After years of delays procuring its own Medium Landing Ship (LSM) to ferry platoon-sized elements of Marines between West Pacific islands during a war with China, the U.S. Navy is now looking to existing, private-sector designs to potentially fill this capability gap.

The Navy halted its efforts to acquire the LSM last month, after an industry request for information (RFI) resulted in cost estimates that were beyond what the Navy and Marine Corps envisioned paying for the platform. Catch up on TWZ’s recent reporting on the acquisition travails that have plagued the program here. But earlier this month, Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) issued a new RFI to industry seeking an existing vessel design that could be retrofitted into a LSM that would require only minor modifications to fulfill requirements. It also seeks information from shipyards regarding the capacity for such an effort if they submit information.

The recently passed Fiscal Year 2025 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) “constrained” the Navy from procuring the LSM “as originally envisioned,” Rear Adm. William Daly, the Navy’s director of surface warfare, said Tuesday at the annual Surface Navy Association conference, which TWZ attended.

“But what it did was, the NDAA provided a unique opportunity to explore acquiring a non-developmental vessel to serve as the medium landing ship,” Daly said. “First in class, a great opportunity, recognizing the time-critical needs of Marine Corps littoral mobility.”

The new RFI, released on Jan. 6, seeks a landing ship that can conduct shore-to-shore beaching operations, while loading and unloading cargo directly onto a beach. It calls for a vessel that is shorter than 400 feet, with a 300-ton minimum cargo capacity. The request makes no mention of potential lethality or survivability upgrades that could be integrated into the existing platform.

It also seeks information on beach gradients that existing vessels could handle for offloading a full load onto the beach, along with speed and endurance data, how many have been built and how quickly more could come online.

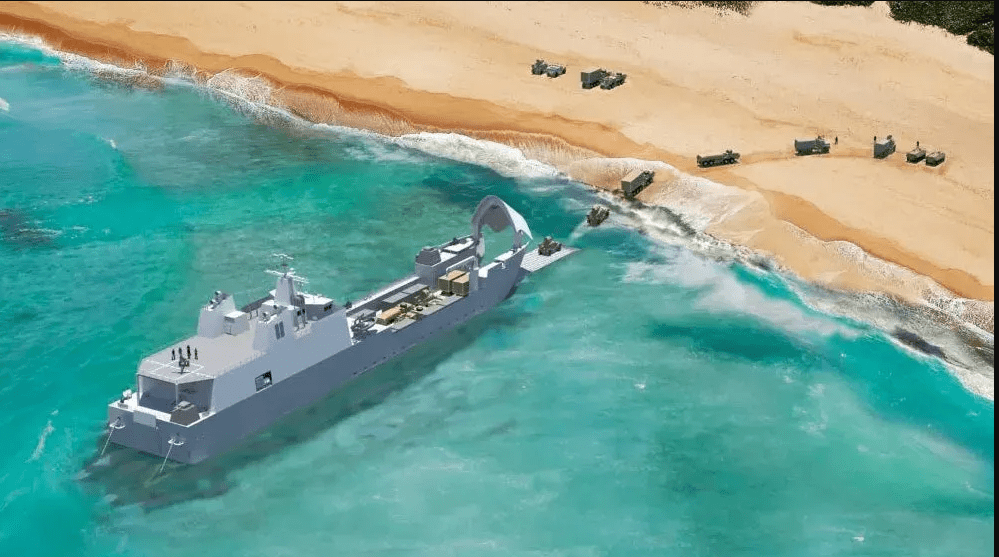

Formerly known as the Light Amphibious Warship (LAW) and also referred to as the Landing Ship Medium, the LSM is envisioned as delivering forces right onto a beach without any established port facilities. It would ferry mobile, platoon-sized Marine units to islands where they would fire anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM) at Chinese forces and collect data for other U.S. forces, among other tasks.

Those Marines would also work to deter opponents in situations short of actual conflict, while helping to control littoral areas and seascapes. Such missions would be conducted by the new Marine Littoral Regiments (MLR). The operations would occur within China’s striking distance, likely in the southern Japanese islands and in the Philippines, part of a sea-denial campaign spanning the South China Sea and East China Sea, analysts told TWZ in December.

LSMs are seen as a key mover of Marines under the Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) concept, which is a major component of the Marine Corps overhaul known as Force Design 2030 that seeks to ready the service for a war with China. Part of that original vision saw the Navy and Marines moving away from a laser focus on large amphibious assault and landing ships. TWZ has extensively reported on EABO and what it means for the Corps.

But opinions have differed on what the LSM should be, with the Navy wanting a more survivable vessel and the Marines looking to field the capability as quickly as possible, as some warn that China could invade Taiwan and prompt a U.S. response in the next few years.

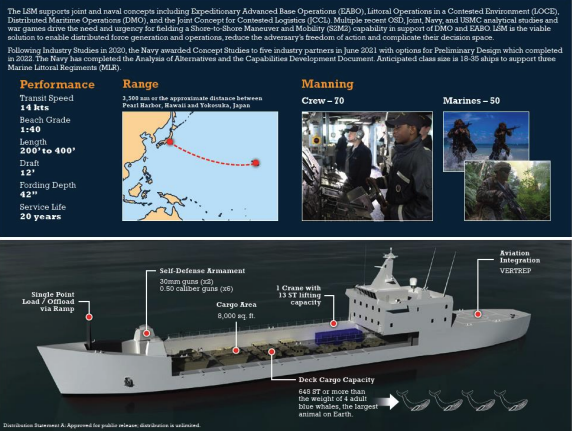

Under prior LSM concepts, the services called for between 18 to 35 LSMs that would range in length from 200 to 400 feet, with a 12-foot draft, each crewed by about 70 sailors, according to an August Congressional Research Service (CRS) report. The LSM would provide 8,000 square feet of deck cargo space and be able to carry up to 50 Marines and nearly 650 tons of equipment.

