The U.S. Air Force’s vaunted Self-protect High Energy Laser Demonstrator (SHiELD) program closed out without ever reaching its goal of testing a laser-directed energy weapon on a fighter. This revelation came just days after the U.S. Army disclosed it was facing major hurdles with its new laser-armed variants of the 8×8 Stryker light armored vehicles. Earlier this year, the Air Force also announced it was no longer proceeding with a long-held plan to fit a laser weapon onto an AC-130J Ghostrider gunship. These are just the latest examples of U.S. military laser weapon programs facing stark reality checks despite significant advances in this technology in recent years.

Military.com was first to report on the end of the SHiELD program last Friday. SHiELD was a three-part initiative that involved separate development of the laser, turreted mount, and pod under the Laser Advancements for Next-generation Compact Environments (LANCE), SHiELD Turret Research in Aero Effects (STRAFE), and Laser Pod Research & Development (LPRD) subprograms, respectively.

“The SHiELD program has concluded, and there are no plans for further testing and evaluation,” Dr. Ted Ortiz, the head of the program at the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), told Military.com. “The Air Force has not installed a laser pod on a fighter jet test bed.”

Boeing, which was the lead contractor on the LPRD component, did flight test a pre-prototype pod ‘shape‘ without any systems loaded onto an Air Force F-15 in 2019.

“Through SHiELD and related efforts, AFRL has made significant advances in the readiness of airborne HEL [high-energy laser] technology, and we continue to mature airborne HEL weapons technology for the operational needs of today and tomorrow,” Ortiz added.

To date, the exact power of the LANCE laser, which Lockheed Martin designed and built, does not appear to have been disclosed. Past reporting has suggested that it was less than 100 kilowatts.

The Air Force also successfully demonstrated the ability of a separate “representative” laser with an unspecified rating, called the Demonstrator Laser Weapon System (DLWS), installed on the ground to shoot down air-launched missiles in 2019 as part of the SHiELD effort.

Details about progress on the STRAFE component, where Northrop Grumman was the prime contractor, are limited.

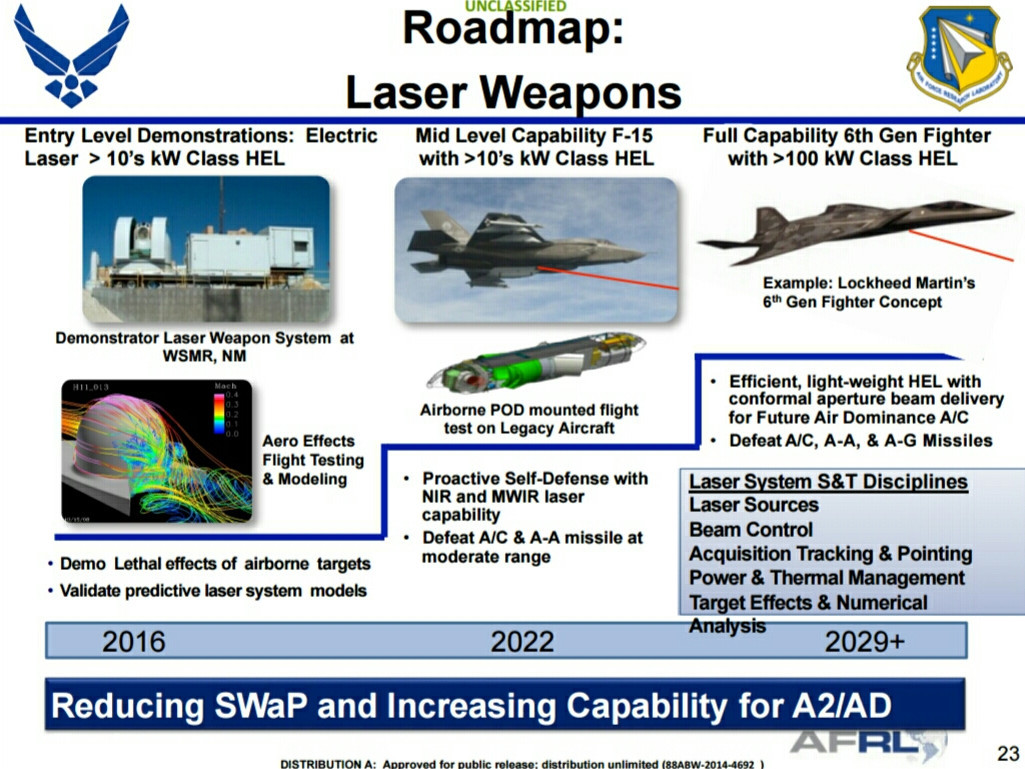

SHiELD traces its roots back at least to the early 2010s and was publicly focused on the development of a practical podded laser-directed energy weapon that crewed combat jets like the F-15 or F-16 could carry. Ostensibly, the primary purpose of the system would have been to help protect those aircraft from incoming air-to-air and surface-to-air missiles. Documents The War Zone obtained in 2022 via the Freedom of Information Act revealed a link between SHiELD’s origins and interest in a more multi-purpose laser weapon to arm a notional sixth-generation stealthy crewed combat jet envisioned in study that preceded the Air Force’s current Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) effort. You can read more about all of this here.

