The Army has racked up 170 kills with Coyote counter-drone interceptors in operational deployments globally. This underscores Coyote’s centrality in the service’s arsenal of systems to help tackle growing threats posed by uncrewed aerial systems.

Army officials highlighted Coyote’s achievements at the Falcon Peak 2025, a counter-drone capabilities demonstration at Peterson Space Force Base in Colorado this week, which The War Zone and reporters from other outlets observed. The service currently has Coyotes deployed at 36 unspecified sites outside of the United States.

“So we’re in [the] CENTCOM region, AFRICOM, [and] EUCOM,” Army Maj. Alyssa Tallmadge from the service’s Program Executive Office for Missiles and Space told The War Zone‘s Howard Altman on Wednesday, referring to the top U.S. military commands in the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. “As we’re over there for Coyotse, we’re at 170 successful kills in all those regions.”

At Falcon Peak 2025, Tallmadge did not provide a more specific breakdown of kills per region or whether Coyotes have scored kills everywhere they have been deployed. The War Zone has reached out for more information.

Operational use of these interceptors, which defense contractor Raytheon produces, in the Middle East has been previously reported. Coyotes were also notably among the defensive capabilities deployed to protect a temporary pier attached to the shore of the Gaza Strip that the U.S. military briefly operated to try to help get more humanitarian aid into the enclave earlier this year.

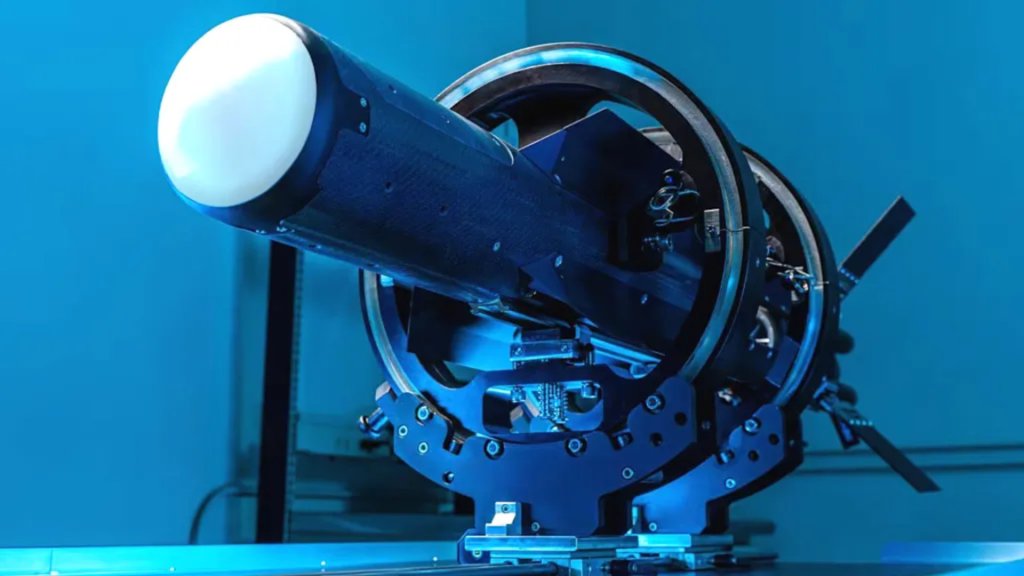

The primary versions of Coyote that the Army currently employs in the counter-drone role is the jet-powered Block 2 variant and its subtypes, which use a high-explosive warhead to destroy their targets. The service has also been looking to acquire Block 3 versions based on the original electric motor-driven pusher propeller design carrying unspecified “non-kinetic” payloads, which might include electronic warfare systems or high-power RF pulse payloads.

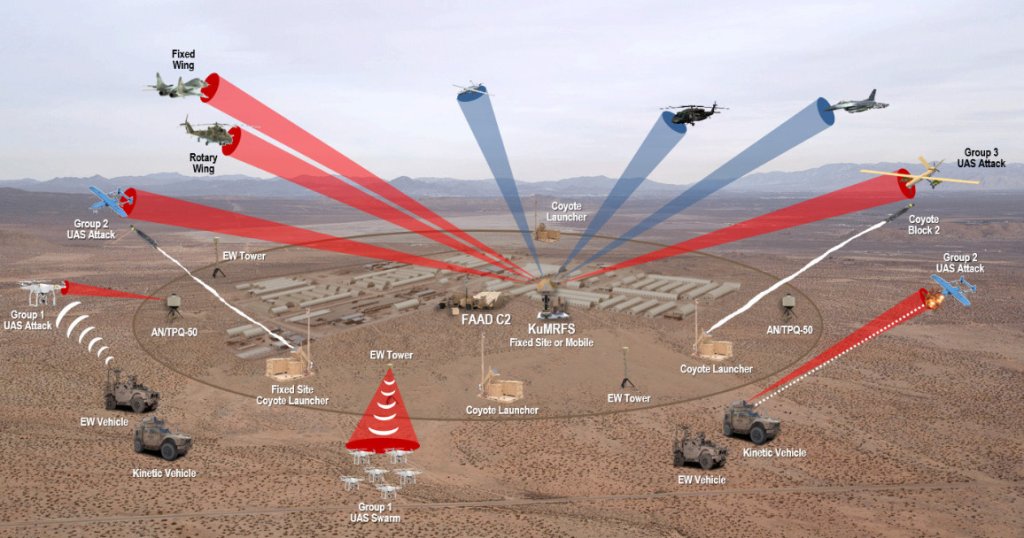

The interceptors are part of a larger system of systems in Army service collectively referred to as the Low, Slow, Unmanned Aircraft Integrated Defeat System (LIDS), which includes mobile (M-LIDS) and fixed-site (FS-LIDS) components.

