A Baltimore-based startup has recently flown an experimental drone powered by a pulsejet engine, a type of powerplant that has few moving parts, in contrast to a conventional turbine, offering the promise of low-cost jet performance. Previously, the company, Wave Engine Corp., received U.S. Air Force funding to develop a decoy powered by a pulsejet — a powerplant best known for its infamous use in World War II. Meanwhile, the potential for the same propulsion technology to make it into other types of drones is something we have examined in the past and is becoming even more relevant given the increasing applications for expendable types.

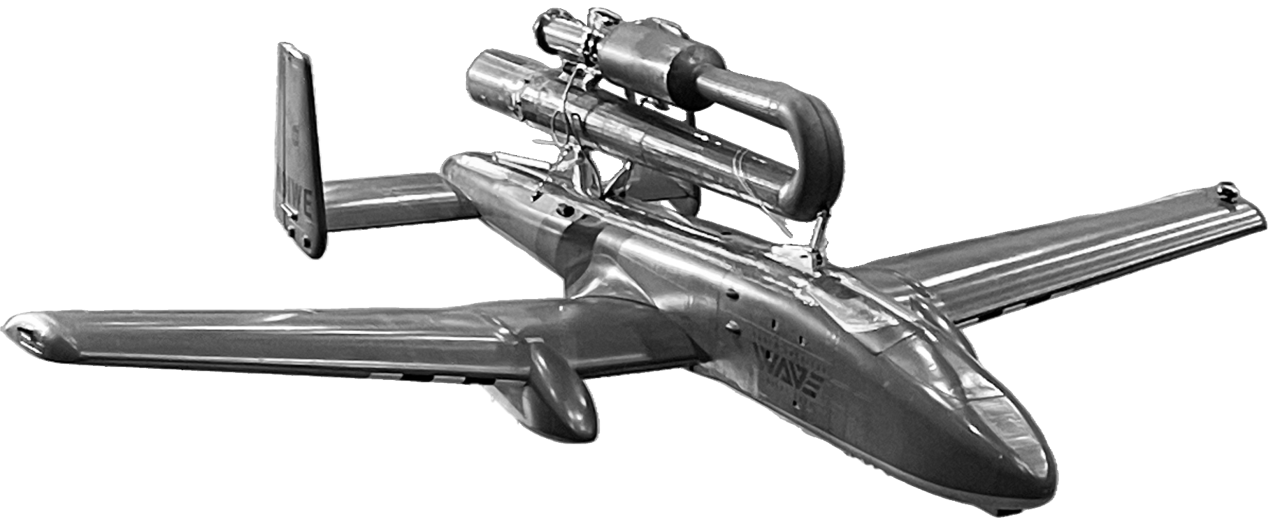

Wave Engine’s recent test involved a Scitor-D drone, a conventional takeoff and landing design that has a gross weight of around 100 pounds, a maximum payload of 20 pounds, and which appears to be a scaled-down copy of the A-10 attack aircraft design. The Scitor-D is part of a series of drones with external top-mounted engines, a configuration chosen to keep the vehicles simple and to minimize development and production costs.

For the demonstration flight, the drone was powered exclusively by a pulsejet developing more than 50 pounds-force of thrust (equivalent to more than 222 Newtons). The flight sequence began with a remote instant start followed by takeoff, climb-cruise, and landing.

In the wake of the test flight, Wave Engine announced its first productionized pulsejet, the J-1, also producing more than 50 pounds-force of thrust. Otherwise, the company told The War Zone that the J-1 is a lighter and more aerodynamic version of the engine used to power the Scitor-D.

Beyond this, the company also says it’s developed engines that can produce up to 250 pounds-force of thrust (equivalent to more than 1,112 Newtons). This would be sufficient to power a drone, missile, or aircraft with a gross weight of up to 1,000 pounds, Wave Engine says.

Wave Engine has meanwhile demonstrated “multiple” mid-air starts of its pulsejets and has operated its engines at airspeeds up to 200 mph, “limited only by the practical limits of the test facility.” Further tests of the Scitor-D are now planned, which the company says are “oriented around the continued expansion of the flight envelope and test conditions.”

The company has also demonstrated its pulsejets using various different fuels: gasoline/petrol (87 Octane), kerosene-based fuel (Jet-A/JP-8), and sustainable ethanol-based biofuel (E85).

