South Korea is reassessing its earlier decision to not supply weapons to Ukraine, leading to a warning from Russia’s President Putin that it would be making “a big mistake” if it were to change its policy. While Seoul has so far condemned Moscow for its full-scale invasion of Ukraine and provided Kyiv with economic and humanitarian aid, it has stopped short of sending arms. An angry reaction from Putin — who recently returned from North Korea where he signed a mutual defense pact with leader Kim Jong-un — should come as no surprise. After all, access to South Korea’s burgeoning defense industry would be a huge deal for Ukraine, offering advanced equipment, and in significant quantities, opening up one of the last major untapped resources of arms for the war-torn country.

“South Korea, the Republic of Korea has nothing to worry about because our military assistance under the treaty we signed only arises if aggression is carried out against one of the signatories,” Putin told reporters. “As far as I know, the Republic of Korea is not planning aggression against the DPRK [Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the official name for North Korea].”

Speaking at a news conference in Vietnam today, Putin added: “As for the supply of lethal weapons to the war zone in Ukraine, that would be a very big mistake.”

“I hope that this will not happen. And if it does happen, then we will also take appropriate decisions, which are unlikely to please the current leadership of South Korea,” Putin said.

The news that Seoul is mulling sending lethal military aid to Kyiv surfaced in a report from the South Korean Yonhap news agency.

The agency cited South Korean National Security Advisor Chang Ho-jin, who suggested that the policy review had been driven by the mutual defense pact signed between Putin and Kim.

An official statement released by Seoul’s presidential office today also criticized the Moscow–Pyongyang pact, observing that it contravenes sanctions on North Korea:

“The government clearly emphasizes that any cooperation that directly or indirectly helps North Korea increase its military power is a violation of U.N. Security Council resolutions and is subject to monitoring and sanctions by the international community,” the statement said.

Interestingly, in April 2023 there had also been signs that Seoul was reconsidering its position on supplying arms to Kyiv.

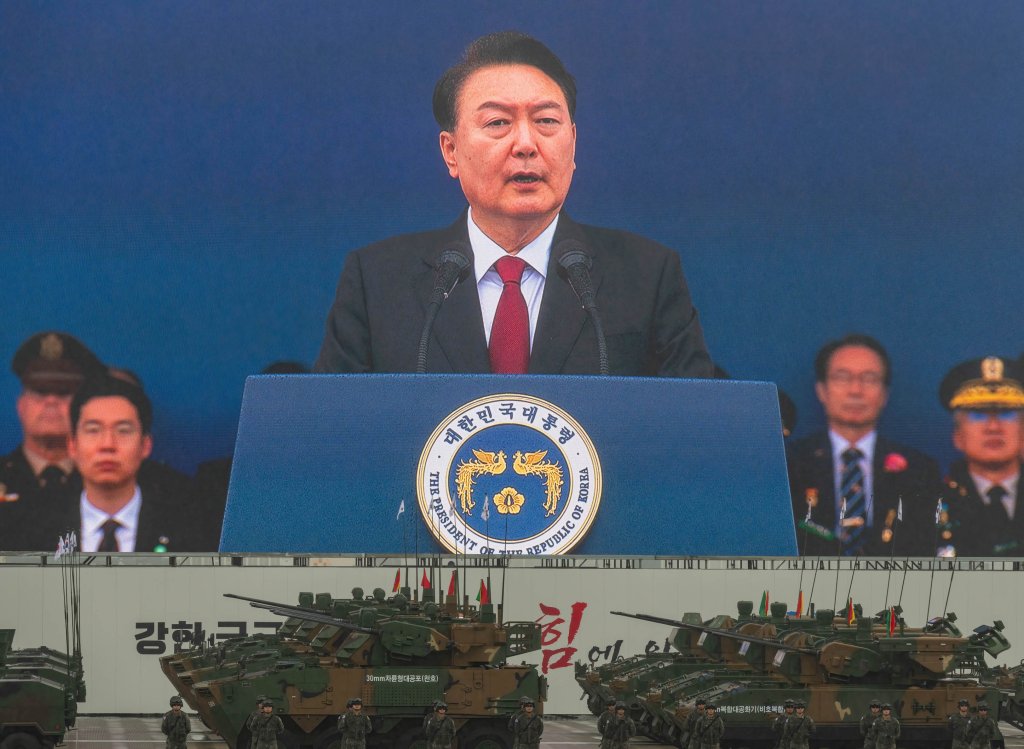

At that point, South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol had said that he would consider supplying weapons to Ukraine in the event of a major new attack against Ukrainian civilians. While the parameters of that were not made explicit, since then the Ukrainian population has been subject to repeated attacks, mainly by Russian drones and missiles, which have targeted critical infrastructure as well as cities across the country.

In response to that, former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, a close ally of Putin, threatened South Korea by suggesting that more and increasingly advanced Russian weapons could be delivered to the North.

