Aircraft shelters with varying degrees of hardening are seeing a renaissance of sorts in response to growing drone and missile threats. China alone has built over 400 new hardened aircraft shelters across various bases in recent years, not to mention many other shelters offering lower tiers of protection. This trend is being seen in other countries like Russia, North Korea, and Iran. At the same time, a debate is now heating up between the U.S. military and Congress about the value of building new defensive infrastructure for its aircraft. Aside from a few forward locales, the United States does not invest in robust shelters for its combat aircraft, which is increasingly looking like a stark vulnerability.

This all comes as drones, in particular, have completely reshaped discussions in the United States about what is necessary to adequately defend air bases and the aircraft they host, both abroad and at home. Ukraine’s recent attacks targeting Russian Su-57 Felon next-generation fighters sitting out in the open at a major test base far from its border have only underscored this threat.

To Harden Or Not To Harden?

In May, a group of 13 Republican members of Congress penned an open letter to the heads of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy seeking information about plans for new hardened aircraft shelters and other passive defensive measures at bases across the Pacific region. John Moolenaar, the Chairman of the House’s Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, and Marco Rubio, the ranking member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, were among the letter’s signatories.

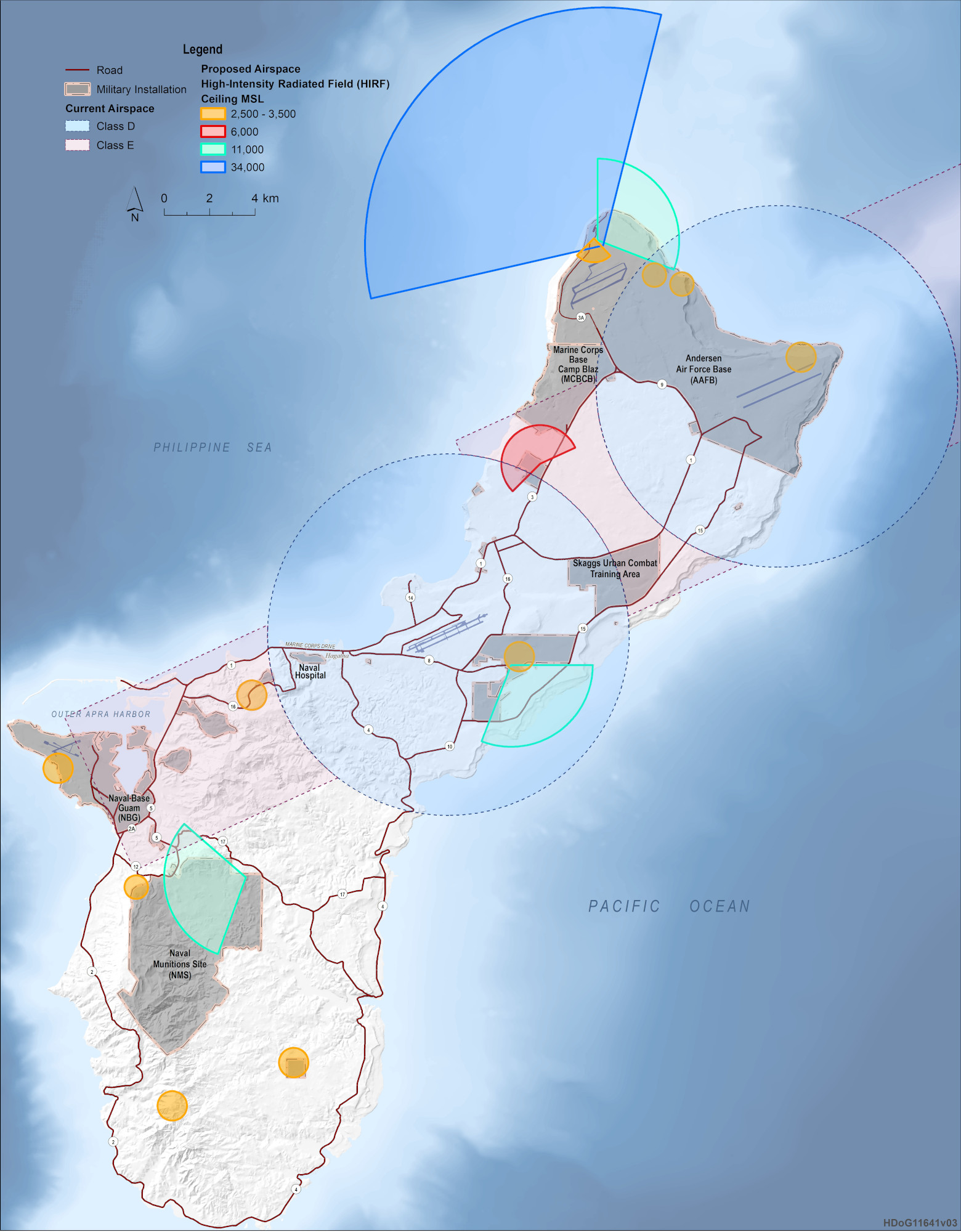

“Despite the grave threat to U.S. bases… over the last decade, it is China, not the United States, that has built more than 400 hardened aircraft shelters,” the letter noted, citing analysis from the Center for a New American Security and Hudson Institute think tanks. “During the same period, the United States built only twenty-two additional hardened shelters in the region, on U.S. bases in Japan and South Korea. Notably, there are no hardened aircraft shelters in Guam or CNMI [Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands].”

How many hardened aircraft shelters the U.S. military has in total currently is unclear. As of 2014, there were nearly 210 such structures spread across bases in the Pacific region, specifically, the majority of which were in South Korea, according to a report from Air Force Magazine. “This number reflects an almost minimal increase of 2.5 percent in [U.S.] HAS [hardened aircraft shelter] construction over the past 12 years,” that piece noted at the time.

Hardened aircraft shelters exist at U.S. air bases outside of the Pacific region, too. Much of this existing infrastructure traces its roots back to the Cold War and is in need of upgrades.

“Unsurprisingly, in recent war games [conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank] simulating a conflict with China over Taiwan, 90 percent of U.S. aircraft losses occurred on the ground, rather than from air combat,” the recent letter from the 13 members of Congress added.

