War in ancient Greece was fought both on land and at sea; yet the naval side is arguably less well-known than its land-based counterpart. Who were the men who tried to make their city-states rule the waves more than 2000 years ago, and what was naval warfare like during that time?

In ancient Greece, a complex military system developed to win battles at sea; utilizing the efforts of oarsmen and marine soldiers alongside innovative and constantly evolving naval tactics and substantial technological developments. There was no specific ‘Greek’ navy — as indeed there was actually no ‘Greece,’ as we would come to understand it, during that time. What we know today as ‘Ancient Greece’ was actually a collection of more than 1,500 independent city-states (poleis, singular polis), spread across a geographic area generally consistent with that of modern Greece.

Each raised military forces to defend its interests both at home and abroad – some specialized in land-based armies, while others prioritized the development of powerful fleets, although many were able to maintain capabilities in both domains.

The earliest naval warfare in ancient Greece probably took the form of coastal raiding, organized by private individuals acting more in the form of pirates than any state-sponsored fleet. This type of raiding is documented in early Greek literature such as Homer’s Odyssey. The first naval battle may have taken place as early as 660 BC, according to the Greek historian Thucydides, although the first which can be reconstructed with any detail took place at Lade in 495 BC. From this point on, wars in Greece, whether intra-Greek or against foreign invaders, were fought on both land and sea – and the main warship used to do so was the powerful trireme.

