During World War II, the British laid down underwater pipelines stretching across the English Channel to France. Operation PLUTO – an acronym for “Pipe Lines Under the Ocean” or, as it’s also been described, “Pipeline Underwater Transportation of Oil” – was designed to supply fuel from England and the Isle of Wight in support of the Allied invasion of Normandy.

Beginning with the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, the invasion required vast quantities of fuel. As David Edgerton notes in his book Britain’s War Machine: Weapons, Resources, and Experts in the Second World War, Operation PLUTO was designed to supply around 4,000–5,000 tons of fuel a day – some 40-50 per cent of the Allied fuel requirement at D+12 (meaning 12 days after D-Day). But how successful was Operation PLUTO in helping to supply the necessary fuel for the Allies?

Oil and Britain’s war

Securing oil, as well as having access to it, became a crucial aspect of how warfare was conducted in the twentieth century. Petroleum, a fossil fuel also known as crude oil, was required to both fuel and lubricate the modern weapons platforms which emerged during World War I, including submarines, aircraft, trucks, and tanks. By 1918, as Anand Toprani notes in his book Oil and the Great Powers: Britain and Germany, 1914 to 1945, oil was essential to the functioning of the modern war economy – affecting sectors such as heavy industry, transportation, and agriculture. During World War II, the demand for oil only increased.

Prior to 1939, vast quantities of protected petroleum were stored across Britain in anticipation of the fuel demands of the Royal Air Force (RAF). As Tim Whittle explains in an academic paper on wartime fuel supply and Operation PLUTO, storage depots were constructed in rural areas from Newcastle in the north of England down to Southampton on the country’s southern coast. Plans to build smaller Air Force Distribution Depots (AFDD) were laid in July 1939, while the construction of main Air Force Reserve Depots (AFRD), which could typically hold around 4,400 tons (4,000 tonnes) of fuel, began in 1938.

When war broke out on September 3, 1939, a Petroleum Board was formed. This was a non-government organization consisting of all the major oil companies designed to coordinate petroleum supplies across the country. The government also had its own Secretary for Petroleum, a position filled by the Conservative member of parliament, Geoffrey Lloyd between 1940-1942. The construction of protected petroleum stores rapidly increased between 1940-1942, with most large installations camouflaged for safety.

The supply and movement of petroleum in Britain

Britain did not enjoy a plentiful domestic supply of crude oil during the period. As such, it needed to be obtained from elsewhere to meet the wartime demand. Britain drew on the resources of its empire here, notably the Middle East. An even greater supply of petroleum came from the U.S., particularly as a result of the Lend-Lease Act of March 1941. As Edgerton notes, by the middle of the war nearly all of Britain’s petroleum products were supplied by the U.S.

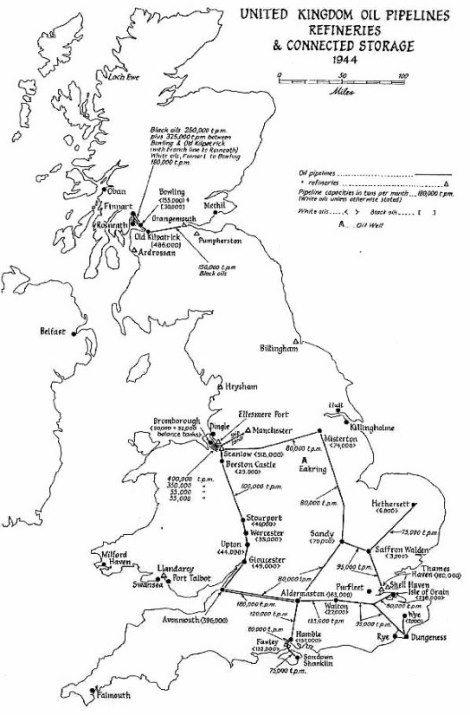

The aerial bombardment of Britain by Germany between 1940-1941 placed a major strain on how petroleum was moved around the country once it arrived. With the repeated targeting of petroleum storage installations, particularly to the south and southeast of England, and the closure of England’s eastern and southern coastal ports, a vast pipeline network was constructed to supply fuel to the various RAF stations from the west of the country. This pipeline network, known as the Government Pipeline Storage System (GPSS) pipeline, formed the backbone of the PLUTO pipelines.