An outlying U.S territory, Guam is an extremely strategic hub for U.S. military operations in the Western Pacific and, by extension, is expected to be a major target in any future high-end conflict in the region, especially one against China. The U.S. military is currently engaged in a major effort to expand the air and missile defenses on the island, which you can read more about here. Concerns about its continued vulnerability have prompted efforts to expand air base and other military infrastructure elsewhere in the region, including on Tinian in the Northern Mariana Islands.

“While ‘active defenses’ such as air and missile defense systems are an important part of base and force protection, their high cost and limited numbers mean the U.S. will not be able to deploy enough of them to fully protect our bases,” the May letter added. “In order to complement active defenses and strengthen our bases, we must invest in ‘passive defenses,’ like hardened aircraft shelters… Robust passive defenses can help minimize the damage of missile attacks by increasing our forces’ ability to withstand strikes, recover quickly, and effectively continue operations.”

“While hardened aircraft shelters do not provide complete protection from missile attacks, they do offer significantly more protection against submunitions than expedient shelters (relocatable steel shelters),” the letter’s authors conceded. The very high speeds that ballistic missiles and unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, in particular, hit in the terminal phases of their flights help penetrate deeply into hardened targets. A number of modern cruise missiles feature specialized penetrating warheads, as well.

However, hardened aircraft shelters “would also force China to use more force to destroy each aircraft, thereby increasing the resources required to attack our forces and, in turn, the survivability of our valuable air assets,” the open letter noted.

Curiously absent from the letter was any explicit mention of the ever-growing danger posed by drones, including to air bases at home and abroad, where even less robust shelters could offer important extra layers of defense. Just weeks after it was sent, Air Force officials at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in North Carolina put out a call for information about potential physical barriers that could be erected to protect F-15E Strike Eagles there from attacks involving smaller drones.

The War Zone has highlighted in the past how an adversary, even just using weaponized commercial drones, could wreak havoc on prized aircraft sitting exposed on flight lines.

The growing risk of drone attacks, even localized ones against air bases within the United States, is not idle speculation. Over a period of weeks last December, Langley Air Force Base in Virginia experienced waves of still-mysterious drone incursions, which The War Zone was the first to report. This is not the first time Langley has seen worrisome drone activity, either.

