It’s official: the United Kingdom, Japan, and Italy will team up to jointly develop a new stealth fighter jet. A new international coalition sees broad collaboration from all three countries under what is known as the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP). Its ultimate aim is to have a sixth-generation air platform in the air by 2035.

A British-led stealth fighter effort, dubbed Team Tempest, was originally launched in 2018, with Leonardo’s U.K.-based division being involved from the start. What has now evolved into GCAP sees Italy join the project on a national level with defense contractors Avio Aero, Elettronica, and MBDA Italia now also involved. As for Japan, it had long been seen as a potential partner, but confirmation of its involvement in GCAP heralds the most significant U.K.-Japanese defense collaboration yet and will be hoped to bring major cost-sharing benefits.

“The international partnership we have announced today with Italy and Japan aims to do just that, underlining that the security of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions are indivisible,” British Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, said today in announcing GCAP. “The next generation of combat aircraft we design will protect us and our allies around the world by harnessing the strength of our world-beating defense industry — creating jobs while saving lives.”

Sunak further noted that the program reflected a broader requirement “to stay at the cutting-edge of advancements in defense technology — outpacing and out-maneuvering those who seek to do us harm.”

Royal Navy Admiral Tony Radakin, the U.K. Chief of the Defense Staff, and Julia Longbottom, British Ambassador to Japan, both offered their own laudatory comments about the new partnership.

A report in The Times of London newspaper states that the U.K. Ministry of Defense has already committed £2 billion (around $2.5 billion at the rate of exchange at the time of writing) to the GCAP until 2025, while Italy and Japan have each pledged to match this investment.

Interestingly, the announcement from the British government is centered around the “next generation of combat air fighter jets,” rather than the broader Future Combat Air System, or FCAS, framework. As well as the Tempest manned sixth-generation fighter, FCAS includes other complementary technologies, among them ‘loyal wingman’ type drones and a new generation of air-launched weapons and sensors. The British FCAS shouldn’t be confused with a program of the same name that France, Germany, and Spain are working together that has similar aims.