The Trireme

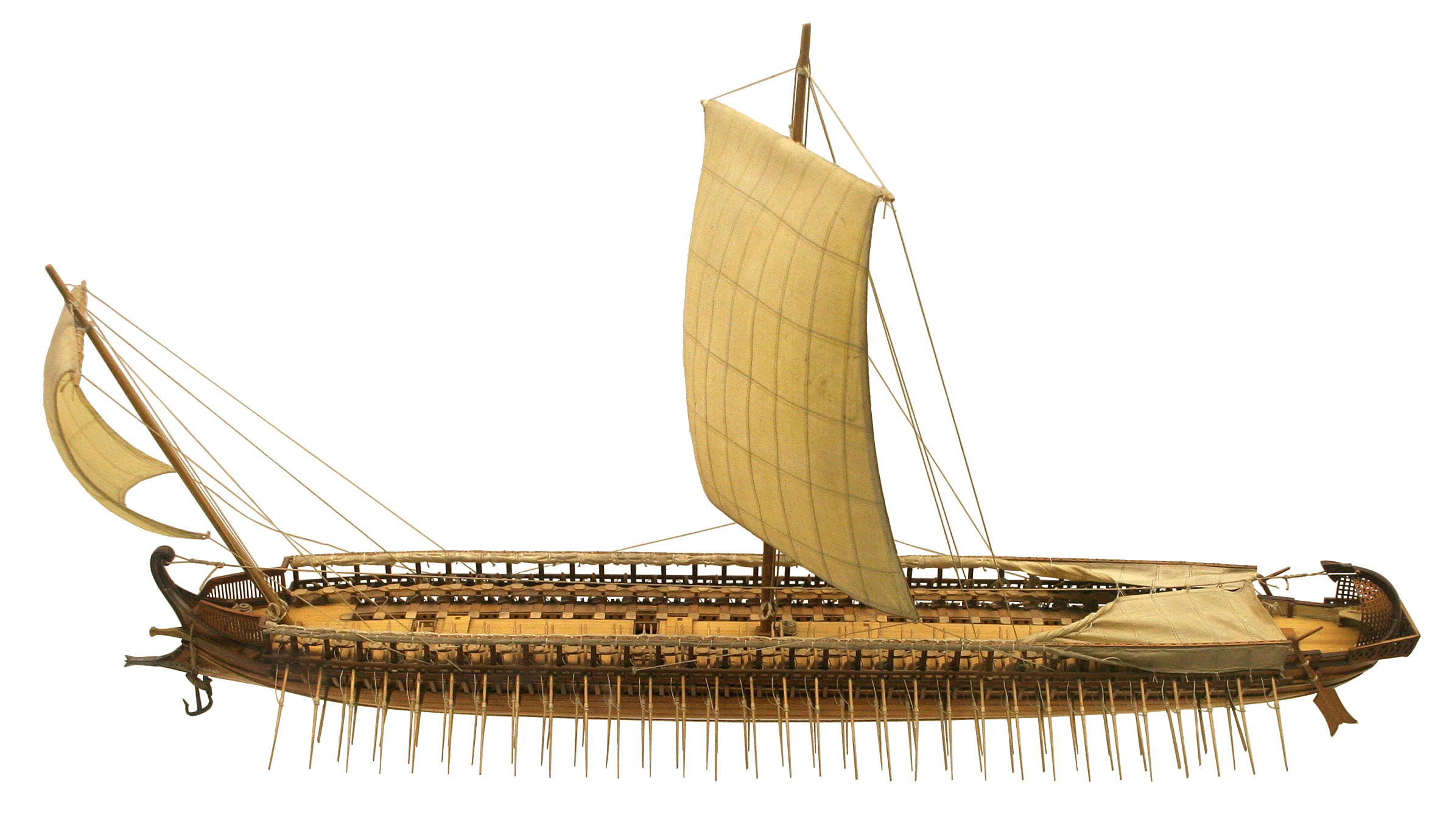

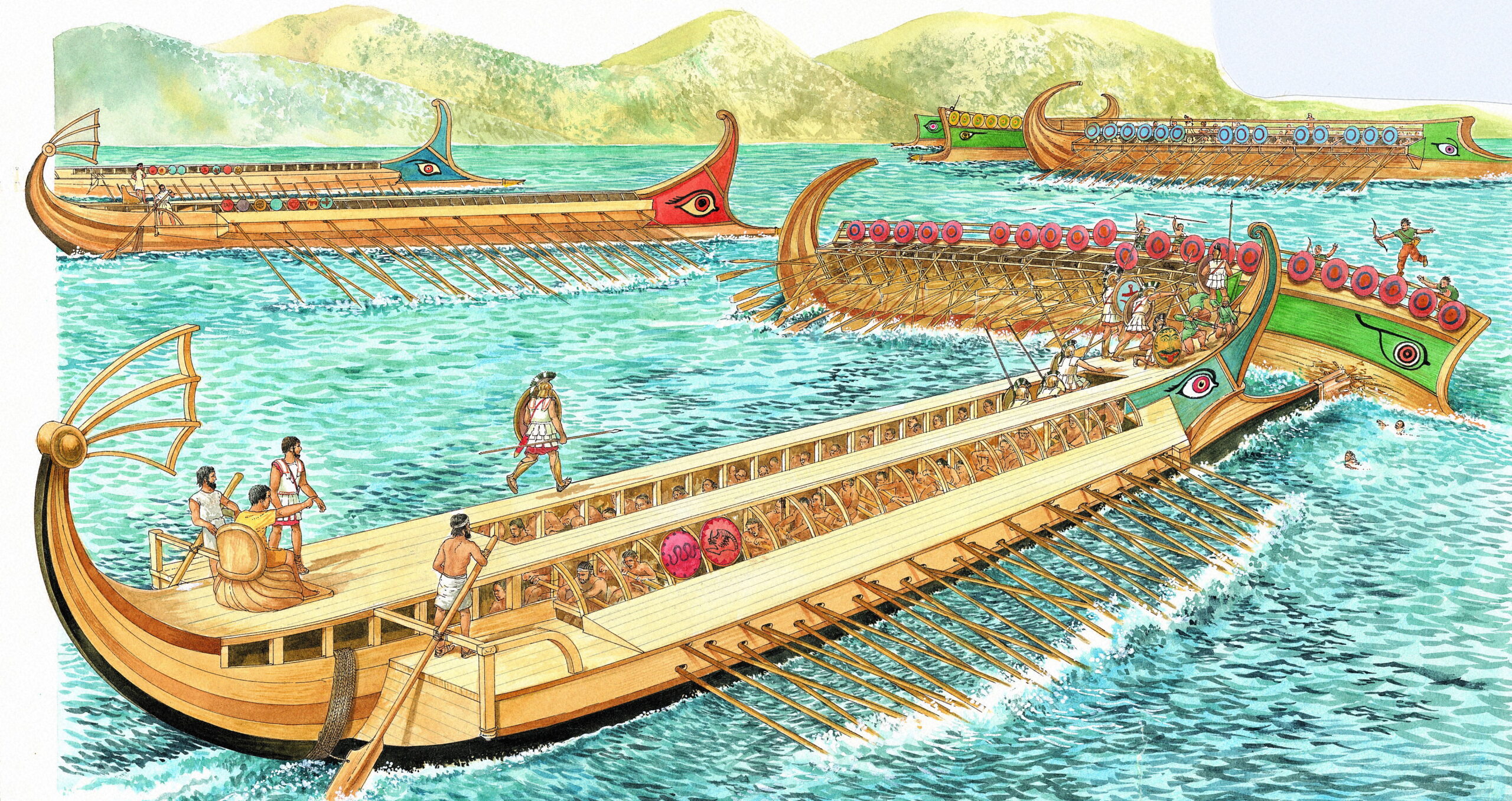

The classic vessel associated with ancient Greek marine warfare was the aforementioned trieres – better known by its Latin title, the trireme (the name that is preferred here) – which was named for the three ‘banks’ of oarsmen which powered its movement. Although oar-powered in battle, the trireme was also fitted with two sails for general seafaring.

The main weapon of the trireme was a bronze ram fitted to its prow, capable of penetrating the boards of enemy vessels and, if not sinking them, causing them to wallow to the degree that the crew was forced to abandon ship. They could also smash the oars of enemy vessels, rendering them ineffective. Several ancient Greek rams have been recovered from the Mediterranean; one example, housed in the Piraeus Archaeological Museum, vividly illustrates the vicious capability of these weapons.

Triremes were a marvel of engineering in their time, balancing the need for speed (and thus number of oarsmen) with the practicalities of keeping the vessel balanced and stable. Their low center of gravity provided additional stability whilst minimizing the risk of capsizing when maneuvering. These characteristics made triremes incredibly effective in battle, allowing them to perform sharp turns and rapid movements — although this did come at the cost of reducing their overall seaworthiness. Triremes were, however, vulnerable to even moderate swells, and in the rough seas of unexpected storms, entire fleets could be lost.

A fleet was a substantial financial investment. Triremes were expensive and labor-intensive to build, and many were commissioned by wealthy individuals as contributions to the state. If well-maintained, they could endure more than twenty-five years in service, although this required them to be dragged onto the shore overnight when possible, with the crew then ‘de-boarding’ for the night — leaving them vulnerable to surprise attacks.

The trireme dominated naval warfare in the Mediterranean from as early as the 7th century BC to the 4th century BC, after which it became increasingly superseded by larger vessels developed by the Carthaginians, the Macedonians, and the Romans (which could have double-figures worth of rowing banks). Nevertheless, with the right crew, a trireme was a warship with a lot of potential at sea.

The Crews – Oarsmen and Soldiers

An average trireme had a crew of around 200 men, mostly oarsmen, supplemented by a small number of more technical crew and marine soldiers, all of whom were paid for their service. A fleet was therefore a huge investment financially as well as in terms of manpower.