In terms of fuel efficiency, the company has demonstrated thrust-specific fuel consumption (TSFC) levels under 2.0 pounds/pounds-force per hour, which it says rivals the efficiency of more complex and expensive turbine-based engines. Wave Engine combines its pulsejets with Full Authority Digital Electronic Control (FADEC), in which a computer controls engine performance, and this may well be key to achieving the stated levels of efficiency, as well as optimizing performance more generally.

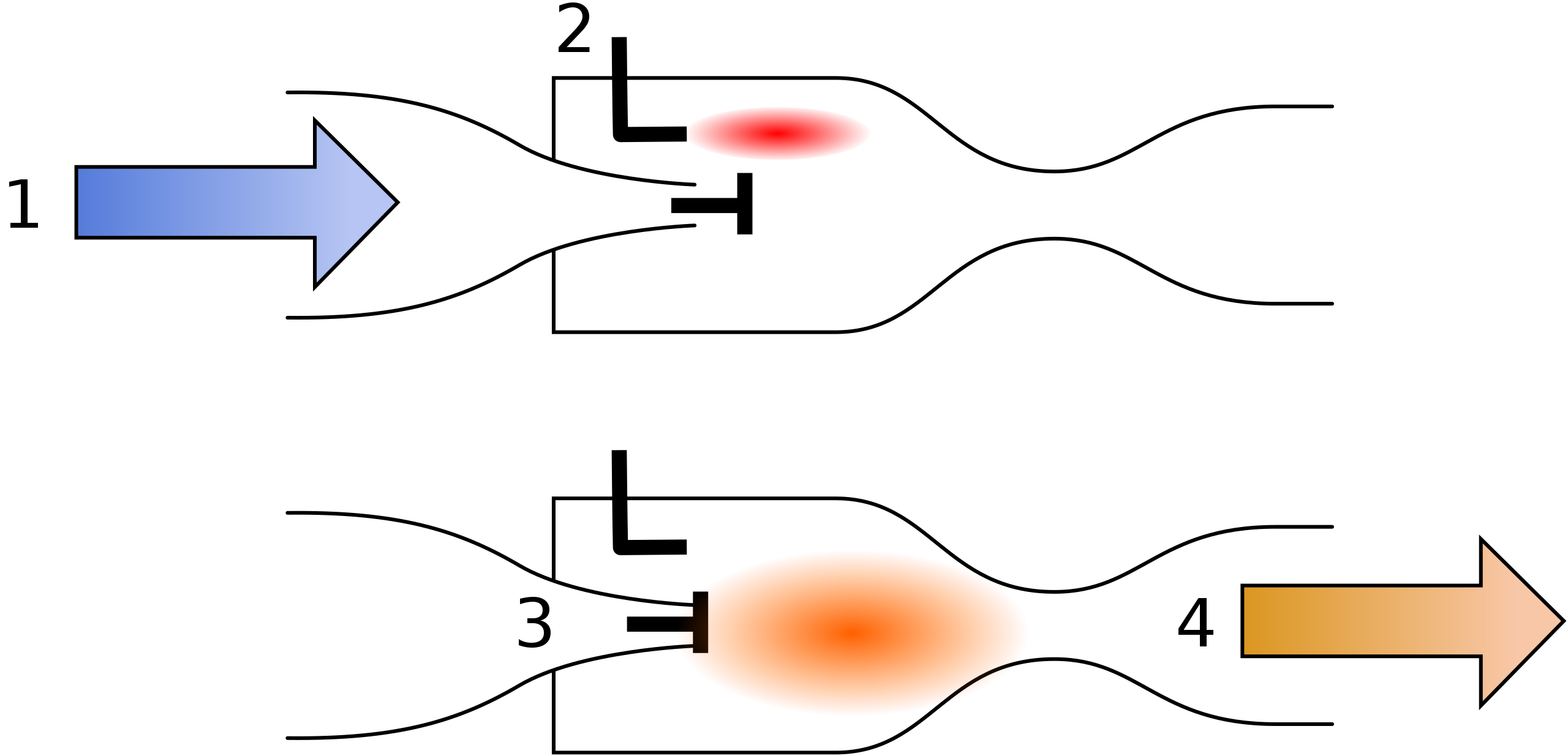

While you can read more here about how pulsejets work, as Wave Engine describes, a simple explanation is that they “operate using pressure waves instead of rotating machinery. Intermittent combustion inside a hollow tube produces pressure waves that push hot gases and produce thrust.”

The high speeds offered by pulsejets are also a factor in their favor, especially when compared to the propeller-based powerplants otherwise frequently found on many smaller military drones.

