The Russian Navy’s first new Project 23550 combat icebreaker has made an important step toward service entry. Unusually for an ice-breaking ship, the Ivan Papanin is armed, with the option to further increase its firepower in the future, including adding cruise missiles, This is a reflection of Russia’s preparations for potential future confrontations in the increasingly strategic Arctic region.

Completed at the Admiralty Shipyards in St. Petersburg, the combat icebreaker Ivan Papanin has now begun factory sea trials, according to a statement from the Russian Ministry of Defense, as reported today by the state-owned news agency TASS. An accompanying video shows the icebreaker being brought out of the shipyard and into open waters by a pair of tugs.

“In the course of this stage of tests the functioning of the propulsion system and onboard equipment systems will be checked,” a statement from the Russian Ministry of Defense read. “The commander-in-chief of the Russian Navy, Admiral Alexander Moiseyev, received a report on the ship’s readiness for trials from the heads of the relevant bodies of the military command,” the statement continued.

TASS also reports that the ship’s crew have already completed “comprehensive training” with the Russian Navy. The course is said to have involved “special programs … for training on the operation of equipment and weapons of ships of this project in Arctic conditions.”

Ultimately, the Ivan Papanin will join the Northern Fleet of the Russian Navy, although the latest report doesn’t provide an update on when this is due to happen. Formal commissioning had been planned for 2023, but is obviously running late, a situation that will be exacerbated by the demands of the war in Ukraine.

Launched in October 2019, the progress of the Ivan Papanin and future prospects for the Project 23350 class are something that TWZ has been monitoring for some time now.

What is especially notable about this class of ship is its ability to conduct combat missions, with a range of weapons potentially at its disposal. At the same time, the number of weapons fitted can apparently be scaled according to requirements.

Around the same time the Ivan Papanin was launched, Valery Polyakov, an adviser to the head of Krylov State Research Center, a state-run shipbuilding research and development group, provided his vision of Russia’s evolving plans for armed icebreakers.

“There will be icebreakers and ice-breaking ships, in other words, ships capable of moving at a sufficient speed through ice floes of [a] certain thickness. In fact, they will be armed icebreakers,” Polyakov said. “Where the ice is thin, there will be more weapons and the other way round.”

This would seem to have been a reference to the Project 23350 class and its potential to accommodate additional weaponry when the environmental conditions permit.

In its initial configuration, Ivan Papanin has an AK-176MA 76mm gun main gun in a turret on the bow. Based on statements from Polyakov, TASS reported in the past that the Ivan Papanin and other ships may eventually receive an AK-190 turret, also known as the A-190, armed with a 100mm gun.

An A-190 gun in action on an Indian Navy frigate:

There is also the option of fitting containerized launchers for Klub and Kalibr anti-ship and land-attack cruise missiles. A space at the rear of the vessel is expressly designed to accommodate these missile launchers, adding a powerful capability against a range of targets over a radius of between 930 and 1,550 miles, in the case of the longer-reaching Kalibr. In its report today, TASS suggests that the vessels can be optionally armed with eight Kalibr cruise missiles and/or Uran anti-ship missiles in two container launchers. The Uran is a smaller, shorter-ranged, subsonic anti-ship missile, closer in concept to the U.S. Harpoon.

Interestingly, this last point has parallels with discussions in the past about providing the U.S. Coast Guard’s future heavy icebreakers with a cruise missile capability, as well. The U.S. Navy now has its own containerized launch system, called the Mk 70 Expeditionary Launcher, which it has tested on crewed and uncrewed ships, as well as in a ground-based configuration. Derived from the Mk 41 Vertical Launch System, the Mk 70 can be used to fire multi-purpose SM-6 missiles and Tomahawk cruise missiles. The U.S. Army is in the process of fielding a closely related trailer-mounted containerized launcher as part of a system called Typhon.

The Project 23550s also have a helipad and a hangar at the rear, sufficient to support a Helix series helicopter. At least one artist’s impression shows a Ka-29 naval assault helicopter onboard, providing another option for engaging hostile threats.

Regardless of if or when the Ivan Papanin or other Project 23550s get additional weapons, the design signifies a major break from traditional icebreakers, which have not been schemed with real combat missions in mind.

Clearly, Russia expects these ships to have the capacity to conduct combat missions if required.

At the same time, the Project 23550 remains a capable icebreaker too.

With a displacement of 9,000 tons, the vessels are expected to smash through ice up to five and a half feet thick. While this is notably less than the 10 feet or so that a heavy icebreaker can deal with, the Project 23550 achieves this on a relatively light hull, and one that can also undertake combat missions.