The mobile end of LIDS currently includes multiple configurations of 4×4 M-ATV mine-resistant vehicles, including ones armed with Coyotes and 30mm XM914 automatic cannons, as well as radars and other sensors. The Army is now pursuing a new M-LIDS platform that consolidates all of the existing capabilities onto a single 8×8 Stryker light armored vehicle.

FS-LIDS includes palletized Coyote launchers and sensor systems that can be rapidly emplaced, including at remote and austere forward locations.

The LIDS system of systems can be integrated into larger air and missile defense ecosystems using various network architectures. The FS-LIDS components at Falcon Peak 2025 were linked to additional sensors via a Forward Area Air Defense Command and Control (FAAD C2) system and other networks during the demonstration. It’s worth noting here the Army is also in the process of fielding a new over-arching air and missile defense-focused network called Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS), which is expected to eventually subsume many existing systems like FAAD C2, as you can read more about here.

As noted earlier, it has already been clear that Coyote, together with the rest of LIDS, occupies a central place in the Army’s current counter-drone arsenal, and that this only looks set to grow in the near term. Last year, the service disclosed plans to buy as many as 6,000 Block 2 and 700 Block 3 Coyotes, as well as hundreds more launchers and radars, between Fiscal Years 2025 (which started on October 1 of this year) and 2029.

Earlier this year, the Army further announced plans to establish nine new dedicated “counter-small UAS (C-sUAS) batteries” as part of a broader force restructuring focused heavily on expanding air and missile defense capabilities and capacity. How those batteries might be equipped is unclear, but giving them combat-proven Coyote interceptors and the rest of LIDS would be obvious potential options.

At the same time, the Army has stressed the importance of taking a broader, layered approach to defeating drone threats that requires a wider array of capabilities.

“When I was at the Joint Counter-UAS Office, we… helped field some of the Coyote interceptors,” Army Lt. Gen. Sean Gainey told The War Zone and the other reporters at Falcon Peak 2025 this week. “But also we fielded directed energy type of systems [that] work very well in the counter-UAS space, anywhere from 10 kilowatt systems all the way up to 50 kilowatt systems. And we are employing those type of systems globally right now.”

Gainey is currently head of the Army’s Space and Missile Defense Command (SDMC).

It is important to point out here that Army officials have publicly acknowledged significant issues with certain counter-drone laser directed weapons that have been deployed to date. Still, the service has remained publicly very interested in this kind of capability.

“There are also low-collateral interceptors, which I was pretty excited about in that [in] my previous capacity,” Gainey continued. “And these are interceptors that would have some sort of onboard net capturing system, or streamers, or whatever, to be able to take down some of your smaller UAS. Again, part of the layer, not the sole system, to help you be able to get after several different [threat] systems.”

Limitations with drones that fire nets or streamers have emerged, as well.

Gainey also highlighted ongoing work to develop and field high power microwave directed energy weapons for counter-drone use, as well as ‘soft kill’ options, such as electronic warfare jamming.

The Army is also known to be fielding or at least exploring a variety of other counter-drone capabilities, including containerized systems that fire 70mm laser-guided rockets and gun-armed ‘robot dogs’ and other uncrewed ground platforms. The service also recently demonstrated the ability of its AH-64 Apaches to engage uncrewed aerial threats with radar-guided AGM-114L Hellfire missiles.

Loitering counter-drone interceptors are increasingly entering the picture, as well. Defense contractor Anduril just announced earlier this month that it had received major new U.S. miltiary contracts to ramp up deliveries of its jet-powered Roadrunner-M, which can also be reused if it doesn’t execute an intercept.

Regardless, “you have to have a system of systems approach, in layers, where you have the ability to not only have RF [radiofrequency electronic warfare jamming], but also sensor/detectors, and also a complement of some type of kinetic effector, to give you the ability [to respond] across a range of threats,” Lt. Gen. Gainey stressed. “Obviously, adversaries are looking for opportunities to outpace what we’re producing. So if you employ capability in a layered approach, [it] is where you see the best opportunities for success.”

It’s worth noting that Gainey’s comments here came as other U.S. military officials at Falcon Peak 2025 stressed that they are not interested, at least for now, in using kinetic effectors, such as surface-to-air interceptors or gun-based systems, or directed energy weapons to defend domestic facilities and assets against uncrewed aerial systems. This is despite a steady stream of glaringly concerning drone incidents over and around U.S. military bases, training ranges, and warships offshore, along with critical civilian infrastructure. Often confusing authorities and policies for deploying and employing anti-drone capabilities within the U.S. homeland, as well as concerns about collateral damage, have a significant impact on the current domestic counter-drone landscape. You can read more about these issues and their broader implications in other recent War Zone reporting from Falcon Peak 2025 here.

As The War Zone has highlighted many times in the past, the U.S. military continues to very much be playing catch-up to drone threats, which are not new and continue to rapidly evolve, even when it comes to protecting forces deployed down-range. The ongoing war in Ukraine, where various tiers of drones are employed on a daily basis on both sides, together with crises in and around the Red Sea and elsewhere in the Middle, have provided significant new emphasis for the already urgent need for more defensive capabilities.

In the meantime, Coyote interceptors do continue to prove their worth overseas as part of a counter-drone arsenal the Army is still working to expand capabilities.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com