The head of the U.S. Missile Defense Agency, U.S. Navy Vice Adm. Jon Hill, recently provided new details on progress toward establishing vastly upgraded air and missile defenses on the highly strategic island of Guam. Requirements for the overarching system are starting to solidify, but U.S. military officials still face challenges in figuring out how to fit all the components on the island.

Vice Adm. Hill gave the update on the state of the Guam Defense System during a webcast of a live interview with Defense News‘ Jen Judson on the sidelines of the 2022 Space and Missile Defense Symposium, which ran from August 9 to 11. The Missile Defense Agency (MDA) is working with the U.S. Army and Navy on this project. Installing new air and missile defense capabilities on the island, which is a U.S. territory, is part of a broader effort to deter China across the Asia-Pacific region. The stated goal, at least in the past, has been to have at least some additional defenses in place on Guam by 2026.

Guam is home to critical air and naval facilities, and is currently seeing a significant expansion of its military infrastructure, in part in order to better serve as a launch pad for Marines in the region, and would be a major target in any large-scale fight in the Indo-Pacific. MDA director Vice Adm. Hill noted in his chat last week that the island now faces an “evolved threat,” especially from China, in the form of increasingly advanced ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as new hypersonic weapons and even potential threats from space, which could strike from multiple different vectors at once.

“So, if you look at the PB 23 budget [President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2023] submittal, you will see that there’s an MDA portion, which is the Ballistic Missile Defense capability and the hypersonic missile defense capability. And then the Army brings in cruise missile defense,” Hill explained. “And what’s great is both systems kind of have a crossover in what they can do.”

“So, the integration of those into a command suite with command and control battle management on top of it, [that] is the basic architecture,” he continued. “So you can think of a number of radars that ensure we meet the requirement, which is persistent 360-degree coverage, right, because of the evolved threat.”

“We have a very good feel for at least technically and operationally where things should go, okay, in order for it to function as a system,” the head of MDA added.

Hill made clear that the exact number and combination of interceptors, sensors, command and control nodes, and other components of the Guam Defense System has yet to be finalized. Initially, there had been talk about establishing an Aegis Ashore missile defense site on Guam, but the MDA boss revealed last year that plans were shifting toward a more novel and distributed architecture, which could include hardened underground facilities.

MDA and the Army currently provide more limited ballistic missile defense on Guam. This comes in the form of a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system battery, designed to engage certain types of ballistic missiles in the final stages of their flight. An unit equipped with the Israeli-made Iron Dome system, which manufacturer Rafael says has a demonstrated anti-cruise missile capability, had been deployed on a temporary basis to the island, but for purely test and evaluation purposes.

The THAAD program is currently managed by MDA, though all of the units equipped with these systems, including the launchers and their powerful AN/TPY-2 radars, fall under the Army. The Army also bought two Iron Dome systems as part of what was originally expected to be a larger acquisition program. The service subsequently canceled that program, ostensibly over issues integrating it into its air and missile defense ecosystem. It is now in the process of purchasing examples of Dynetics’ Enduring Shield, which uses a canisterized version of the AIM-9X Sidewinder heat-seeking air-to-air missile as its interceptor.

Adding a traditional Aegis Ashore site to Guam would have provided an additional radar and the ability to launch additional types of interceptors, including versions of the Standard Missile-3, which are capable of executing mid-course intercepts against longer-ranged ballistic missiles, and the highly capable multi-purpose SM-6. The future Glide Phase Interceptor (GPI), designed to engage incoming hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, has to be able to be fired from Navy ships using the Mk 41 Vertical Launch Systems (VLS) and therefore should also be compatible with the Arleigh Burke class destroyer derived Aegis Ashore architecture.

Whether the distributed options MDA considering replicate some or all of the Aegis Ashore capabilities, or will add substantial additional ones, is not entirely clear. The agency could also seek to deploy additional THAAD systems, possibly equipped with improved interceptors. The system’s manufacturer, Lockheed Martin, has proposed a THAAD-Extended Range (THAAD-ER) missile, which it says would have greater reach and an expanded engagement envelope, including against hypersonic threats.

