The United States’ decision to dramatically increase its long-range fire capabilities in Europe starting in 2026 appears set to trigger a response from Russia, as a new missile race gathers pace in Europe. Announced yesterday, the U.S. plan calls for “episodic deployments” followed by “longer-term stationing” of various types of long-range missiles suggesting that, eventually, at least some of these weapons will be permanently deployed in Germany, in a throwback to the Cold War era.

The United States will deploy to Germany a range of advanced ground-launched weapons, including the SM-6 multi-purpose missile and Tomahawk cruise missile as well as “developmental hypersonic weapons” — a reference to the yet-to-be-fielded Dark Eagle and potentially others, like the Operational Fires (OpFires) ground-launched hypersonic missile system and the Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) short-range ballistic missile, both of which are also now in development.

In a joint statement, the United States and Germany said the deployment of the new weapons would “demonstrate the United States’ commitment to NATO and its contributions to European integrated deterrence.”

In terms of timelines for putting these missiles in Germany, the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy are already fielding the SM-6 and Tomahawk missiles as part of ground-based systems and these have been deployed on a temporary basis in both Europe and the Pacific.

Less clear is whether the U.S. Army’s Dark Eagle will be ready for deployment to Europe in 2026. Having had a troubled development phase so far, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) told Congress last month that the first complete battery is now expected to be fielded in fiscal year 2025.

The U.S. Army’s Dark Eagle ground-based hypersonic weapon. (U.S. Army)

Most critically, yesterday’s U.S.-German statement notes that the weapons deployed will have “significantly longer range than current land-based fires in Europe.”

As we have reported in the past, the U.S. Army’s Dark Eagle, also known as the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, or LRHW, is planned to be able to strike targets at least 1,725 miles away. The Dark Eagle comprises a large rocket booster with an unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle on top. Once the boost-glide vehicle has been propelled to the desired speed and altitude, it separates and hurtles down toward its target along an atmospheric flight trajectory, at a speed of up to Mach 17.

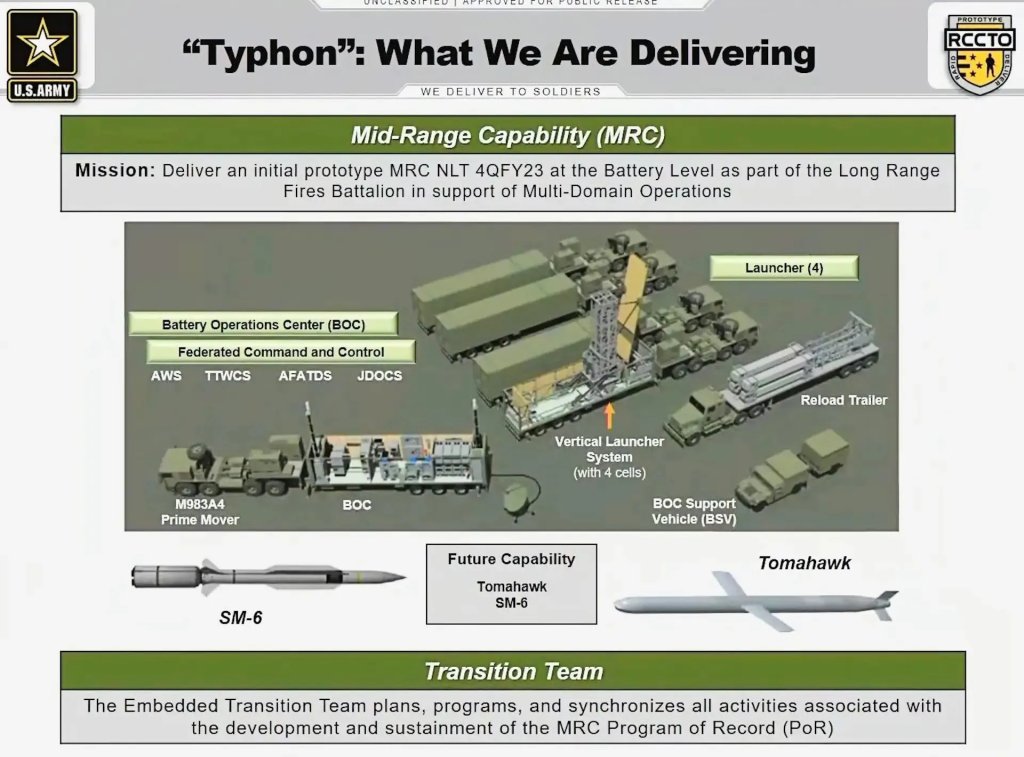

Meanwhile, the U.S. Army uses the Typhon system to fire SM-6 and Tomahawk missiles. A very similar setup is also employed by the U.S. Navy, which uses the Mk 70 Mod 1 Expeditionary Launcher to fire SM-6 missiles. One key operational difference is the fact that the Army only plans to use the ground-launched SM-6 to strike targets on the ground or at sea, while the Navy has not ruled out using it to engage aerial threats.