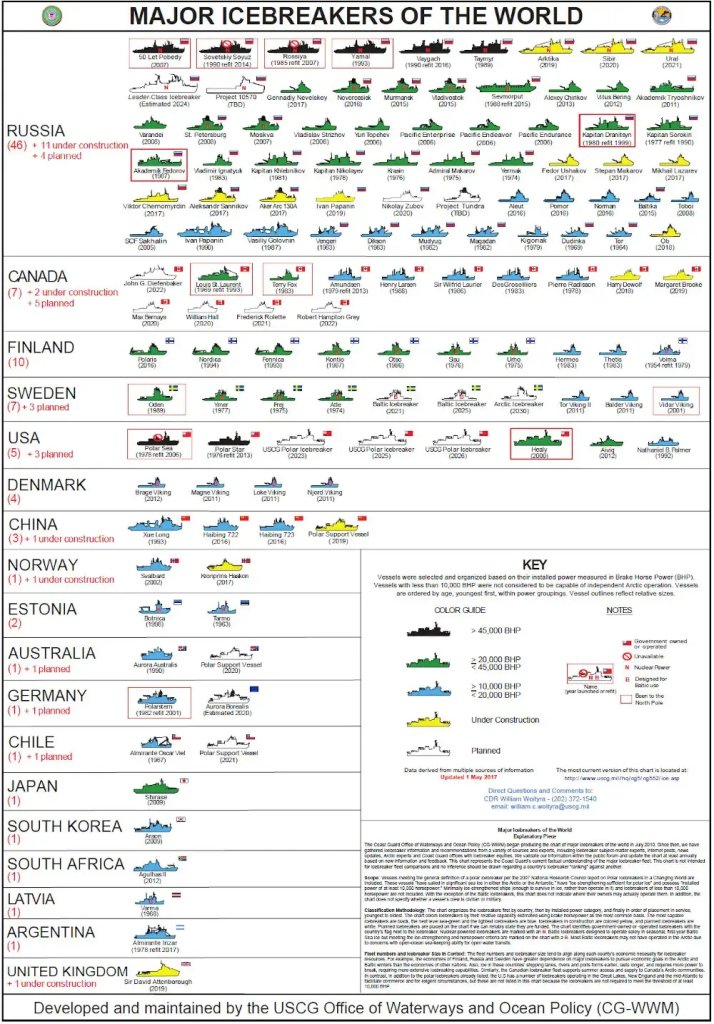

Meanwhile, the Project 23550s — at least three more of which are either under construction or planned — are just part of a large and growing force of Russian icebreakers and ice-capable ships, which today number around 40 vessels. Of the four planned Project 23550s, two are destined for the Russian Border Troops and may well be differently equipped.

Otherwise, Russia’s ships in this category include the new conventional Project 22600 and the enormous nuclear-powered Project 22220 icebreakers, as well as the ice-capable Project 03182 multi-purpose tankers. There have also been deliveries of other ice-capable support ships, namely the Project 20180 series, in recent years.

Potentially, some of these vessels could also be armed in the future, to create a larger combat-capable fleet.

All these developments point very clearly to the growing importance of the Arctic region for Russia — and the expectation that this could be a future combat theater.

Driven by global climate change, the strategic importance of the Arctic region has climbed steadily in recent years. As the polar ice cap retreats, this has increasingly opened up the region to greater activity and geopolitical competition.

Not only Russia, but also the United States, Canada, and to a lesser extent China, as well as others, are looking to expand their military presence in the Arctic — or at least the ability for their armed forces to operate there effectively.

In Russia, there has been intense activity in recent years to develop infrastructure in the Arctic to better support expanding deployments of ships, aircraft, and ground forces.

The Project 23550 ships are very much at the vanguard of these efforts, but they also highlight what is a growing gap in capabilities when compared with the United States.

Earlier this year, TWZ reported about this gap, after the U.S. Coast Guard said it was planning to buy an existing commercial icebreaker to help support its Arctic operations, a possibility that has been discussed since at least 2015.

At the same time, work on a new class of three Polar Security Cutter heavy icebreakers for the Coast Guard has suffered major delays, meaning that the first of these might not now be delivered until 2028 — the first had originally been due in service in 2024.

In the meantime, the service is left with one operational heavy icebreaker — the USCGC Polar Star — which is becoming increasingly troublesome in terms of operations and maintenance. Otherwise, the Coast Guard has a medium icebreaker, the USCGC Healy, which offers more limited capabilities.

Plans had been laid out in the past for the Coast Guard to buy three new medium icebreakers, but the timeline remains unclear.

The service is meanwhile acutely aware of the issues it faces in the Arctic and has said that it eventually requires a mix of at least eight to nine heavy and medium icebreakers to meet even its basic polar icebreaking mission requirements.

Despite the ‘pivot’ to the Pacific and the renewed emphasis on Russia’s activities in Europe, in the wake of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there’s little doubt that the strategic importance of the Arctic region is only set to grow. This factor is at the heart of the U.S. Coast Guard’s concerns about the limitations of its current icebreaker fleet.

For the time being, Russia possesses a fleet of icebreakers and ice-capable ships that is far larger than any of its rivals. What’s more, that fleet is growing, and while the Ivan Papanin may be delayed, it’s set to continue that path of growth.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com