On the cruise missile defense side, National Advanced Surface to Air Missile Systems (NASAMS), which the Army has a number of already, but that are deployed almost exclusively to protect Washington, D.C. and the surrounding National Capital Region, might be one option. The Army together with the Air Force has been looking to expand NASAMS’ capabilities against cruise missiles and potentially pair it with other future counter-cruise missile capabilities, including self-propelled 155mm howitzers firing hypervelocity projectiles (HVP).

The War Zone, among others, has also discussed the potential repurposing of decommissioned Navy Ticonderoga class cruisers to provide extra higher-end air and missile defenses for Guam and other surrounding areas, as you can read more about here.

There have been no public discussions, at least so far, about the possibility of adding Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) interceptors, which are large silo-launched missiles, to the island’s array of defenses.

Future Army Enduring Shield systems could very well supplant Iron Dome as an option for the cruise missile defense component. They could also provide defenses against other lower-tier aerial threats. As The War Zone highlights regularly, including about Guam specifically, the dangers posed by even relatively low-end unmanned aerial systems are real now and only likely to grow as time goes on.

Additional mobile, semi-mobile, or fixed site radars, to include more AN/TPY-2s, and other sensors will undoubtedly be part of the final Guam Defense System. The Guam Defense System could incorporate newer radars, such as the AN/SPY-7(V)1 Long Range Discrimination Radar (LRDR), or a version or derivative thereof. The U.S. military’s first fixed-site LRDR is already operational in Alaska. MDA and the U.S. Space Force are separate working to expand the U.S. military’s space-based missile defense sensing capabilities.

New command and control facilities and improved networking capabilities will be critical, too. MDA already has a number of existing and planned sensor fusion architectures that would be applicable. Given the Army’s heavy participation in the air and missile defense efforts on Guam, the service’s new Integrated Air and Missile Defense Battle Command System (IBCS), which you can read more about in this past War Zone feature, is likely to be part of the ultimate networking solution.

The video below primarily provides an overview of how MDA expects to defend against hypersonic weapons in the future, but also gives a sense of existing and planned air and missile capabilities that could be woven into the final Guam Defense System.

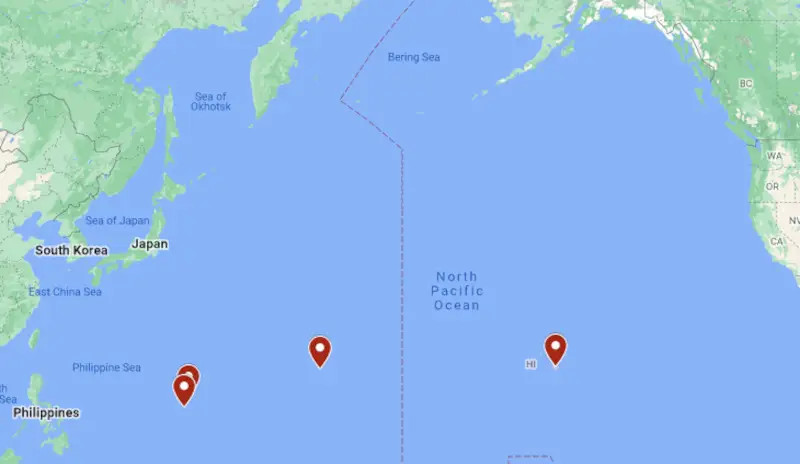

In addition, the Guam Defense System will be just one node in a larger air and missile architecture both in this particular part of the Pacific and the broader Indo-Pacific region as a whole. There are already discussions about installing a multi-mission radar in Palau, an independent archipelago nation some 805 miles to the southwest of Guam. The Pentagon has all but abandoned plans to establish a new homeland defense radar in Hawaii, thousands of miles to the east. However, there is a Congressional mandate to build something there by 2028 and the department says it is still exploring how it might meet requirements for air and missile defense sensor coverage in that part of the Pacific.

