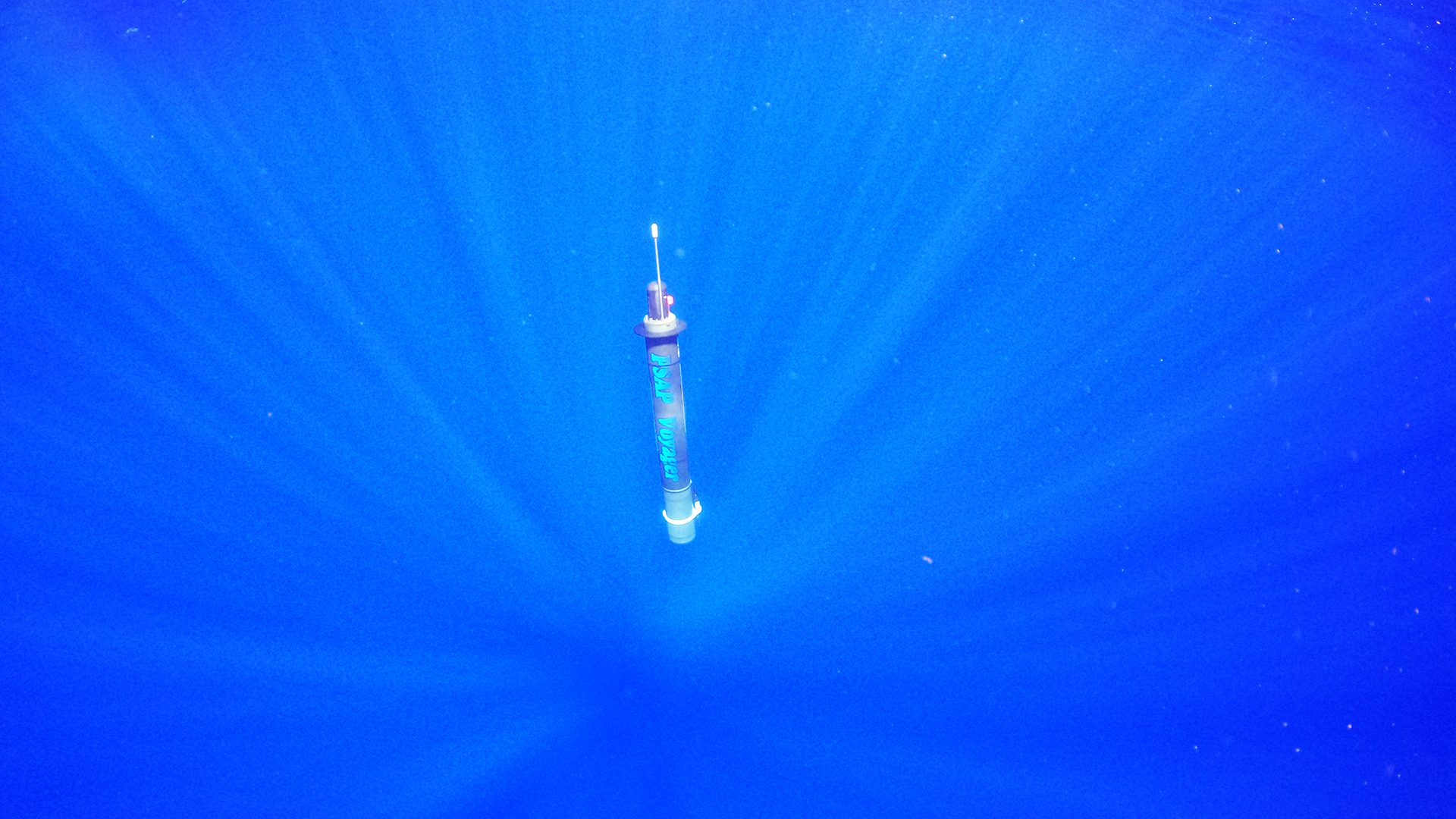

The Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) has helped develop an autonomous underwater float that can monitor and transmit oceanographic and underwater acoustic data near-indefinitely, and in near real-time. Known as the Persistent Smart Acoustic Profiler (PSAP) Voyager, it is powered by temperature differences in the ocean, providing enough energy to run its instrumentation for far longer than other non-wired undersea eavesdropping hydrophones currently in operation. Such an innovation could have big implications for undersea sensing and detection.

Capabilities like PSAP Voyager could prove doubly useful if operationalized for tactical means at a time when the U.S. Navy fleet is being eclipsed by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). Providing a highly flexible and rapidly deployable hydrophone system that can persist for long periods without any infrastructure could prove invaluable in this context.

The Navy announced PSAP Voyager’s milestone this week. Neither the service nor Seatrec, the manufacturer, responded to questions about the drone by TWZ’s deadline Thursday.