For its part, the U.S. Marine Corps is also fielding a ground-based Tomahawk capability, but using a completely different launch system based around a remotely-operated derivative of the 4×4 Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV).

Turning now to these missiles, the SM-6 was originally designed as a sea-launched surface-to-air weapon and now has also found an air-launched application. When ground-launched, the SM-6 can be used as a quasi-ballistic missile for land attack, although its range has not been confirmed. Estimates suggest the SM-6 has a range of up to 290 miles in this mode, although an extended-range version is also in the works, expected to offer significantly greater reach (and greater speed). The Army has previously described its ground-launched SM-6 as a “strategic” weapon system to prosecute higher-value targets like air defense assets and command and control nodes, but it’s essentially a short-range ballistic missile (SRBM). It can also strike targets at sea.

As for the Tomahawk, an earlier ground-launched version of the subsonic cruise missile, the U.S. Air Force BGM-109G Gryphon, was scrapped under the INF. Now back in use in non-nuclear form, the ground-launched version of the iconic Tomahawk cruise missile is able to hold targets on land and at sea at risk at a range of roughly 1,000 miles from where it is deployed.

For comparison, the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) short-range ballistic missile, the longest-range ground-based missile system currently in U.S. Army service, can only reach targets out to approximately 186 miles.

It should be recalled that, under the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF, signed by the Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President Ronald Reagan in 1987, Russia and the United States were prohibited from deploying nuclear or conventionally armed ground-based cruise and ballistic missiles with ranges between 310 and 3,420 miles.

While an entire category of weapons was removed in the final years of the Cold War as the result of the INF, U.S. President Donald Trump formally withdrew from the treaty in 2019, ostensibly over Russia’s fielding of a prohibited ground-based cruise missile system, the 9M729 (SSC-8 Screwdriver), something the Kremlin continues to deny it has done.

Russia claimed it had imposed a moratorium on its own development of missiles previously outlawed by the INF treaty, but in response to U.S. developments in this field — as well as increasing tensions with NATO against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine — has more recently changed its stance.

When asked today about the new U.S. plans, Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov described the move as “yet another and very visible confirmation of the extremely destabilizing U.S. policy in the ‘post-INF’ era.”

Ryabkov continued: “As we have repeatedly warned, the actions of the United States and its satellites to create additional missile threats to Russia will not go without a proper response on our part.”

The deputy foreign minister then restated that Russian President Vladimir Putin was considering the fate of the self-imposed moratorium on the deployment of INF-busting missiles.

“The necessary work on the preparation of compensatory countermeasures by Russian specialized agencies was started in advance and is being carried out on a systematic basis,” Ryabkov said, with no mention of any specific weapons systems that this might encompass.

Late last month, Putin issued what appeared to be a call for the production relaunch of intermediate and shorter-range nuclear-capable missiles.

Pointing to the U.S. temporary deployment of intermediate and shorter-range missiles — albeit the conventionally armed SM-6 and Tomahawk, rather than anything nuclear — in Denmark and the Philippines, Putin told Russia’s Security Council: “We need to respond to this and make decisions about what we will have to do in this direction next.”

“Apparently, we need to start manufacturing these strike systems and then, based on the actual situation, make decisions about where — if necessary to ensure our safety — to place them,” Putin added.

Days before that, Putin had issued a stark warning to Berlin, specifically, outlining potential retaliatory options if German-supplied weapons were used by Ukraine against targets in Russia. Were that to happen, Russia could supply long-range weapons to unspecified “regions” around the world where they could be used for strikes against Western targets, Putin said.

For some time now, Russia has discussed the production and deployment of equivalent INF-busting missiles as a response to U.S. deployments of similar. However, as Dmitry Stefanovich, a Research Fellow at the Center for International Security, IMEMO RAS, told TWZ, there have so far been no public Russian tests of these kinds of weapons.

Putin has also recently threatened to deploy conventional missiles within striking distance of the United States and its European allies, in response to these countries having given Ukraine permission to use certain long-range weapons they supplied to strike targets deeper within Russia. This is in addition to a string of nuclear threats and related drills that have been made in an effort to dissuade Western involvement in the war in Ukraine.

It seems all but certain, therefore, that yesterday’s U.S.-German announcement will draw some kind of response from Moscow.

“The most significant implication is that it indicates that NATO and Russia are back in a tit-for-tat INF missile race in Europe,” Hans Kristensen, the director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) think tank, told TWZ. “It is almost inevitable that Russia will counter-react with announcements about its own INF missiles, including potentially ballistic missiles.”

Kristensen points out that while there are already air- and sea-based cruise missiles in the region that provide INF range, the addition of quick-strike quasi-ballistic missile missiles (the SM-6) and hypersonic missiles (Dark Eagle) will likely “increase crisis instability and the risk of overreaction.”

