The U.S. military isn’t currently interested in fielding kinetic and directed energy capabilities, such as laser and high-power microwave weapons, surface-to-air interceptors, and gun systems, for defending domestic bases and other critical infrastructure from rapidly growing and evolving drone threats. Instead, the focus is on electronic warfare and cyber warfare, and other ‘soft-kill’ options, at least for the time being.

Still often confusing legal and regulatory hurdles that limit how and when counter-drone systems of any kind can be employed within the homeland are key drivers behind the U.S. military’s current plans. Concerns about risks of collateral damage resulting from the use of anti-drone capabilities factor in heavily, too. This all, in turn, raises questions about the potential for serious gaps in the currently allowable but still largely non-existent domestic drone defense ecosystem.

U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) Deputy Test Director Jason Mayes spoke yesterday about these plans and related issues with a small group of reporters including from The War Zone at Falcon Peak 2025, a counter-drone experiment at Peterson Space Force Base. NORTHCOM is headquartered at Peterson, as is the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), and the two share the same commander.

“We are focused on [counter-drone] technologies that have potential, not saying they’re completely approved yet, but potential for use in the homeland, specifically,” Mayes explained. “So we’re not bringing out stuff that’s… like the kinetic kill [capabilities]… that you’re seeing over in CENTCOM [U.S. Central Command] and AFRICOM [U.S. Africa Command].”

Various tiers of drones present ever-growing threats on and off traditional battlefields. This is a reality that is not at all new at this point, but that has finally been rammed into the mainstream discourse thanks in large part to the ongoing war in Ukraine, as well as various crises in and around the Middle East. A series of still-unexplained drone incursions over Langley Air Force Base in Virginia over the course of several weeks in December 2023, which The War Zone was first to report on, is a particularly prime example of the potential dangers all of this poses to the U.S. homeland. We have reported for years now on other glaringly concerning incidents in and around the United States impacting military bases, training ranges, and warships offshore, as well as critical civilian infrastructure.

Several companies brought counter-drone systems to demonstrate at Falcon Peak 2025, many of which center on defeating or at least disrupting targets via jamming GPS and other RF signals. There are also others that utilize more novel capabilities, including systems designed to hijack line-of-sight control links between a drone and its operator and drones that can fire nets or stringy streamers at other uncrewed aerial systems in flight. While potentially deployable within the current regulatory framework, these systems have very clear limitations.

It is useful here to step back and think about the current counter-drone ecosystem from the perspective of tiered capabilities (and associated rules of engagement) starting at the very lowest end with systems intended to increase situational awareness, typically through passive signal detection and tracking. This is where a drone is detected and tracked via its own electronic emissions. The next step up is active sensors, generally radars, that can track the drone regardless of it emitting radio frequency energy or not. Both passive and active systems are often paired with electro-optical and infrared cameras to help with positively identifying targets.

Moving further up the capability ladder, there are non-kinetic ‘soft kill’ defense options like electronic warfare, followed by directed energy weapons like lasers and high-power microwaves, and finally more traditional kinetic effectors like drone-hunting drones, anti-aircraft guns, and surface-to-air missiles. There are some outlier systems like drones that might fire things like nets, streamers or goo, or use electronic pulses to disable a drone, which fall somewhere near the same category directed energy.

“There are kinetic options…. They’re just not here,” NORTHCOM’s Mayes said. “Many of them [existing counter-drone systems] do have the ability to integrate with a kinetic type [of capability]. …. But again, it’s not something we were super interested in that regard.”

He highlighted the 20mm Vulcan cannon-armed Centurion C-RAM (Counter-Rocket, Artillery, and Mortar) and the Coyote counter-drone interceptor as being among such capabilities in U.S. military service now.

“They’re not appropriate for the homeland,” Mayes added.

When it comes to discussions about domestic drone defense within the borders of the United States, the point here about appropriateness is perhaps more important than any discussions about specific capabilities. A multi-faceted layered defensive architecture featuring various components from the aforementioned tiers would be the best for providing a broad scope of coverage against uncrewed aerial threats.

“So that’s the obstacle, right? The policies and the legalities of being able to use the systems, absolutely,” Mayes said.

“Net capture would be a fantastic asset on an installation,” he continued, using that capability as one example. “But it’s semi-autonomous, flying over top of people, capturing drones… and then you get into the engagement authorities for all that stuff when you talk 130i and all that, right?”