PSAP Voyager generates enough electricity via “ocean energy thermal conversion” to power onboard computing capabilities for processing the reams of data picked up by its passive acoustics, according to the company, which partnered with NPS in 2022 for the Voyager effort.

“The new PSAP Voyager’s ability to generate power leapfrogs previous generations of autonomous profiling floats that are limited by battery power and enables acoustic data to be collected in real time anywhere in the world’s oceans nearly indefinitely,” the company said last month.

PSAP Voyager testing off Hawaii late last year delivered troves of oceanographic and passive acoustic data that NPS undersea warfare, meteorology and oceanography students are now combing through, according to the school. The Navy’s announcement did not say whether Voyager will be put into operational use anytime soon.

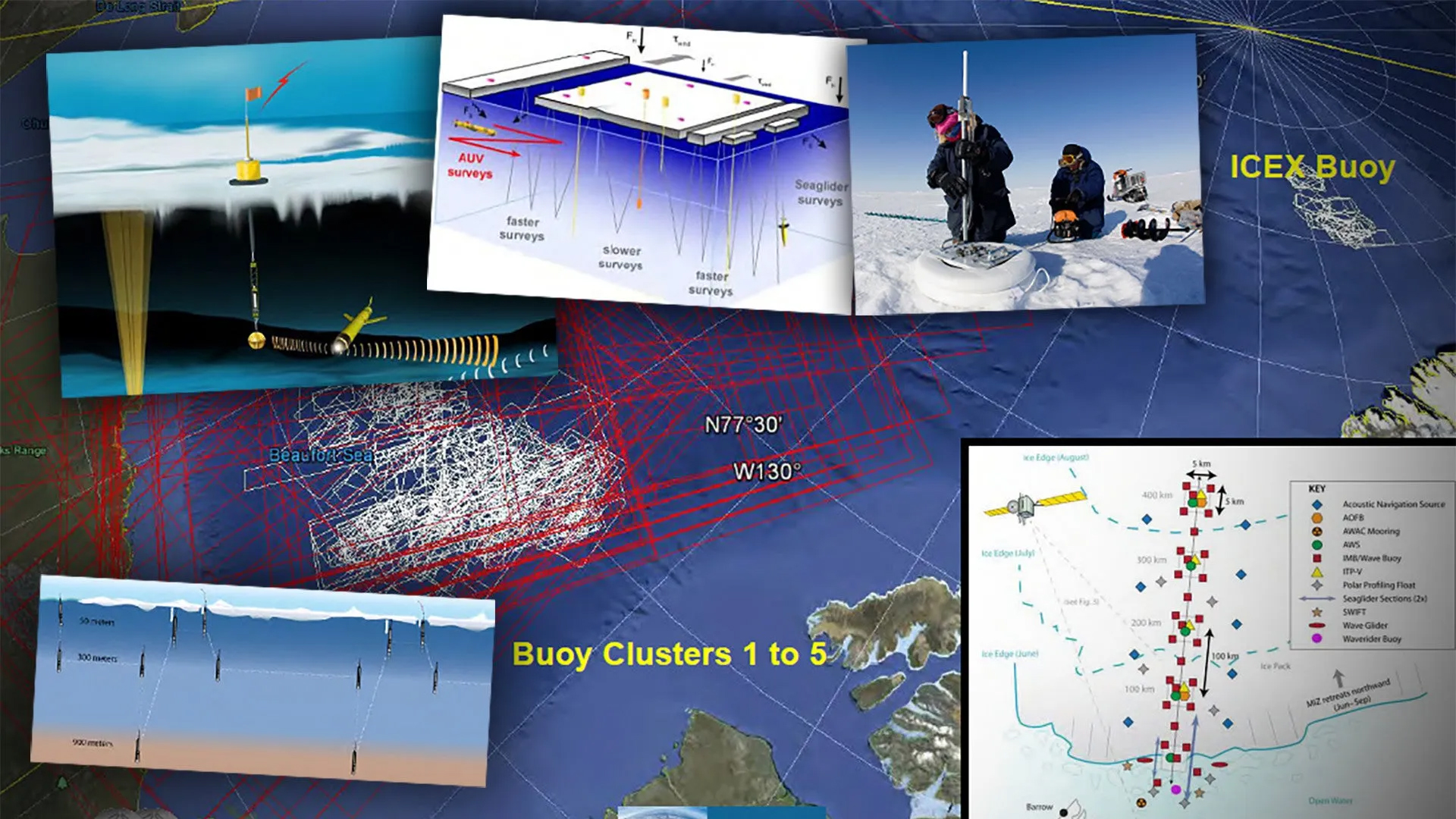

It remains unclear whether the Navy’s underwater monitoring force already relies on such thermal power conversion for any of its systems, and the silent service is generally secretive about its capabilities. Seatrec’s website indicates that it is working on projects for harvesting thermal energy for “low power Arctic sensors and data communications” for the Office of Naval Research (ONR), as well as long-endurance, fast-profiling floats for the Pentagon’s futuristic Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

A system like PSAP Voyager could be of big help to the undersea warfare community when it comes to persistent underwater surveillance. While it remains unclear precisely how far the PSAP Voyager can transmit its data or how it does so at all, crews could conceivably drop off a hydrophone at various locations, allowing the Navy to monitor underwater activity without a ship, submarine, or drone having to tend to the system regularly or without elaborate infrastructure on the seafloor.

