The United States has, for the first time since 2021, declassified its nuclear weapons stockpile inventory numbers. The move is a further indication of a new level of transparency around this highly sensitive information, which also reveals that last year, the United States dismantled only 69 retired nuclear warheads, the lowest number since 1994.

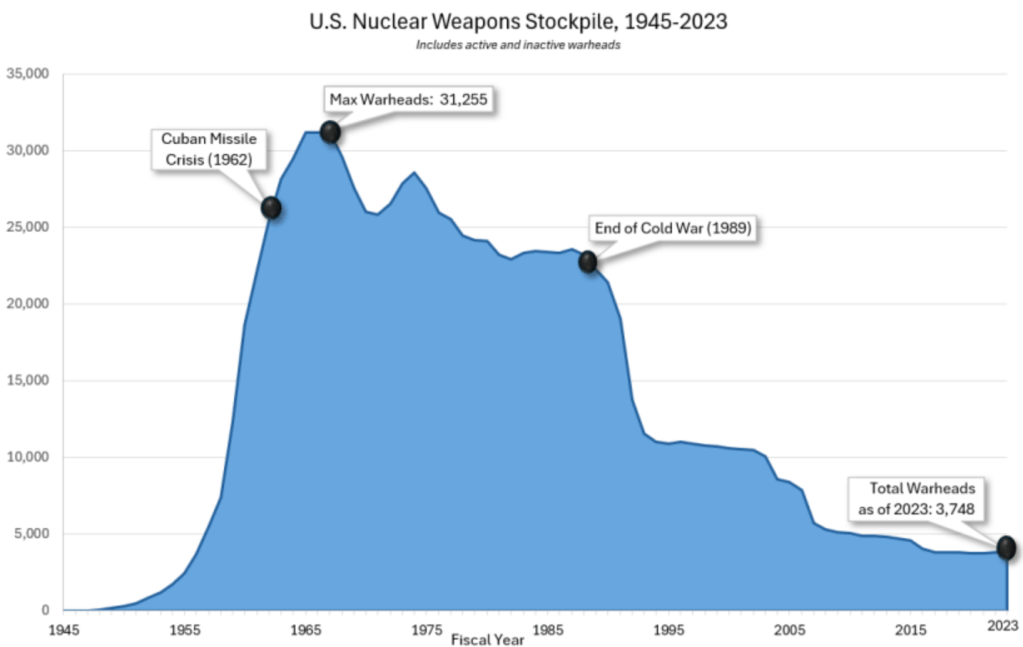

The latest information was published by the National Nuclear Security Administration or NNSA, which oversees America’s nuclear weapons stockpile. The standout figure is the overall total of nuclear warheads in the U.S. stockpile — 3,748 as of September 2023.

As defined by the NNSA, the stockpile includes both active and inactive strategic and non-strategic (tactical) warheads. While active warheads are those considered operational and ready for use, plus logistics spares, inactive ones are stored in depots in a non-operational status. While they could be deployed, this process would take some time, including installing their tritium bottles and other components that have a more limited lifespan.

Tritium, together with deuterium, is used to “boost” the chain reaction in nuclear weapons, making for a more powerful explosion. In thermonuclear weapons, tritium is typically used to boost the fission primary or first stage. Since tritium is radioactive and decays rapidly, these bottles are removed from inactive warheads.

Not included in the stockpile are retired warheads, which are considered non-functional, and dismantled warheads, which have already been broken down into their component parts.

Looking at the stockpile numbers in more detail, the NNSA compares the 3,748 warheads listed as of last September with the maximum level of 31,255 warheads achieved in 1967, at one of the most critical points of the Cold War. Meanwhile, when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the U.S. stockpile comprised 22,217 warheads. The latest figure represents an 88 percent reduction since 1967 and an 83 percent decrease since 1989.

Much of this reduction was achieved through the dismantling of non-strategic — i.e., tactical — nuclear weapons, numbers of which have been reduced by more than 90 percent since 1991.

Looking at strategic and non-strategic warheads combined, the NNSA reveals that 12,088 warheads were dismantled from fiscal years 1994 through 2023. Since September 2020 alone, 405 nuclear warheads have been dismantled. At the same time, there are around 2,000 more nuclear warheads that have been retired and now await dismantlement.