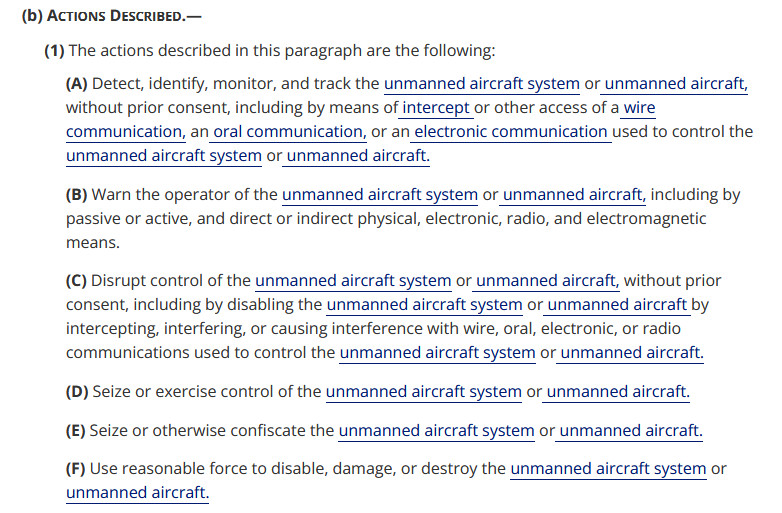

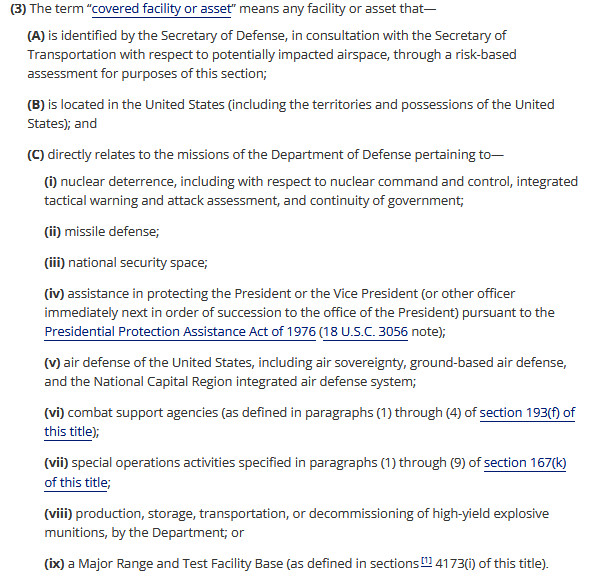

“130(i)” here refers to that subsection of Title 10 of the U.S. Code (10 USC 130i), which covers current authorities for the “protection of certain facilities and assets from unmanned aircraft.”

Under 130i, the U.S. military has the authority to take “action” to defend against drones including with measures to “disrupt control of the unmanned aircraft system or unmanned aircraft, without prior consent, including by disabling the unmanned aircraft system or unmanned aircraft by intercepting, interfering, or causing interference with wire, oral, electronic, or radio communications used to control the unmanned aircraft system or unmanned aircraft” and the “use reasonable force to disable, damage, or destroy the unmanned aircraft system or unmanned aircraft.”

At the same time, the statute as it currently exists stipulates that “the Secretary of Defense shall coordinate with the Secretary of Transportation and the Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration [FAA] before issuing any guidance or otherwise implementing this section if such guidance or implementation might affect aviation safety, civilian aviation and aerospace operations, aircraft airworthiness, or the use of airspace.”

There are notable caveats about the “covered facility or asset[s]” the law applies to, as well. A specific list provided in the statute is focused largely on top-tier national security sites and assets, including those related to nuclear deterrence, protecting the President and Vice President, the nation’s air and missile defense networks, and space launch activities. The U.S. military does also reserve its inherent right to act outside of this authority in self-defense.

Despite efforts in recent years to expand domestic counter-drone authorities across the U.S. government, 10 USC 130i, as well as other legal and regulatory frameworks, continue to impose significant limitations on how and when assets can be deployed and employed. U.S. Air Force Officials at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in North Carolina specifically cited 10 USC 130i as impacting their decision to explore installing entirely passive physical counter-drone defenses. Authorities at Langley Air Force Base are also looking into improving their defenses against uncrewed aerial systems by adding nets to open-ended sunshade-type shelters. The War Zone was first to report on both of these developments.

NORTHCOM’s Mayes highlighted how these issues are impacting plans to expand the use of even electronic warfare capabilities.

“Given the impact of GPS denial, just across infrastructure and all that stuff, it is a very, very difficult capability to get permissions to utilize” even for limited and heavily structured test events like Falcon Peak 2025, Mayes explained. Planners for the experiment were presented with the need to provide 30 to 45 days of lead time to unspecified agencies to get the required approval.