“Passive acoustic listening has many operational and research applications in the Navy,” John Joseph, the principal investigator and faculty associate for research at the NPS, said in a statement last month. “The autonomy and long endurance of Seatrec’s PSAP Voyager provides an unprecedented opportunity to collect acoustic data in real-time for very long periods in remote areas without the expense and logistical tail of ship support.”

Traditional hydrophones are positioned in a towed array and dragged by a submarine or surface ship through the water. Others are situated at depth by a ship, or are placed on the seafloor and connected via fiber optic cable to ashore stations. But such deployments require dedicated vessels and other infrastructure to maintain those missions.

“Theoretically, PSAP can be deployed once, communicate its acoustic information to remote operators in near real time for limitless periods without requiring retrieval to offload data … swapping batteries or data storage, or replacement,” Joseph said. “These characteristics greatly reduce lifecycle costs of a continuous acoustic monitoring effort.”

PSAP Voyager’s arrival comes as the Navy has in recent years poured money into unmanned undersea vehicles and buoys, as well as networked communications and data sharing infrastructure, to support enhanced monitoring of environmental changes in the Arctic. But aside from such scientific needs, similar systems could also help the Navy monitor adversaries in the increasingly strategic region.

The Navy has also sought to develop other fixed, persistent, deep-water active anti-submarine surveillance systems. While the service has not provided many details about such efforts, the Affordable Mobile Anti-Submarine Warfare Surveillance System, (AMASS) would involve large sonar arrays attached to buoys that ships could drop in the ocean from inside a standard shipping container.

Go here to read TWZ’s reporting on those efforts, which have come as Navy brass continue to warn about increasing submarine activity from potential adversaries, particularly Russian subs operating more regularly off the East Coast of the United States.

Meanwhile, China has in recent years also developed undersea sensor networks that Beijing says are for scientific purposes, but that could be used to track foreign submarine activity in the South China Sea and East China Sea.

As previously reported by TWZ, the Chinese plan envisioned a number of unspecified sensors dwelling on the ocean floor. But unlike PSAP Voyager, those sensors were to be connected via optical cables to a monitoring and processing facility in Shanghai. The devices will be able to provide “real-time, high-definition, multiple interface, and three-dimensional observations,” state-run outlet CCTV reported in 2019. The U.S. had its highly classified SOSUS network of hydrophones on the seafloor around the globe during the Cold War, with elements of the program now being used for scientific research. Similar modernized systems remain and operate under classified programs today.

Regardless, the possibility that buoys based on PSAP Voyager’s technology could help the Navy rapidly deploy persistent underwater listening networks wherever they are needed is clearly a highly promising proposition.

Update: Feb. 7, 2025, 12 p.m. EST —

After publication of this report, we received additional information on the PSAP Voyager from Seatrec’s founder, Dr. Yi Chao. His comments are below.

On how the system communicates its data: “PSAP float has an antenna that can communicate with the Iridium satellites whenever it is at the surface.”

On its propulsion: “PSAP float has a buoyancy engine that can move the float up and down in the ocean. The buoyancy engine can change the float volume by inflating/deflating an external bladder (like a hot air balloon). While the weight of PSAP remains the same, increasing/decreasing its volume will make it lighter/heavier than the seawater, and therefore moving up and down.”

“PSAP can receive a command from the operators through satellite communications. The operator can instruct PSAP to dive to any depth between the surface and 1,000 meters, known as the parking depth. The parking time can also be specified before coming to the surface to transmit data to satellites and receive the next command. For example, PSAP is reporting data back to us every six hours.”

Click this link and select iF00002 to track PSAP Voyager’s real-time progress.

“It is currently programmed to dive down to 700 meters (taking about 2 hours to dive from the surface to 700 meters), park at 700 meters for about 2 hours, and coming back to the surface (taking another 2 hours). During the parking period, a passive acoustic hydrophone is turned on twice, about 10 minutes each listening period. The data is processed onboard by a Linux computer inside the PSAP float, and the processed data are then transmitted to satellites for further analysis.”

“There are two major breakthroughs for this PSAP Voyager enabled by Seatrec’s infiniTETM float, 1) energy harvesting from the temperature differences in the ocean to enable long endurance and persistent monitoring, and 2) onboard data processing to dramatic reduce the data size to enable satellite data transmission and reporting near real-time.”

Email the author: geoff@twz.com