“One day last week I had two small UASs that were interfering with operations… At one base, the gate guard watched one fly over the top of the gate check, tracked it while it flew over the flight line for a little while, and then flew back out and left,” now-retired Air Force Gen. James “Mike” Holmes, then head of Air Combat Command (ACC), said back in 2017. “Imagine a world where somebody flies a couple hundred of those and flies one down the intake of my F-22s with just a small weapon on it.”

The War Zone noted at that time that jets simply parked in the open would be even easier targets and could give an adversary a way to knock out large numbers of aircraft on the ground before they would ever get a chance to get into the fight – a general scenario the letter from the members of Congress explicitly highlights.

The dangers drone attacks present extend beyond Langley and even aircraft on flight lines. The War Zone was also first to report on drone incursions over a sensitive missile defense site at Andersen Air Force Base on Guam in 2019.

These are just some of the concerning drone incidents that have occurred in recent years over or near U.S. military facilities, as well as warships offshore, along with critical civilian infrastructure, that we know about.

Multiplying Aircraft Shelters At Chinese Bases

Satellite imagery has called attention to China’s efforts to increase available aircraft shelters at bases across the country. A recent update to Google Earth’s catalog includes an image of Tuchengzi Air Base (also sometimes referred to as Dailan Tuchengzi Air Base) showing some of its relatively new fully-enclosed circular aircraft shelters. Tuchengzi, which is located in northeastern China near the Bohai Strait that links to the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea, now has 16 of these structures along a stretch of its flight line.

Construction of the shelters at Tuchengzi, each one of which is close to 200 feet in diameter, began in 2022 and work looks to have been completed early last year. The shelters were built in distinct pairs that share a wall on one side.

Work on the 11 similar, if not identical shelters at Laiyang Air Base, which lies on the opposite side of the Bohai Strait from Tuchengzi, also began in 2022 and construction there looks to have wrapped up last year. Both Tuchengzi and Laiyang are People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) facilities.

The shelters at Tuchengzi and Laiyang are sized to accommodate large airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) and maritime patrol aircraft. Pictures have previously emerged showing KJ-200 AEW&C and KQ-200 maritime patrol planes in the shelters at Laiyang. Another picture of a KJ-500 AEW&C aircraft in one of these shelters has also been circulating online, though the base where the image was taken is not entirely clear.

“The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) Naval Aviation forces have been undergoing a large scale divestment of its shore based aviation capabilities through 2023. However, since then, PLAN Aviation has clearly sought to retain not only is fixed wing anti-submarine warfare (ASW) assets, but also its other shore based special mission aircraft (SMA), notably its intelligence collection aircraft and airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) fleet of KJ-200s and KJ-500s,” a report the U.S. Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) published in September 2023 noted. “These aircraft enable the PLAN to conduct modern combined arms tasks such as ASW, supplement a currently non-operational carrier based fixed wing AEW capability, continue to collect electronics intelligence (ELINT) and signals intelligence (SIGINT), and enable further range and jointness when fulfilling air defense and domain awareness tasks.”

“Given the importance of these capabilities, the PLA has been undertaking an effort to expand the land-based facilities which support these aircraft to allow for more airframes to operate from these bases,” that same report, which mentioned the shelter work at Tuchengzi and Laiyang, added. “Since 2021, airfields supporting PLAN SMA in the Eastern Theater Command (ETC) and Northern Theater Command (NTC) have completed or started renovations of their runways or expansions of apron space to enable airfields to house more aircraft or to otherwise continue to generate sorties.”

It’s unclear exactly what level of added protection the shelters at Tuchengzi and Laiyang might provide. Even a less robust enclosed shelter design provides a layer of defense against drone attacks and shrapnel. It also complicates targeting as what is inside cannot be easily discerned by satellite. In this specific context, providing even a limited amount of extra protection for high-value, but low-density assets like KJ-500 and KJ-200 AEW&C planes and KQ-200 maritime patrol aircraft from various threats is logical. As already noted, aircraft, in general, are highly vulnerable when parked out in the open on the flight line or even under more basic shelters designed primarily to shield them from the elements.

Tuchengzi and Laiyang’s new shelters are certainly less robust than the truly hardened designs referred to in the May open letter from the members of Congress. The social media post below shows examples of fully enclosed heavily hardened aircraft shelters with heavy reinforced doors at another base in China designed around J-10 fighters. The PLA has been building fighter-sized shelters of this general type since at least 2016.