“We continue to push the performance and flight envelope,” said Daanish Maqbool, Wave Engine’s CEO, in response to the Scitor-D demonstration flight. “We have worked for years to harness the power of sound and fire, and we believe it is going to change the industry.”

The War Zone has reported in the past on the Versatile Air-Launched Platform (VALP), under which the Air Force Armament Directorate in 2021 awarded the startup a $1-million contract to develop and demonstrate a pulsejet decoy.

At the time, Wave Engine described VALP as “a multi-mission, air-launched vehicle that leverages the company’s proprietary engine technology to demonstrate high-performance, low-cost propulsion for future generations of high-performance aerial vehicles.”

Concept artwork released in 2021 showed a pair of VALPs being launched as decoys from an F-16 fighter. The pulsejet-powered decoys shown included a narrow and unusually deep forward fuselage, low-mounted swept wings, and a slender rear body possibly carrying a V-shaped tail unit.

While it wasn’t immediately clear how the VALP was intended to be used, as we stated at the time, a decoy in this class could employ various methods to confuse enemy air defenses, including replicating the flight profiles and signatures of friendly crewed aircraft, using electronic warfare jammers, or dropping chaff and other countermeasures.

Powered air-launched decoys are already in use with the U.S. Air Force, and other operators, including the ADM-160 Miniature Air-Launched Decoy (MALD), powered by a small turbojet engine and designed to spoof enemy air defense systems. Examples of the MALD have also been supplied to Ukraine for use in its war with Russia.

Prior to VALP, Wave Engine’s pulsejets attracted interest from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which in 2019 awarded a $3-million contract. This saw the company conduct flight demonstrations using a manned glider fitted with a pulsejet mounted above the fuselage.

As of today, VALP has progressed to the point that “a functional aircraft now exists,” the company told us. “We are in active discussions with government and industry partners to establish the next phase of the effort.”

While VALP was said to be intended “primarily as a decoy,” as we pointed out at the time, pulsejets have the potential for various other applications as well, especially where low cost is a driving factor, including a range of drones for applications other than air-launched decoys.

Cruise missiles could make use of pulsejets — effectively updating the concept that Nazi Germany used for its V-1 flying bombs, or “buzz bombs,” which were used in the final months of World War II and used the same basic type of powerplant.

Today, and especially since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the distinction between attack drones and cruise missiles has become increasingly blurred. Indeed, were the V-1 to be fielded now it would very likely be referred to as a long-range one-way attack drone.

Regardless, it’s certainly the case that the war in Ukraine has demonstrated a demand for low-cost, long-range drones, especially those that are intended to deliver an explosive payload in an expendible fashion. Russia’s enthusiastic adoption of the Iranian-designed Shahed series of drones has been paralleled by the rapid development of various homegrown Ukrainian one-way attack drones, offering increasingly long ranges.

With low cost and rapid producibility being key factors behind the feasibility of these kinds of drones, the potential suitability of pulsejet engines is worth considering, provided that they can offer — as Wave Engine claims — efficiency that can rival turbine engines.

One traditional drawback of pulsejets has been their relatively high noise signature, although for a one-way attack drone that’s not necessarily such a big concern.

In the United States, as well, there has, in recent years, been a growing focus on low-cost missiles in contrast to very expensive products like the AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) series. This line of thinking has led to programs such as Gray Wolf, an Air Force program for a low-cost cruise missile, powered by a miniature turbine.

The potential of larger numbers of air-launched munitions to be operated in networked swarms is also a growing area of interest for the U.S. military and provides another niche for lower-cost missiles, as well as decoys, working alongside more expensive precision-guided munitions such as JASSM. For applications such as this, a low-cost powerplant could also be especially attractive.

When asked about the current status of its pulsejet activities, Wave Engines told The War Zone that it is “seeing interest in our technology from the U.S. military and several foreign militaries.” Intriguingly the company also added that its “technology is currently a key component in an active U.S. Department of Defense program,” one that is separate from VALP. Further details were not provided, but it clearly indicates a broader interest in pulsejet technology within the Pentagon.

It’s unclear if we might start seeing a new generation of pulsejet engines powering drones and missiles, but with the U.S. military looking at buying large numbers of lower-cost guided weapons, the prospects could be good. If Wave Engines is successful in its goal of achieving an “order-of-magnitude reduction in the cost and complexity of jet propulsion,” then its pulsejets could have a very bright future ahead of them.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com