President Donald Trump has laid out a vision for a new Iron Dome air and missile defense system to shield the U.S. homeland, which directly hearkens back to the Reagan-era Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). A renewed call to deploy space-based anti-missile interceptors is a central aspect of the plan as it has been presented now, which focuses primarily on defending against ballistic and other higher-end missile threats. In addition, any explicit mention of the ever-growing danger posed by drones is conspicuously absent.

Trump had talked about the Iron Dome plan, which is also part of the current official Republican Party platform, on the campaign trail, and TWZ explored what was known about it in detail last year. The president has now provided new, more specific information in an executive order, a copy of which was posted online late last night.

It is important to note up front that the executive order confirms that the new U.S. Iron Dome system is unrelated to the Israeli Iron Dome system, despite the shared name and Trump’s off-handed references to the latter when talking about the former. The Iron Dome system from Israel’s Rafael, as seen in the video below, is designed primarily to defend against lower-end and localized threats like artillery rockets and mortar shells. It does now also have some capability against drones and cruise missiles.

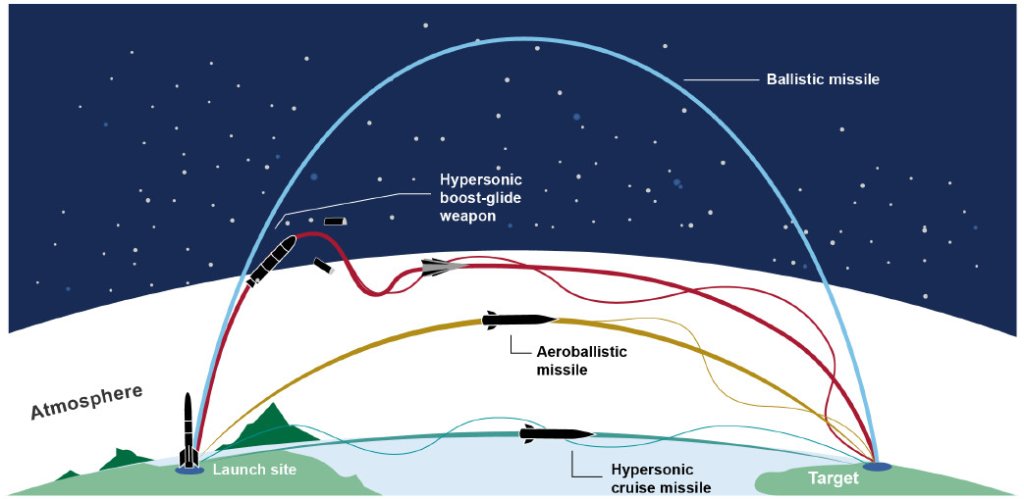

“The threat of attack by ballistic, hypersonic, and cruise missiles, and other advanced aerial attacks, remains the most catastrophic threat facing the United States,” the executive order declares. “Over the past 40 years, rather than lessening, the threat from next-generation strategic weapons has become more intense and complex with the development by peer and near-peer adversaries of next-generation delivery systems and their own homeland integrated air and missile defense capabilities.”

“He’s what we need, to immediately begin the construction of a state-of-the-art Iron Dome missile defense shield, which will be able to protect Americans,” Trump also said at an event yesterday.

The meat of the executive order is a call for a “next-generation missile defense shield” that “shall include, at a minimum, plans for” the following eight components:

- Defense of the United States against ballistic, hypersonic, advanced cruise missiles, and other next-generation aerial attacks from peer, near-peer, and rogue adversaries

- Acceleration of the deployment of the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor layer

- Development and deployment of proliferated space-based interceptors capable of boost-phase intercept

- Deployment of underlayer and terminal-phase intercept capabilities postured to defeat a countervalue attack

- Development and deployment of a custody layer of the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture

- Development and deployment of capabilities to defeat missile attacks prior to launch and in the boost phase

- Development and deployment of a secure supply chain for all components with next-generation security and resilience features

- Development and deployment of non-kinetic capabilities to augment the kinetic defeat of ballistic, hypersonic, advanced cruise missiles, and other next-generation aerial attacks

The executive order gives Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth just 60 days to present a path forward to implementing all of this and potentially more. The Office of Management and Budget is also tasked with formulating a cost estimate that will inform the upcoming proposed defense budget for the 2026 Fiscal Year.