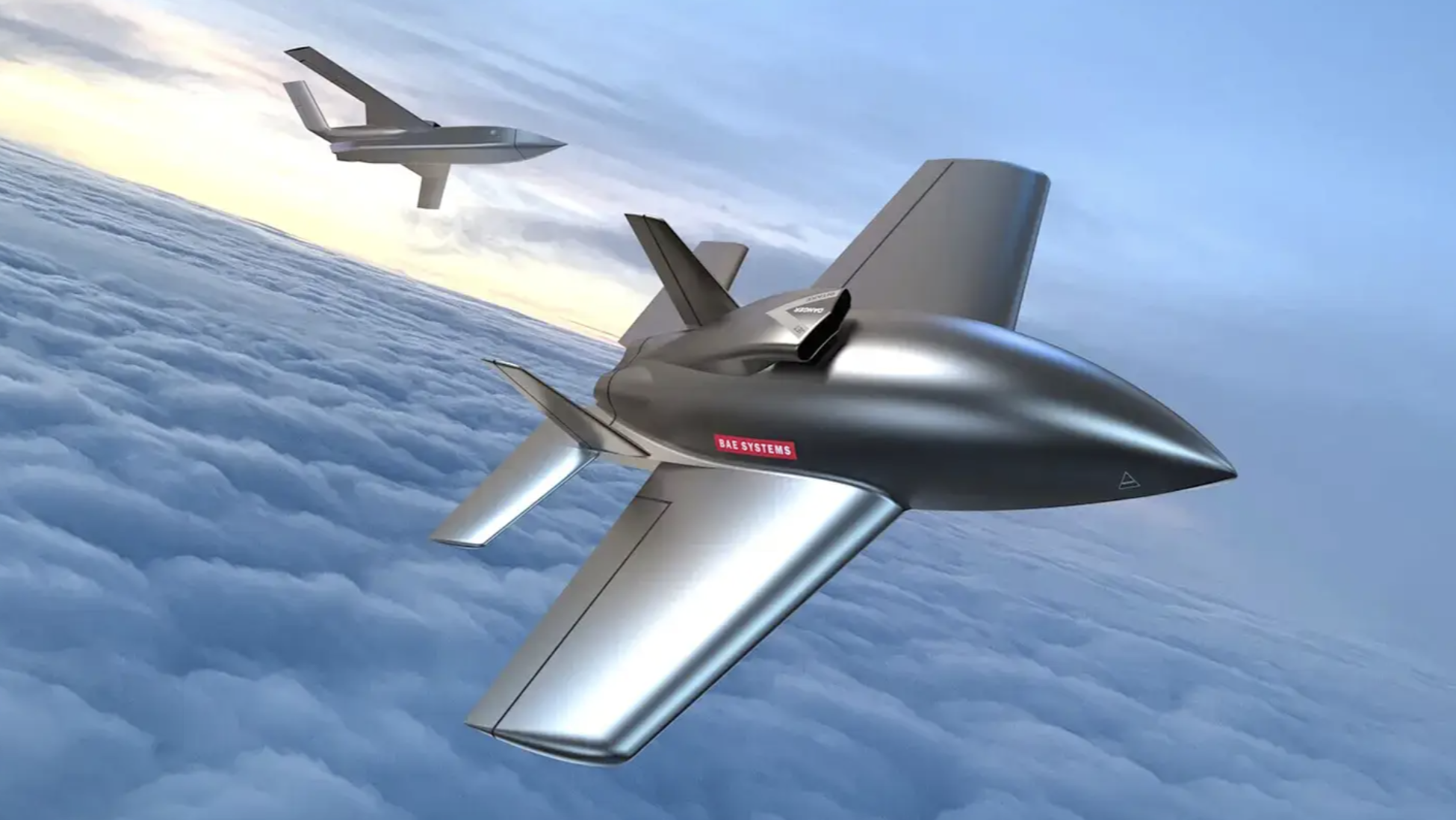

Interestingly, artwork released today along with the GCAP announcement shows fighters that share traits with the earliest Tempest concepts, as well as the modified iteration that appeared in model form earlier this year. The notional GCAP design still has the same overall stealthy configuration and moderate-to-large size. However, it has a ‘lambda’ wing seen in earlier artists’ conceptions of Tempest, rather than the cropped delta with an arrow-like trailing edge that we saw on the more recent model. The engine intakes also share much more with the earlier iterations, although the characteristic ‘pelican’ nose profile has been traded for a more F-35-style nose with prominent chine. However, these all remain concepts only, and much is likely to change before the design is finalized.

Also today, the British prime minister visited the U.K. Royal Air Force (RAF) fighter base at Coningsby, England, to look over the Typhoon fighter jets that currently provide the backbone of the country’s combat fleet. The GCAP program is now planned to replace the Typhoon, with Team Tempest now set to represent U.K. military and industrial interests in GCAP.

It’s unclear at this stage exactly how the three partner nations will divide up the workshare and costs of GCAP.

Italy’s Leonardo, via its U.K.-based subsidiary, was already involved in Team Tempest, headed up by BAE Systems of the United Kingdom. Both Leonardo and BAE are also partners in the Typhoon program. Other European entities already engaged in Tempest include the European missile consortium MBDA, British engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce, the RAF, and numerous other high-tech companies.

The Japanese part of the program will be headed up by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI). This company led Japan’s Advanced Technology Demonstrator program, which produced the X-2 fighter demonstrator, first flown in 2016. This aircraft was designed to feed into Japan’s own F-X future fighter program, which now appears to have been rolled into GCAP. Its aim is to provide a replacement for Japan’s fleet of domestically built F-16-derived F-2 fighter jets.

Japanese input will also come from Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries (IHI), which would appear to be a logical partner to work on the GCAP powerplant with Rolls-Royce. In 2021, it was announced that the United Kingdom and Japan would launch work on a joint full-scale demonstrator power system, envisaged for the Tempest.

Also relevant to GCAP is a previous agreement between the United Kingdom and Japan to collaborate on Japan’s Joint New Air-to-Air Missile program, or JNAAM. This weapon is expected to combine British expertise relating to the MBDA Meteor beyond-visual-range air-to-air missile (BVRAAM) with a Japanese-developed advanced radio frequency (RF) seeker and could well contribute to the development of future armament options for GCAP.

From the United Kingdom’s perspective, at least, bringing Italy and Japan aboard as full partners will only increase access to advanced defense technologies. In the words of the U.K. government’s statement on the launch of GCAP, the program will “harness the combined expertise and strength of our countries’ defense technology industries to push the boundaries of what has been achieved in aerospace engineering to date.”

“By combining forces with Italy and Japan on the next phase of the program, the UK will utilize their expertise, share costs, and ensure the RAF remains interoperable with our closest partners,” the same statement adds. “The project is expected to create high-skilled jobs in all three countries, strengthening our industrial base and driving innovation with benefits beyond pure military use.”

Job creation has long been billed by the British government as a central pillar of the Tempest (and now GCAP). As the country faces a major economic downturn, defense programs have already taken a hit, so the economic advantages of a big-ticket — and hugely costly — initiative such as Tempest/GCAS will need to be promoted for the taxpayer.

The U.K. government draws attention to a report by private accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers from last year, which suggests the United Kingdom “taking a core role in a combat air system” could potentially support around 21,000 jobs — most of them highly skilled. The same report projects that the program could contribute approximately £26.2bn (around $32 billion, at today’s exchange rate) to the economy by 2050.

Nevertheless, there remain big questions about the feasibility of creating a new fighter jet and supporting architecture from scratch, even with Italy and Japan now involved, to help share costs and boost demand.

In fact, the U.K. government’s statement today notes that “it is anticipated that more like-minded countries may buy into GCAP in due course or collaborate on wider capabilities — boosting UK exports.”

It’s unclear what countries might yet join GCAP, although Sweden was among the nations that had shown the most interest in the wider FCAS program. It’s noteworthy that Sweden is not mentioned as part of GCAP, and the country has adopted an altogether lower profile as regards FCAS in recent months, raising some doubts as to whether it’s still involved.