Maritime assets, especially the Navy’s ballistic missile defense-configured Arleigh Burke class destroyers, will continue to provide additional sensor and interceptor capacity. The Navy’s Ticonderoga class cruisers have missile defense capabilities, too, though it now looks increasingly like these ships are set to be decommissioned in the coming years.

On top of all of this, the U.S. military has been moving in recent years to better integrate its allies in the Pacific region into its missile defense ecosystem. As an example, the Navy recently hosted the latest iteration of the Pacific Dragon missile defense exercise, which included warships from South Korea, Japan, Australia, and Canada. This was the first time Australia and Canadian warships participated in one of these exercises and Pacific Dragon 2022 was the first to include a live interception of a surrogate for a short-range ballistic missile using an SM-3 Block IA missile.

Whatever happens, the Guam Defense System will almost certainly be highly distributed, including assets that may not even be on the island itself. Doing so can only help improve its survivability in a high-end conflict scenario, such as one involving China. The U.S. military has been very open about the potential vulnerability of the island, as a whole, in major conflict against a near-peer adversary. New airbase facilities now under construction on the nearby island of Tinian, another U.S. territory, that could be utilized if Andersen Air Base on Guam is put out of action for any reason, reflect broader U.S. military efforts to expand available basing options in the Indo-Pacific.

Just earlier this year, the Army, working in cooperation with the Air Force and the Guam National Guard, conducted a demonstration involving the deployment of a THAAD launcher from Guam some 40 miles to the northeast to Rota Island, a U.S. territory that is part of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Communications and data-sharing links were then established that would have allowed the launcher on Rota to engage threats based on targeting information from tertiary sensors, a mode of operation known as “launch-on-remote.”

This reflects a more general interest on the part of MDA and the Army in separating THAAD launchers, as well as those for Patriot surface-to-air missiles, from their associated sensor systems, and linking elements of both of those systems together, to improve their overall flexibility and survivability. In his remarks last week, Hill highlighted separate testing of Patriot launch-on-remote capabilities utilizing THAAD’s fire control architecture and targeting data from the systems AN/TPY-2 radar. Earlier this year, the final phase of those tests showed that THAAD’s command and control systems could be used directly to execute an intercept using a Patriot Advanced Capability-3 Missile Segment Enhancement (PAC-3 MSE) missile fired from a networked Patriot launcher.

“Flying a Patriot missile based on what the THAAD can see, that allows us to now see new threats and use up the full kinematic expanse of the Patriot – not have it limited to a shorter range radar,” Hill said. “So, now we can take a longer-range radar and go farther with the missile.”

Distributing the new air and missile defense capabilities on and around Guam also reflects what is the biggest hurdle that the project still has to overcome: finding places on the island to put the various new systems.

“We just finished our second, what we call a sitting summit, last week. My team was out there for a couple of weeks, met with all the major leadership out in Hawaii and on Guam, and then walked every single candidate site that’s out there,” Hill said during the Defense News-hosted chat last week. “It’s not final.”

A variety of environmental factors, including basic terrain issues on Guam that can make or break construction plans, are still at play. There is also a need to ensure no hazards are created in the process for the local population, either.

“So, when you think about transporting yourself to some other location, whether it’s in the United States or abroad, you have to worry about explosive arcs… you have to worry about the electromagnetic interference of the radars,” Hill added. “So, one of the first conflicts we had, it’s been in the press already, but I think it’s resolved, is if you’re going to build a hospital on this site, and you have a radar over here, is it okay to put radar energy through that site where you bring MEDEVAC [medical evacuation] helicopters in? The answer’s no.”

How exactly MDA and its Army and Navy partners will work around these issues remains to be seen. If the goal remains to at least have some components of the new Guam Defense System in place by 2026, decisions will have to start being made sooner rather than later.

As it stands now, MDA certainly seems committed to seeing new air and missile defenses on the island become a reality amid the growing threats in the region.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com