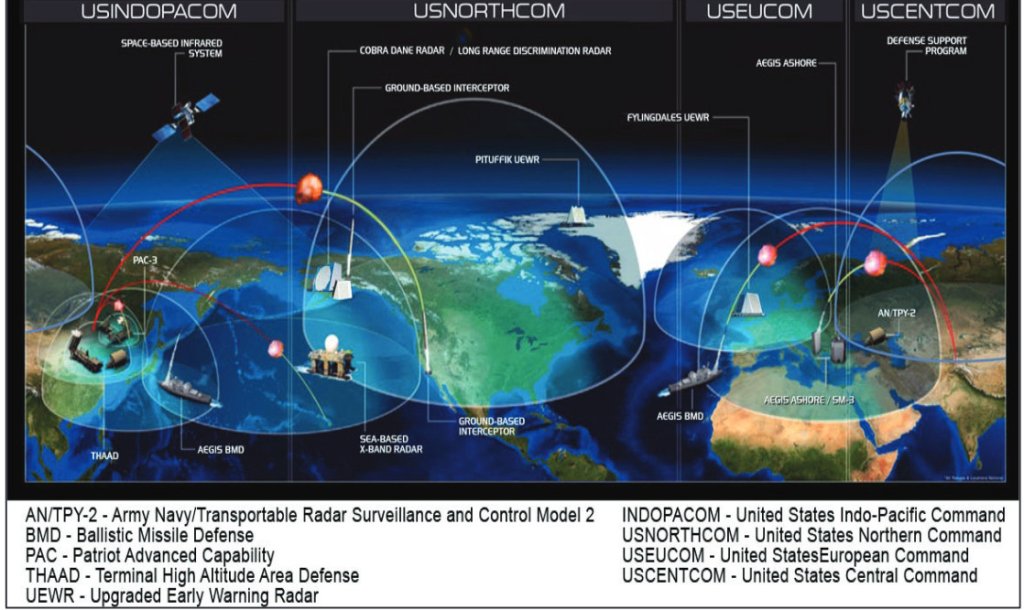

Additional provisions in the order require U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) and U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) to jointly produce “an updated assessment of the strategic missile threat to the Homeland” and “a prioritized set of locations to progressively defend against a countervalue attack by nuclear adversaries.” Calls for bolstering regional air and missile defense capabilities, and to work with allies and partners to that end, are also included.

The term countervalue is typically used in the context of planning for the employment of nuclear weapons, or responses to their use. It refers to the targeting of key military and other assets critical to a country’s ability to wage war. It is also worth pointing out here that larger ballistic missiles and their payloads, in general, typically reach hypersonic speeds in the latter stages of their flight. The hypersonic threats mentioned here refer to advanced designs with added emphasis on very high maneuverability and largely flat atmospheric trajectories that make them especially hard to track and defend against.

The U.S. military’s current dedicated homeland missile defense posture is focused primarily on shielding against limited strikes involving higher-end ballistic threats, and now increasingly novel hypersonic ones, primarily through a relatively small number of land-based interceptors tied to larger sensor and communications networks. Outside of the National Capital Region (NCR) around Washington, D.C., more general air defense duties, including protecting against incoming cruise missiles, falls almost exclusively to the U.S. Air Force (including the Air National Guard). Ground-based surface-to-air missiles (SAM) are deployed within the NCR, but the United States has not had a nation-wide SAM network since the 1970s.