The starting point of the GPSS network was Avonmouth, a port and outer suburb of Bristol on England’s west coast.

Work on the Avonmouth/Thames pipeline, the first GPSS pipeline which connected the docks of Avonmouth with a new depot on the river Thames, started in June 1941. It was completed later that year, and measured just shy of 100 miles in length. Avonmouth was subsequently connected to the river Mersey, Liverpool, forming a South/North pipeline, and, from there, connections were made across mainland England bar the southwest.

Operation PLUTO

When Britain and the Allies began looking for fuel supply options ahead of an invasion of Nazi-occupied France, PLUTO was designed as an underwater extension of the GPSS pipeline. The PLUTO pipelines were not, it should be said, the main means by which petroleum was to be supplied to the continent in this scenario. Rather, PLUTO was meant to provide petroleum before a more abundant supply could be delivered via tankers.

Plans for PLUTO were laid in 1942. In April, Louis Mountbatten, then chief of the Combined Operations Command, asked the government minister in charge of the Petroleum Warfare Department, Geoffrey-Lloyd, whether a pipeline could be laid under the English Channel in preparation for an invasion of German-occupied France.

Working alongside Combined Operations Command, Royal Navy Captain John Hutchings was appointed the Senior Naval Officer in command of Operation PLUTO in July 1943, having already assisted Combined Operations Command since the end of 1942.