As of 2017, the Air Force had hoped to load a complete SHiELD system onto a fighter for an initial flight sometime in 2021. By 2020, that timeline had slipped to 2025.

SHiELD is not the first high-profile laser weapon program the Air Force has revealed that it has spun down just this year. In March, the Air Force confirmed to The War Zone it had axed long-standing, but also much-delayed plans to test a high-energy laser weapon on an AC-130J Ghostrider gunship under its Airborne High Energy Laser (AHEL) program, citing unspecified “technical challenges.” The service added that, “as a result, the program was re-focused on ground testing to improve operations and reliability to posture for a successful hand off for use by other agencies.”

It remains unknown who those “other agencies” might be.

Separately, Doug Bush also gave a less than glowing report on the results so far of Army field testing of laser-armed Strykers, also known as Directed Energy Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense (DE M-SHORAD) vehicles, at a hearing before members of the Senate Appropriations last Wednesday. Bush is the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology.

The laser used in the DE M-SHORAD system has a 50-kilowatt power rating and is designed primarily to destroy smaller drones, as well as incoming artillery rockets, shells, and mortar projectiles. The Army is known to have received four prototype DE M-SHORADs and to have sent them all to undisclosed locations in the Middle East as of March, according to Breaking Defense.

“What we’re finding is where the challenges are with directed energy at different power levels,” Bush told lawmakers at the hearing last week, per Breaking Defense. “That [50-kilowatt] power level is proving challenging to incorporate into a vehicle that has to move around constantly – the heat dissipation, the amount of electronics, kind of the wear and tear of a vehicle in a tactical environment versus a fixed site.”

Bush did say that other unspecified laser weapons emplaced at fixed sites “are proving successful” for “some” unspecified users. This might be a reference to 20-kilowatt Palletized High Energy Lasers (P-HEL), which are versions of the BlueHalo LOCUST laser weapon system, at least two of which the Army has sent to foreign locales since 2022, according to Military.com.

Growing pains for advanced weapon systems, especially when they start being tested in real-world environments, are hardly uncommon. Laser directed energy weapons do look to have been having a particularly rough time in recent years despite technological and material advancements having fully brought them out of the realm of science and making them more practical than ever. You can read more about how this has been achieved particularly through progress in the development of new and improved solid-state lasers in this past War Zone feature.

In addition, there has been a steady walking back of pronouncements made during the 2010s that laser directed energy weapons were on the cusp of becoming operational game-changers.

Continued technical challenges are certainly part of the equation.

“If you’re just making stuff bigger and bigger, you also need more electrical power and you need more thermal management systems,” Dr. Rob Afzal, Lockheed Martin Senior Fellow, Laser and Sensor Systems, told the War Zone in an interview in 2020. “Now, let’s say you’ve achieved this power. If you want to reach a longer range, it means that your beam is going to propagate through the atmosphere for a longer distance, and you have to be able to maintain the aim point, right?”

“Then, the atmosphere will begin to distort the laser beam, depending on the type of atmosphere you’re in,” he continued. “There’s technology that’s been developed, but is still maturing where you need to be able to measure the distortion in the atmosphere and then compensate for it, so that the beam propagates through the atmosphere and focuses tightly on to a target.”

“For the tactical airborne, the hardest piece of the technology is the ‘SWAP’—the size, weight, and power. The issue with tactical fighters is, there is no room for anything on a tactical fighter. All platforms are filled to the brim, right? As soon as you have a platform, you start putting stuff on it,” Afzal added, speaking specifically about SHiELD. “A tactical fighter is clearly, that’s been the biggest challenge from being able to make something small enough and powerful enough to be useful. So, SHiELD is the beginning of this activity and as technology continues to miniaturize, and if you could trend where this technology is going, the laser systems are getting smaller and more powerful.”

Separately in 2020, then-Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Mike Griffin raised somewhat similar issues while pouring cold water on Missile Defense Agency (MDA) aims to demonstrate the feasibility of using a drone armed with a laser weapon to shoot down enemy ballistic missiles during the initial boost phases of their flights.