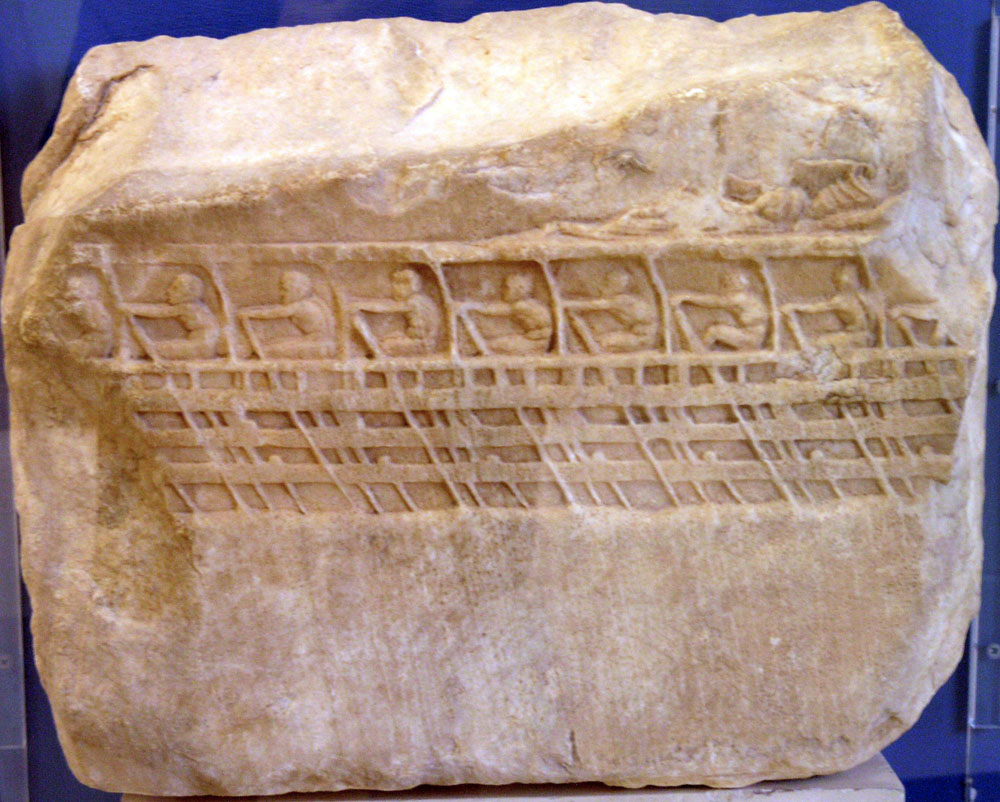

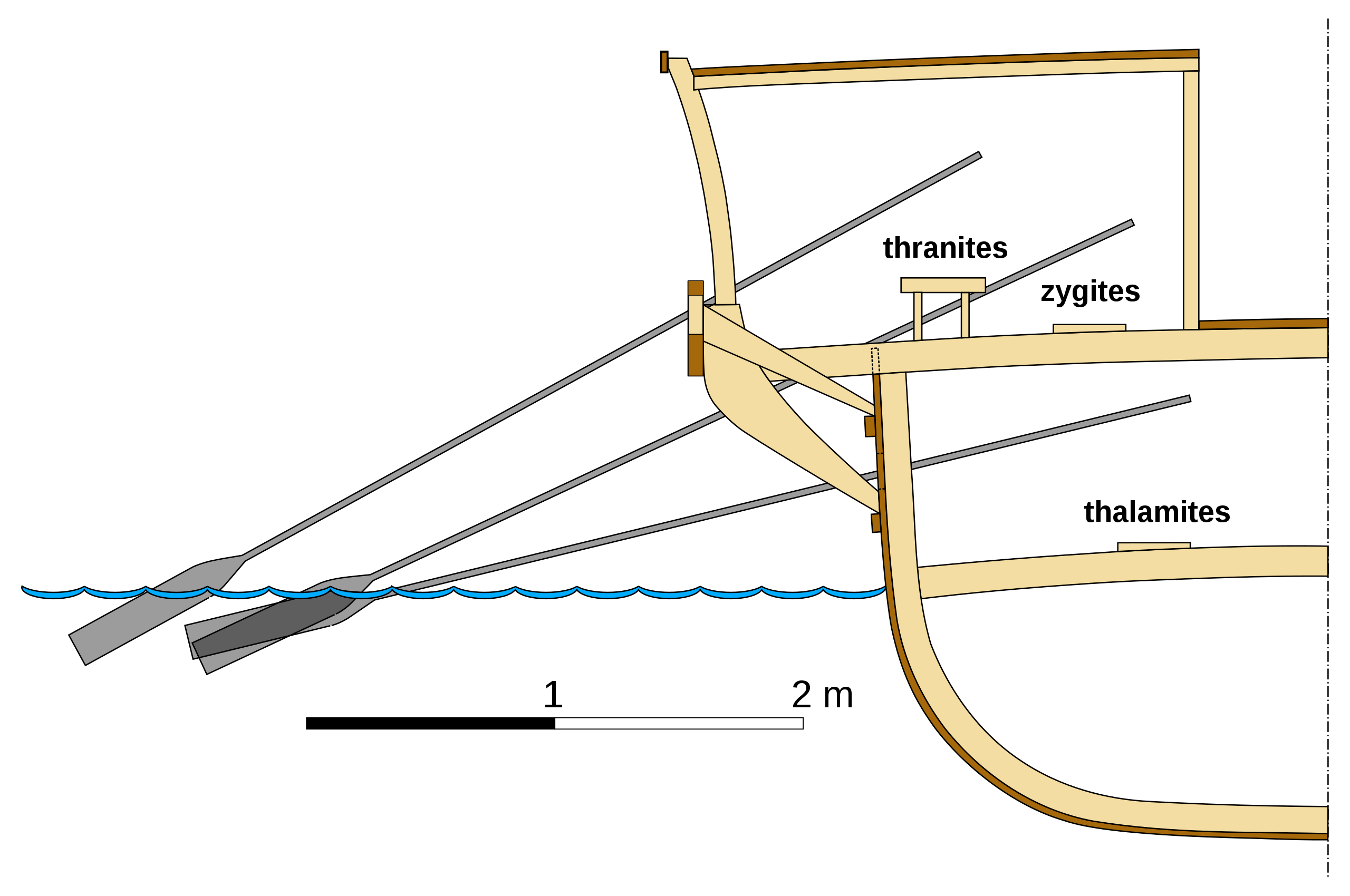

There were typically 170 oarsmen on each ship, providing the speed and power a trireme would rely on in battle, distributed across three banks of rowers. Oarsmen were usually drawn from the lower levels of society, including the poor, mercenaries, and even slaves — in the case of the latter, they could be freed if they performed well in battle. 62 rowers, known as ‘thranites’, were positioned above the hull, and probably comprised the most experienced oarsmen — they were probably paid more than the other rowers, and were the only ones who could see outside the ship during battle. Inset from them were 54 more rowers, known as ‘zygioi’, with a further 54, referred to as ‘thalamoi’, positioned below them/ The names given to the three banks of rowers were comparable to ranks, identifying where on the ship they sat to row.

Rowing a warship was a skilled job, and well-trained crews were highly valued; substantial instruction was required for new recruits to reach the required levels of performance. The physical demands of battle were significant, and it would have been easy for even experienced oarsmen to become fatigued. Seasoned and capable oarsmen could be offered extra money to lure them into further service — which was perhaps no surprise, given the better training and the skill it brought. In many ancient Greek naval battles, having oarsmen of this quality made the difference between victory and defeat.

Alongside the oarsmen would be several crew members to take care of the more technical aspects of the ship. The vessel would be commanded by a ‘trierarch,’ either the owner of the ship or (particularly in times of active warfare) an experienced individual hand-picked for the job. There was also a helmsman, a rowing master, a purser, a bow officer, a carpenter, a flute player (who would use sound to direct movement in battle), and someone to look after the sails.

In addition to the individuals responsible for keeping the vessel moving, each trireme would have a small complement of soldiers. Typically this would comprise ten soldiers known as ‘epibatai,’ or ‘naval hoplites,’ armed in the same manner as land-based infantry. They had two main jobs — to try and board the enemy ships when an opportune moment arose, and to repel attempts to board their own.