A Global Trend

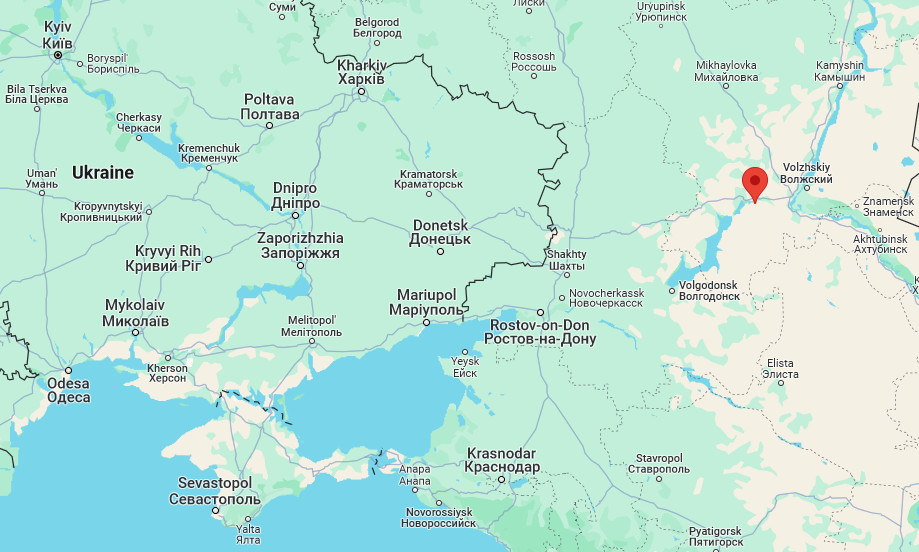

China is not the only country investing in the construction of new aircraft shelters at air bases. Another recent update to the satellite imagery available through Google Earth highlighted 12 aircraft shelters now on the flight line at Marinovka Air Base in Russia’s Volgograd region, the construction of which began in November of last year. The exact level of protection the shelters provide is unknown. Aircraft at the base continue to be seen parked in the open, as well.

The specific impetus for the erection of the shelters at Marinovka is not known, but Russian forces did claim to have downed a presumed Ukrainian drone over Volograd in September 2023. Ukraine’s widespread and daily employment of weaponized uncrewed aerial systems, including long-range kamikaze types and ones launched much closer to their targets, poses a real threat, including to aircraft exposed on aprons at air bases deep inside Russia.

There had also been some speculation that the base’s new infrastructure could be a response to Ukrainian strikes using U.S.-supplied Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) short-range ballistic missiles with cluster munition warheads. Marinovka is some 186 miles (300 kilometers) just from the Ukrainian border, which is also the maximum range of the ATACMS variants with the longest reach, and that all also only have unitary warheads. However, it is even further from the front lines and is, as such, out of range of the U.S.-supplied ballistic missiles.

What role Marinovka, which has been seen hosting swing-wing Su-24 Fencer and Su-34 Fullback combat jets, has been playing in the current conflict in Ukraine is also unclear, but the Fullbacks, in particular, have been tasked heavily in the conflict.

Russia’s armed forces certainly have already implemented new non-shelter-related defensive measures at air bases inside the country in response to Ukrainian drone and missile strikes. However, the value of having shelters available that offer protection even just against threats like smaller drones was underscored over the weekend by a new drone strike on Akhtubinsk Air Base, a major Russian aviation test facility, which targeted Su-57 Felon advanced combat jets. As has been made clear by satellite imagery The War Zone has since obtained, prized Su-57s have continued to be parked outside at Akhtubinsk despite the clear dangers of doing so.

It’s also worth noting that the Su-57 that was targeted was under a latticework for a shelter, as can be seen in the satellite image below. There is the possibility that some kind of netting was suspended on the framing, similar to what forces in the field in Ukraine often use to defend against drones, but that is not visible in the imagery. However, this seems unlikely as it would make more sense to just cover the framing completely in some way, even just to provide protection from the weather and to help prevent prying eyes from seeing what might be going on underneath.