“As a weapon system to equip an airplane with the lasers we think necessary in terms of their power level …and get them to altitudes where atmospheric turbulence can be mitigated appropriately, that combination of things can’t go on one platform,” Griffin said while speaking at the Washington Space Business Roundtable. “I’m extremely skeptical that we can put a large laser on an aircraft and use it to shoot down an adversary missile even from very close.”

There were other non-laser-related questions about how such a capability would be employed and MDA ultimately chose not to pursue it. This all followed the cancelation in 2011 of an MDA program to meet the same operational requirement using a modified Boeing 747, known as the YAL-1 Airborne Laser, armed with a large and complex chemical laser weapon.

In 2019, Griffin had also announced the shelving of an even more ambitious directed energy missile defense project involving a space-based particle beam weapon.

It is worth noting here that there have been numerous successful aerial demonstrations of solid-state laser weapon systems in recent years in the United States and elsewhere around the world. This includes a Raytheon design small enough to fit inside a pod that could be carried on the stub wing of an AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, which was tested in 2017. However, to date, none of these systems look to have entered any kind of real operational service, at least that we know of, pointing to continued challenges with the technology.

Speaking to Breaking Defense in January about the DE M-SHORAD systems and their impending field test, Vice Chief of Staff of the Army Gen. James Mingus echoed much of what Dr. Afzal had previously explained to The War Zone.

“Our high-energy lasers are so susceptible to weather,” he explained. “That’s why I think this is going to be a great laboratory because anytime there’s a dust storm, anytime there’s that kind of thing, it starts to alter the physics of the light particles that actually shoot that beam.”

“You may have a 50-kilowatt laser, [but] at 10 kilometers can you put at least four kilowatts in a centimeter square because … that’s what you need to burn through a quarter inch steel plate?” Mingus continued. “But that’s really hard to get … from a big beam to get the small portion of it on the exact spot to be able to burn at that high intensity and any kind of dust particle or that starts to disrupt that.”

Back in 2020, Afzal did also note that finding adequate ‘SWAP’ space to support laser weapon systems can still be an issue even with larger platforms like ships. “There’s less room on a ship than you would think.”

The Navy has been one of the more active U.S. military branches when it comes to developing and actually fielding various laser directed energy weapons. This includes ones just intended to blind sensors and seekers and those capable of actually physically damaging or destroying targets. This has helped in no small part by the fact that ships do still generally have more ‘SWAP’ to work with than something like a fighter or a ground vehicle. Still, even that service’s laser ambitions have also been tempered by technical challenges and limitations.

Technical issues clearly aren’t the only hurdles. Assistant Secretary of the Army Bush’s comments last week also speak to the new kinds of demands units in the field, and not just those in the Army, will face just in operating and maintaining laser directed energy weapons under field conditions. Doing so in more challenging environments, like in locales with extremely hot and cold temperatures, will only compound those issues.

“Lasers are complicated. This is not a Humvee that’s sitting in the motor pool,” now-retired Army Lt. Gen. Daniel Karbler, then the head of U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command, said on the sidelines of the Space and Missile Defense (SMD) Symposium last year per Breaking Defense. “Many of the some of the main [laser] components… you’re not going to have a supply room or maintenance office full of repair parts. Those are going to be ones that are going to have to be built out.”

“We’ve had three or four systems in the AFRICOM AOR [US Africa Command area of responsibility] and essentially it takes three to make one,” Army Maj. Gen. Sean Gainey, head of the Pentagon’s Joint Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems Office, said at the same event. It is “a consistent challenge.”

This and the other aforementioned challenges are also ones that the U.S. armed forces do look to remain interested in trying to surmount, at least on certain levels. Despite the very real hurdles a slew of laser directed energy weapon programs have faced in recent years, new programs are still being initiated. Just last month, the U.S. Marine Corps announced that it would also be testing a version of BlueHalo’s LOCUST mounted on a 4×4 Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV), as depicted below.

Broadly speaking, laser directed energy weapons do still hold the promise of largely unconstrained magazine depth – as long as there is sufficient power and cooling – and fast-as-light precision engagements against various tiers of threats, including top-priority ones like drones and cruise missiles. Though they can only focus their energy on a single target at once, they can rapidly redirect their attention from one to another.

So, how and when the hurdles still facing laser weapons might be surmounted remains to be seen. Only time will tell whether other directed energy weapon types, like high-power microwave systems, prove more practical, at least in near-term timelines and against pressing threats like drone swarms.

Whatever the case, there are clearly real issues still standing between the U.S. military and a laser directed energy weapon future, despite continued commitments across the services.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com