to guide the fighter through the aperture.

So much for the practicalities of flying from the trapeze. At the same time, pilots were developing tactics for how to actually use the airship/fighter combination operationally. The Heavier-than-Air Unit proposed that the fighters would be best used for long-range aerial scouting, spotting enemy aircraft for the protection of the airship, which could then take evasive action. Engaging enemy aircraft with its twin 30-caliber machine guns was considered a secondary mission, mainly due to the limited performance of the Sparrowhawk.

On May 3, 1932, the USS Akron undertook its first parasite fighter trials with the Sparrowhawk. On that occasion, Lt. Howard L. Young was at the controls of the prototype XF9C-1.

Lt. Howard L. Young in the cockpit of the XF9C-1 Sparrowhawk as the fighter is lifted into the hangar of USS Akron, May 3, 1932. U.S. National Archives

On rare occasions, the Heavier-than-Air Unit took its Sparrowhawks to operate from conventional aircraft carriers, where the aircraft’s inverted hooks and garish “Men on the Flying Trapeze” insignia must surely have attracted much interest among the deck crew.

The project was dealt a major blow on the night of April 3-4, 1933, when the USS Akron was lost in a storm off the New Jersey coast, together with 73 crewmen. Among the dead was one of the chief proponents of the airship-fighter concept, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics.

The sister airship, USS Macon, was commissioned in June 1933 and soon began exercises from its base at Sunnyvale, California. However, its showing in these war games was disappointing, with repeated simulated ‘kills’ scored against it. If anything, this demonstrated that the Sparrowhawks were urgently required for the scouting role to offer the airship some level of warning against aerial attack.

This role brought up the challenge of communications between the fighter pilots and their airship. It required the development of new radios as well as tactics that would best exploit the Sparrowhawk’s radius of action and increase the sector over which it would be able to patrol while beyond visual range. The addition of a low-frequency radio direction-finder to the F9C allowed the fighters to roam even further and be sure that they could find their way back to their ‘mothership,’ providing them with a basic homing device.

Another positive development was the addition of an auxiliary fuel tank for the Sparrowhawk, for a 50 percent improvement in range. This was combined with the removal of the wheeled landing gear when involved in airship operations. In case the pilot had to ditch at sea, the aircraft was provided with flotation bags under the upper mainplane, inflated using compressed gas.

During 1934-35, the USS Macon was operating off the west coast, including testing out a new mission for the Sparrowhawk in July 1934. On this occasion, the airship and its fighters were tasked with tracking down the cruisers USS New Orleans and USS Houston, after ranging far out into the Pacific. The warships, which were sailing from Hawaii to Panama, were successfully intercepted and had newspapers and mail dropped on them by the Sparrowhawks. Significantly, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was aboard the Houston, and he responded with the message: “WELL DONE AND THANK YOU FOR THE PAPERS THE PRESIDENT 1245.”

While the proponents of the airship in the Navy continued to make the case for lighter-than-air aircraft carriers, despite criticism over their vulnerability, it was to be weather, once again, that intervened. On February 12, 1935, while operating off the California coast, the USS Macon was hit by unexpectedly strong gusts of wind. These caused one of the stabilizing fins to break up, followed by the collapse of helium cells in the rear of the airship. The crew was unable to steady it and the USS Macon plunged tail-first into the Pacific. Two of the 83 crewmen lost their lives, and four Sparrowhawks were sent to the bottom of the ocean.

The loss of both aircraft-carrying airships had killed the concept once and or all. The Navy was left with three surviving F9Cs that saw out their days on general utility duties. It was, without doubt, an ignominious end for a group of aircraft that had, only months before, been involved in some of the most cutting-edge experiments in naval aviation up to that time.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com