“Once we started talking to them and telling them, you know, if this were a real-world scenario where we are actively trying to get capability into an installation in a prolonged incident of some sort, right, we don’t have 30-45 days,” Mayes said. “And we said, this is a data point that we’re actually trying to collect in the process … how quick can we move this through, so that an installation commander that has concerns over what’s happening has the ability to flip the switch on some of these GPS denial capabilities to protect his assets, right?”

“I think, in real-time, we would probably be able to do it very quickly,” he added, but also highlighted the importance of increased coordination with agencies outside of the Department of Defense on counter-drone issues, which NORTHCOM says it is working on.

The drone incursions over Langley last December, especially, have highlighted the importance of being able to rapidly respond to such incidents. There are other past incidents that provide evidence of difficulties in quickly reacting to potentially malicious domestic drone activity. For instance, we know authorities were still in the process of approving the deployment of a domain awareness-type counter-drone system days after multiple still-unexplained drone incursions over the Palo Verde nuclear power plant in Arizona in 2019. The FAA also only imposed temporary flight restrictions around Air Force Plant 42, a top hub for advanced aerospace development work including on the B-21 Raider stealth bomber, in August of this year after months of drone incursions there. These are events that The War Zone again was first to report on.

Mayes also stressed the need for greater clarity on existing authorities to make sure U.S. commanders know what options are available to them and are willing to employ them without fear of inadvertent repercussions.

“There’s a lot of policy, and there’s some, you know, I wouldn’t call them gaps, per se, but there’s some areas where you’ve got one policy saying one [thing], another policy saying another, and the parts where they cross over get a little blurry.. and just confusing,” Mayes said, noting that this applies to internal U.S. military policies, as well. “So I think we need to solidify all that.”

“I think we need to clarify it [the policies] a little bit and establish a better understanding of that at the installation commanders level, who’s responsible for this, right, so that they feel, you know, a little more comfortable in telling their troop[s], yes, we need to pull that [drone] down,” he added.

Even if counter-drone policies are clarified and solidified, and authorities get expanded, there are still other concerns at play, especially when it comes to collateral damage. Shooting something down with a gun-based system or a surface-to-air missile carries inherent dangers of projectiles or interceptors, or debris from them, falling onto innocent bystanders below. The aforementioned Centurion C-RAM fires specialized self-destructing ammunition to reduce these risks. The drone, or what is left of it, which could include undetonated explosive warheads or other potentially hazardous payloads, would also fall to Earth in an uncontrolled manner after any such engagement.

Maybe even more importantly is that these weapons do fail and they are packed with high explosives and traveling at high speed, which could cause very unpredictable harm to people and property in a large potential impact area. Then there is the idea that you have to know exactly what you are shooting at, and that can be harder than it sounds when dealing with strange objects in the sky, especially in populated areas where civilian air traffic is dense. Making the call to shoot down an object over the U.S. is an incredibly complex task that never actually occurred until recently.

The U.S. military’s decision to shoot down a Chinese spy balloon in 2023 only after it had passed out over the Atlantic, as well as the downing of three other still-unidentified objects that year in U.S. and Canadian airspace over water or very sparsely populated areas on land, underscores these risk assessment considerations. The War Zone highlighted these issues at the time.

It is worth noting here that the U.S. military does have traditional gun-based air defense and surface-to-air missile systems arrayed around Washington, D.C., as well as various counter-drone systems. Details about the rules surrounding their employment are limited, but might help provide something of a model for deploying and employing expanded domestic anti-drone defenses. The U.S. military has also at least explored the idea in recent years of re-establishing a network of traditional surface-to-air missile sites to defend the homeland from various air and missile threats, which would have had to have touched on many of the same kinds of policy questions.

At the same time, even lower tiers of counter-drone weapons, such as lasers and high-power microwave systems, can create dangerous or otherwise serious collateral effects.

“I think that we could get to a point where we have approval for that here in the homeland,” Mayes said of laser directed energy weapons for counter-drone use. “The biggest thing right now is the impact of the laser when it moves beyond its target. You know, how far is it going? What’s that going to do? How long does the laser need to remain on target before it begins to inflict damage and so on, right?”

Mayes raised questions about whether the laser beam could impact aircraft or even satellites passing by, as well as things on the ground like “hikers up on a hill.”

The video below shows a test of a U.S. Navy shipboard laser directed energy weapon capable of being employed against drones.

“You have issues sometimes, when it comes to [high-power] microwaves, that, you know, emitting those out into an area, especially a populated area, it could become a problem, even if it’s physically okay for the population,” he added.