Some of what the Iron Dome executive order now lays out, including the named Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS) and Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA), is already in the works. HBTSS’ central goal is the deployment of a new satellite constellation capable of not just providing improved early warning and situational awareness, but also fire control-quality tracks, including against highly maneuverable hypersonic threats. Two demonstrator HBTSS satellites are already in orbit. PWSA is working toward a multi-layered, distributed space-based networking backbone to support air and missile defense and other missions.

The U.S. military has also been working on new “underlayer and terminal-phase intercept capabilities,” including the Glide Phase Interceptor (GPI), for use against maneuvering hypersonic weapons. Efforts to develop options to neutralize ballistic and other missile threats at the point of launch, or even before they are launched (sometimes referred to as “left of launch”), from any domain, are not new, either.

The video below depicts a notional intercept involving various current and future missile defense capabilities, including GPI and HBTSS.

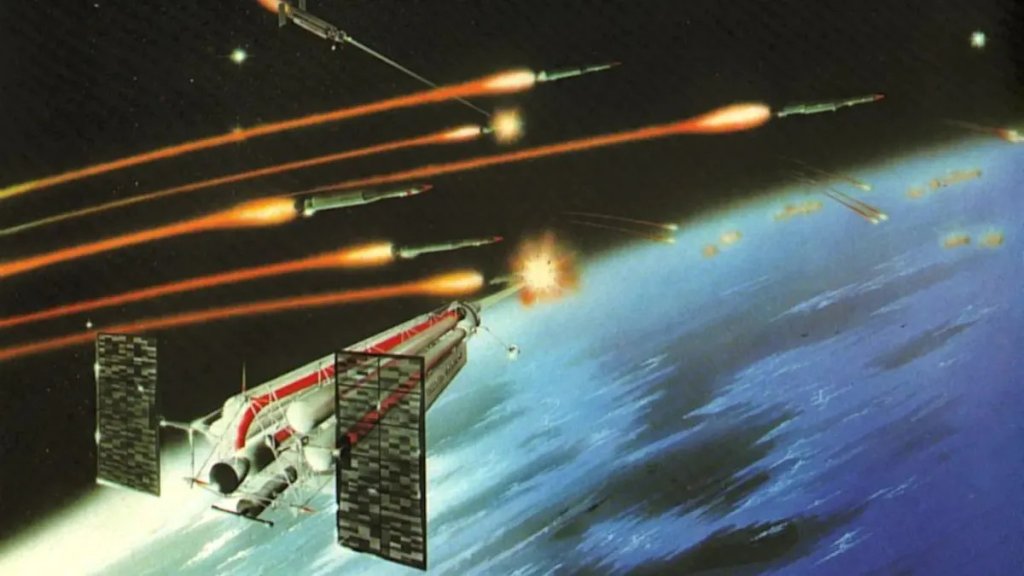

The new call for space-based interceptors is notable, especially amid concerns about the broader weaponization of space already. At the same time, orbital missile defense capabilities, including physical interceptors and directed energy weapons, were areas of particularly active interest in Trump’s first term. There were also calls to field new and improved counter-space capabilities, including space-based kinetic weapons, under President Joe Biden. One of former Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall’s last acts was to publish a report outlining a vision for future U.S. air and space capabilities by 2050 that explicitly mentions “counterspace systems [that] will include a cost-effective mix of weapons, both terrestrial and on orbit.”

As already noted, the Iron Dome executive order draws a direct comparison to Ronald Reagan’s SDI, which was also envisioned as an array of ground and space-based anti-missile capabilities paired with new sensors and communications networks. “President Ronald Reagan endeavored to build an effective defense against nuclear attacks, and while this program resulted in many technological advances, it was canceled before its goal could be realized,” the new order says.

However, highlighting SDI also raises immediate questions about the viability of the new Iron Dome plan. SDI was infamously nicknamed “Star Wars” by its critics and never came close to meeting its ambitious goals. President Bill Clinton finally brought it to a close for good in 1993 after some $30 billion – close to $56.1 billion in today’s dollars – had been spent. U.S. missile defense efforts subsequently coalesced around more limited objectives, which ultimately led to the creation of the Missile Defense Agency (MDA).