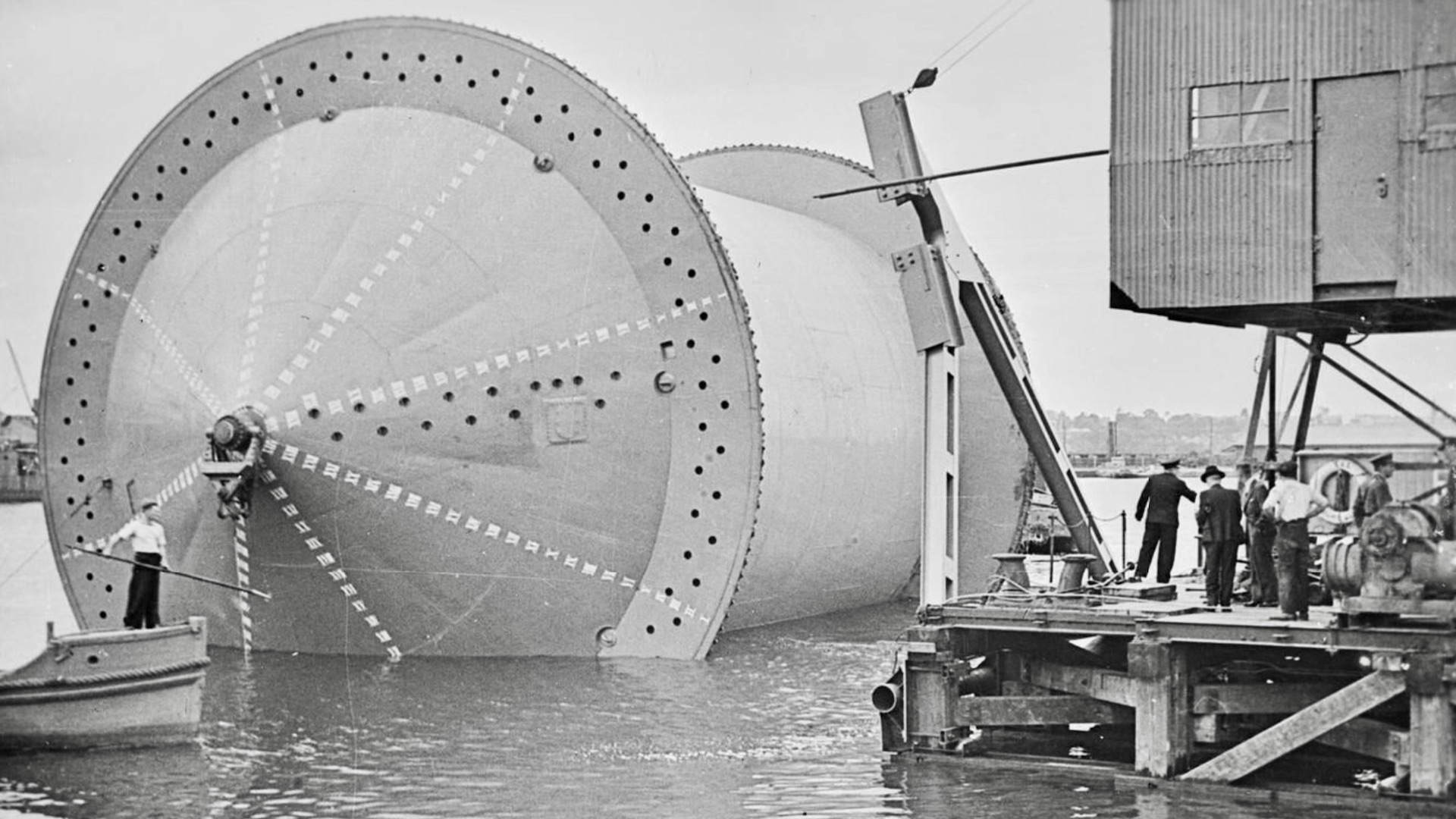

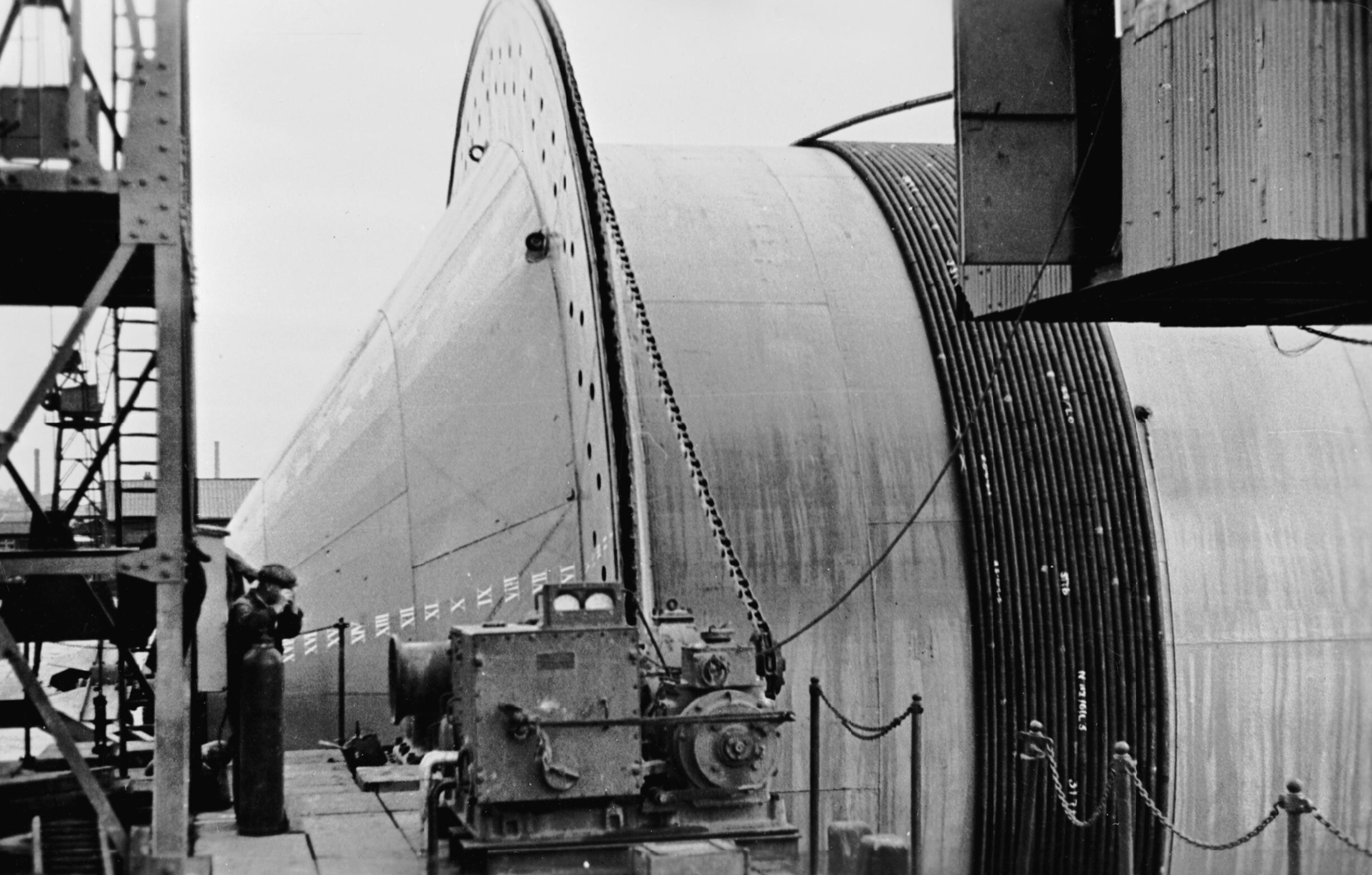

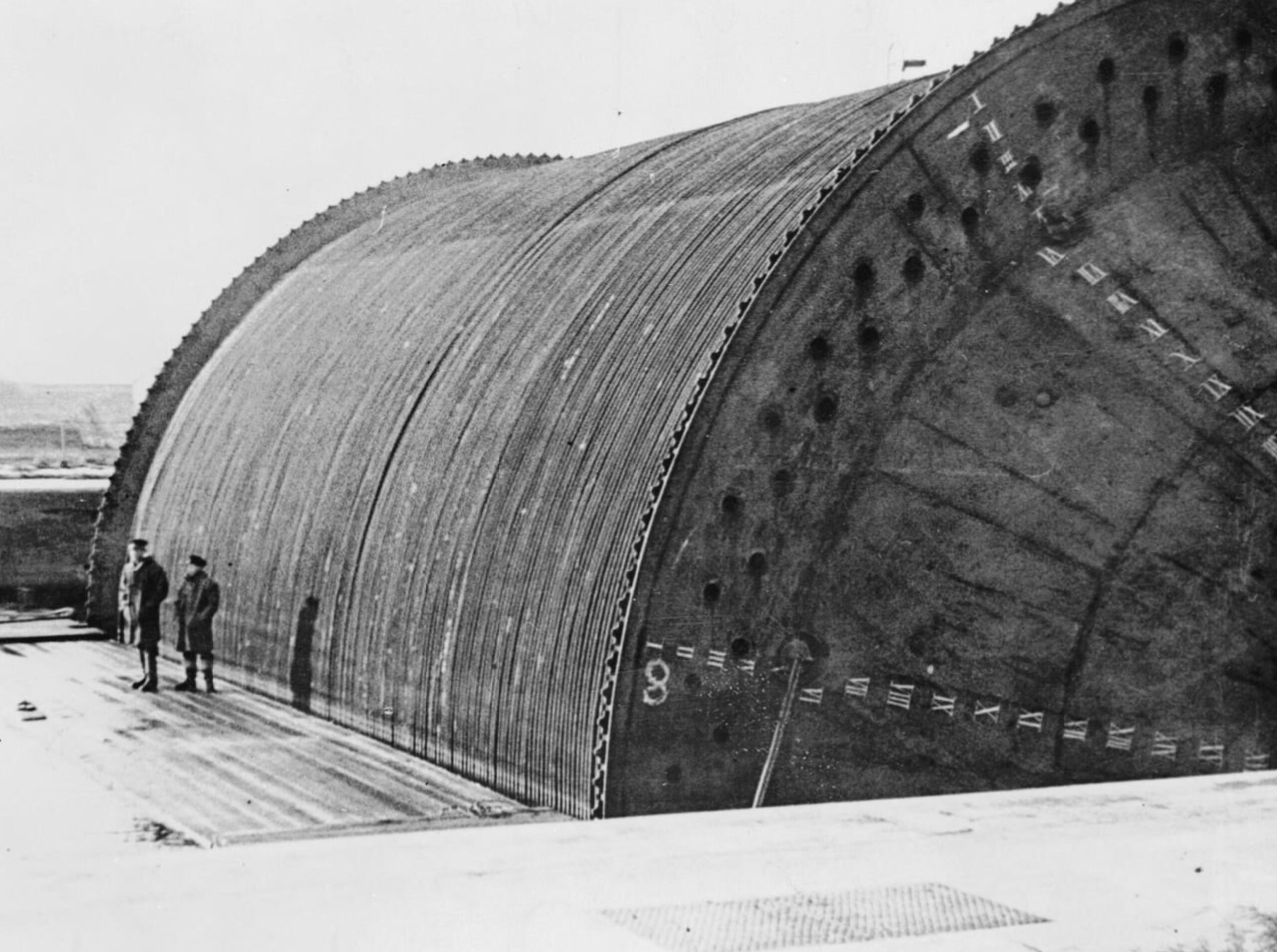

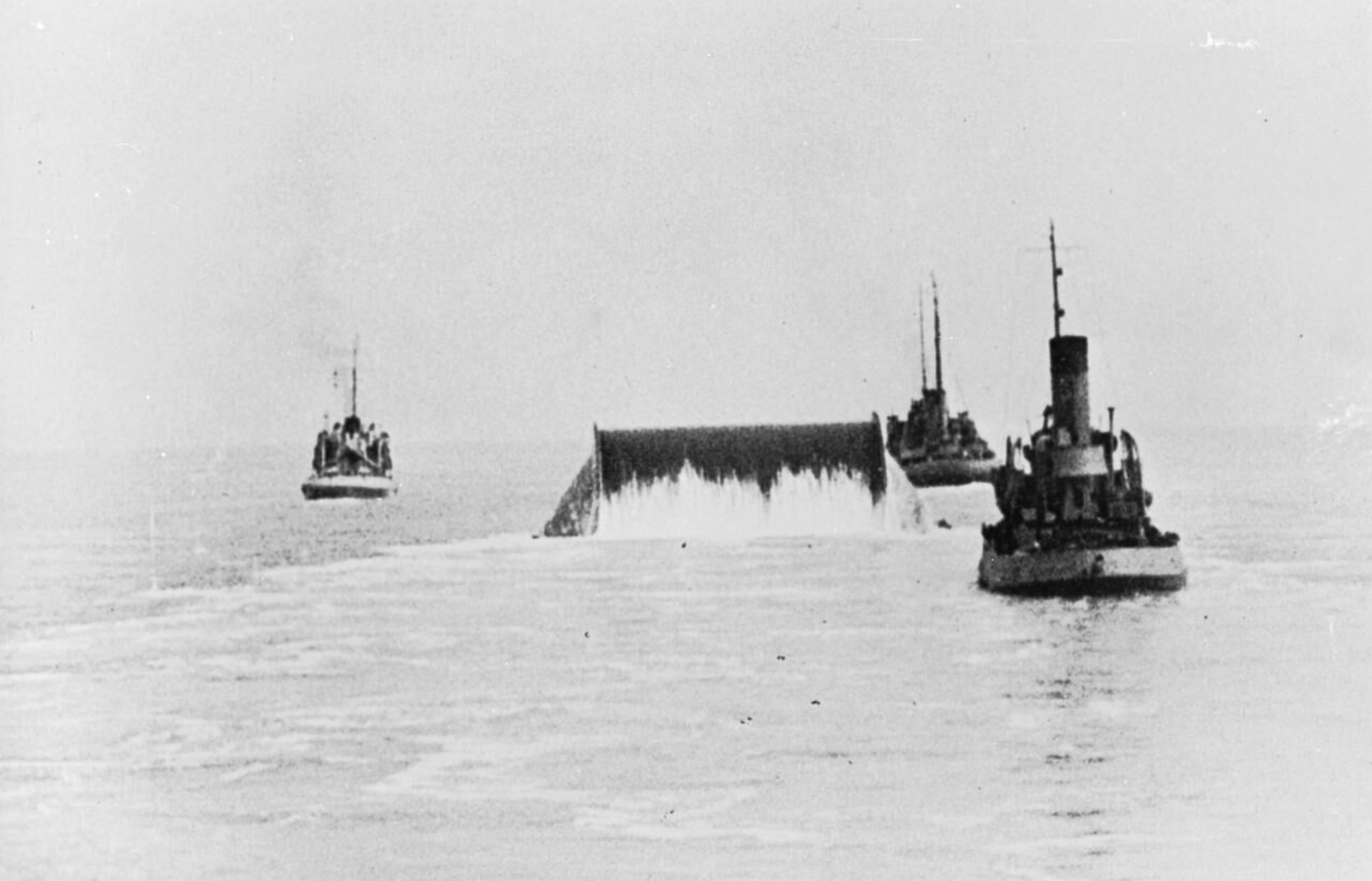

Two types of piping were used as part of Operation PLUTO. Cabling with lead tubing and armored steel wire, codenamed ‘HAIS,’ was one. The other, codenamed ‘HAMEL,’ took the form of welded steel piping that could be wound around a large diameter drum, referred to as a ‘conundrum.’ It was estimated that this type of pipe would be able to survive for up to six weeks within the Channel which, as Whittle indicates, was considered sufficient. HAIS and HAMEL pipes were each just three inches in diameter.

The pipes needed to traverse a vast distance. PLUTO was planned on the assumption that the Allied invasion of France would occur in the Pas de Calais, northern France, some 31 miles (50 kilometers) from England’s south-eastern coast. However, in 1943 it was decided that the invasion would in fact occur at Normandy.