It is worth pointing out here that Russia’s military is well aware of the threats aircraft face, including from drones, when parked in the open along airfield flight lines based on its experiences in Syria. Russian forces quickly erected shelters at the country’s Khmeimim air base outpost in that country between 2018 and 2019 expressly in the wake of repeated drone attacks, as well as ones involving the use of other indirect fire weapons. The long-range kamikaze drone strikes on the base in January 2018 were the first of their kind and provided a glimpse of what was to come, as we noted at the time.

The recent trend toward erecting new shelters at air bases, as well as pursuing other kinds of physical hardening efforts, is also visible in adversary countries with far smaller airpower fleets.

Between 2022 and 2023, North Korea built 16 new shelters at Sunchon Air Base, which is situated some 27 miles northeast of the country’s capital Pyongyang, as part of a larger expansion and improvement project. Late last year, North Korean state media released a picture showing the country’s leader Kim Jong Un, his daughter Kim Ju Ae, and other officials at Sunchon in front of the shelters with MiG-29 Fulcrum fighters parked inside them.

Last year, Iran officially unveiled a new air base, called Eagle 44, which has extremely hardened hangars and other facilities built directly underneath a mountain. This offers a level of protection far beyond even that provided by above-ground hardened aircraft shelters, but takes significant time and resources to build, as we will come back to later.

Iran has a long history now of building extensive subterranean military facilities. So do North Korea and China, the latter of which has been especially prolific in building underground military infrastructure, including to help protect aircraft at dozens of bases around the country.

Is Hardening A Waste?

The appearance of new aircraft shelters at air bases around the world in recent years is not surprising and reflects real threats that only continue to expand in scale and scope.

The danger that drones, in particular, pose to critical military and civilian infrastructure, including facilities well away from immediate conflict zones, has now fully emerged thanks in large part to the war in Ukraine. This is not a new reality, though, as The War Zone has been highlighting routinely for years now.

The steady emergence of new and improved cruise and ballistic missiles, as well as novel hypersonic weapons, are part of the equation, too. Many of these capabilities are steadily proliferating among smaller nation states and even non-state actors, as well.

At the same time, attempting to physically defend against conventionally armed ballistic and hypersonic weapons requires much more than just hardened shelters. This is typically the realm of deeply buried facilities, including ones built underneath mountains like Iran’s Eagle 44 base.

With all this in mind, in the United States, the Air Force, specifically, has signaled some support for additional base hardening efforts, and not just limited to new aircraft shelters, including the Pacific region.

“With timely investments, we can substantially improve our forward tactical air resilience,” Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said in his keynote address at the Air and Space Forces Association’s main annual symposium in 2023. “We can move forward with hardening our forward bases… without having to wait for a development program.”

At the same time, top Air Force officials have openly pushed back on the cost-effectiveness and utility of hardened aircraft shelters specifically.

“I’m not a big fan of hardening infrastructure,” Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach, then head of Pacific Air Forces, the top Air Force command for that region, also said at a roundtable at the 2023 Air and Space Forces Association symposium. “The reason is because of the advent of precision-guided weapons… you saw what we did to the Iraqi Air Force and their hardened aircraft shelters. They’re not so hard when you put a 2,000-pound bomb right through the roof.”

The Air Force has been investing heavily in capabilities to support distributed concepts of operations, as well as camouflage, concealment, and deception efforts. It is worth pointing out here that hangars and other shelters inherently make it more difficult for an opponent to see what might be inside and whether it is worth attacking. An adversary could well be forced to expend valuable munitions and other resources to destroy what could turn out to be completely empty shelters. It could also just make it harder for the enemy to keep track of friendly movements.

In their open letter this month, the 13 Republican lawmakers did acknowledge that “constructing hardened shelters for all our air assets may not be economically feasible or tactically sensible” At the same time, “the fact that the number of such shelters on U.S. bases in the [Pacific] region has barely changed over a decade is deeply troubling.”

More recently, as part of the process of drafting the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for the Fiscal Year 2025, members of the House Armed Services have also demanded a briefing from Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin specifically about efforts to harden military facilities on Guam. Among other things, legislators explicitly want to know more about the “utility of hardened structures on Guam to ensure continuity of operations and the safety of military and civilian personnel.”

The debate in the United States over how best to defend air bases, and whether to build more hardened aircraft shelters specifically, is clearly not over. In the meantime, other countries, including America’s top competitors China and Russia, are moving ahead with expanding their use of aircraft shelters offering various tiers of additional protection.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com