The same kinds of criticisms leveled against SDI, including fears of prompting new arms races, especially in space, and the significant technical and other challenges in implementing the desired capabilities, are likely to come up again with Trump’s Iron Dome plan. There will also be new cost concerns given that U.S. defense budgets are already facing increasing difficulties balancing competing priorities, especially around expensive nuclear modernization efforts.

In addition, since the U.S. government withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002, something the new executive order also explicitly mentions, Russia and China, especially, have already been investing in new capabilities specifically designed to defeat or at least challenge American missile defense capabilities. China is also significantly expanding its nuclear stockpile, a trend that could continue there and emerge elsewhere, in response to the Iron Dome plan. Missile defense advocates have argued, in turn, that these realities put the United States at a dangerous disadvantage that requires additional protective measures.

There is also a question of prioritization, which brings us to the matter of uncrewed aerial threats. At best, the Iron Dome plan lumps drones into the category of threats capable of executing “other next-generation aerial attacks,” but that would de-emphasize the serious dangers posed now by even lower-end weaponized commercial designs. Alarms bells about the adequacy of domestic U.S. air defense capabilities, or lack thereof, against less advanced threats like drones and cruise missiles have increasingly been ringing in recent years. The line between drones, especially longer-range kamikaze types, and traditional cruise missiles is becoming increasingly blurry, too.

TWZ has for years now been highlighting drone threats, which are already on the cusp of becoming newly significant thanks to artificial intelligence and machine learning-driven technological developments that are also increasingly proliferating. As we wrote when talking about Trump’s Iron Dome ambitions as they were known last summer:

“Drones, even lower-end weaponized commercial types, present an ever-growing threat in their own right, something that the war in Ukraine has helped finally push into the mainstream consciousness. The barrier to entry in this domain is extremely low, with terrorists, criminal groups, and other non-state actors – like the [Iranian-backed] Houthis [in Yemen] – increasingly using uncrewed aerial systems to launch attacks, as well as to conduct surveillance. Even relatively cheap examples of these systems can fly over extreme distances and strike with pinpoint accuracy. Their low and slow characteristics, and the fact that launch points can come from so far away, make them very hard to defend against. This poses a whole new threat dimension to the U.S., one in which the homeland is clearly vulnerable.”

“Looking outward for drone threats from America’s borders only factors in one facet of the issue. Attacks present the additional danger of being something that small groups or even individuals within the United States, can readily mount. The complexity of these potential attacks will only increase as the hardware and software to execute them proliferates even in the commercial space.”

“Reports of concerning drone activity over military bases and training ranges, as well as other sensitive sites, inside the United States, are only becoming more commonplace. U.S. authorities have said that many sightings of what are now commonly called unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP), previously referred to as unidentified flying objects (UFO), have been assessed to have been uncrewed aircraft, as well as balloons, on closer examination, as well. It’s worth noting here that the U.S. military and other armed forces around the world, especially China, have been actively working to develop and field high-altitude balloons as penetrating launch platforms for drones and munitions, among other missions.”

Still-unexplained drone incursions over Langley Air Force Base in Virginia in December 2023, which TWZ was first to report, helped turn the issue into a national cause celebre last year. A flurry of reported drone sightings in the skies over New Jersey late last year, which we were also first to report on and evolved into something of nationwide hysteria, both underscored and obscured the very real national security concerns at play. Drone incursions around bases hosting U.S. forces in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe have made clear this is a global issue.

The Pentagon did notably roll out a new counter-drone strategy in 2024. At the same time, U.S. military officials highlighted significant policy and other challenges still limiting their ability to respond to uncrewed aerial threats domestically last year.

It is possible that the new Trump administration may seek to address the drone threat through other actions. Trump has already pushed for officials to loosen restrictions on using force against uncrewed aerial systems along the southern border through a separate executive order.

Though we now have more specific details, there is much still to learn about Trump’s new Iron Dome plan, and how and when it might implemented, in general.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com