While ten epibatai were the minimum, more could be used in battles where the aim was to board as many enemy ships as possible, a tactic particularly used in confined waterscapes, with up to forty known to have been deployed per ship under such circumstances. Supporting the epibatai would be a small number of archers, usually four, who could rain down arrows on the enemy during battle. With an effective range of up to 500-550 feet, archers could try and pick off individual officers on enemy ships during battle, aiming to create chaos among the crews left behind. Despite often being limited in number, these archers played a key role in battle.

Fighting at Sea

While fleets engaged in a number of activities, from transporting troops to blockading enemy harbors and coastlines, their main purpose was fighting engagements at sea. But entering into a naval battle was a risky decision, and not one to be taken lightly. Although the gains in victory were substantial, the economic and manpower losses of defeat could be significant, too — and even victorious sides could find themselves heavily impacted by their efforts.

Crews were trained in battle maneuvers, sometimes when they were already in close proximity to the enemy. Although some naval battles took place as soon as two enemy fleets encountered each other, many occurred only after several days of preparation and strategizing. While this training may have helped with the tactical aspects of naval battle, it likely did little to prepare them for the horrific realities of fighting at sea, including the injuries that could be sustained from a direct hit to the oars or from an arrow, and abandoning ship. Crews could be reluctant to engage in battle, particularly if they had recently taken part in a defeat, and the ancient Greek historian Thucydides noted that a good fleet commander had to keep a keen eye out for ships that seemed hesitant to advance and make a special effort to ensure they followed their orders to do so.