Perhaps the most realistic future partners for GCAP are one or more of those that are already involved in the rival pan-European FCAS — France, Germany, and Spain.

Earlier this month, it was reported that the two main industrial partners in the pan-European FCAS, Airbus or Germany and Dassault of France, as well as other partners, had reached an agreement on launching the next phase of that program. That should have helped resolve a long-running dispute between Airbus and Dassault over workshare and intellectual property rights.

Nevertheless, there remains the feeling in some quarters that there is still some animosity between French and German partners about the organization of the program on the industrial side. In the past, the chief of the Italian Air Force has raised the possibility of some kind of merger between the two FCAS programs, arguing that “investing huge financial resources in two equivalent programs is unthinkable.”

Like the British-led FCAS, the pan-European FCAS also includes a manned fighter jet as its centerpiece, known as the Next Generation Fighter (NGF), together with various unmanned systems and air-launched weapons.

While it appears that GCAP primarily involves bringing the Tempest fighter jet to fruition, the U.K. government’s announcement also mentions that the jet will be “enhanced by a network of capabilities such as uncrewed aircraft, advanced sensors, cutting-edge weapons, and innovative data systems.”

The U.K. government says that “alongside the development of the core future combat aircraft with Italy and Japan, the U.K. will assess our needs on any additional capabilities, for example weapons and uncrewed air vehicles.”

This suggests that, for the United Kingdom at least, some elements of FCAS will be run separately from GCAP, although it’s possible they could be ported over to the tri-national program at a later date.

As far as drones are concerned, the United Kingdom is already working on its Lightweight Affordable Novel Combat Aircraft (LANCA) program, which is studying what kinds of drones will be needed for the RAF in the future. Although Project Mosquito, which was to test a loyal wingman-type drone capable of working together semi-autonomously with manned aircraft, was canceled earlier this year, BAE unveiled concepts for two new types of unmanned aerial vehicles, either of which could potentially operate as adjuncts to a manned GCAP fighter. You can read more about those drones here.

Meanwhile, it was announced more recently that U.K. drone efforts were to be accelerated, under the Low-Cost Uncrewed Air Systems (LANCA Follow-On) program.

With the first major phase of GCAP having officially kicked off today, the three partner countries have the task of defining the parameters of the jet (the so-called “core platform concept”) as well as establishing how and where it will actually be built and how the costs will be shared.

A significant part of the development and initial production is very likely to be centered upon the United Kingdom, where BAE Systems has established a new “factory of the future” in Lancashire. This incorporates advanced 3D printing and autonomous robotics. However, Leonardo, which builds Typhoons, among other military aircraft, and MHI, may well also push for their own production lines to maintain their cutting-edge aerospace skills.

Ultimately, wherever production or final assembly takes place, GCAP seems certain to draw greatly upon expertise from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program. The United Kingdom is the only Tier 1 partner in JSF, and British industry is responsible for around 15 percent, by value, of each F-35 built. Meanwhile, the only two assembly lines of any kind for JSFs outside the United States are found in Italy and Japan: the Final Assembly and Check Out (FACO) facilities operated by Leonardo at Cameri and MHI at Nagoya.

The GCAP announcement provided by the Japanese Ministry of Defense also stresses the importance of “research and development into digital design and advanced manufacture processes,” suggesting the likelihood of synergies with the U.K. effort in these areas especially. Digital design, in particular, will likely be hoped to speed up GCAP development and drive down costs. For instance, in the United States, Northrop Grumman has touted digital engineering techniques and tools as having been key to keeping cost growth and delays in the B-21 Raider stealth bomber program to a minimum.

Interestingly, the Japanese announcement also includes a joint statement from the Japanese Ministry of Defense and the U.S. Department of Defense, confirming that the United States “supports Japan’s security and defense cooperation with like minded allies and partners, including with the United Kingdom and Italy … on the development of its next fighter aircraft.” Previously, there had been the possibility that Japan might partner with the United States on its next-generation combat aircraft, although by the summer of this year it had become clear that Tokyo was more likely to team up with the United Kingdom.

Japanese investment in GCAP — and next-generation air combat capabilities in general — is likely to be buoyed by the recent decision to increase the defense budget to two percent of GDP, roughly double what Tokyo has invested in its armed forces in the past. Previously, Japan had a de facto ban on defense exports, although these restrictions have been greatly eased in recent years. But there remains a question of how the governments involved in GCAP — Tokyo especially — would handle the introduction of other nations into the program, let alone potential sales of the jet to foreign customers.

Whatever the next steps look like, the British government projects that the new fighter jet should enter full-scale development in 2025, with a demonstrator making its first flight by 2027. The new fighter, in its definitive configuration, should then take to the air in 2035. The projection from Leonardo is even bolder, stating that the jet should be “operational” by the same date.

There is no shortage of evidence of the fact that stealth combat aircraft programs have historically involved very long development times in addition to high costs. But aside from those issues, the current GCAP timelines are highly ambitious, especially bearing in mind the delicate balancing act that will now involve the three partner countries, their respective contributions, and — by no means least — their different operational requirements.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com