“I wonder what the inhabitants of this country [South Korea] will say when they see the latest designs of Russian weapons in the hands of their closest neighbors — our partners from the DPRK?” Medvedev said in a post on Telegram.

Even without the new pact, under which Pyongyang and Moscow agreed to provide military assistance if either were ever attacked, Putin’s recent visit to North Korea further cemented the increasingly close relationship between the two countries.

As far as the war in Ukraine is concerned, the emergence of North Korea as a key ally for Moscow has ensured that Russian forces have received much-needed ammunition including artillery projectiles — reportedly numbered in the millions — as well as ballistic missiles, although these appear to have been used in a mainly evaluation capacity and with mixed results.

Meanwhile, there have long been concerns that the burgeoning military relationship between Moscow and Pyongyang is also providing North Korea with Russian expertise to help with the further development of its ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons — as well as other weapons and technologies.

On the other side of this equation is now the prospect that South Korea could start to provide vital weapons to Ukraine, unlocking a previously untapped and highly versatile source.

In recent years, South Korea has emerged as one of the world’s leading arms exporters and its weapons manufacturers span a notably wide range of technologies, from combat aircraft and helicopters to ballistic missiles and air defense systems to tanks and armored fighting vehicles and artillery.

President Yoon Suk Yeol has already laid out an ambition to become one of the world’s top four weapons suppliers, behind the United States, Russia, and France. The goal is not entirely unrealistic, however, with South Korea already being listed as the world’s ninth largest arms exporter between 2018–22, amounting to a 75 percent increase in its arms sales compared to 2013–17.

Ukraine has repeatedly been frustrated with the time that it takes to secure newly manufactured arms from Western nations — first in terms of gaining political approval, and second, waiting for the required industrial capacity to actually make those weapons.

South Korea offers something of a remedy to this problem, with active production lines operated by the likes of Hanwha, Hyundai Rotem, LIG Nex1, Hyundai Heavy Industries, and Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI). While these are primarily engaged in meeting a steady flow of domestic orders, they have demonstrated the scalability and flexibility to meet the demands of export customers, too.

At the same time, South Korean defense companies have shown a willingness to cooperate closely with export clients, including establishing assembly lines in foreign countries. Hanwha Aerospace, for example, has been tasked with establishing assembly lines for its K9 self-propelled howitzer in Australia, Egypt, and Poland.

This, too, is something that could be of considerable interest to Ukraine, as it seeks to tap into its existing defense industry while at the same time introducing more modern equipment to replace its Soviet-era inventory.

At one time, South Korean defense exports had very little in the way of success in Europe, but this has changed significantly in recent years, thanks primarily to Poland — also a close ally of Ukraine.

In 2022, in its biggest arms export deal ever, South Korea sold Poland 180 K2 tanks, 48 FA-50 light combat aircraft, and around 670 K9 self-propelled artillery pieces, worth upwards of $14.5 billion. What’s equally remarkable about this package is the speed at which it has been realized.

For example, the first 10 K2 tanks and 24 K9s were unloaded onto Polish docks only four months after the contract signature, with the first FA-50 aircraft being handed over in Poland within 10 months of the contract signature.

Few European or U.S. defense companies can match such a pace and this kind of commitment to fulfilling orders rapidly is something that Ukraine would surely be eager to benefit from as well.

For NATO customers, of which Poland is one, there is an issue arising from the fact that South Korean equipment generally doesn’t conform to NATO standards, making its integration with Western systems harder. On the other hand, Poland seems to have decided it was more important to get its hands on the desired weapons faster, and in greater numbers, for which South Korea’s impressive industrial capacity was found to be the answer. For Ukraine, with its combination of NATO, Soviet-era, and other weapons systems, a lack of standardization is hardly an issue, while industrial capacity most certainly is.

Aside from bigger-ticket items like those mentioned above, South Korea also offer a potentially very useful source of artillery ammunition, something that Ukraine has, at times, run dangerously short. In the meantime, multiple sometimes complex initiatives have been set up to try and source 155mm rounds, in particular, from around the world and get them into the hands of the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

As well as being one of the leading developers of artillery, South Korea has a significant capacity to produce the ammunition that arms these systems. The war in Ukraine has already driven South Korean ammunition production, with Seoul producing rounds for the United States, which are used to backfill stocks depleted by transfers to Ukraine.

In this way, Seoul has been able to help ammunition get to Ukraine, without having to deliver lethal aid directly to Ukraine. A change in policy in South Korea would allow such measures to be sidestepped, and for ammunition to be provided directly to Kyiv. At the same time, countries like Poland would also stand to benefit from expanded production lines, as would other importers of South Korean defense equipment.

There’s little doubt that South Korea’s defense industry is on the rise and its combination of technical know-how, flexible workshare arrangements, and rapid delivery schedules will continue to secure export orders for the country. If and how Ukraine fits into this remains to be seen, but there is very clearly a demand for various types of weapons from Kyiv that South Korea could potentially help fulfill. Now that the issue of South Korean arms transfers to Ukraine is apparently back on the table, the results could be highly significant.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com