The new location for the pipeline from here connected Cherbourg in Normandy to the Isle of Wight off England’s southern coast.

It was not until August 12, 1944, that the first PLUTO pipeline, codenamed ‘BAMBI,’ was laid by the Royal Navy. As part of BAMBI, HAIS cable was laid from Cherbourg to the Isle of Wight. The pre-existing Reading/Southampton GPSS mainland pipeline was extended to the Isle of Wight especially for BAMBI.

Work on the PLUTO pipeline was scheduled to begin on June 24. Delays were caused in part because the pipes themselves were easily damaged when laid.

But more significantly, BAMBI was delayed because of the military chain of events after the D-Day landings. Work on the PLUTO pipeline relied on the Allies capturing Cherbourg harbor intact in only eight days. This was a tall order, and the harbor was not taken until June 27. For reference, the assault phase of the invasion, known as Operation Neptune, ended just a few days later on June 30.

How successful was Operation PLUTO?

BAMBI didn’t supply any petroleum until mid-September 1944. When it did, it only supplied around 275 tons (250 tonnes) of petroleum per day. The first laying of a HAMEL pipe took place in late September.

In early October, work began on laying a shorter pipeline, codenamed ‘DUMBO,’ from Boulogne-sur-Mer to Dungeness on the Kent coast. Dungeness wasn’t close to any of the GPSS pipelines, so a connecting pipeline, roughly 71 miles long, was used to ‘plug’ Dungeness into the main supply line. The Boulogne-sur-Mer to Dungeness pipeline was only partially operational by late October, supplying just over 848 tons (770 tonnes) of petroleum per day. DUMBO went on to deliver higher supply numbers than this. Citing the official postwar history of oil supply, Whittle suggests DUMBO reached a peak flow-rate of just under 2,000 tons a day after Victory in Europe Day on May 8, 1945. Edgerton has the figure at roughly 3,300 tons per day. Clearly, DUMBO was more successful than BAMBI, but this was well after the Allied invasion of Normandy.

Much of Operation PLUTO’s allure no doubt comes from the ingenuity displayed by those who made it possible. In this sense, it mirrors the efforts of the Enigma code-breakers of Bletchley Park, notably the scientist Alan Turing, in making the seemingly impossible – or at least the improbable – a reality. In May 1945, Churchill himself suggested that Operation PLUTO was “a wholly British achievement and a piece of amphibious engineering skill of which we may well be proud.”

Ultimately, Operation PLUTO was less successful than the British authorities envisioned in 1942 and 1943. The average flow rate of PLUTO roughly equated to two large tankers a month.

As Whittle suggests, however, PLUTO should be seen within the wider context of the GPSS network. Throughout all of 1944, and for a short part of 1945, the largely unknown GPSS network carried more than 275,000 tons (250,000 tonnes) per month (tpm) – a quite astonishing volume.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com