Per the original plan, the LSM was to also feature a helicopter landing pad, as well as two 30mm guns and six .50-caliber machine guns for self-defense. They would have a 14-knot transit speed, a cruising range of 3,500 nautical miles, and would be expected to serve for 20 years. The Navy’s latest RFI makes no mention of the sought-after ship design hosting such capabilities, and it remains unclear if they are still part of the Navy’s LSM requirements.

The Marines first introduced the idea of the LSM in 2020, but the program has suffered several stalls, with plans to acquire the first vessels initially pushed back to Fiscal Year 2023 and then to Fiscal 2025, as the Navy grapples with hefty bills for submarines and other needs, Defense News reported in 2022.

The Navy began receiving initial LSM concepts from shipyards and design firms in late 2020. By January 2024, the Navy was seeking proposals for the LSM, with Marine Corps officials saying they were on pace to procure in 2025 and deliver in 2029, according to the CRS.

Amidst these delays, the Marines have made do and already leaned on existing commercial and military capabilities that require little modification, according to the service. Those efforts have included Marines using stern-landing ships to inform the development of the LSM in the interim. A June 2024 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report warned that “existing commercial designs require significant modifications to meet LSM’s requirements,” and that none of the commercial designs assessed by the Navy had the required beachability or cargo fuel capacity.

“Although not optimal, such vessels will provide both operational capability and a sound basis for live experimentation and refining detailed requirements for the LSM program,” the Corps said in a 2022 update to Force Design 2030, a reorganization of the force that seeks to better prepare it for war with China.

The military has had some success buying commercial vessels and repurposing them for military use. A roll-on/roll-off cargo ship was modified to carry special operators and their gear and renamed M/V Ocean Trader, a job that TWZ reported on back in 2016. The ship has been something of a ghost since entering service, popping up in hot spots around the globe.

The British Royal Navy has undertaken similar efforts in recent years, and China has also used civilian ferries to move its amphibious forces and launch amphibious craft during beach invasion drills. Turning commercial ships into helicopter carriers is also something China’s training to do during a major contingency operation.

NAVSEA declined to tell TWZ the cost estimate that led the service to cancel its prior solicitation for the LSM early last month, saying it was unable to provide “source selection sensitive information.”

But USNI News’ Mallory Shelbourne first reported the latest LSM setback on Dec. 17, citing comments by Navy leadership.

“We put it out for bid and it came back with a much higher price tag,” USNI News quoted Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition Nickolas Guertin as saying at an American Society of Naval Engineers symposium last month. “We simply weren’t able to pull it off. So we had to pull that solicitation back and drop back and punt.”

Guertin noted that the service had what they thought was a “bulletproof” cost estimate, and a “pretty well wrung out design in terms of requirements, independent cost estimates,” USNI News reported.

The Navy’s proposed Fiscal Year 2025 budget requests show the first LSM would cost $268 million, but costs would average out to roughly $156 million by the seventh and eighth ship, according to the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

A U.S. defense official speaking on condition of anonymity told TWZ last month that initial plans called for each ship to cost between $100 million and $150 million, but that the Navy added features to meet their requirements, and that shot the price of each ship up dramatically. The Marines wanted a ship that was less exquisite and more numerous, according to the official.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) said in April that Navy estimates for the LSM’s cost have “varied widely.” CBO’s own analysis found the LSM could cost $340 million to $430 million per ship for an 18-ship program, an estimate it said reflects the range of full-load displacements – 4,500 tons to 5,400 tons – in preliminary designs that shipbuilders submitted to the Navy.

The Navy looking at existing ship designs for its LSM mission, and the program’s delays so far, highlight a longstanding tension between the Navy and Marine Corps. The Marines need certain maritime capabilities for amphibious operations. The Navy is tasked with moving those Marines, but must pay for the ships the Marines need. Similar debates have surfaced around the size of the larger-deck amphibious fleet in recent years as well.

The amphibious force is “not the favorite thing of the Navy to deal with,” Bradley Martin, a retired Navy surface warfare officer who spent two-thirds of his 30-year career at sea, told TWZ last month.

“I say this as a guy who spent a number of years on the amphibs,” said Martin, now a senior policy researcher with the RAND think tank. “The Marines aren’t very worried about how the Navy sustains ships, and the Navy hasn’t been really clear about what it takes to sustain ships. There’s been that disconnect.”

Navy and Marine Corps brass are united in sounding the alarm about China’s ascending military capabilities, and how Beijing could move to invade Taiwan as soon as 2027. The LSM is framed as a key enabler for Marines to contribute to a Pacific fight. But whether the Navy going back to the drawing board once again will get such a LSM out to the fleet in a quicker, more affordable way remains to be seen.

geoff@twz.com