It’s important to note, however, that these figures only tell part of the story. Indeed, they have very likely been selected by the NNSA to highlight the overall reduction in the size of the stockpile, rather than the fact that the pace of this reduction has actually slowed in recent years.

Clearly, the U.S. nuclear stockpile is far smaller than during the Cold War and, while there have been more reductions since 2000, since 2007 the reduction has been relatively modest.

This is something that has been noted by the U.S.-based Federation of American Scientists (FAS) think tank, which has long campaigned for increased transparency around nuclear stockpiles around the world.

In his analysis of the NNSA’s revelations, Hans Kristensen, the director of the Nuclear Information Project at FAS, points out the following:

“Although the New Start treaty has had some indirect effect on the stockpile size due to reduced requirement, the biggest reductions since 2007 have been caused by changes in presidential guidance, strategy, and modernization programs.”

For example, in 2023 only 69 retired nuclear warheads were dismantled — the lowest number since 1994.

It’s because the rate of dismantlement has slowed that the aforementioned figure of retired warheads awaiting dismantlement — roughly 2,000 — is so high, at least compared to previous years. As FAS observes, in 2015 there were around 2,500 warheads stored and awaiting dismantlement.

While this suggests that dismantlement is now a lower priority, the reasons for that are unclear.

At the same time, Kristensen notes that the NNSA’s chart showing the fluctuations in the stockpile between 1945 and 2024 is not completely reliable:

“The chart released by NNSA is not entirely accurate because the period 2010-2023 does not show the 1,096-warhead drop between 2012 and 2018. As a result, the chart gives the impression that the stockpile is larger today than it actually is.”

Generally, though, the numbers provide a useful indication of how the size of the stockpile has remained relatively stable for the past seven years. Within that timeframe, changes in the total have not been driven by any policy shifts, but instead by the normal movements of warheads in and out of the stockpile due to maintenance work and life-extension efforts.

The decision to release this information is also interesting.

The degree of transparency around the U.S. nuclear stockpile has been determined primarily by the priorities of successive administrations, with the Obama administration being the first to introduce this policy of openness.

A period of nuclear secrecy was then ushered in under the Trump administration before being overturned by the Biden administration in its first year, after which warhead numbers were classified again. As a result, FAS requests for stockpile transparency were rejected in FY2021, FY2022, and FY2023. Figures for those years have now been declassified by the NNSA, however.

Presumably, the return to transparency has been calculated to encourage other nuclear-armed states to divulge similarly detailed information.

In its executive summary, the NNSA states:

“Increasing the transparency of states’ nuclear stockpiles is important to nonproliferation and disarmament efforts, including commitments under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and efforts to address all types of nuclear weapons, including deployed and non-deployed, and strategic and non-strategic.”

Whether Beijing and Moscow actually respond in kind is altogether more questionable, however, given their past track records in this regard.

It should be noted, too, that France and the United Kingdom — two nuclear-armed U.S. allies — have also consistently maintained a veil of secrecy over many details of their nuclear warfighting capacities.

Broader concerns about the future of nuclear arms control agreements have been growing in recent years. The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) between the United States and Russia, which despite its name covered nuclear and conventional missiles of various types, collapsed in 2019 and the Kremlin suspended its participation in the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) with Washington last year. In 2023, the Russian government also rescinded its ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, but has insisted it will not restart live nuclear weapon testing unless the United States does first. American officials have also now publicly accused their counterparts in Russia of working toward fielding a nuclear-armed space-based weapon, which would be in violation of the Outer Space Treaty.

With all this in mind, the value of transparency on the part of the United States, as long as it remains a one-way street, may become more questionable.

On the other hand, bearing in mind the current security environment, with tensions between Russia and the West at their worst for decades and with China rapidly building up its nuclear forces, some would argue that now is not the time to divulge more nuclear secrets, especially amid calls for the United States to expand its own nuclear arsenal.

Even without any kind of reciprocal disclosures from other nuclear powers, the return to U.S. transparency about its nuclear stockpile will still be welcomed by those who champion this kind of openness as a means of reassurance, that ultimately help mitigate the risk of reigniting nuclear arms races.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com