Omnidirectional electronic warfare jamming, whether of GPS or other RF signals, presents its own issues. It has the potential to disrupt nearby communications and RF-based instrumentation, including ones that drone defenders themselves might be utilizing to try to coordinate and do their job. Civilian frequencies could also be impacted, causing unwanted disruptions. Counter-drone jamming ‘guns’ that offer highly directional fields of fire have proven popular in part because of this reality, although their efficacy is spotty.

All of this in turn prompts questions about the potential for gaping capability and capacity gaps in the kinds of drone defense architecture the U.S. military is looking at currently. Even under the best circumstances, essentially relying on electronic warfare alone as the means of actually defeating or disrupting potentially hostile drones presents clear limitations. GPS guidance is already passive, presenting RF detection and engagement challenges, and further advances in autonomy, which are steadily proliferating, could further limit the utility of certain electronic warfare capabilities. Even today, commercial drones can be programmed to fly a certain route to a precise set of coordinates without anyone controlling them and they can remain aloft even when GPS is disrupted. This makes detecting and countering them with electronic warfare tactics very problematic if not impossible in certain scenarios.

Looking for novel low-collateral options, such as the net or streamer-launching drones, to avoid using more traditional kinetic effectors or directed energy weapons is already proving challenging. Mayes said that low-collateral drone-on-drone capabilities currently seem best suited to tackling what he described as “the careless and clueless,” or targets that, for whatever reason, keep a steady and relatively slow flight profile.

“Anytime that you are flying anything that’s potentially chasing something else, if the other thing is faster or more agile, you’re not going to catch it, right?” NORTHCOM’s Mayes said today. “Once you start getting into some of the faster [uncrewed aerial systems] like your FPV drones, your first-person view drones, these racing ones that are [capable of getting up to] 150-200 miles an hour, or drones that have been outfitted to be very agile, just the systems themselves are not able to keep up with that.”

“The demo that we did… [at Falcon Peak 2025] was more of a what we call defense mode, so kind of a point-point solution, like protection of a specific area or defending an area defending a point so the defense, defense mode allows the drone hunter to position itself much like a hockey goalie, soccer goalie, and keep a target from achieving its final destination,” Spencer Proust, Executive Vice President of Solution Engineering at Fortem Technologies, told The War Zone in response to related questions about the performance of the company’s net-launching DroneHunter uncrewed aerial system.

Attack mode would be much more like a dog fight, where it will chase its target, shoot it down, but when I say shoot it down, it actually has this particular system has two net guns on the front of it,” Proust added. “It is not designed to chase down FPV drones, but that’s why we have the [intercept-focused] defense mode.”

Fortem does also say right on its website that DroneHunter is more of an “effective back up layer to any antiaircraft missile defense systems” when it comes to faster and/or higher-flying threats.

It’s also worth noting that drone-on-drone combat has become commonplace in the conflict in Ukraine and there are claims that new defensive countermeasures are already emerging.

NORTHCOM, as well as the rest of the U.S. military, clearly continues to face significant hurdles in establishing domestic counter-drone defenses. At the same time, these issues are not new, nor are the threats, and the U.S. government-wide lag in addressing them only continues to be more pronounced. Underscoring this is the fact that Falcon Peak 2025 is in no way the first such demonstration of potential capabilities. They have been going on for many years, often featuring very similar systems, with action even for the U.S. military’s deployed forces only really ramping up once drones were raining down on allied fighters in Iraq during the battle of Mosul. You can read more about this glaring oversight here and here.

In the meantime, drone threats continue to proliferate globally among state and non-state actors, including organized criminal groups. The barrier to entry to acquiring and employing armed drones, especially weaponized commercial types, is and has been low. To reiterate, these threats are real now and already exist in forms that could relatively easily overcome the limited array of drone defenses the U.S. military is currently looking at deploying domestically, especially if employed in large groups to say nothing of truly networked swarms.

As already mentioned, the world also now looks to be on the verge of major new technological milestones in the lower-end uncrewed aerial system space, particularly when it comes to more autonomous targeting, driven heavily by advances in artificial intelligence, as you can read more about in this War Zone feature.

Some of the responsibility for addressing these issues certainly falls to Congress, action from which would be required to alter things like 10 USC 130i or to establish new counter-drone legal frameworks. Legislators are clearly aware of this and a number of relevant legislative proposals have been put forward just in the past few months.

The work NORTHCOM is doing through Falcon Peak 2025 is clearly meant to reflect a new push to address now long-standing demand for counter-drone defenses within the homeland. However, the event has also underscored significant barriers that remain in fielding these critical capabilities domestically, to that point that lasers, high-power microwaves, and other kinetic effectors are not even on the table, at least for the time being.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com