“The two sides went down this path half a century ago and it didn’t go well,” Kristensen adds. “One would hope they had learned the lesson, but apparently not.”

Reflecting the potential for escalation, one category of weapon that has been raised by some analysts as a potential Russian counter to the U.S. deployments is the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM).

According to this logic, the U.S. long-range fire capabilities that will be deployed in Europe are essentially strategic weapons, since they are able to hold high-value targets deep within Russia at risk, including critical leadership and military command centers, among others.

As such, Russia could respond by increasing its armory of strategic weapons that are able to reach similar targets in the continental United States. Here, the preferred weapon would likely be ICBMs with (potentially multiple) nuclear warheads.

There have also been suggestions that Russia might reprioritize work on the RS-26 Rubezh, described by Moscow as an ICBM, with the ability to carry multiple warheads or, reportedly, an Avangard hypersonic boost-glide vehicle. The recent status of the RS-26 is rather unclear, with reports in 2018 that the program had been suspended in favor of other strategic weapons, including hypersonic ones, although this may now change.

Derived from the RS-24 Yars ICBM, the RS-26 has been seen by Western observers as a modern equivalent to the RSD-10 Pioneer (SS-20 Saber), an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) that played a major role in late Cold War defense planning and was then outlawed under the INF treaty.

The RS-26 began tests in around 2011, with most of these taking it over generally shorter ranges, including multiple test flights of around 1,200 miles, suggesting to the West that it might indeed be intended as an IRBM rather than an ICBM.

Such a weapon would reintroduce another dynamic to the European theater, with a nuclear-capable Russian ballistic missile the range of which is optimized for striking Western European capitals as well as key military targets. In this way, the RS-26 could very much become an analog to the RSD-10 Pioneer and could be equally impactful on the continent’s strategic security situation.

Writing back in 2014, before the U.S. withdrawal from the INF treaty, Jeffrey Lewis, director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, raised potential concerns about the RS-26:

“While Russia might hint that the RS-26 is intended for China, the reality is that it also seems to be designed to threaten NATO forces in Western Europe to deter them from coming to the aid of the alliance’s newer members closer to Russia’s tender embraces.”

Now, of course, Russia is looking for new ways to deter NATO from aiding Ukraine, including issuing nuclear threats, and Moscow may yet turn to the RS-26 to back up this rhetoric as well as respond to the U.S. deployment of conventionally armed long-range missiles in Germany. There remains a question, however, about Russia’s ability to fund such a program, amid the demands of other big-ticket acquisitions and the war in Ukraine.

There are other options, too, which may well be more likely — and achievable.

According to Dmitry Stefanovich, the announcement might prompt Russia to demonstrate some of its previously announced INF-busting weapons. As well as the 9M729 cruise missile, he identifies something called the “land-based intermediate-range hypersonic missile system,” which could be a ground-launched derivative of the Zircon naval hypersonic missile, or possibly an upgraded Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile. With reports of the use of the Zircon in Ukraine, it would appear that this particular hypersonic weapon is already being forward-deployed in the European theater.

Stefanovich continued: “It remains to be seen what might be the production and deployment tempo [of INF-busting weapons], as well as the areas for such a deployment, with both the NATO-focused Leningrad Military District or the traditional training unit for new weapons at Kapustin Yar in the Southern Military District being possible.”

The heavily militarized Kaliningrad exclave could also be a tempting base for additional missiles, already hosting short-range ballistic missiles as well as deployments by MiG-31 Foxhound aircraft armed with Kinzhal hypersonic missiles. Due to its proximity to NATO countries, Kaliningrad puts even shorter-range weapons within reach of a wide range of targets they would not be able to reach from Russia’s primary border.

Once again, however, the response from Moscow may be more obviously directed at Washington, which could see an uptick in the previously announced and partially demonstrated patrols of warships and submarines armed with hypersonic missiles and subsonic cruise missiles near U.S. coasts. Another U.S.-focused option could see the deployment of ICBMs — potentially even of new types — in the Russian Far East.

The burgeoning arms race in Europe now looks like it will also include France, Germany, Italy, and Poland. A coalition of those four European NATO members today signed a Letter of Intent on a European Long-Range Strike Approach, or ELSA, which aims to “develop, produce, and deliver capabilities in the area of long-range strike, which are critically needed to deter and defend on our continent.”

While ELSA is a longer-term initiative, the details of which are still to be resolved, it points again to a growing focus on long-range fire capabilities in Europe and may well ultimately have a significant effect on the strategic balance on the continent.

Perhaps inevitably, the continuing collapse of the INF treaty is now being played out as a new kind of missile race in Europe. While the United States has now outlined its commitment to increasing its long-range fire capabilities there, and European countries are also starting to pursue the same goals, the continent waits to see exactly what kind of response will come from Russia.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com