The primary objective was to neutralize the threat offered by the opposition fleet, either by sinking/incapacitating, or boarding. Ramming played a key role in most ancient Greek naval battles, aiming to use the bronze rams fitted to the front of each trireme to rip holes in the side or rear of an enemy vessel.

Rams had been key parts of maritime weaponry before the development of the trireme. The first known naval engagement where ramming played a key tactical role was the Battle of Alalia (c. 540-535 BC), fought off the coast of Corsica between Phocaean Greeks and the Carthaginians. By the 5th century BC, it had become the predominant tactic used in naval battles.

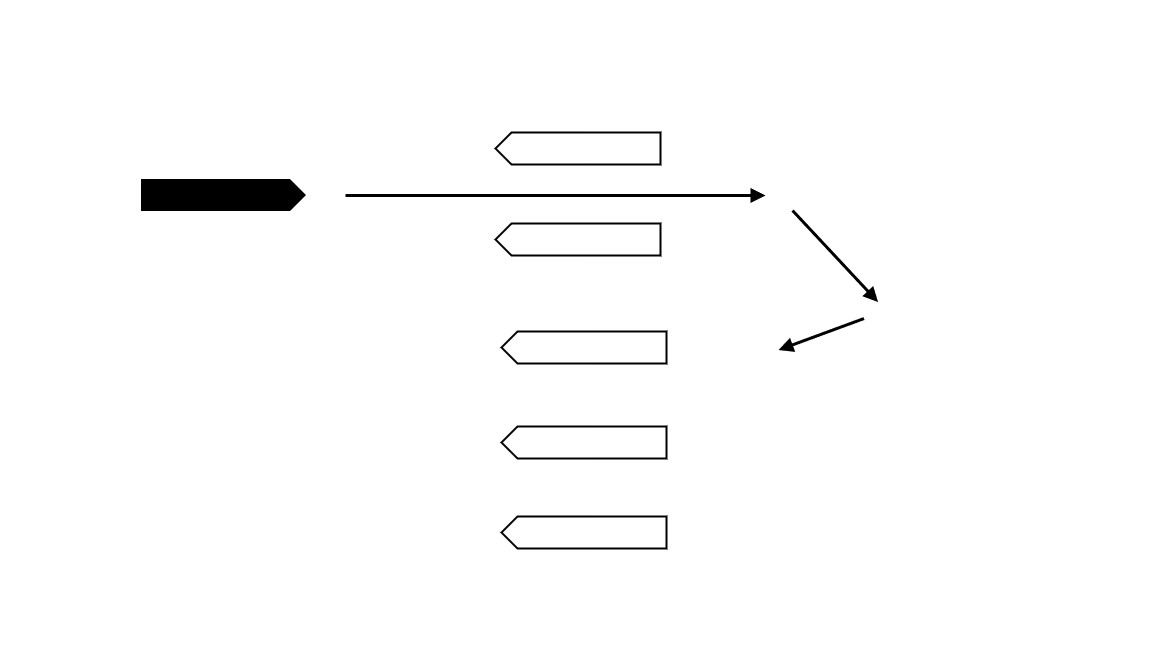

As the aim was to ram the side or rear of the ship, Greek fleets needed to get either through or around their enemy’s naval formation, and had two main methods for doing so: the ‘diekplous’ and the ‘periplous.’

The diekplous saw ships trying to break through the enemy’s line, allowing a ship to sail through the gap and attack from the rear, while the periplous saw ships try and outflank and encircle the enemy, allowing them to attack to the side and rear.

As a defensive measure against these attacks, ships could adopt a bow-out circle formation known as a ‘kyklos’ (literally ‘circle’), to prevent them from being outflanked, from which they could try and attack individual ships, while the enemy circled at speed to try and find or create gaps in the formation. Fear of being outflanked could also lead fleets to deploy with one side close to the shore, to minimize the chance of finding the enemy on both sides (and so survivors could reach safety on land if forced to abandon ship).

It did not take a vast amount of speed to penetrate a ship’s hull. Estimates suggest somewhere between four and eight knots, which would not be too difficult to achieve outside of very confined naval battlescapes — modern reenactments have suggested that even relatively relaxed rowing would produce around six knots of speed. Over time, warship design evolved to have stronger hulls with additional beams to reinforce the areas they would most likely be hit, although the response to this development was to angle rams downwards so they would hit below the strengthened area.

While ramming was highly effective in battle, it was not easy to achieve, particularly with inexperienced crews, which was one reason why trained oarsmen were highly valued. From the 3rd century BC onwards, ships could try and set the enemy’s vessels on fire during battle, not to sink them, but to create a disruption that could lead the rowers to abandon their posts — particularly if the ships began to fill with smoke — exposing the side and rear to a ram attack. Breaking the enemy’s oars could also reduce their movement capabilities and make them more vulnerable to ramming, while also causing serious, even fatal, injuries to the oarsmen manning them; something which must have been traumatic for those rowing nearby.

Although ramming was the most effective way to win a battle at sea, it was not the only method used to try and gain the upper hand. Marine soldiers could attempt to use grappling irons to get a fix on a ship, board it, and fight with the soldiers on it in an attempt to gain control — or to distract the crew for long enough for their rams to reach it. This method would often be preferred when one fleet knew it lacked the speed of their enemy’s vessels, leading them to choose brute force over rapid maneuvering and ramming, or in more confined naval battle areas where the necessary momentum would be hard to establish.

Naval Warfare in Ancient Greece

Fighting at sea played a key role in Ancient Greek warfare alongside its land-based counterpart, with most wars containing episodes of both land and maritime conflict. While most city-states maintained both land and sea forces, many were more proficient in one or the other. For instance, Sparta was known for its infantry, while rivaling Athens relied on a powerful navy.

In times of crisis from foreign invasion, the Greek city-states could ally themselves in the face of a common threat, combining the best of their infantry and marine forces. During the Second Persian Invasion of Greece (480-479 BC), the Persian advance over land was initially blocked by an army at the pass of Thermopylae, spearheaded by King Leonidas and his 300 Spartans, while a 271-ship naval force led by the Athenians assaulted the Persian fleet in Straits of Artemisium — with both conflicts taking place in the same three-day period. The Athenians had spent several years building up their navy in expectation of the invasion, and a prediction from the Oracle at Delphi had given them cause to believe their faith in the ships was justified. It told them that the “wooden wall” would not fall, which the Athenian general Themistocles assured the population, referred to the wooden hulls of the Athenian fleet – and indeed, they did not fall. After later being defeated at Salamis (sea), Plataea (land), and Mycale (sea), the Persians withdrew from Greece, never to return.

During the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), the terrestrial might of Sparta was pitched directly against the naval power of Athens. The differences in their military strength meant that the conflict was inconclusive for long periods, as Sparta embarked on large-scale but strategically ineffective invasions of Athenian territory while Athens avoided land-based battles in favor of fighting a largely defensive campaign against Spartan allies by sea. The tide turned in Sparta’s favor when a new general, Lysander, proved surprisingly adept at warfare, successfully challenging Athens’ maritime dominance — and ending it forever.

Naval engagements could be a brutal part of Ancient Greek warfare, but with the right crews, ships, and tactics, it could also be a decisive one. Large fleets with capable complements allowed Greek city-states, particularly Athens, to wield significant power in and around the Mediterranean Sea. Actually being in a naval battle was likely a brutal experience for those involved, and it is easy to imagine crews becoming reluctant to engage in the aftermath of recent defeat. Despite the defeat of Athens in the Peloponnesian War demonstrating that a strong fleet was not always enough to ensure victory, maritime power would remain a key element of warfare in the Mediterranean (and beyond) for millennia afterward.

Dr. Jo Ball is a University Teacher and Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Liverpool. Her research interests include the archaeology of Greek and Roman battle, insurgency in the Roman world, and Roman combat psychology. She has just completed her first book, The Life of Publius Quinctillius Varus: The Man Who Lost Three Legions in the Teutoburg Forest (2023, Pen & Sword Military), and has contributed several articles to The War Zone. She can often be found lurking on Twitter (@DrJEBall).

Contact the editor: oliver@thewarzone.com